A Rich & Varied Culture

The Material World of the Early South

- Fig. 1: Gown, London, England, ca. 1750 (textile);

gown remodeled ca. 1770.

Brocaded silk. Length: 52 inches (front-top of shoulder to hem).

Colonial Williamsburg, gift of Mrs. R. Keith Kane , Mrs. James H. Scott, Jr., Mrs. Timothy Childs, Mrs. N. Beverly Tucker, Jr., and Mrs. Lockhart B. McGuire (1975–340).

From the time of the earliest European explorations of North America, the continent’s southeastern region was of special interest. Navigable waterways, abundant natural resources, and vast amounts of land signaled the potential for creating new wealth “if…Colonies could be rightly settled.” 1 Once Great Britain established a permanent hold on the Atlantic coast, it became even more important to populate the southern territories as a buffer against Spanish and French incursions. As a result, hosts of British and continental European settlers and thousands of enslaved Africans came to reside in the South over the next two centuries. Some were enticed by land or freedom from religious persecution. Others sought new commercial enterprises or scientific discoveries. Slaves and deported convicts had no choice in the matter. Still, each of these diverse groups found a home in the South and left their cultural imprint on the objects they made, purchased, or commissioned. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s newest exhibition, A Rich and Varied Culture: The Material World of the Early South, explores this fulsome heritage. It is the largest and most complex exhibition of early southern material culture undertaken to date. The show encompasses the territory from Maryland to Louisiana, extends from the late seventeenth century through 1840, and employs every kind of period object, from architectural and archaeological fragments to portraits, household furnishings, costumes, tools, and machines.

As the dominant political and economic power along the South’s Atlantic seaboard, England was also the main cultural force during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Not surprisingly, the majority of free residents in the coastal plain were of English descent. However, the region was also home to substantial numbers of Scottish, Irish, German, and Welsh immigrants and their offspring, while Dutch, Swiss, and Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal made Charleston their home. Concentrated groups of French Huguenots settled in Virginia and South Carolina, and the French established a substantial presence on the Gulf Coast. African-American populations lived in nearly all parts of the region and, contrary to popular belief, Native-American communities survived in many areas. In short, the early South was a melting pot, remarkable for its cultural variety and vitality, all to be seen in the objects its peoples imported or made.

Imported goods are often bypassed in studies of this nature, but they are important sources of information because they were so often carriers of new technologies, ideas, and fashions. Early southerners imported vast quantities of manufactured goods, from fashionable clothing like the English brocaded silk gown worn by Virginian Elizabeth Dandridge (1749–1800) about 1770 (Fig. 1) to the Chinese export porcelain garniture acquired by the Drayton family of South Carolina a decade later (Fig. 2). Such goods were outward symbols of their owner’s wealth and taste, but they also reveal cultural affinities: in both cases the original users of the objects sought to follow the latest English fashions by acquiring goods that were trendy in the Mother Country.

The clearest hallmarks of cultural affinity are seen in the goods made by early southerners. Immigrant artists and artisans produced objects that echoed their own backgrounds and often those of their customers. Again and again, the prevailing English presence is seen in furniture, silver, ceramics, and paintings created in the South. A likeness of Frances Parke Custis (1709–1744) was painted in the Williamsburg vicinity about 1722 and although the artist’s name is unknown, his technique is unmistakably English (Fig. 3). Depicted in her early teens, the subject’s loosely arranged attire is likely based on engraved images of English noblewomen and may be more fanciful than accurate.

The English were but one source of British cultural influence in the South. Irish artisans occasionally left their marks as well. Although fabricated on the shores of Virginia’s Rappahannock River in the 1740s and 1750s, a number of tea tables and other forms exhibit all the hallmarks of contemporary Irish furniture (Fig. 4). The bandy cabriole legs, pointed feet, and exuberantly shaped rails on these pieces are identical to those on furniture from Dublin, Limerick, and Shannon. At least two still unidentified Irish cabinetmakers settled in or near one of the small towns on the Rappahannock and continued to make furniture in the Irish manner. Only the objects’ Virginia associations and their execution in North American woods reveal the true origin of these goods.

Scottish and Scots-Irish influences are apparent as well, most often in furniture. Scores of Scottish cabinetmakers settled in Annapolis, Maryland, Norfolk, Virginia, Charleston, South Carolina, and other coastal cities, but Scots and Scots-Irish characteristics were abundant in the southern Backcountry too. Immigrants carried these traits with them as they streamed down the Shenandoah Valley and across the mountains from southern coastal settlements. An example of their presence is visible in a boldly scaled wainscot chair that descended through the Gilmore family of Augusta (now Rockingham) County, Virginia (Fig. 5). Of Scots-Irish descent, the Gilmores settled in the valley about the middle of the eighteenth century, having come from Great Britain by way of Pennsylvania. Their chair’s maker is unknown, but the piece resembles provincial Scottish and Irish wainscot chairs of the seventeenth century in both design and construction. The Backcountry tendency to hold onto familiar traditions accounts for the production of this chair so long after the style had been abandoned in coastal centers.

Transplanted German cultures also thrived in the southern Backcountry, where some communities spoke German exclusively as late as the 1820s. Artisans in these areas made culturally distinctive and sometimes old-fashioned goods as represented by a clock case from Shenandoah County, Virginia (Fig. 6). Its bombé base, arched hood, cluster of five finials, and round case door window are typical of Dutch and German baroque aesthetics from the middle of the eighteenth century, but the Virginia case was made about 1800 when most of these details were long out of fashion. The same kind of cultural transfer is seen in the products of Germanic potters who worked at a number of Backcountry locales, including the North Carolina Piedmont. For example, several artisans in the St. Asaph’s district of Orange (now Alamance) County fabricated sugar pots and other vessels that clearly express their maker’s Germanic cultural identity (Fig. 7).

Backcountry Germans were also adept at putting their stamp on imported goods from other cultures. In 1782 an unidentified artisan of Germanic extraction covered the rim of an imported English pewter dish with an array of handsome engraved ornament (Fig. 8). Originally a plain serving vessel fabricated from an inexpensive material, the dish was utterly transformed when it was boldly decorated for Hanna Feeshel of Shepherdstown, Virginia (now West Virginia), a market town in the upper Potomac River Valley. The design of the deeply cut ornament and the technique employed to fabricate it strongly suggest the work of a gunsmith.

Religious communities also left evidence of their presence in the objects they made in many areas of the South. Several Quaker cabinetmakers from Pennsylvania moved as a group to the North Carolina Piedmont in the 1760s and continued to make the same kind of furniture they had produced at home. The Salzburgers, a group of Protestant Christians deported by the Catholic Church from modern day Austria, landed in coastal Georgia in 1734, and made furniture that would easily be mistaken for European woodwork were it not for the use of North American woods. Other illustrations of this pattern abound.

Less well-known is the broad array of goods made by enslaved men and women for their white masters. Although they accounted for a sizable portion of the southern workforce, it is frequently impossible to document the goods produced by artisans of African descent. One of the few exceptions is an armchair made in the joinery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, under the direction of John Hemings (1776–1833), an enslaved woodworker (Fig. 9). The chair is clearly based on seating furniture Jefferson saw during his travels in France, but it was made in Albemarle County, Virginia, by African hands.

|

|

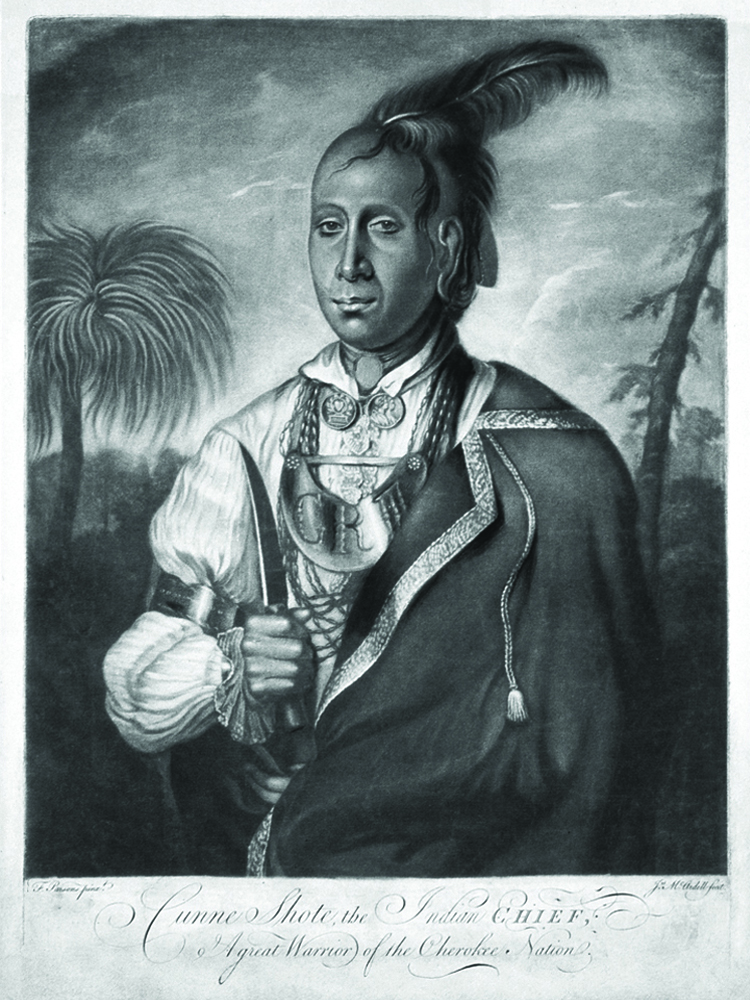

Few of the objects made by Native Americans in the early South have been identified, but the story of Native American interactions with British and European settlers is richly depicted in contemporary likenesses created by British artists. Cunne Shote, or Cummacatogue (circa 1704–1783), was one of three Cherokees escorted to London in 1762 by Henry Timberlake (1730–1765). While there, Cunne Shote sat for a portrait by Francis Parsons (active 1763–d. 1804); that image was subsequently engraved in mezzotint (Fig. 10). The subject’s combination of European and Native American clothing and accoutrements was meant to suggest harmony between the cultures. The medals Cunne Shote wore around his neck were struck in 1761 to commemorate the marriage of George III and Charlotte of Mecklenburg, while the silver gorget at his neck is marked “GR III.” The most striking aspect of the portrait, however, is Cunne Shote’s forceful grip on a scalping knife—a visual reminder of the tenuous relationship between the Cherokees and colonists living in the South.

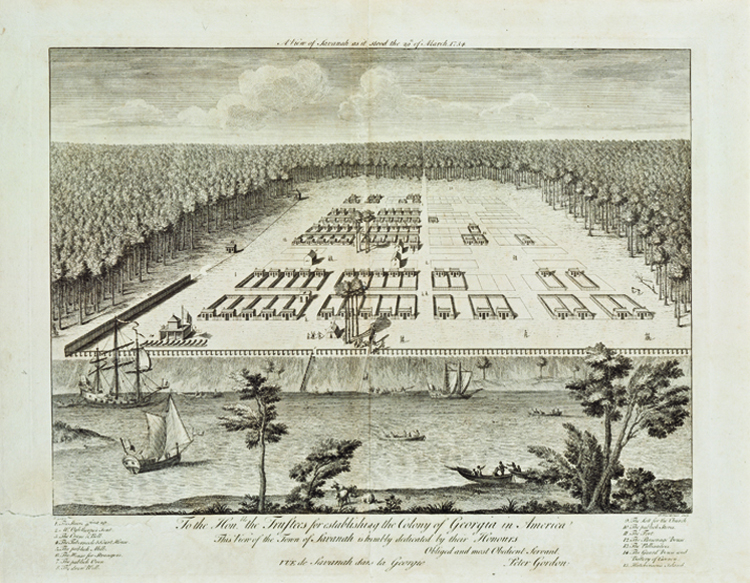

The passage of time and the dispersal of ethic groups in the early South brought many changes to the region, some of which are visible in images of the land. The early English compulsion to establish control over the landscape by rigorously surveying the terrain and cataloging every species in the natural environment is perhaps best illustrated in A View of Savannah as it stood the 29th of March 1734 (Fig. 11). Therein the town, as laid out by James Edward Oglethorpe, reflects his military background and egalitarian approach to dividing the territory. The plan presents four residential wards, each with forty house lots measuring precisely sixty by ninety feet. The extreme contrast between the limitless bounds of the frontier that stretches to the horizon and the regimented layout of the town clearly illustrates England’s desire to impose order on nature.

George Beck’s circa-1805 depiction of Boone’s Knoll on the Kentucky stands in sharp contrast to this approach (Fig.12). As southerners and other Americans strove to differentiate themselves from the Mother Country in the early nineteenth century, they embraced the ruggedness of the frontier that no longer existed in Europe. Englishman Beck painted a view of the Kentucky River that romanticized the beauty of America’s wild, open spaces. In similar fashion, while earlier generations of artisans in the American South tied their products to their own cultural roots, that pattern receded as the population moved west and southwest in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Backcountry products gradually took on a look that was more American and less European. Craftsmen developed forms and motifs in response to available natural resources and American cultural trends. For example, Tennessee potter Leonard Cain (1782–1842) produced wares that exploited the region’s orange clay (Fig. 13). His pots frequently feature striking, almost abstract manganese decoration that differs markedly from that on the products of earlier artisans along the southern coast. Likewise, a desk made in Greene County, Tennessee, offers an excellent example of the emerging American aesthetic (Fig. 14). The object’s exterior is generic in nature and minimally detailed, suggesting little about its origin, but the interior is intricately inlaid with a variety of ornaments, all grouped around an engaging interpretation of the American spread eagle.

A Rich and Varied Culture: The Material World of the Early South features more than four hundred objects either imported to or created in Maryland, Virginia, West Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Louisiana. Displayed in the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, one of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg, the five-year exhibition opens February 14, 2014. The exhibition was generously funded by a gift from Michael and Carolyn McNamara and features objects from the collections of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, Drayton Hall Plantation, Old Salem Museums and Gardens, the Charleston Museum and a number of other public and private holdings. For information call 757.229.1000 or visit www.history.org.

Ronald L. Hurst is Carlisle H. Humelsine Chief Curator and Vice President for Collections, Conservation, and Museums at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Margaret Beck Pritchard is Senior Curator and Curator of Prints, Maps, and Wallpaper at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.