The Redwood Library and Athenaeum in Newport, Rhode Island

A Classic Revisited

“Whereas Abraham Redwood, Esquire, hath generously engaged to bestow five hundred pounds sterling, to be laid out in a collection of useful books suitable for a Public Library proposed to be erected in Newport . . . and having nothing in view but the good of mankind.”

— Annals of the Redwood Library, 1891

The Redwood Library and Athenaeum is a classic: an architectural landmark, a treasury of great books, a sanctuary for scholarship, and a cultural icon (Fig. 1). As the oldest library in continuous use in the nation, it has been devoted since its inception to the art of inquiry and learning inspired by the ideals of the Enlightenment. The Doric style portico still greets visitors to the building, while within its walls await generations of Newport’s leading merchants, ministers, and men and women of letters, captured in portraits by Gilbert Stuart and others, all still watching over the institution they founded and fostered over the centuries.

Newport’s cultural flowering in the early eighteenth century laid the groundwork for the formation of the Redwood Library. Made rich from sea trade, the city became a vibrant center for the arts and crafts. Upon this scene of wealth and creativity entered the eminent philosopher, Dean George Berkeley, who arrived in 1729 with a small entourage of artists and scholars. The group only planned a short stay while awaiting funds to establish a college in Bermuda. The project never came to fruition, but Berkeley spent three productive years in Rhode Island, where he composed Alciphron, also known as The Minute Philosopher. A friend of such English literary luminaries as Joseph Addison and Alexander Pope, Berkeley added considerable prestige to Newport’s emerging intellectual life. He found fertile soil for his ideas, where freedom of thought and religious tolerance had created a cosmopolitan population from various countries and faiths, primarily Quakers, Baptists, Sephardic Jews, and Anglicans. In 1730, Berkeley joined with others to establish the Philosophical Society, devoted to “the propagation of knowledge and virtue through a free conversation.” 1 Although Berkeley returned to England in 1732, the Philosophical Society continued to thrive and evolved into the Company of the Redwood Library.

In the 1740s, the gifts of two prominent merchants gave impetus to the creation of a building to properly house the activities of the Library Company. Henry Collins, renowned as the ”Lorenzo de Medici” of Rhode Island due to his artistic discrimination and magnanimity, donated his bowling green, while Abraham Redwood matched this gesture with a gift of five hundred pounds sterling for the “purchasing of a Library of arts and sciences, whereunto the curious and impatient inquirer, after resolution of doubts, and the bewildered ignorant, might freely repair for discovery and demonstration to the one, and true knowledge and satisfaction to the other.” 2 The original collection included theological writings and works by ancient authors such as Homer, Cicero, Euclid and Pliny.3

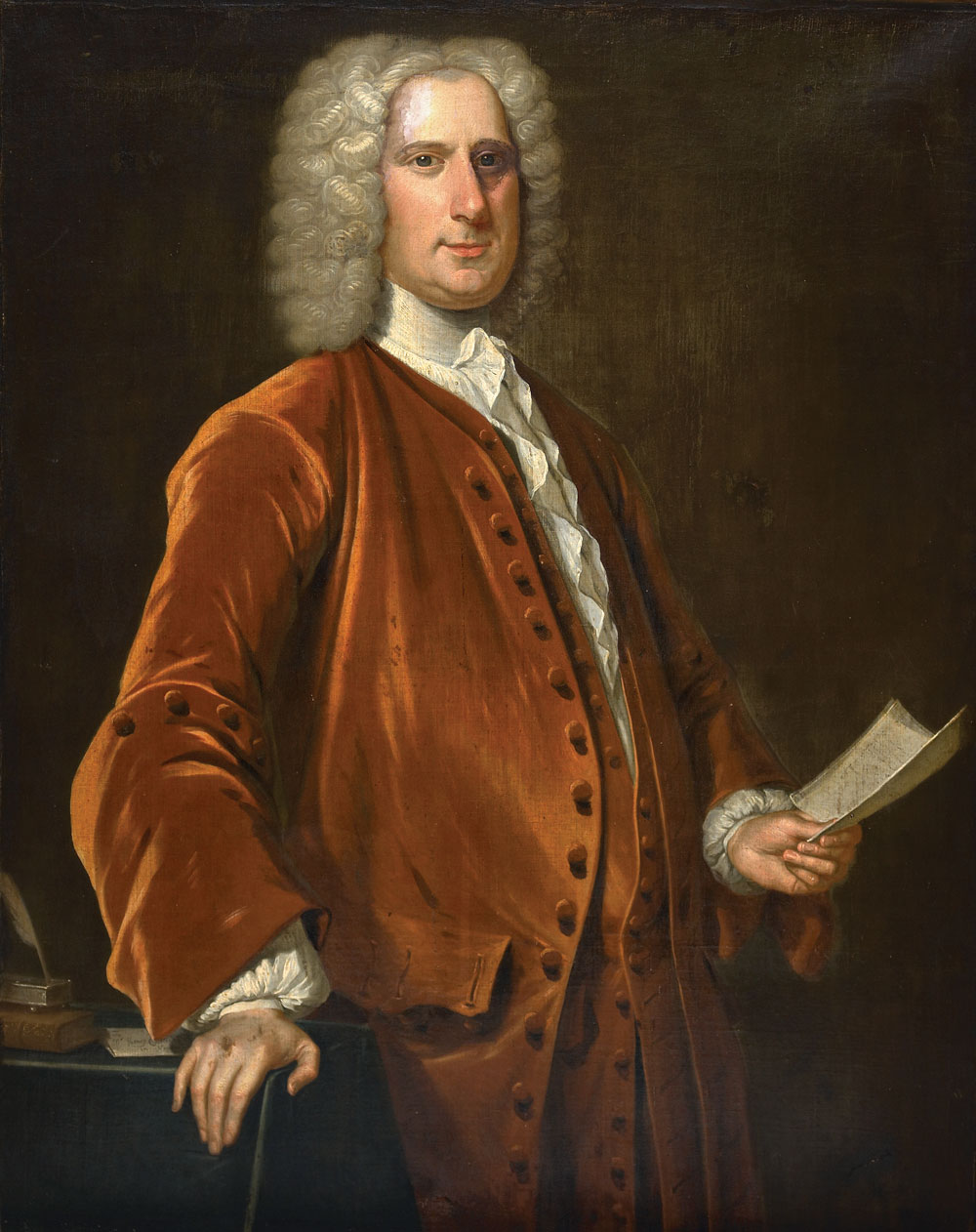

Generous benefactors, fine books, and an enthusiastic circle of thinkers set the stage for the creation of a remarkable building. In 1747, the incorporators of the Redwood Library Company engaged Peter Harrison, who designed a structure worthy of their prized volumes and appealing to their classical tastes. Born in York, England, he and his brother, Joseph, served as sea captains and merchants. They settled in Newport in 1739 and quickly rose to commercial and social prominence. In 1746, Peter married the beautiful and wealthy Elizabeth Pelham, a member of one of Newport’s prominent mercantile families. Financial independence allowed him to indulge in architecture, at that time the province of affluent and educated gentlemen.

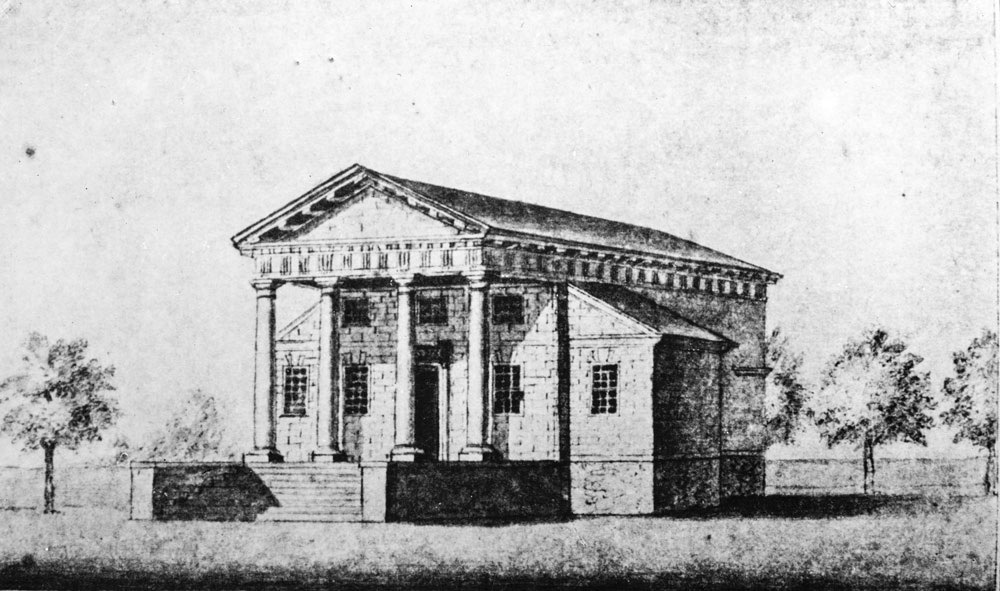

- Fig. 5: Pierre Eugene de Simitiere (1737–1784). View of the Redwood Library from the artist’s notebook (1764). Watercolor. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia. This is the earliest known image of the Redwood Library showing the original form of Peter Harrison’s building prior to later additions.

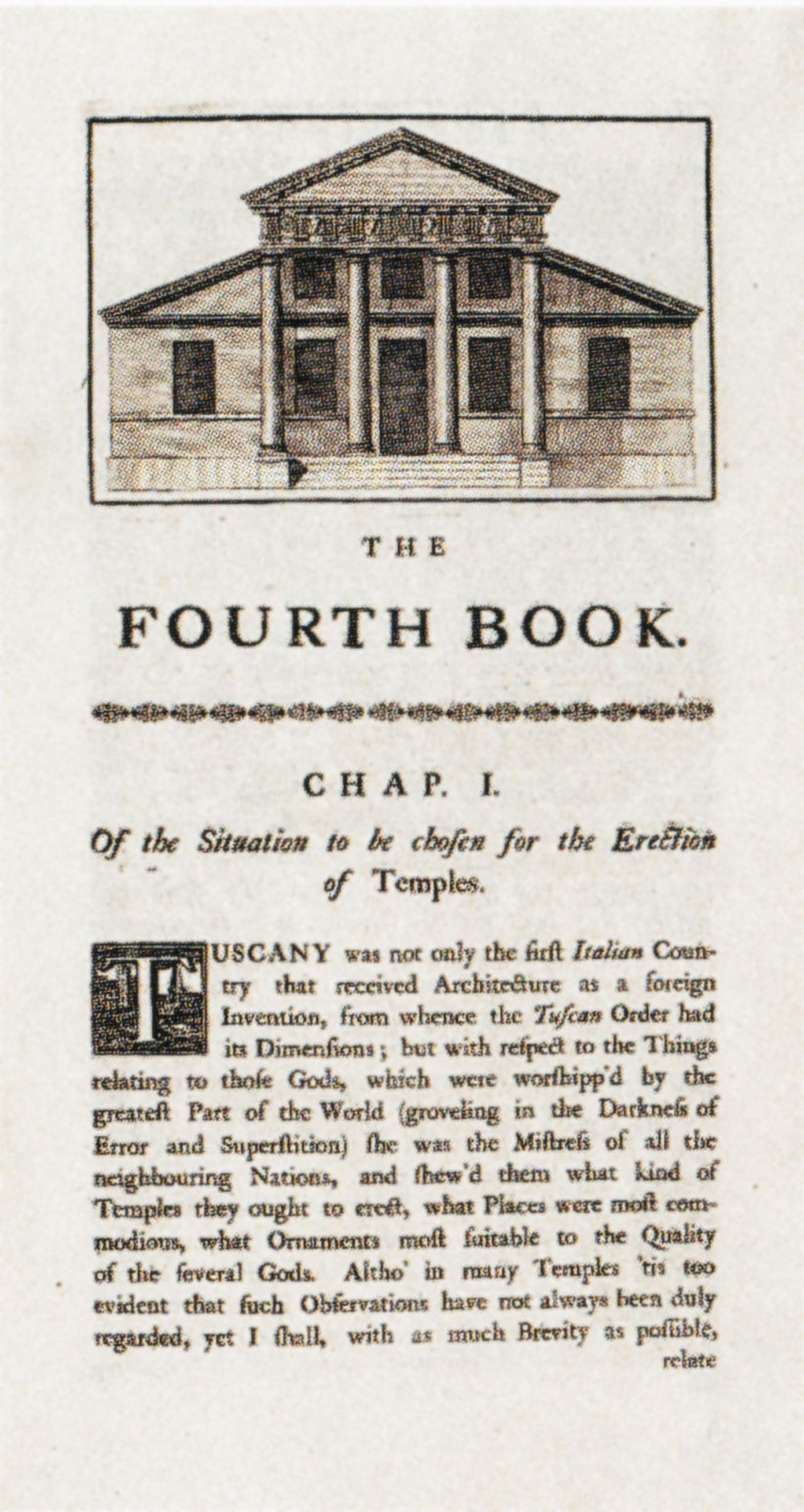

Until Harrison’s arrival in Newport, a robust baroque manner defined the city’s buildings, marked by broken pediments, bold cornices, and elaborate quoins. A Neo-Palladian order and harmony, based on the precise proportions of models in English pattern books, prevailed in Harrison’s designs and marked a new direction toward classical restraint in American building. The Redwood Library consists of a Doric portico and side wings set upon a raised foundation in the manner of a Roman temple. This scheme illustrates the masterful handling of Palladian architecture aided by a literal referencing of English and Italian models. The composition of the temple front and the creation of a plan with a large central room and two small side offices closely adheres to sources in Harrison’s extensive library: a temple front building (Fig. 2) in Book IV from the edition of Andrea Palladio’s Four Books delineated and revised by Edward Hoppus (1735); the plan and façade of a garden pavilion (Plate 43) by William Kent, featured in Isaac Ware’s Designs of Inigo Jones and Others (1740); and William Kent’s Venetian windows (Volume I, Plate 73) for Lord Burlington’s Chiswick, built in 1726; and the main elevation of the church of San Giorgio Maggiore (Fig. 3) from Some Designs of Mr. Inigo Jones (vol. 2, Plate 59, 1727).4 Both the original Palladian church designs and the English Neo-Palladian buildings in these pattern books provided Harrison with examples of elevations where a main triangular pediment is superimposed on another triangular pediment, creating a highly layered façade of strong geometric shapes precisely organized by the use of columns, moldings, and framing elements.

The construction of the library is a blend of high–minded design principles, local New England practicality, limited funding, and available building materials. Brownstone, imported from Connecticut at great expense, comprises the foundation. The structure is of wood timbers covered in pine planks rusticated to resemble stone (Fig. 4). Over the front door is a lintel supported by scrolled brackets and decorated with foliage and a scallop shell inspired by plates 55 and 73 in William Kent’s Designs of Inigo Jones.5 Fine detail and the marked contrast between light and shadow is a distinctive characteristic of the facades. The triglyphs in the cornice are crisply carved and each block of rusticated wood is carefully beveled. The building is a triumph of reason, appropriate to its educational purpose to enlighten, where every feature is clearly articulated and the spaces create a serene atmosphere. Celebrated as an architectural triumph upon its completion in 1750 and hailed as a singular building in the colonies, the Redwood Library sat proudly on a high point of ground at the edge of the city overlooking the harbor in the distance (Fig. 5). Ezra Stiles, the distinguished theologian and a founder of Brown University, served as librarian, until he became president of Yale University.

- Fig. 8: Card table attributed to John Townsend (1733–1809), ca. 1760. Mahogany. H. 26-1/2, W. 34-1/4, D. 18 in. Owned by Sarah Pope Redwood, daughter-in-law of Abraham Redwood. Presented by Ellen Townsend to the Redwood Library and Athenaeum, 1883. Photograph courtesy of the Redwood Library and Athenaeum.

This golden age of scholars and lively discussion ended when the British occupation during the Revolution left the library forlorn, albeit still standing, and much of its collection dispersed. As a Loyalist, Peter Harrison fled Newport for New Haven, where he died in 1775. With its famed architect gone and Newport no longer a thriving commercial center, the Redwood Library entered a beleaguered phase, but it aged well over time. Artists, writers, and numerous visitors, among them George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, came to see the famous site. Generations of eminent scholars and benefactors cared for the structure, reclaimed many of the original holdings, and added prints, paintings, sculpture and furniture. Pride of place is given to Gilbert Stuart’s Self Portrait (1778) (Fig. 6), and the likenesses of Newport’s powerful merchants and political figures by the leading colonial painters John Smibert (Fig. 7) and Robert Feke. Collections also include a circa-1760 card table (Fig. 8) attributed to John Townsend, and a silver tankard (Fig. 9) by Samuel Vernon, attesting to the high quality of decorative art in eighteenth-century Newport (Fig. 10).

By the mid-nineteenth century, the library had acquired the status of a monument from a heroic past. The poets Julia Ward Howe, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Emma Lazarus, and writers Edith Wharton and Henry James, who variously visited and spent summers in Newport, joined the library as members, and praised the building as a time honored treasure. As a focal point of Newport’s literati in an age of high romanticism, the Redwood Library achieved the distinction of a revered cultural icon. When expansion became a necessity, the library’s governing committees selected architects George Snell, in 1858, and George Champlin Mason, in 1875, to add reading and delivery rooms to the eastern end of the structure.6 The purity of Harrison’s original temple front on the west, facing Bellevue Avenue, was to be preserved now that it held the position of a memorial to the colonial era in one of America’s most historically intact cities (Fig. 11).

- Fig. 11: General view of the Harrison Room: Paintings from left to right: Robert Feke (1705–1750), Rev. Thomas Hiscox, 1745. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 inches. The Gladys Moore Vanderbilt Memorial Collection; Partial gift of descendants of Countess Laszlo Széchényi, 1991; Alfred Hart (1816–1908), Dean George Berkeley, 1858. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 inches. Gift of Charles H. Olmsted. Charles Bird King (1785–1862); Abraham Redwood, 1817. Oil on canvas, 42.3 x 34.3 inches. Gift of the artist, 1817; Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), John Banister, 1774–1775. Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 inches. Gift of David Melville, circa 1859; Gilbert Stuart. Self Portrait at Twenty Four, 1778, Oil on canvas, 16-3/4 x 12-1/4 inches; Gilbert Stuartm Christian Banister and Son,1774–1775. Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 inches. Gift of David Melville, ca. 1859; Gilbert Stuart. Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse ca. 1775. Oil on canvas, 22-1/4 x 18 inches. Bequest of Louisa Lee Waterhouse, 1864. Photograph courtesy of the Redwood Library and Athenaeum.

Beyond the legendary portico, fine collections, and association with famous names, the significance of the Redwood Library resides in its role as an example of the relationship between buildings and books since the structure itself arises from the pages of renowned architectural treatises. In keeping with this dialogue between design and literature, the library holds the Cary Collection of English and Continental pattern books, including the titles Peter Harrison consulted for his own projects. There are volumes on architecture and the decorative arts from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries by such masters as Jean Tijou, Juste-Aurele Meissonier, Thomas Chippendale, Robert and James Adams and Thomas Sheraton.7 In November 2015, the Cary Collection was enhanced with the acquisition of fifty-two notable publications, such as Vincenzo Scamozzi’s The Mirror of Architecture (1676). These combined treatises, books, and folios now provide a comprehensive research resource for scholars of design history in a setting infused with the air of antiquity.

Today, the Redwood Library and Athenaeum is a National Historic Landmark and has a U. S. postage stamp in its honor. A time capsule of past glories and a fully functioning modern library open to all, it remains a place of both quiet study and lively activity with reading and discussion groups, the presentation of works by new authors, music, and lectures. The old and new live easily within this ancient temple form, which continues to be visited, revisited, enhanced, and enriched in the manner of a true classic.

-----

John Tschirch is an award-winning architectural historian, photographer, and a design history blogger. His photography and blog may be found at www.johnstories.com.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Ibid., 31

3. "A Catalogue of Books Belonging to the Redwood Library in Newport, Rhode Island. A.D. 1750." Archive of the Redwood Library and Athenaeum.

4. Carl Bridenbaugh. Peter Harrison "First American Architect." (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1949), 48–49.

5. bid., 50. Harrison also designed King’s Chapel (1749–1754) in Boston, Christ Church (1759–1760) in Cambridge, Mass., Touro Synagogue (1762–1763), and the Brick Market (1762–1772) in Newport. All reflect his use of architectural pattern books and mastery of the Palladian manner.

6. In 1914, architect Norman Isham restored the main room, now known as the “Harrison Room,” removing nineteenth-century balconies and adding bookcases in a Colonial Revival style. See Norman Isham correspondence entitled Redwood Library, June 10, 1914. Collection of the Newport Historical Society.

7. Christopher P. Monkhouse and Thomas S. Michie, "Furniture in Print: Pattern Books from the Redwood Library" (Providence, RI: Rhode Island School of Design, 1989). Also, John R. Tschirch and James L. Yarnall, "Guide to Architectural Research Resources" (Newport, RI: Redwood Library and Athenaeum, 2010).