A New Approach to Furniture at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

The Dr. Susan Weber Gallery

“Fantastic objects in museums are passed by every day because people don’t have an insider’s perspective.” 1

For over one hundred and fifty years the V&A has been collecting furniture and displaying it alongside the other decorative arts in its major galleries, but until now it has never had a gallery focussed solely on furniture and how it was made.2 Moreover, the Dr. Susan Weber Gallery (Fig. 1), which opened in December 2012, is the only dedicated gallery in the world to show a comprehensive display of Western furniture from the Middle Ages to the present day. Like the V&A itself, the new gallery is intended to be a resource for designers and makers, conservators and restorers, students and collectors, but is also for anyone with a curiosity about furniture or a desire to understand how things are made.

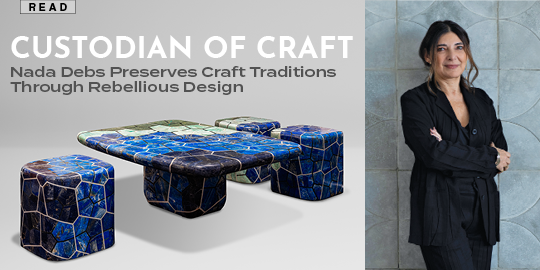

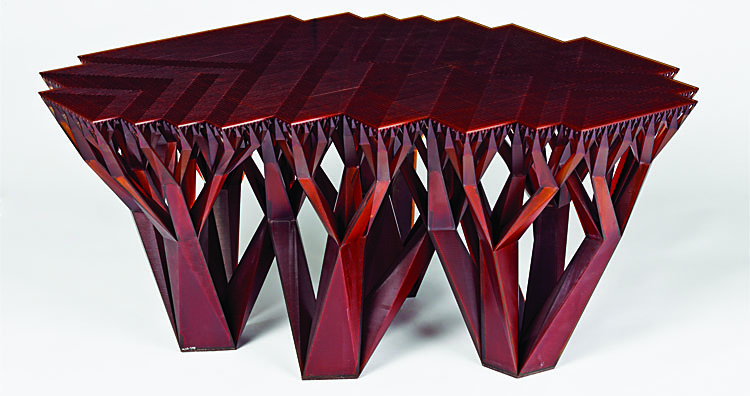

The two hundred pieces of Western furniture on display in the gallery are strikingly diverse, geographically and historically. From an English medieval book cupboard to the “Fractal” table (Fig. 2) made using the latest digital 3D printing technology; from an Italian sixteenth-century sgabello chair to Breuer’s Bauhaus tubular steel armchair; from a gilded rococo mirror with papier-maché branches to an inflatable plastic chair. The frequency and boldness of color and specialist finishes will surprise those used to thinking of historic furniture as uniformly dull brown. Occasionally, an Asian or pre-medieval piece offer a different perspective on familiar Western techniques by showing, for example, urushi lacquer, Islamic intarsia, or ancient Egyptian wood turning. (The absence of beds, omitted owing to their size, complexity and reliance on textile hangings, was mitigated by the four major examples already displayed in the British galleries directly underneath the new space.)

The driving principle of the new gallery is that understanding how furniture is made transforms our understanding of furniture design. To enhance understanding and to make the gallery accessible in different ways, there are three types of displays. Along the spine of the gallery, a chronology of twenty-five key pieces introduces the principal forms of Western furniture. Since the gallery has doors at both ends, this parade can be read as an “evolution,” or, looking backwards, as an archaeological exploration, uncovering the layers of ancestor furniture cultures. The pieces are shown in the round so that their backs are deliberately, sometimes shockingly exposed, revealing, for example, the roughly nailed backboards on an Irish bureau (1730–1740) said to have belonged to the satirist Jonathan Swift, and the superb joinery behind Edwin Lutyens’ stupendous circa-1905 safe cabinet (Fig. 3) for Marsh Court. The high plinths used in the gallery, closer to bench height than to floor level, also encourage a glimpse of the steel armature Lutyens concealed within the stand to support the great weight of a fireproof safe. It’s a telling example of the interrelatedness of function, design, and construction in furniture.

Along the recessed sides of the gallery are sixteen making displays that address techniques by which furniture is constructed (such as joinery and cabinet-making, bending solid materials or casting liquids, cutting sheet material or digital manufacture); decorated (such as marquetry [Fig.4], gilding, and lacquer); or used to construct as well as to decorate (such as carving or turning). A large, glazed display presents a sumptuous array of original seat upholstery along with alternative approaches to comfort such as cane or rush. A range of devices in front of each display offer insights into craftsmanship: a short film shows the making of the Panton cantilevered plastic chair by injection moulding; a series of replicas shows the creation, stage by stage, of eighteenth_century pictorial marquetry in its original, brilliant colors; cutaway diagrams reveal the structure of upholstery or joints that are normally hidden.

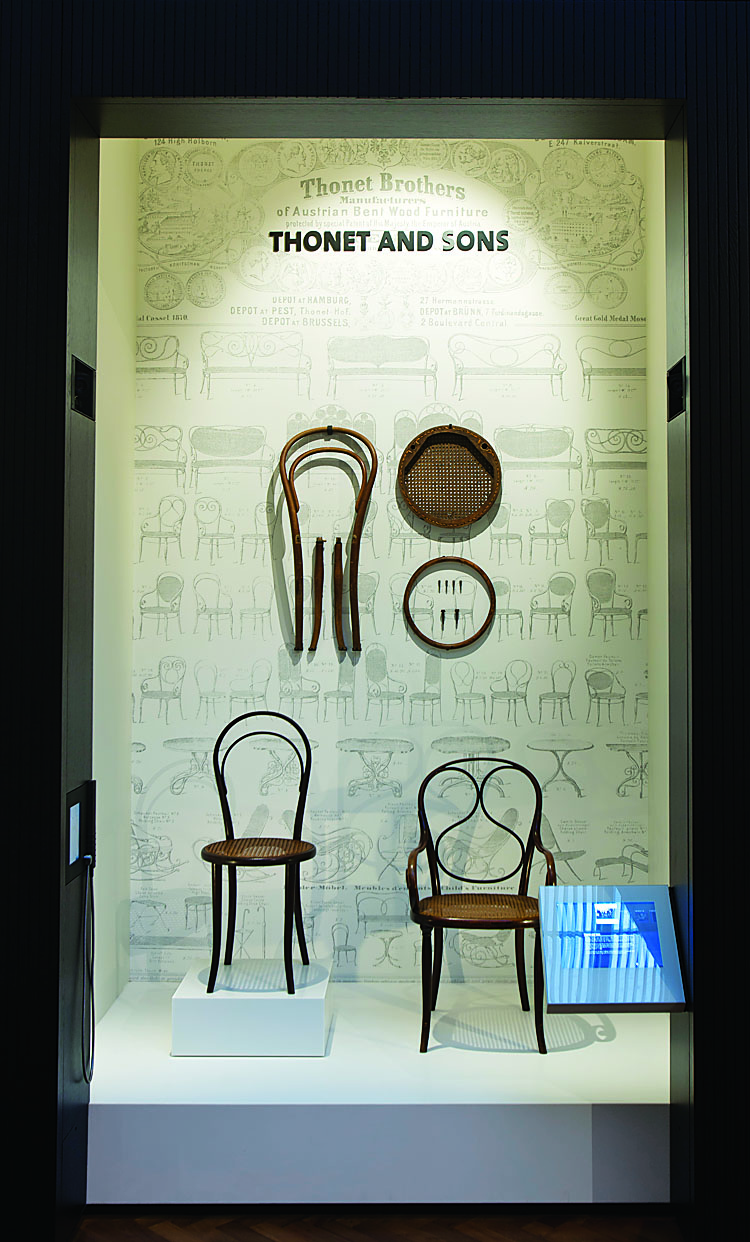

Punctuating the making displays, smaller portals address the careers of eight named designers, including Thomas Chippendale, Michael Thonet (Fig. 5), Frank Lloyd Wright, and the Orkney chair maker David Kirkness, whose workshop exported thousands of straw-back chairs before and after 1900. Whereas so much pre-1900 furniture is anonymous, these offer a personified perspective on the history of furniture making, by considering the particular skills of the makers, and showing how their ideas developed, were realized, and marketed. In short recordings, also available online, curators and contemporary designers or makers offer their personal responses to the furniture.

The creation of the furniture gallery was a long held V&A ambition, made possible by the V&A’s Future Plan, a large-scale rationalising and modernising project now entering its second decade.3 The redisplay of its top floor ceramic galleries in 2009–2010 allowed the new gallery to be redeveloped as a furniture gallery, dovetailing perfectly with the readiness of Dr, Susan Weber to sponsor the gallery. Over several years curators conducted a survey of several thousand pieces in store, assessing the importance and condition of each piece, and rating it as an exemplar of specific techniques. This review was fundamental in defining the chosen categories. It was essential that conservators and object scientists were closely involved so as to plan treatments, but more fundamentally, to analyse the materials and techniques employed. The survey also brought to light numerous pieces such as a standing trunk, possibly German, circa 1600 (Fig. 6). Its pristine appearance (still glimpsed in protected areas) must have been almost kaleidoscopic, with multicolored velvet set off against gleaming brass on bright, burgundy leather. Now muted, it offers a highly instructive benchmark of the effects of time and wear on organic materials. The gallery’s innovative digital labels show a putative reconstruction of its original appearance.

In 2010 work began with NORD Architecture, the gallery designers, to realize the environmental brief and to plan the layout. The gallery is a single long, narrow space with glazed roof that has been compared, variously, with an Elizabethan long gallery, the nave of a church, and a guildhall. The transition from concept to a designed space meant reducing the object list greatly, and thinking hard about each display so as to explain many things well rather than all things slightly. For each technique explored, a range of furniture forms made in different periods, centers, and styles was chosen. Two of the most striking aspects of furniture revealed by this approach are its diversity in appearance and the continuity in basic techniques over long periods, albeit with ingenious refinements. Unexpected and revelatory juxtapositions are frequent: a Windsor chair (1830–1850) beside Hans Luckhardt’s cantilevered tubular steel chair (1929–1930) in the display “Moulding Solids”; a commode by BVRB (1760–1765) beside Eileen Gray’s Art Deco screen (about 1928) in “Lacquer”; a north Italian chest (1460–1480) and an Indo-Portuguese table (1650–1700), both with geometric inlay, in “Veneering, Marquetry and Inlay.” Sometimes the combinations suggest surprising and complex continuities across wide distances of time and space. At one end of the chronological spine is a late sixteenth-century Augsburg marquetry cabinet (Fig.7), at the other, Eugene Berman’s 1939 surrealist wardrobe (Fig. 8). We might imagine they have little in common until we notice that both are covered in depictions of architectural ruins.

One of the gallery themes that emerges vividly is that furniture changes over time, physically as well in use and context. The likelihood that furniture has been repaired, “improved” or otherwise modified during its lifetime is so familiar as to be unremarkable, yet museums have struggled to convey this complexity. Rare, pristine pieces are, of course, fundamentally important, but we omit half the story if we disparage furniture that has been modified. The mahogany cupboard made for Croome Court, Worcestershire, based on a 1764–1766 design by Robert Adam (1728–1792), and with masterful applied carving by Sefferin Alken (1717–1782), is not the original one made for the 6th Earl of Coventry by John Cobb (ca. 1710–1778), but is, in fact, one of two smaller cupboards adapted from it in Cobb’s workshop in 1767, shortly after the construction of the original (Fig. 9).

The gallery also provides an ideal context to display fragmentary, stripped, or damaged furniture that was acquired, sometimes decades ago, for teaching purposes. Such pieces are generally deemed unsuitable for galleries that present an ensemble of glamorous works to convey stories of style or cultural authority. The joinery and cabinet-making display includes an armchair frame (1735–1740) from Richmond House that was acquired in 1975, already stripped (Fig. 10). The frame reveals the structure, later repairs, and the varied quality of carving normally concealed under gesso and gilding. The digital label highlights constructional details like the scarf joint used to reinforce the back uprights, and illustrates another, fully gilded and upholstered chair from the same suite.

By revealing aspects normally hidden, or drawing attention to the many methods and shortcuts by which makers simulated more expensive finishes, the gallery emphasizes two related themes in construction and decoration: frugality and ingenuity. Why lavish decoration or costly materials where they would not be seen? Why go to the trouble of obtaining the expensive real thing (pietre-dure, tropical hardwood, turtle-shell, solid gold) when you can simulate it convincingly with scagliola, graining, japanning or gilding? Batch production was established in furniture making long before the industrialized methods developed, for example, by Michael Thonet and his sons in the 1850s for his bentwood chairs. Consider the standardized frame and panel construction made by joiners, the use of wooden moulds to create composition ornament, or the division of labour to create Windsor chairs in eighteenth-century England, with separate craftsmen supplying stocks of turned beech legs, adzed elm seats, and bent yew bows. In a museum it is not easy to convey how such practices were applied in a busy workshop environment. However, by revealing the processes involved in cutting a mortise and tenon joint, taking plaster casts from a carved mould, or turning an ash spindle on a lathe, makes it much simpler to imagine workshops of craftsmen (and women) producing the large quantities of furniture documented by economic historians.

The gallery tries to answer many questions, and will undoubtedly raise more. How far were the choices of furniture makers prescribed by their training, the availability of materials, or the expectations (and purses) of customers? How did the various furniture trades interrelate on a practical basis? At the center of the gallery are two specially commissioned—and unconventional—pieces of furniture, which may illuminate these questions (Fig. 11). Two digital tables present clustered samples of materials used in furniture manufacture: various hardwoods and softwoods, metals, plastics and organic materials such as cane, rush, and turtle shell. When a sample is touched, the tabletop screen shows the sourcing and conversion of the material, its properties for furniture making, and key examples in the gallery. The other, Chair Bench, a seating installation by contemporary designer Gitta Gschwendtner, combines aspects of a park bench, a parlor game, and a design handbook with wit and elegance. Like the gallery, it draws together very different furniture designs and invites a second look at their construction and decoration.

Nick Humphrey is a curator in the Furniture, Textiles and Fashion Deptartment, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

All images courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum.

2. For a history of the V&A’s collecting of furniture see Christopher Wilk (ed.), Western Furniture: 1350 to the Present Day (London: V&A Museum, 1996), 9–24.

3. For a full list of the projects completed as part of FuturePlan see the V&A website: www.vam.ac.uk.