A Passion for American Art: Selections from the Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection

| |

Carolyn and Peter Lynch, Boston Public Garden in 2005. |

Carolyn and Peter Lynch shared an extraordinary life together, traveling widely and exploring American art and culture for almost half a century. Peter is best known for heading the Fidelity Magellan Fund, the best performing mutual fund in the world. With his late wife Carolyn, he established the Lynch Foundation which supports numerous educational and philanthropic endeavors. In their personal life, they were active in the groundswell of collecting American art that followed the United States Bicentennial in 1976. Highlights of their diverse collection are currently featured in an exhibition at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts.

A love of people, nature, and the places they have called home in Massachusetts and Arizona were the primary catalysts for their collecting. They also embraced architecture and design as influential factors in experiencing art in domestic settings. Freely integrating subjects, time frames, and media, the Lynches created lively, often unexpected, opportunities to explore the country’s artistic creativity, regional styles, and evolving traditions.

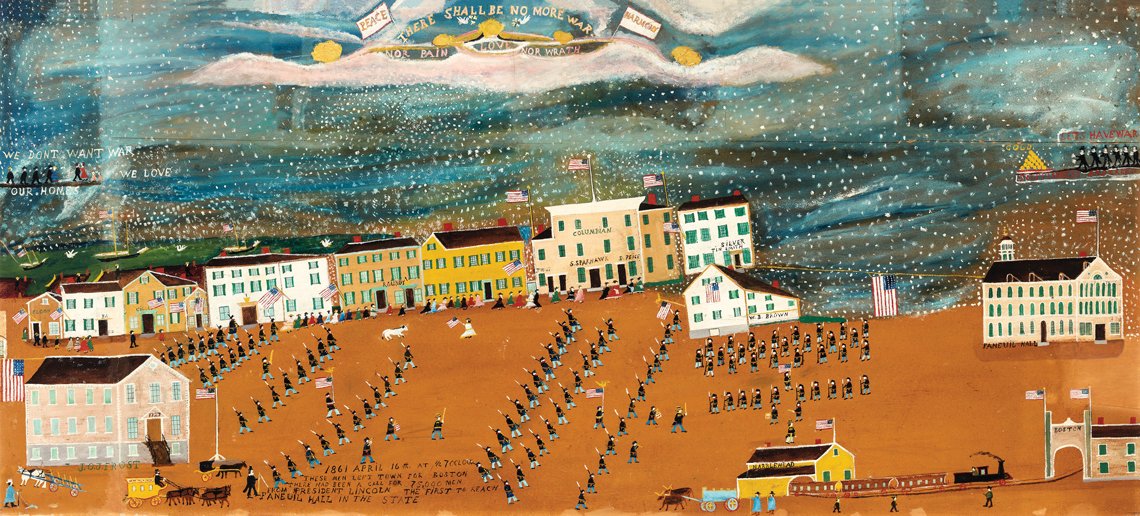

The exhibition honors the life of Carolyn Lynch, who passed away in 2015, and her long devotion to PEM serving as a trustee, overseer, and founding chair of the American Decorative Art Visiting Committee. To honor her memory, Peter Lynch and his family generously gave the museum three paintings included in this show: Childe Hassam’s East Headland, Appledore, Isles of Shoals; J.O.J. Frost’s The March into Boston from Marblehead, April 16, 1861: There Shall Be No More War; and Georgia O’Keeffe’s Cedar and Red Maple, Lake George.

The exhibition features outstanding examples of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century American furniture made primarily in Philadelphia, New York, and the Boston region, as well as rural New England towns. Each piece reflects the cabinetmaker’s desire to mine familiar traditions and the latest styles and forms from Europe, while also striving to express the new country’s ideals, beliefs, and local tastes. A selection of accompanying American paintings dating primarily from the second half of the nineteenth century reveals the Lynches preference for artists who focused on capturing human interaction with the land and sea, including William Bradford, Robert Salmon, and Thomas Chambers. Other works by Martin Johnson Heade, Frederick Carl Frieseke, and John Singer Sargent reflect the rapidly evolving sophistication of American art as artists traveled in Europe and South America to find new sources of inspiration.

Works dating primarily from the twentieth century, include Native American artists such as Lonnie Vigil and Tony Da, along with furniture makers Sam Maloof and George Nakashima, and ceramists Gertrude and Otto Natzler, all of whom departed from or reinterpreted traditions while they experimented with forms, materials, and techniques. Together these works by both historical and modern artists celebrate the dynamic nature of art in America through the course of three centuries.

|

|

J.O.J. Frost (1852–1928), The March into Boston from Marblehead, April 16, 1861: There Shall Be No More War, ca. 1925. Oil on fiberboard, 31½ x 72 inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Gift of Peter S. Lynch in memory of Carolyn Lynch (2018.72.2). |

J.O.J. Frost today enjoys a national reputation as a highly original self-taught artist and visual storyteller. At age seventy, following his wife’s death, he began painting and working with found materials to document the history of Marblehead, Massachusetts. This panoramic painting captures Frost’s childhood memory of watching his father and other Marblehead men depart on foot to Faneuil Hall in Boston to enlist in the Civil War. Following the Battle of Fort Sumter earlier that month, President Abraham Lincoln had called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion in the South. Frost’s father died during the war, prompting his son, nearly sixty-five years, later to paint this commemorative scene, which includes the words, “There shall be no more war, nor pain, nor wrath.”

|

|

Childe Hassam (1859–1935) East Headland, Appledore, Isles of Shoals, 1911. Oil on canvas, 30 x 36 inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Gift of Peter S. Lynch in memory of Carolyn Lynch (2018.72.1). |

Childe Hassam embraced the freestyle brushwork and bright color palettes of French impressionist painters before his American contemporaries. Although this celebrated artist traveled extensively, he found his muse on Appledore Island, the largest of the Isles of Shoals, off the New Hampshire–Maine coast. For three decades, he made the island his summer retreat, wandering the terrain and painting outdoors. Hassam expertly translated recognizable geological and marine features into colors and brushstrokes, capturing the textures and light effects on rock and water.

|

|

Fitz Henry Lane (1804–1865) View of Gloucester Harbor, 1858. Oil on canvas, 18 x 30 inches. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

Trained as a lithographer, Lane favored geographic accuracy in his early seacoast paintings. This midcareer work expresses his interest in abandoning strict accuracy for artistic effect. Harbor Cove, in Gloucester, Massachusetts, was a vista he revisited often for local customers. Captured in the days of the waning fish trade, the only structures Lane clearly articulated within the Gloucester townscape are the Gothic tower of the Unitarian Church and the taller spire of Trinity Congregationalist Church, neither of which survives today.

|

|

Pair of card tables, 1760–80, New York. Mahogany. H. 28, W. 35½, D. 18½ in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

Originally owned by the successful Manhattan dry goods merchant James W. Beekman, this pair of card tables is among the most sophisticated examples of eighteenth-century New York rococo furniture. The fine carving on the knees of the front legs incorporates asymmetrical C-scrolls with acanthus leaves. The unidentified maker has created a powerful sense of movement using the S-curve for the shape of the shallow skirt and elegant legs with finely carved ball-and-claw feet.

|

William Savery (1721–1787), High chest of drawers, Philadelphia, 1762–1775. Mahogany. H. 96, W. 45½, D. 24 in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. Quaker cabinetmaker William Savery created simple, well-built furniture to grace the private spaces of some of Philadelphia’s grandest homes. This labeled chest is one of the only pieces by him to incorporate carved ornament. Influenced by designs published in Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754) and the work of London trained cabinetmakers working in Philadelphia, Savery added a modest amount of carving along the edge of the front skirt and on the knees of the front legs. The impressive pediment with fine latticework and scrolls ending with swirls of acanthus leaves stands in contrast to the otherwise plain body of the chest. |  |

|

|

Shop of Nathaniel Gould (1758–1783), Stand table, Salem, Mass., 1761–1781. Mahogany and birch. H. 27½, Diam. 33¼ in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

Gould was the most important furniture maker active in Salem during the mid-eighteenth century and this is an outstanding example of his considerable skills. It is the only known Salem tea table with a scalloped edge (most often associated with work from Philadelphia), ideal for keeping tea paraphernalia—cups, saucers, and plates from sliding off. The hinged top was designed to flip up so the table could be tucked into a corner of the room. In this position, the expensive, dense-grained mahogany and finely carved details announced the owner’s wealth and good taste.

|

|

Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904), Orchid and Hummingbirds near a Mountain Lake, ca. 1875–1890. Oil on canvas, 153⁄16 x 20½ inches. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

For more than a decade, Heade painted hummingbirds in their natural landscape in South and Central America. During his final trip to the tropics in 1871, he hit upon a dazzling new combination. He began a series of compositions in which he paired the small, colorful hummingbirds with sensuous orchids. These lush, jewel-like images captivated the American art market. Though he worked directly from nature, he often reused details. The orchid here appears in twenty-one of over fifty related works he produced.

|

|

Anna Hyatt Huntington (1876–1973), Yawning Tiger, ca. 1917. Bronze, H. 8½, L. 28, W. 4½ in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

Anna Hyatt Huntington’s love of animals and keen powers of observation are evident in her poignantly accurate portrayals of animal behavior. In this elegantly streamlined composition, she creates visual tension by contrasting the simple act of yawning and stretching with the tiger’s powerful muscles and sharp teeth.

|

|

Sam Maloof (1916–2009), Low-back settee, 1989. Fiddleback (striped) maple. H. 30, W. 39, D. 21 in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

Born in Chino, California, to Lebanese immigrants, Sam Maloof left a promising career as a graphic designer and trained himself in woodworking. He became one of the most renowned furniture designers and makers in America and a leader of the Los Angeles–area modern design movement. Between 1988 and 2005, the Lynches commissioned twenty-five pieces from him, including this settee and the large dining table (below) and chairs. Influenced by modern Scandinavian furniture made in the 1950s, Maloof developed his own fluid sculptural style using an evolutionary approach to design in which he continually refined the craftsmanship. He focused on seating furniture, and his chairs are as comfortable to sit in as they are beautiful to look at. He emphasized the natural warmth of wood, simplicity of form, and handcrafted details. His signature is the use of contrasting dark wood to mark points of joinery.

|

|

Attributed to Major John Dunlap (1746–1792), Chest-on-chest-on-frame, 1775–1790, probably New Bedford, N.H., ca. 1820. Maple, painted. H. 77, W. 36½, D. 19¾ in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. “Whale tail” carvings on the cornice, a moustache-like motif at the skirt, and the condensed cabriole legs of this chest are hallmarks of furniture made by the Dunlap family of cabinetmakers for their rural New Hampshire clients. In the early nineteenth century the chest was updated with a grained surface to keep up with the trend for “fancy painting.” The case is made from maple, but has been painted to suggest a lively crotched veneer. The Lynches acquired the chest from the estate of well-known folk art collectors and scholars Bert and Nina Fletcher Little. |  |

|

| Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), Cedar and Red Maple, Lake George, 1921. Oil on canvas, 18½ x 15 inches. Peabody Essex Museum; Gift of Peter S. Lynch in memory of Carolyn Lynch (2018.72.3). © 2019 Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. O’Keeffe regularly spent summers in Lake George, New York, at the family home of her husband and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz. She loved to depict the lake in the fall, reveling in the seasonal color shifts and quiet after the summer tourists had left. O’Keeffe’s treatment of natural forms and unconventional contours in this painting demonstrate how she abstracted, combined, and layered the landscape in ways that were unprecedented in American art at that time. |

|

|

Lonnie Vigil (b. 1949), Nanbé Owingeh (Nambé O-ween-gé or Nambé Pueblo), Storage jar, 2002. Micaceous ceramic. H. 18, Diam. 21 in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

In the 1980s and 1990s, Lonnie Vigil helped revive the traditions of pottery making among the northern New Mexico pueblos. His hand-coiled jars and bowls are notable for their precise, even walls and luminous bodies. Led by the material’s elasticity and tactility, he has said: “I work for the simplest of forms. I allow the clay to do what it wants. The clay speaks.”

|

|

Gertrud Amon Natzler (1908–1971) and Otto Natzler (1908–2007). Glazed earthenware (left to right): Compressed bowl (ca. 1968). H. 7½, D. 11½ in. Footed vase (1972). H. 8½, D. 7½ in. Footed bowl (1965). H. 5, D. 6 in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

After fleeing their native Vienna in 1938 to escape the Nazi invasion, Gertrud Amon Natzler and Otto Natzler set up a studio in Los Angeles where they became central figures in the California design movement. They collaborated until Gertrud’s death and thereafter, Otto continued to work in new directions by hand-building more sculptural works. Their ceramics became a special collecting focus of the Lynches after they met Otto in the mid-1980s. Together, the Natzlers created works of unified form and surface color. Gertrud was responsible for throwing the earthenware pots on a traditional pottery wheel, using her hands to create thin-walled vessels, plates, and bowls of impeccable symmetry. She turned each finished form over to Otto for glazing. He mastered the unpredictable properties of the kiln and experimented with more than two thousand glaze recipes, ranging from brightly colored glass-like finishes to highly textured “lava” and “crater” glazes.

|

|

Marblehead Pottery, active 1904–1936, Marblehead, Massachusetts. Glazed earthenware. (front row) Ink Stand, 3½ x diam. 5½ in.; Vase, 4¾ x Diam. 4 in.; Vase, 3½ x Diam. 3 in.; Vase, 4 x Diam. ½ in. (back row left to right) Vase with leaf decoration, about 1910, design by Arthur Irwin Hennessey (1882–1923), decoration by Sarah Tutt (1859–1947) 8½ x 4 in. ; Vase with pinecone decoration, about 1910, design and decoration by Arthur E. Baggs (1886–1947) 12 ½ x Diam. 3½ in. ; Vase with leaf and berry decoration, about 1910, design by Arthur Irwin Hennessey (1882–1923) , decoration by Sarah Tutt (1859–1947) 11½ x 4¼ in.Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

The Marblehead Pottery firm produced a line of utilitarian wares following the principles of the Arts and Crafts Movement: dignity, simplicity and harmonious color. Most of the pieces were produced in a solid matte color. More expensive decorated wares, have repetitive patterns based on nature. Using three or four colors, sometimes with an incised outline, these schemes were integral to the overall simplicity of the form. These examples are part of large collection of the pottery assembled by the Lynches.

|

| Winslow Homer (1836–1910), Grace Hoops, 1872. Oil on canvas, 22 x 15 in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. In the decades following the Civil War, Homer’s vivid subjects and compositions resonated with national concerns. His many scenes of innocent children and adolescents in the countryside expressed hope for the future. Here, the girls play with a hovering hoop, which symbolizes the fleeting moment in time between their lives as children and their presumed future as mothers. |

|

|

| Frederick Carl Frieseke (1874–1939), On the River, 1908. Oil on canvas, 26 x 32 in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

Leading American impressionist Frieseke embraced the outdoors, saying, “it is sunshine, flowers in sunshine; girls in sunshine; the nude in sunshine, which I have been principally interested in for eight years, and if I could only reproduce it exactly as I see it I would be satisfied.” Frieseke began summering in the village of Giverny, France, a few years before he painted this work featuring his wife, Sadie. The village had become a thriving international artist colony after French impressionist Claude Monet settled there 20 years earlier.

|

|

William Bradford (1823–1892), Among the Ice Floes, 1878. Oil on canvas, 32 x 52 in. Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection. |

Inspired by a voyage to Melville Bay, Greenland, Bradford captured this disquieting scene of two sailors facing entrapment in the sea ice while securing their gear. By embracing the near monochromatic effects of the High Arctic twilight, the painter enhances the emotional impact of the moment. The sun filters at an acute angle, emphasizing the vast uniformity of the landscape.

Dean Lahikainen is the Carolyn and Peter Lynch Curator of American Decorative Art at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass. A Passion for American Art Selections from the Carolyn and Peter Lynch Collection is on view through December 1, 2019, at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass. PEM is the only venue for the show. For more information, visit www.pem.org.

A fully illustrated catalogue is available published by the Peabody Essex Museum and distributed by the University of Massachusetts Press (2019).

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2019 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.