A Tale Of Two Cities on Philadelphia’s Main Line

- At 86-1/2 inches tall, this slightly larger than life figure of Jack Tar is attributed to Jeremiah Dodge (ca. 1780–1860), a New York City carver of ship’s figureheads. The circa-1845 carved wood sculpture is the emblem of the couple’s marine collection and greets guests at the entrance to their home.

Ours was a typical Cambridge romance,” recalls the Radcliffe-educated wife, married to a Harvard-trained lawyer for the past fifty-six years. Their gracious home on Philadelphia’s Main Line reflects a tale of two cities—the colonial capitals of Boston and Philadelphia, their hometowns—as well as a tribute to the couple’s individual but intertwined interests

in American and Asian art.

As newlyweds, the husband and wife lived in Ardmore, Pennsylvania. They reared their children in nearby Gladwyne. After moving downtown to an I.M. Pei-designed townhouse in quaint Society Hill, they for a time displayed modernist sculpture by David Smith (1906–1965) and New York Color Field painting of the 1960s. To fill their next residence, this one overlooking Rittenhouse Square, they collected traditional American art of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

When the couple moved eleven years ago to a suburban aerie with a tree-lined vista of a historic tennis and racquet club, they oversaw extensive design changes to the spacious, single-floor residence, apportioning it into a welcoming foyer, expansive living room, formal dining room, cozy sitting room, kitchen, bedrooms, and offices. The wife’s fondness for color is expressed in a soft palette of pale lemon, ivory, salmon, and mint.

The couple’s sale several years ago of a Winslow Homer watercolor purchased from Childs Gallery in Boston in the 1950s financed their addition of a glass-enclosed, roof-top loggia. With views toward the city, the spring-green and raspberry colored sunroom houses the couple’s collection of sailors’ valentines and some of their Asian collections. “I like contrast,” says the wife. “My favorite uncle was in the U.S. Foreign Service. His wife was a genius at mixing decorative arts. She helped open my eyes to all cultures and their artistic endeavors.” The couple’s only flirtation with “period room” style is the dining room, which is an ode to Federal New England.

Boston-bred, the wife is a descendant of prominent Massachusetts merchants. Born in Philadelphia, the husband, like his father before him, became an expert in maritime law. Both husband and wife have long been active in philanthropic circles. He founded the Philadelphia Maritime Museum, now the Independence Seaport Museum, in 1960. Both serve on the board of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; she as an active trustee, he in an emeritus role.

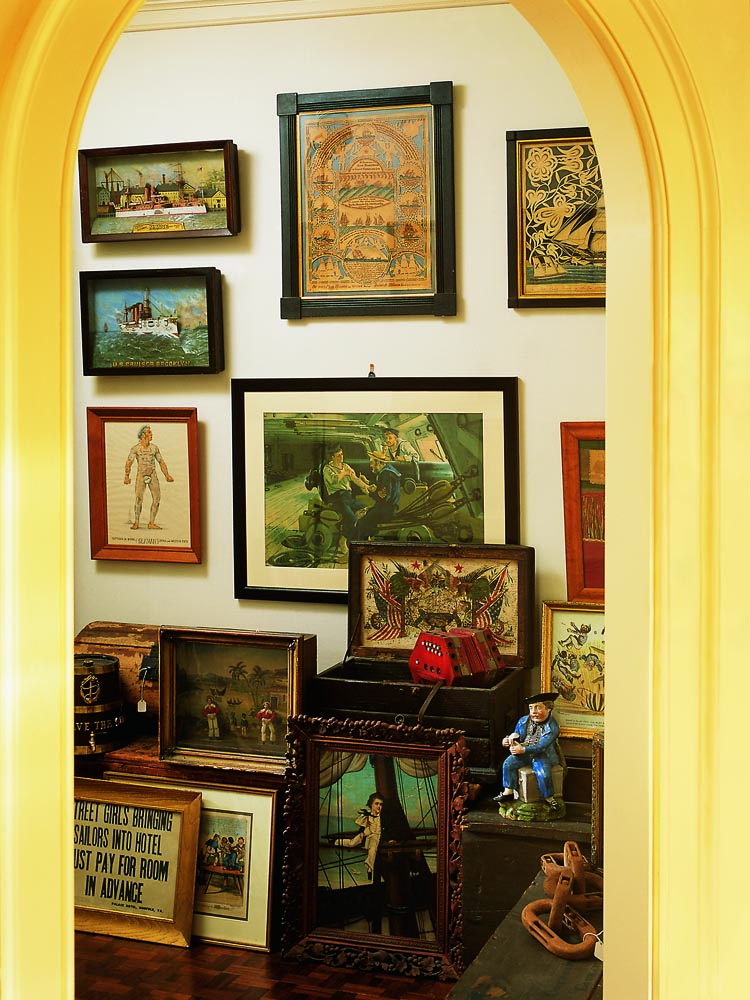

Recalling how and when he became a collector of marine antiques, the husband recounts, “As a seven year old in 1927, I gave fifty cents to save America’s most historic ship, the USS Constitution, ‘Old Ironsides.’ For that donation, I received a small anchor made of metal and wood salvaged from the ship.” He still owns the anchor. By the early 1950s, the husband had narrowed his pursuit to objects related to the port of Philadelphia and the Delaware River, along with antique American and English paintings, sculpture, prints, manuscripts, and other artifacts depicting the daily life of sailors. His fascination with the latter culminated in Marine Art & Antiques: Jack Tar, A Sailor’s Life, 1750–1910 (1999), written with Rodney P. Carlisle. A companion exhibition, Life of a Sailor: A Collector’s Vision, opened at the Independence Seaport Museum in September, 1999.

Greeting visitors in the entranceway is the jaunty, slightly larger than life figure of “Jack Tar,” the prototypical sailor and mascot of the couple’s marine collection. Attributed to Jeremiah Dodge (ca. 1780–1860), a New York City carver of ship’s figureheads, the painted wood sculpture of circa 1845 is one of the husband’s most prized possessions. Having first admired it in a Manhattan gallery, he later purchased the folk-art icon from Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, dealer Alan Granby.

In his book, the husband describes the formation of his collection over time: “From top dealers and great auction houses to house sales and flea markets—anywhere with a glimmer of a chance of yielding something interesting was fair game.” He credits, among others, dealers Charles Childs, Harry Shaw Newman, Ron Bourgeault, Alan Granby and Janice Hyland, John Rinaldi, Carl Crossman, Diana Bittel, Norm Flayderman, Elinor Gordon, and Martyn Gregory with assisting his search.

An interest in flagged American ships led the husband to the work of Thomas Birch (1779–1851). Over a mahogany and bird’s-eye maple Federal sideboard in the dining room hang three oil on canvas paintings by the English-born Philadelphia marine artist. The collectors loaned Birch’s War of 1812 battle scene, US Frigate United States defeating HMS Macedonian on 25 October 1812 (1813), to President John F. Kennedy, who displayed it in the Oval Office. “We had a family game of finding my painting in the many published photos of Kennedy and his advisors at the time,” says the husband.

“While he was going gung-ho with maritime antiques, I got interested in American furniture,” says the wife, who favors coastal Massachusetts and New Hampshire pieces made between 1750 and 1820. The couple primarily bought from Israel Sack, Inc., in New York, whose exacting taste for fine proportion and restrained ornamentation they shared. Their first important furniture purchase, in 1957, was a Boston Chippendale serpentine-front chest of drawers with a molded top and ball-and-claw feet. Along with a Salem, Massachusetts, Chippendale bonnet-top high chest of drawers and a Federal inlaid mahogany breakfront bookcase, probably from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, it is a highlight of the collection.

Over time the couple acquired their representative array of American paintings on canvas and paper: portraits by Philadelphia masters Rembrandt Peale and Thomas Eakins; landscapes by Thomas Doughty and William Trost Richards; still lifes by William Merritt Chase, Severin Roesen and Levi Wells Prentice; and early modernist works by John Marin, Charles Burchfield, and Joseph Stella.

“A big lady in black bombazine—absolutely terrifying,” says the wife, recalling from early childhood an elderly relative, American impressionist artist Lilla Cabot Perry (1848–1933). The couple own several Perry paintings and drawings, including The Pink Rose of 1910, a large, luscious three-quarter length oil on canvas portrait of the artist’s daughter. In the wife’s room, a Perry pastel of Giverny—where the artist, a friend of Monet, summered for nine years—joins Childe Hassam’s (1859–1935) Moonrise at Sunset, Cos Cob of 1902. Two John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) charcoal on paper portraits of the wife’s parents date from 1922 and 1923. “My paternal grandmother knew him quite well,” says the wife.

In the living room on opposite walls are Morning Glory Pool by John Henry Twachtman (1853–1902), and The Bathers, an oblique nod to Matisse by David Park (1911–1960), a Boston-born artist who was a leader of the Bay Area figurative movement. Park, the couple later learned, was also the son of the Unitarian minister who married them.

“It’s a toss up as to which painting is our favorite. The Twachtman is finesse but the Park is umph,” says the wife. Flanking the Park are views of Gloucester, Massachusetts, by Maurice Prendergast (1858–1924) and Stuart Davis (1894–1964). Though painted only a decade apart, in 1906 and 1916, respectively. they illustrate the abrupt transition from realism to abstraction that took place in the early twentieth century.

Both Philadelphia and Boston were major ports in America’s late eighteenth and early nineteenth century trade with China. Suitably, two circa 1835 oil on canvas Canton scenes by Lam Qua (1801–1860) hang in the couple’s dining room. From understated Japanese Arita porcelain to voluptuous Indian statuary, the couple’s collection of Asian art is extensive. A gilded and painted Kano school Japanese screen, which occupies a place of honor in the couple’s foyer, is an inherited piece from the wife’s family, who had long cultural and commercial ties to the Far East. It wasn’t until the husband served as U.S. Commissioner General for the 1974 Expo in Spokane, Washington, and the Consul General for Japan in Philadelphia between 1978 and 1990 that the couple became seriously interested in Asian art, acquiring Japanese prints, porcelain and lacquer; Chinese Ming furniture; and Indonesian trade goods, among other artifacts. The wife even returned to school to study Southeast Asian sculpture, her greatest love.

On a buying trip to London on behalf of Philadelphia’s Fairmont Park Art Association, the couple made their first visit to Spink. They subsequently purchased many Southeast Asian sculptures for their own collection from the prominent dealers.

“It took my breath away,” the wife recalls of the eleventh-century Khmer Baphuon period stone torso that was their first major acquisition. Another favorite piece is a late-third- or early-fourth-century A.D. Gandaharan gray-schist carving of a Bodhisattva, now housed in a niche constructed especially for its display.

“Connections make history much more interesting and meaningful”, the husband believes. From a little boy’s souvenir anchor to masterworks of American painting and serene relics of ancient Asia, this well-edited collection is an unusually personal evocation of two lives, well lived, together.