A World of Connections at the Peabody Essex Museum

Winter Antiques Show Loan Exhibition

As the featured museum at the 2014 Winter Antiques Show, the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) is presenting Fresh Take in the spirit of a contemporary cabinet of curiosity. Approximately fifty of our most important works represent the depth and breadth of our 1.8 million objects, twenty-four historic properties, and Phillips Library. Cumulatively, the works suggest a dialogue between the past and the present and propose global connections among multifaceted expressions of creativity and humanity.

PEM’s American art holdings have historically emphasized New England’s early portraiture and decorative arts, especially furniture, silver, glass, ceramics, and textiles. The collection’s nucleus is furniture created in Salem’s heyday as a major production center. Today, our purview embraces American painting, Native American art, and contemporary studio craft and design. The Native American collection represents 10,000 years of indigenous visual expression from North, Central, and South America. Its range of media and object types—textiles, ceramics, sculpture, functional and ceremonial art objects, paintings, and works on paper—complements its pioneering focus on contemporary expressions since the 1990s.

Continued at the bottom of the page....

This card table was one of the original furnishings made for Cleopatra’s Barge, America’s first private luxury yacht, built in Salem in 1816 for George Crowninshield. The boat created a sensation in 1817 on its maiden voyage to Europe, where thousands of visitors at Mediterranean ports marveled at the opulent interior decoration and furniture. The table and its mate, made to match a pair of painted settees, reflect the British Regency style with classically inspired accents, including gilt mounts on the base, pierced brass fretwork in a Greek key pattern on the top surface, and carved acanthus leaves on the harp or lyre support.

—Dean Lahikainen, Carolyn and Peter Lynch Curator of American Decorative Arts

The initials and date carved on the central octagon stand for Joseph and Bathsheba Pope and the year of their marriage. The Popes, who were Quakers, lived in Salem Village (today Danvers, Massachusetts) and were principal accusers during Salem’s witch trials in 1692. One of four known examples of this form, the cabinet is among the few pieces of seventeenth-century American furniture to retain its original finish, now darkened with age. The façade is a hinged door with a lock that protects ten small drawers to store precious items. Red paint on selected moldings and black paint on the spindles, feet, and smaller elements created dynamic contrast to the cabinet’s once bright yellow oak.

—Dean Lahikainen, Carolyn and Peter Lynch Curator of American Decorative Arts

“Mr. George Ropes’ dumb boy is very successful at painting,” wrote William Bentley, Salem’s great diarist. Born deaf, Ropes Jr. also painted signs and carriages. This painting successfully advertises Salem while celebrating civic life in the United States. Ropes Jr. accentuates Salem Common’s then famous Lombardy poplars to express the order, pomp, and circumstance of the military maneuvers being practiced. But the artist also uses this swelling line of trees as an innovative way to focus attention on the spectacle of training days for soldiers and civilians. The poplars create a verdant proscenium for the foreground’s promenading families, white and African American.

—Austen Barron Bailly, George Putnam Curator of American Art

A young sailor created this object for his ship’s master as a token of respect and friendship. It is a tour-de-force scrimshaw—the art of engraving on whale teeth, bones, and baleen—in part because the artist also inscribed a sixteen-stanza poem entitled To a Whale’s Tooth that opens: “If you could Speak, what tales you’ld tell/Thou tooth, from the jaws of a sperm whale:/You’ld tell the secrets of the mighty deep/Of riches lost, whitch [sic] Mermaids keep.”

— Daniel Finamore, Russell W. Knight Curator of Maritime Art and History

A serious amateur photographer, Sarah Lawrence Brooks was better known for being born into the founding family of Lawrence, Massachusetts, and marrying into an equally prominent one. She poses before a marble-top table embellished with mythological figures and gracefully touches a small bronze statue of a Greek deity from her collection. The glowing sunset and colonnade signal Sargent’s embrace of classical traditions that this sitter, her tastes, and his portraiture represent. Mrs. Brooks epitomizes the pedigree of Sargent’s sitters in 1890. That year the artist returned from Europe to Boston to satiate demand for his portraits and to receive his commission to execute murals for the Boston Public Library.

— Austen Barron Bailly, George Putnam

Curator of American Art

The 1821 guide to the East India Marine Society’s collection identifies this as “a portrait of Eshing, a Silk Merchant in Canton, by a Native artist.” Spoilum was one of the first Chinese artists to work in a Western style and adeptly captured his sitters’ likenesses and personalities. Best known for painting English and American merchants, the artist also produced portraits of their Chinese counterparts. This flat, linear portrait remains in its original Western-style, gilded-wood frame, made in Guangzhou by Chinese carpenters. Samples of the silk Eshing sold survive in Benjamin Shreve’s papers, now in PEM’s Phillips Library.

— Karina Corrigan, H. A. Crosby Forbes

Curator of Asian Export Art

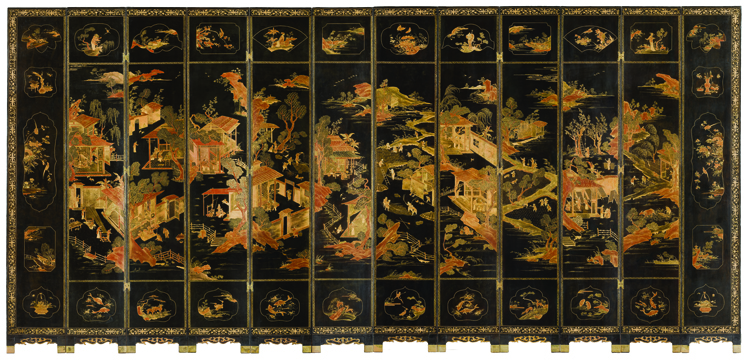

Cantonese lacquer artists created this lavishly decorated twelve-panel screen for Sir John Eccleston, a London silk merchant and director of the East India Company. The front panels show Eccleston’s coat of arms and a Chinese court scene. Unusually, the back illustrates the cultivation of rice and the production of silk, images taken from a 1696 book of woodblock prints commissioned by the Emperor Kangxi. These scenes of silk production, which were widely adapted by Chinese artists in different media, may have had special meaning for Eccleston. As a successful silk merchant, he could afford such works of art, precisely because he traded in silk.

— Karina Corrigan, H. A. Crosby Forbes Curator of Asian Export Art

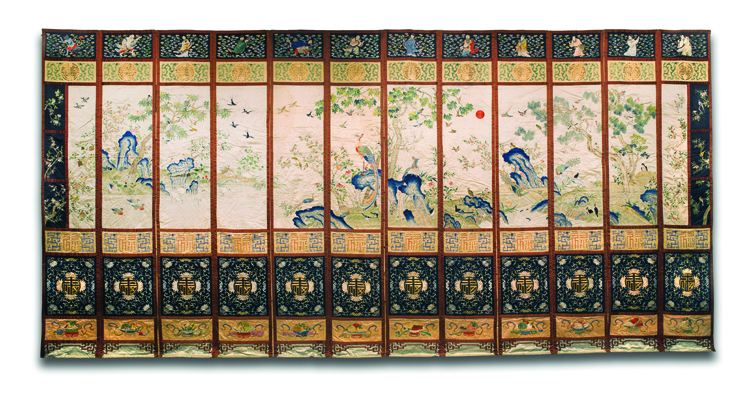

This rare set of silk panels creates a splendid illusion of a carved and painted wood screen. Elaborate embroidery and applied characters, deities, fruit, and vegetables convey wishes for health, wealth, and prosperity. The central scene with two phoenixes represents peace and celebration. Salem resident William Franklin Spinney, a senior maritime customs official in China for more than thirty years, owned these panels, perhaps to evoke fond memories of Wuhu, the city he described as “the best shooting district of China,” where “pheasants, wild fowls & snipe abound.”

— Daisy Yiyou Wang

Curator of Chinese and East Asian Art

Buddha relics—the remains of holy persons or other precious substances—are considered material and spiritual treasures in Japan. The portable reliquary with its relic-holding sphere, known as a wish-granting jewel, was the focal point in Buddhist rituals to bring miraculous power and blessings to worshipers. The tiered pedestal, which symbolizes the center of the universe, Mount Meru, bears an inscription that identifies the Kōki-ji temple in Osaka as its place of origin, and also states its maker and date of consecration. The reliquary’s donor, Charles Goddard Weld, was a seminal patron and collector of Japanese art and culture in the early twentieth century.

— Daisy Yiyou Wang

Curator of Chinese and East Asian Art

A Native Hawaiian master carver created this spectacular temple image of Kūkà’ilimoku, or Kū, for Kamehameha I, the formidable Hawaiian chief and warrior. One of three monumental surviving representations in the world, Kū is the most powerful among four Native Hawaiian deities. His power manifests in many forms: as god of the sea, agriculture, fertility, healing, and war. Kū’s dynamic and protective energy is palpable, from his menacing open mouth, to the surface treatments emphasizing his feather headdress and sculpted muscles.

— Karen Kramer

Curator of Native American Art and Culture

This mask represents a Haida noblewoman, distinguished by her prominent lower-lip ornament (labret), which indicates beauty, high rank, and individual, family, and cultural identity. Never intended for ceremonial use, this mask is one of the earliest, finest examples of Northwest Coast souvenir art, made during the height of the Pacific fur trade in sea otters. About fifteen known masks and figurines exist in the world, all created between 1820 and 1840 by the same master carver. Haida women relinquished the practice of wearing labrets due to pressure from nineteenth-century missionaries, but their depiction in art continues today.

— Karen Kramer

Curator of Native American Art and Culture

America’s great marine painter Fitz Henry (Hugh) Lane was at an artistic turning point when he created this scene. His depiction of the Southern Cross is in the grand tradition of ship portraits, yet his equal attention to the luminous effects of light and water hints at his increasing interest in painting seascapes that emphasize nature’s power and beauty.

— Daniel Finamore, Russell W. Knight Curator of Maritime Art and History

With its striking mirror reflection and evocative atmosphere, this photograph ranks among Thomson’s most romantic works.

It was not made as a fine art photograph, but rather for a topographic survey documenting key sites on the Min River between the port city of Fuzhou and the inland city of Nanping. Thomson photographed the landscape, everyday life, and cities and villages along the river. Commercially, the venture was a failure. Of the forty-five sets supposedly made, only six are known to survive, two of which the museum owns.

— Phillip Prodger

Curator of Photography

In a tradition dating back some 1600 years, each Japanese emperor is entombed in a burial mound. The tomb depicted here is that of the first emperor, Jimmu. Applying a quintessentially Western approach to this most Japanese of subjects, Ina adopted the formula of legendary German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, photographing from a slight elevation against a neutral gray sky, with the subject sharp and perfectly centered. The result is a unique hybrid of Japanese and Western aesthetics.

— Phillip Prodger

Curator of Photography

...Continued from above.

Our Chinese holdings excel in textiles, religious, decorative, and celebratory objects, and imperial portraits, porcelain, and sculpture, and also features the only complete historic Chinese house relocated to the United States. Predating Commodore Matthew Perry’s arrival in Japan in 1854, the Japanese collection includes ceramics, lacquer ware, textiles, paintings, religious objects, and furnishings. PEM’s Korean holdings focus on the Choson dynasty (1392–1910), especially during the late nineteenth century, when the museum played a major role in establishing diplomatic relations between Korea and the United States. The Indian collection emphasizes modern and contemporary painting created after the country’s independence in 1947. Our Asian export collection encompasses works in all media made by artists in China, Japan, India, and Indonesia.

The maritime collection includes international examples of personal and collective experiences of the sea from ancient to contemporary times. American and European paintings and works as diverse as scrimshaw, navigational instruments, ship models, and charts represent key strengths.

The Oceanic collection encompasses art and cultural objects made by more than thirty-six island groups in Hawai’i, the Marquesas, New Zealand, Fiji, the Austral and Cook Islands, Easter Island, Tonga, and Samoa. The African collection features religious and secular works from Ethiopia, Northern Africa, the Sub Saharan, and the Congo.

PEM’s photography collection numbers approximately 800,000 images and represents hundreds of techniques, from paper negatives to digital media. Its nineteenth-century photographs of Asia, Native America, New England, Oceania, and maritime environments are unrivaled. Acquiring modern and contemporary photographs and films is a current priority.

With the promised gift of Iris Apfel’s “Rare Bird of Fashion” collection in 2011, the museum launched international modern and contemporary fashion as its most recent collecting initiative. Our holdings in international historic costumes and textiles already included a world-class concentration in shoes and American women’s fashion and accessories from 1820 to 1930.

Complementing these global holdings are the archives of the museum’s Phillips Library, one of the largest libraries associated with an American art museum and one of New England’s major research libraries. Ships’ logs, first-hand accounts, commercial papers, and rare books and maps contextualize regional, national, and international networks of art, society, and culture.

— Lynda Roscoe Hartigan, James B. and Mary Lou Hawkes Chief Curator