Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture

|

Alexander Humboldt (1769–1859) was arguably the most important naturalist of the nineteenth century. Born in Prussia, what is now Germany, he lived to his ninetieth year, published more than thirty-six books, traveled across four continents, and wrote well over 25,000 letters to an international network of colleagues and admirers. He was a pioneer in finding the connections among aspects of the physical world and seeing in the entire planet a “unity of nature.”

In 1804, after traveling five years in South America and Mexico, Humboldt spent six weeks in the United States. In these six weeks, Humboldt—through a series of lively exchanges of ideas about the arts, science, politics and exploration with influential figures such as President Thomas Jefferson and artist Charles Willson Peale—shaped American perceptions of nature and the way American cultural identity became grounded in the natural world.

Humboldt was inspired by American democracy, excited for American expansion, and concerned for all races living within its borders. He came to consider himself “half an American,” believing that this country’s future would be measured by contributions to science and exploration, by the abolition of slavery, and by establishing policies to achieve peaceful co-existence with Native Americans. Humboldt associated nature with an inherent right to individual freedom for all humankind. He described the unique features of the American landscape as monuments equal to the architectural wonders of the ancient world.

Over the next half-century, Humboldt became a voice of authority as a scientist and explorer, encouraging America to implement its founding ideals as the country took its place on the world stage. An exhibition Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, centers on the fine arts as a lens through which to understand how deeply intertwined Humboldt’s ideas were with America’s emerging identity, grounded in an appreciation of nature. He believed that the arts were as important as the sciences for conveying the resultant sense of wonder in the interlocking aspects of our planet. His lasting influence through art reveal how the American wilderness became emblematic of the country’s distinctive character.

Humboldt helped to shape the careers and artworks made by some of the most significant American artists working during his lifetime. These artists advocated for the power of the fine arts to create a nature-based aesthetic associated with the Hudson River school and the development of the national parks. More than 100 paintings, sculpture, maps, and artifacts are included, with artworks by Albert Bierstadt, Karl Bodmer, George Catlin, Frederic Church, Eastman Johnson, Samuel F.B. Morse, Charles Willson Peale, John Rogers, William James Stillman and John Quincy Adams Ward, among others. Church, an esteemed painter of the Hudson River school, features prominently in the exhibition. He idolized Humboldt, going as far as trekking in the naturalist’s footsteps in South America.

|

|

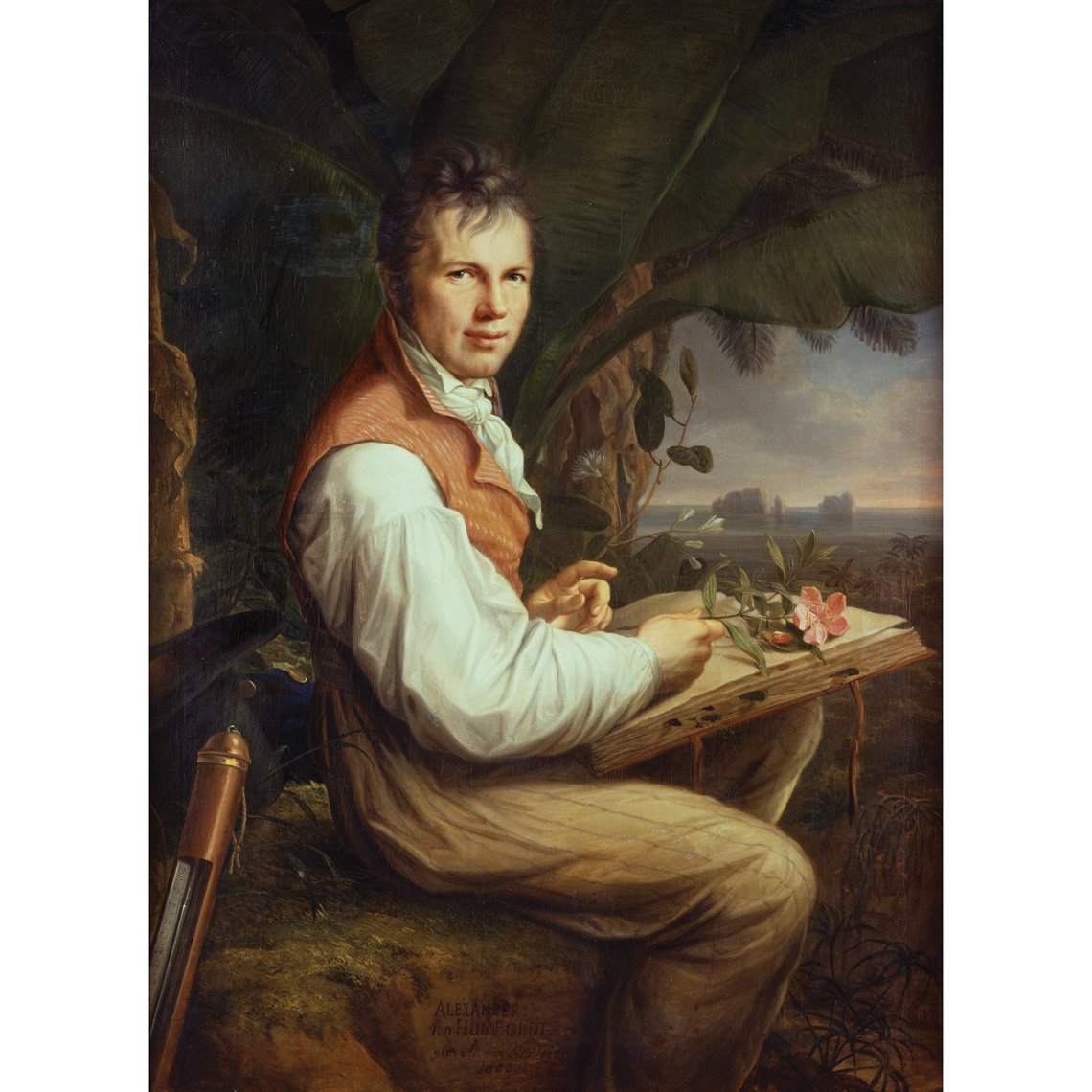

Friedrich Georg Weitsch (1758–1828), Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), 1806. Oil on canvas, 49⅝ x 36⅜ in. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. Photo: bpk Bildagentur / Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Germany / Klaus Goeken / Art Resource, NY. |

Weitsch painted Humboldt’s portrait shortly after his return to Europe from the United States. He captures the Prussian naturalist’s ease in familiar surroundings, seated outdoors with his plant specimens, travel journals, and his favorite barometer. During a five-year trip across South America and Mexico, Humboldt began gathering the data and specimens that fueled his writing. He brought together his ideas in a multi-volume book he titled Kosmos (in English, Cosmos), which became an international best-seller and made Humboldt one of the best known and widely admired public figures in the world.

|

|

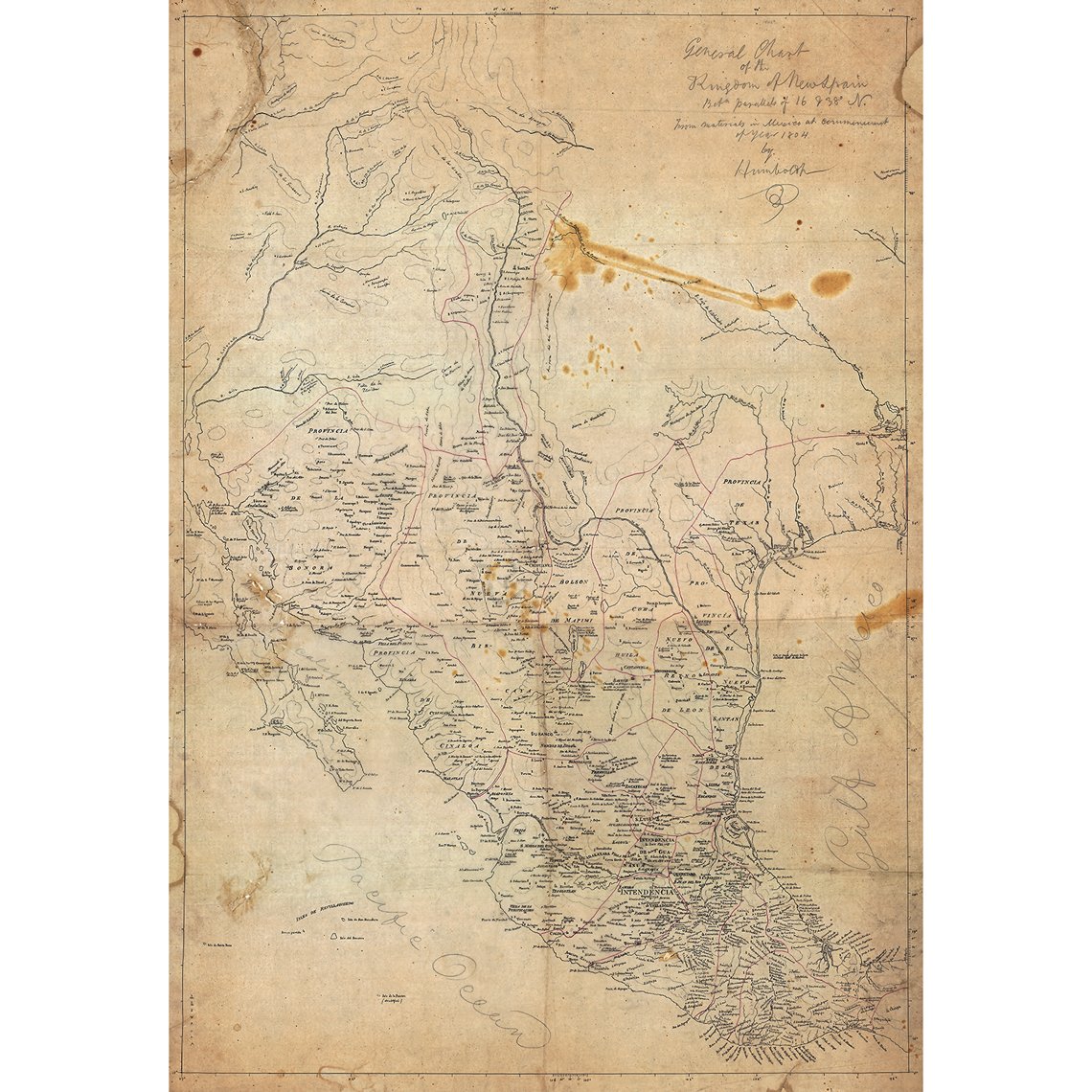

Copy after Alexander von Humboldt, General Chart of the Kingdom of New Spain between Parallels of 16 & 38° N., from Materials in Mexico at the Commencement of year of 1804, 1804. Pencil and ink on tracing paper, 37¾ x 26 inches. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. |

This is a copy of the map of North America Humboldt shared with Thomas Jefferson. Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin marveled that it contained more and better information than was available on any known map of the continent. In addition to mountains and rivers, Humboldt included territorial boundaries, major towns, churches, and silver mines. Jefferson queried Humboldt about the people and the industries populating the land newly acquired from France as part of the Louisiana Purchase. The Prussian traveler also provided Jefferson with the results of his research, including population statistics.

|

|

Skeleton of the Mastodon, excavated 1801–1802 by Charles Willson Peale. Bone, wood, and papier mâché, approx. 118 × 177 × 65 in. Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt, Germany. Photo: Wolfgang Fuhrmannek, © Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt. |

When this mastodon was excavated, some of the bones were missing or damaged. Moses Williams, a free man of color working for Peale’s Museum, carved the missing bones along with Peale’s son Rembrandt and Philadelphia sculptor William Rush. Mastodon tusks did not always survive excavation. Though Peale found a five-foot-long tusk, it broke into several pieces and was too fragile to be repaired for display. As a result, the tusks on Peale’s skeleton were made from papier mâché. There were theories about the orientation of the tusks, which were originally displayed facing downward, like a saber-tooth tiger. Comparison of multiple mastodon skeletons provided the evidence that determined the tusks faced up and forward, as you see them on this skeleton. By the time Charles Willson Peale painted The Artist in His Museum, the tusks on this skeleton were once again oriented correctly, facing up.

|

|

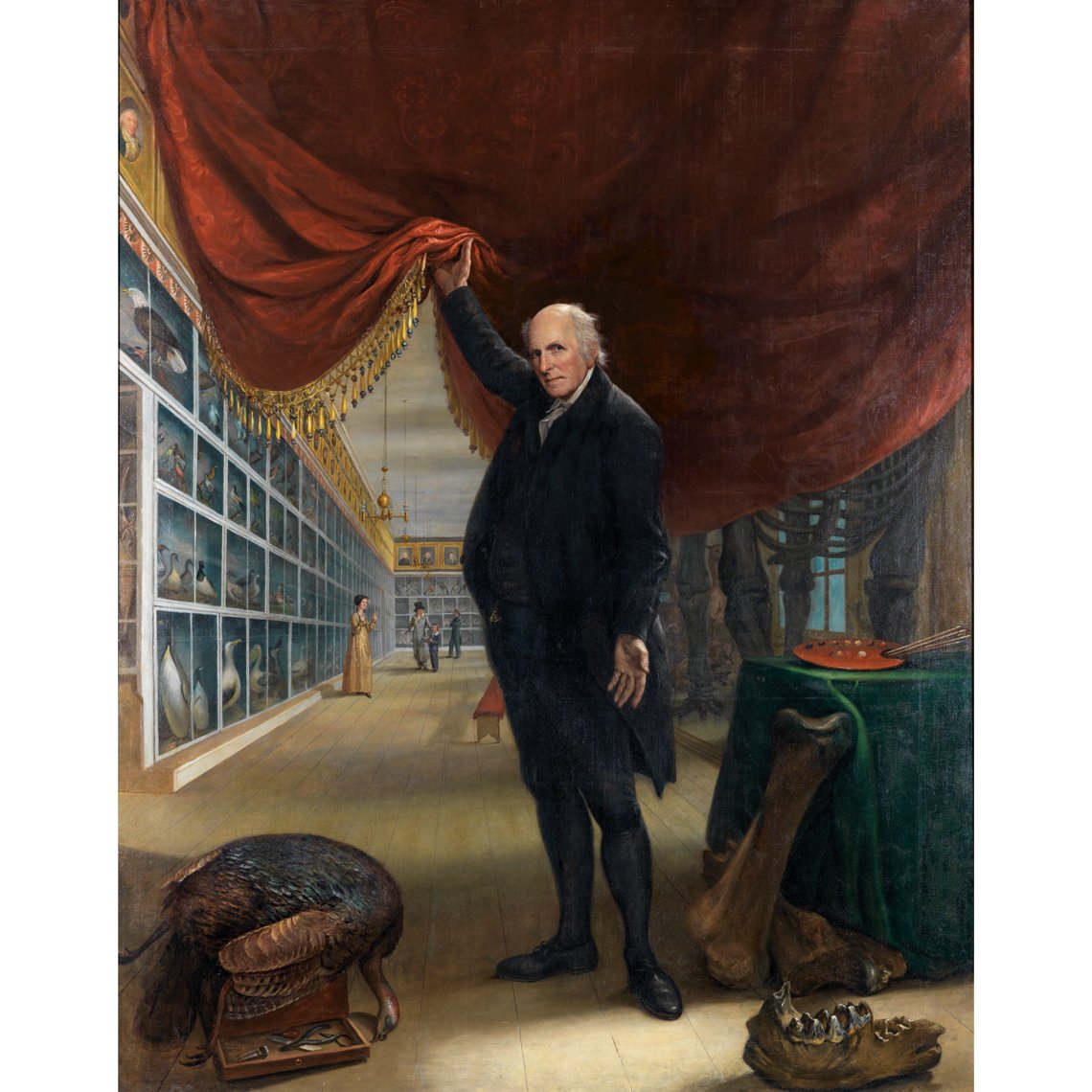

Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), The Artist in His Museum, 1822. Oil on canvas, 103¾ x 79⅞ inches. Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia; Gift of Mrs. Sarah Harrison (The Joseph Harrison Jr. Collection). |

Peale was an artist, naturalist, and patriot. In 1784 he founded a museum designed as “a world in miniature.” He intended its exhibits to teach Americans to see their cultural identity in the nation’s democratic ideals and its natural history. In this painting, he constructed a self-portrait that seamlessly merges his own identity with that of the museum. Peale’s taxidermy tools and his loaded palette and brushes imply an artist still ready and capable. Behind the curtain is the mastodon, the centerpiece of Peale’s Museum.

|

|

Frederic Edwin Church, Niagara, 1857. Oil on canvas, 40 x 90½ in. National Gallery of Art, Corcoran Collection (Museum Purchase, Gallery Fund). |

Church’s Niagara was considered the finest landscape painting of its day. Church experimented with the scale and proportions of his canvas and adjusted his focal point to absorb a wide range of terrestrial and atmospheric phenomena that would convey the range of his travels, observations, and insights. Humboldt saw the panorama format as ideal for “increase[ing] . . . the force of these impressions” from nature. What Humboldt accomplished in writing served as inspiration for what Church would create in paint. One critic termed Church’s Niagara the eighth Wonder of the World. Like the mastodon, Niagara Falls represented an impressive feature often interpreted as a national and cultural icon.

|

|

Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), Aurora Borealis, 1865. Oil on canvas, 56 x 83½ in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Eleanor Blodgett (1911.4.1). Photo by Gene Young. |

Frederic Church saw himself as an American Humboldt, steeped in science as well as art. He chose challenging subjects: falling water, erupting volcanoes, ancient icebergs, and the electromagnetic impulses of the aurora borealis. Church often infused his paintings with layers of metaphorical meaning. Here an explorer’s ship is trapped in the ice. The Canadian coast rises above the stranded ship; to the west lies Ireland, the terminus of the transatlantic cable. Overhead the auroras snake across the sky, their colorful arcs suggesting the snapped cables that plagued his friend and patron Cyrus Field for years as he strove to make trans-oceanic electronic communication a reality. Ships might be trapped in solid ice, but electricity promised the possibility of global communication if it could only be harnessed. The beauty of the auroras and Church’s appreciation of the science that explains them remind us of Humboldt’s declaration that “nature and art are clearly united in my work”—words that were equally true for Church. In the end, we understand that both are essential to our appreciation of the interconnectedness of all aspects of nature.

|

|

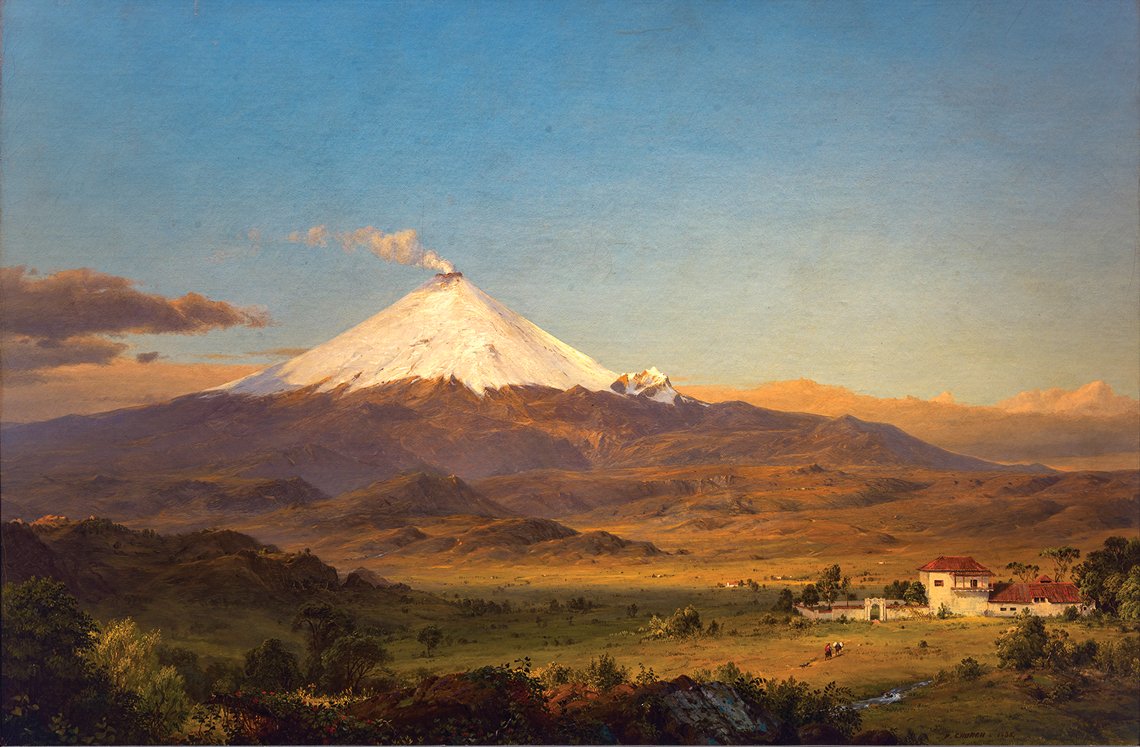

Frederic Edwin Church, Cotopaxi, 1855. Oil on canvas, 28 x 42 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Frank R. McCoy (1965.12). Photo by Gene Young. |

Church’s first trip outside the United States was an ambitious seven-month journey through South America with his friend and patron, Cyrus Field, in 1853. The two men used Humboldt’s book Views of the Cordilleras as a guidebook, following parts of the explorer’s itinerary and staying in some of the same places. Church painted this work for Field as a memento of their trip. He included a haçienda where Humboldt had stayed in 1802, and in which they had also stayed. Church used Humboldt’s engraving of Cotopaxi from the title page of Views of the Cordilleras to compose this painting. He also consulted Humboldt’s Picturesque Atlas, with its large-format color engravings from Humboldt’s travels through South America.

|

|

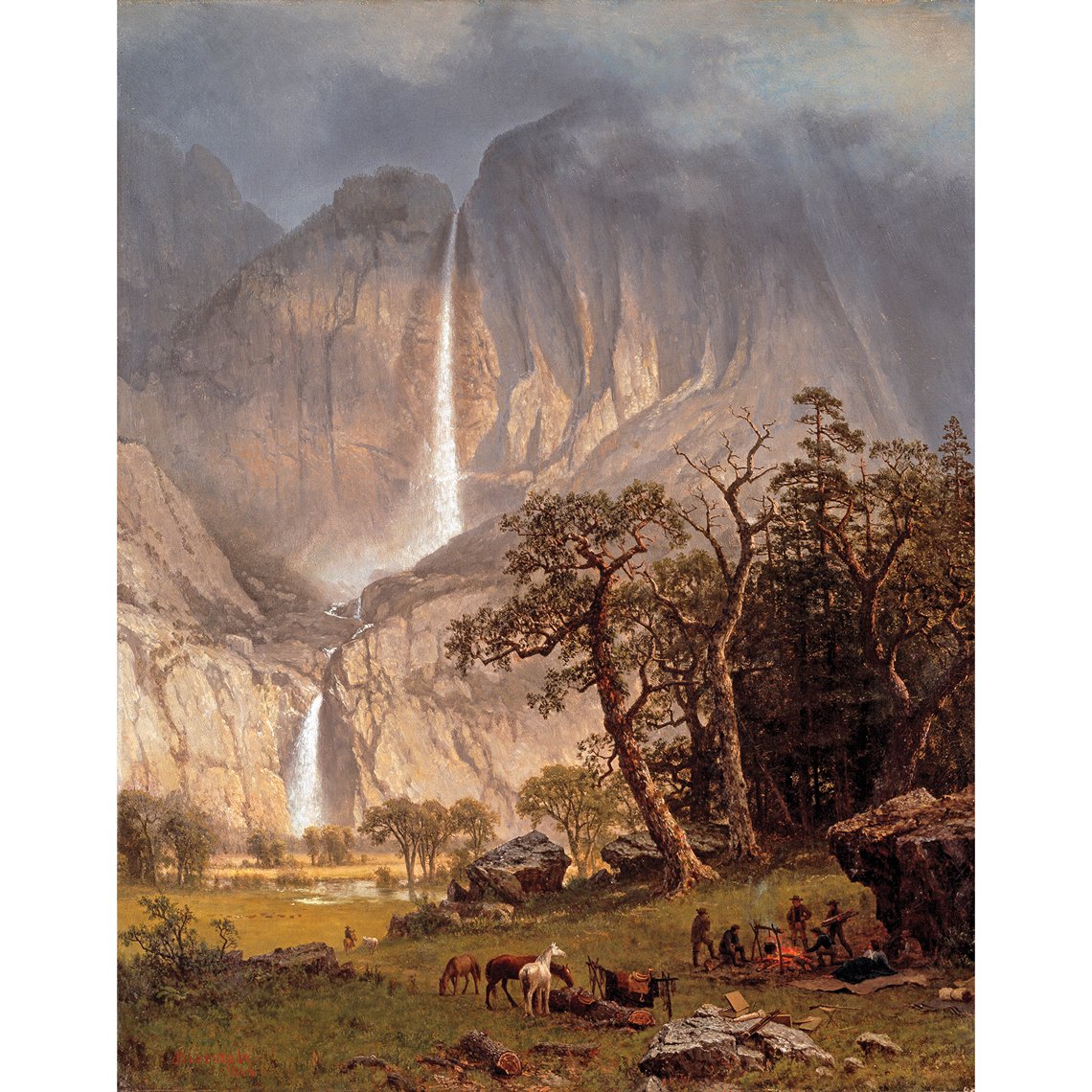

Albert Bierstadt, Cho-Looke, The Yosemite Fall, 1864. Oil on canvas, 34¼ in. x 27⅛ in. Timken Museum of Art, Putnam Foundation. |

Bierstadt was inspired to paint Yosemite after seeing Carleton Watkins’s photographs in a New York gallery in 1862. He based his composition on Watkins’s view of Yosemite Falls. Both artists captured the magnificent topography of Yosemite, which became associated with California’s entry into the Union as a free state in 1850. In 1864, the year Bierstadt painted this view, President Abraham Lincoln set aside Yosemite as a protected reserve, in recognition of the enduring power of American landscapes to serve as symbols of the nation’s cultural aspirations.

|

|

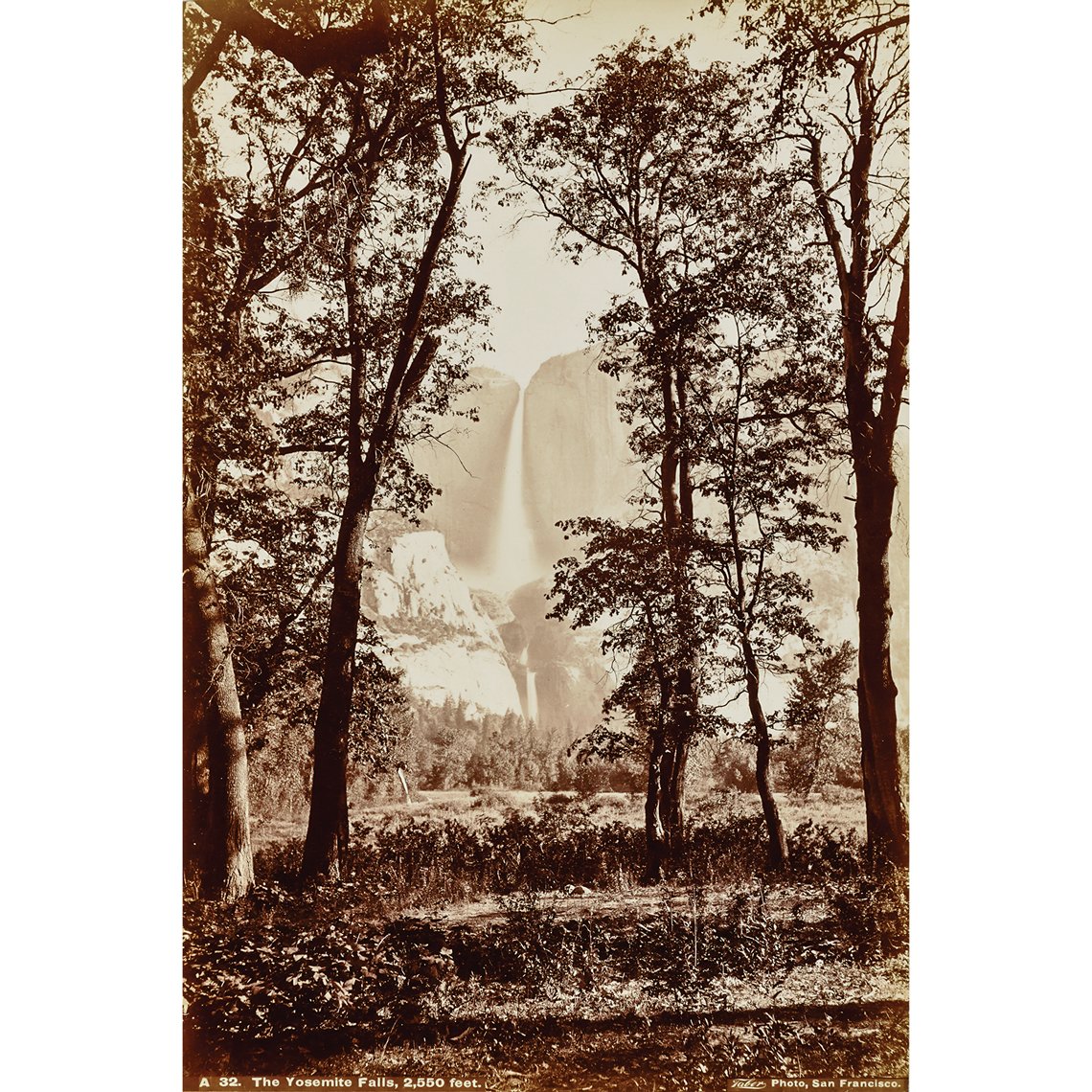

Carleton E. Watkins and Isaiah West Taber, Yosemite Falls, ca. 1865–66, printed after 1875. Albumen silver print, 12 x 8 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase from the Charles Isaacs Collection made possible in part by the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment (1994.91.282). |

Watkins established the canonical views of Yosemite, introducing this unique landscape to eastern audiences when his “mammoth-plate” photographs went on view in New York in 1862. John C. and Jessie Benton Frémont were major patrons of Watkins’s photographs, which they saw as symbolic of America’s commitment to freedom. Abraham Lincoln signed the legislation setting aside Yosemite as a federally protected landscape in March of 1864, in part in response to the power of these photographs. Watkins’s photographs were among the artworks that helped define this California landscape as a national icon associated with the cause of liberty during the American Civil War.

|

|

John Quincy Adams Ward, The Freedman, 1863. Bronze, 19½ x 1411⁄16 x 9⅝ in. Boston Athenæum; Gift of Elizabeth Frothingham (Mrs. William L.) Parker (1922). Photograph by Jerry L. Thompson for the Boston Athenæum. |

Alexander von Humboldt believed in the equality of all races and would advocate for the abolition of slavery throughout his life. Ward’s sculpture of an enslaved man about to rise up, his shackles broken, is the most powerful abolitionist sculpture made during the Civil War. For this cast, a fragment of one of the guns from Fort Wagner, South Carolina, where Robert Gould Shaw and the troops he led, the all-black Massachusetts 54th Regiment, were massacred. The fragment of the cannon served as an emblem of the regiment’s sacrifice as well as a sober reminder of the war’s toll on the country.

|

|

Eastman Johnson, The Old Mount Vernon, 1857. Oil on board framed: 23⅜ x 34½ in. Mount Vernon Ladies' Association; Purchased with funds courtesy of an anonymous donor and the Mount Vernon Licensing Fund (2009). Photo Courtesy of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. |

Humboldt visited Mount Vernon during his trip to Washington, D.C., in 1804. There he confronted the conundrum at the core of American democracy—the nation’s admiration for George Washington as a revolutionary war hero and first president, and its adherence to the perpetuation of slavery. Johnson’s painting, made in 1857, grapples with the same issues. Instead of presenting the portico of the mansion facing the Potomac River, the artist shows the slave quarters attached to the rear of the house. Humboldt never gave up hope that the United States would abolish slavery and make the benefits of American democracy available to all who lived there.

|

|

George Catlin (1796-1872), Máh-to-tóh-pa, Four Bears, Second Chief, in Full Dress, 1832. Oil on canvas, 29 x 24 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum; Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison Jr. (1985.66.128). Photo by Gene Young. |

Humboldt was horrified by President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830, which broke existing treaties and forced the relocation of entire communities to make way for white settlements. Two people who became close to Humboldt responded to concern for the survival of native communities along the Missouri River. One was self-taught artist and amateur ethnographer George Catlin. In 1832 Catlin made his first extended trip upriver from St. Louis to study native communities. As was the custom, Catlin arrived bearing gifts to exchange for the opportunity to meet the Mandan (Nųmą´ khų´ ·ki) chief Mató-Tópe, also called Four Bears, and to negotiate painting his portrait. Mató-Tópe chose how he intended to be portrayed, his stance and his regalia asserting his authority. He granted Catlin extensive access to the community and permitted the artist to witness their sacred O-Kee-Pa ceremony.

|

|

After Eduard Hildebrandt, Humboldt in His Library (1818-1868), 1856. Chromolithograph on paper, 18⅝ × 26⅝ in. Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Robert F. Norfleet Jr. Photo: Travis Fullerton, Courtesy Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. |

In 1855, Smithsonian Regent and art collector William Wilson Corcoran traveled to Europe with former president Millard Fillmore. Carrying a letter on Smithsonian letterhead, they met Humboldt in Berlin, where the aging naturalist welcomed them, showing them around the city and arranging for a dinner with the Prussian king. Corcoran commissioned a marble bust of Humboldt; Fillmore returned with this color print showing Humboldt in his library, surrounded by his books, travel diaries, maps, specimens, and artworks. His rooms had come to resemble Peale’s museum. The globe is positioned to show the regions he visited in South and North America.

|

The exhibition also includes the original “Peale Mastodon” skeleton, on loan from the Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt, with ties to Humboldt, Peale, and an emerging American national identity in the early nineteenth century. Its inclusion in the exhibition represents a homecoming for the important fossil that has been in Europe since 1847, and emphasizes that natural history and natural monuments bond Humboldt with the United States. The skeleton, excavated in 1801 in upstate New York, was the most complete to be unearthed at that time. Its discovery became a symbol of civic pride. In 1804, Humboldt was honored with a dinner beneath the mastodon while it was exhibited in the Peale Museum in Philadelphia. Two paintings featuring the fossil—“Exhumation of the Mastodon” (1806–08) and “The Artist in His Museum” (1822) both by Peale—are on display nearby in the galleries.

Alexander von Humboldt and the United States: Art, Nature, and Culture is the first exhibition to examine Humboldt’s impact on five spheres of American cultural development: the visual arts, sciences, literature, politics, and traces how Humboldt’s ideas influenced the transcendentalists and laid the foundations for the Smithsonian, the Sierra Club, and the National Park Service.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|