Alix Aymé Will Be the Focus of a New Documentary Produced by Fletcher/Copenhaver Fine Art

Alix Aymé’s life reads like a movie—a dramatic tale punctuated by war, loss, and the healing power of art. So it was only natural that Joel Fletcher and John Copenhaver of Virginia’s Fletcher/Copenhaver Fine Art decided to create a documentary about Aymé and her fascinating story.

The duo, who formed Fletcher/Copenhaver in Fredericksburg in 1993, discovered Aymé’s work while on a buying trip in France about ten years ago. Fletcher says, “We bought a small and very beautiful watercolor on silk and put it on our website. Shortly after, we were contact by Pascal Lacombe and Guy Ferrer, who were close friends of Alix.” Over the course of the next decade, Fletcher and Copenhaver became immersed in Alix Aymé’s personal and artistic journey. “She was an extraordinary artist and quite famous in her time,” says Fletcher. “But after her death, she was a bit neglected.”

Born in Marseilles in 1894, Aymé studied music and art at the Conservatory of Toulouse. She then moved to Paris, where she studied with Maurice Denis—a leader of the Symbolist movement, who became Aymé’s lifelong mentor and friend. In 1920, Aymé married her first husband—a professor who was on his way to Asia to teach French. The couple settled in Hanoi, where Aymé taught painting. Aymé was so enamored with Indochina, that when her husband decided to return to France, she resisted. Around this time, the French government commissioned Aymé to work on the 1931 Colonial Exposition in Paris. She traveled to Angkor Wat and then to Luang Prabang, Laos, where she became acquainted with the Royal family. The Laotian King Sisavang Vong commissioned Aymé to create a series of murals for the Royal Palace. She agreed, and the murals, which depict everyday life in Luang Prabang, are considered national treasures today.

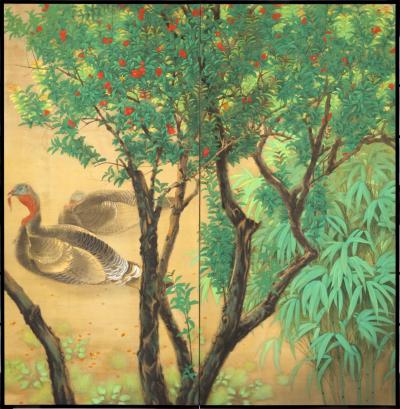

While in Laos, Aymé met her second husband—General Georges Aymé, who later became the Commander of the French Forces in Indochina. Together, they returned to Hanoi and Aymé began teaching lacquer at the Vietnam University of Fine Arts. Fletcher says, “Aymé learned lacquer in the 1920s from a Japanese master. It is an ancient art and, at the time, it was dying out and the techniques were not being passed on to the next generation. Alix not only taught her students how to use lacquer, but how to paint with it, creating art that transcended the merely decorative. She also introduced the use of gold and silver leaf and fragments of duck egg to produce a pure white, techniques that were unknown in the earlier Indochinese tradition. Today, lacquer is thriving in Vietnam and Alix Aymé is really responsible for rescuing that tradition.”

During the early 1940s, unrest in southeast Asia grew and in March of 1945, the Japanese Army took control of Indochina. General Aymé was interned in concentration camps and Alix and her sons—Michel by her first husband, and François by General Aymé—remained in Hanoi under harsh living conditions until the end of the war. “When the war was over, the French felt a wave of euphoria,” says Fletcher. But that was to be short lived. Increasing hostility against French colonials led to a spate of violent riots and in 1945, Aymé’s oldest son, Michel, was murdered. The loss of Michel would haunt Alix for the rest of her life and serve as a source of inspiration for her later art. Two days after Michel’s death, General Aymé was released from the concentration camp and flown back to France. Alix and François, who could not immediately book passage back to Europe, returned to Paris several months later. While caring for her ailing husband and mourning the loss of her eldest son, Aymé found solace in her art.

In 1948, Aymé was approached about creating a commission for the Convent of Our Lady of Fidelity in Normandy. Built in the 1920s, the convent features exquisite decorations created by the celebrated French designer and glassmaker René Lalique. Aymé declined the offer at first, but the nuns persuaded her to create the commission for their Stations of the Cross. It took Aymé a year to finish the fourteen lacquer panels, which were influenced by the celebrated poet, playwright, and diplomat Paul Claudel, and Tsuguharu Foujita, a Japanese artist to whom Aymé became close after the war.

Ultimately, the project helped Aymé come to terms with her own grief. Upon completion of the panels, she wrote a letter to the mother superior that read, “I am very happy to learn that the Stations of the Cross are exactly what you wished them to be. I painted them truly with all my heart, and, in exchange, they have been for me a great comfort. During these several months that I have lived continually with Christ and his Passion, even though the subject is one of great anguish, it has helped me to find a measure of peace in my sorrow. I am grateful to the Community of the Faithful Virgin for having done this for me.” In March 2010, Aymé’s Stations of the Cross panels were designated an historic monument by the French government.

Fletcher and Copenhaver, who are working with the filmmaker Joe Sanford to produce their Aymé documentary, hope to include an interview with the convent’s current mother superior. The film will also include input from a number of collectors as well as some of Aymé’s relatives. Fletcher says, “We hope that viewers will be inspired by the remarkable courage and remarkable art of Alix Aymé. She was a woman with a great soul and a great talent.” Fletcher and Copenhaver hope to have the documentary complete by the end of 2017.

Alix Aymé continued to create art in a range of media, including lacquer works, oil and tempera paintings, watercolors, and prints, until her death at the age of 95.

Click HERE to view the trailer for Fletcher/Copenhaver’s Alix Ayme documentary.