American Folk Pottery: Art and Design

Highlighting nearly fifty objects from its renowned folk art collection, Colonial Williamsburg’s new installation American Folk Pottery: Art and Design, on view in the Elisabeth M. and Joseph M. Handley Gallery at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, March 01, 2020, through December 31, 2022, features iconic objects from the collection and many recently acquired pieces on view for the first time.

Potters are craftspeople; in the past they made vessels out of clay that were functional and designed to meet the needs of their communities. Their work reflects regional styles and traditions passed down through generations; and many modern folk potters draw from that rich legacy to create their wares, be they functional, aesthetic, or both. The early American pottery industry thrived on the manufacture of functional pieces like jugs, storage jars, and cream pots. Although potters designed their wares for everyday use, they chose to decorate their pottery with a variety of simple designs that would appeal to their customers.

Nineteenth-century American pottery maps the migration of people and their traditions from region to region as the United States expanded. Potters from New England took their techniques to Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina. A generation or two later, potters from these same families sought their fortunes further south and west. They moved to Tennessee, Alabama, and Texas, leaving a trail of pottery with similar glazes, shapes, and handle constructions. By the turn of the twentieth century, distinctive American styles of pottery were being produced in almost every state.

Who made it? The answer to this question is frequently unknown or more complicated than it seems. The lives of individual potters are almost always lost to us and this is particularly true in the case of free and enslaved African Americans. The exhibition acknowledges the lives of a few known African-American potters and the many unknown who created countless wares. The stories of women potters are also often unrecorded; and it is likely that many more vessels were created by female potters than are known today. The women potters highlighted in this exhibition were either born or married into potting communities. Like the men who made most of the pots in this exhibition, these women were many times motivated by the need to earn a living. Yet their work also expresses great artistry and skill that is frequently overshadowed by the work of their male counterparts.

|

|

Four-gallon cooler, Somerset Potters Works (active 1847–1882), Somerset, Mass., 1847–1860. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 inches. Colonial Williamsburg Collections, Museum Purchase (1975.900.1). |

In 1847, brothers Benjamin and Clark Chace built a stoneware kiln on their family property in Somerset, Massachusetts, and incorporated as the Somerset Potters Works. The family had made earthenware in Somerset at least as early as 1768. This cooler is distinguished by stamped decoration of birds on branches. Stamped ornamentation is uncommon on stoneware from New England, but is often seen on pottery made in New York State. The Somerset Potters Works’ investment in stamps for this type of embellishment suggests a commitment to decoration on functional wares.

|

|

|

Flowerpot, Enos Smedley (1805–1892), Westtown, Penn., 1825. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 9-3/16 inches. Gift of Beatrix T. Rumford (1983.900.1). |

Incised script beneath the upper scalloped edge of this handsome pot reads “Elizabeth Canby Brandywine 11th MO 21st 1825.” It is extremely rare for a utilitarian object such as a flowerpot to retain a detailed history of ownership and a strong attribution to a specific pottery, but this example bears both. Elizabeth Roberts Canby, the original owner of this flowerpot, married James Canby in 1803. “Brandywine” was the name of their Wilmington, Delaware, home. As of yet, the significance of the 1825 date has not been identified as having an association with the couple. But other flowerpots made by Enos Smedley bear similar dates that seem unassociated with the names on the pots, so it is likely that the date documents the pot’s production, a common practice shared by many potters on both sides of the Atlantic.

|

|  | |

Flower urn, S. Bell & Son (active 1882–1900), Strasburg, Va., 1882–1892. Earthenware, H, 13½ inches. Colonial Williamsburg Collections, Museum Purchase (2008.900.3). | ||

Another spectacular utilitarian form associated with flowers in the exhibition is this flowerpot or urn marked with a stamp indicating it was made at the Bell Pottery while under the ownership of Samuel Bell and his sons at the end of the nineteenth century. The Bell family had created traditional earthenware and stoneware in the Valley of Virginia for generations. Majestic lion mask handles with incised manes on the sides of the piece were made from molds originally used by Solomon Bell earlier in the century. The foliate-like spots and dashes in green slip are also indicative of the Bell Pottery production.

|

|

|

Sixteen-gallon storage jar, Daniel Seagle (1805–1867), Vale, N.C., ca. 1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 19 inches. Colonial Williamsburg Collections, Museum Purchase (2013.900.1). |

Daniel Seagle, maker of this beautifully glazed and abnormally large storage jar, was a potter in the Catawba Valley of North Carolina, with family roots in Pennsylvania and Germany. Tax records reveal that Seagle began his career as an earthenware potter and shifted to alkaline or ash-glazed stoneware production before 1830. He was a master at creating the four-handled storage jar; but only a small number of extraordinarily large vessels like this one survive. His largest known piece is a twenty-gallon jar. Despite their large size, his wares are very thinly potted, unlike most storage jars of the time. Made to hold dry or wet foodstuffs, this monumental example bears a stamped “DS” on one handle and the capacity mark “16” on another. The four-handled form is closely associated with Catawba Valley stoneware and was made into the twentieth century.

|

|

|

Storage jar, Chester Webster (1799–1882), Randolph County, N.C., 1870–1879. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8¼ inches. Colonial Williamsburg Collections Museum Purchase (2008.900.1). |

McCloud Webster’s nephews, Edward and Chester, moved from Connecticut to North Carolina, and continued to produce their family’s traditional stoneware, as seen with the storage jar. Carrying with them the decorative techniques mastered from their family in Connecticut, they incorporated incised decoration of geometric and figural designs into their motifs. This handsome half-gallon storage jar illustrates cross-hatch patterns at the top of the piece and a well-executed bird, fish, and flower shown on the lower half.

|

|

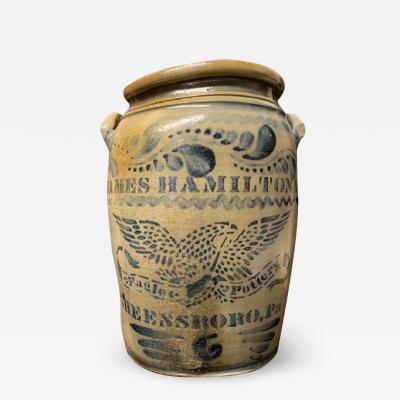

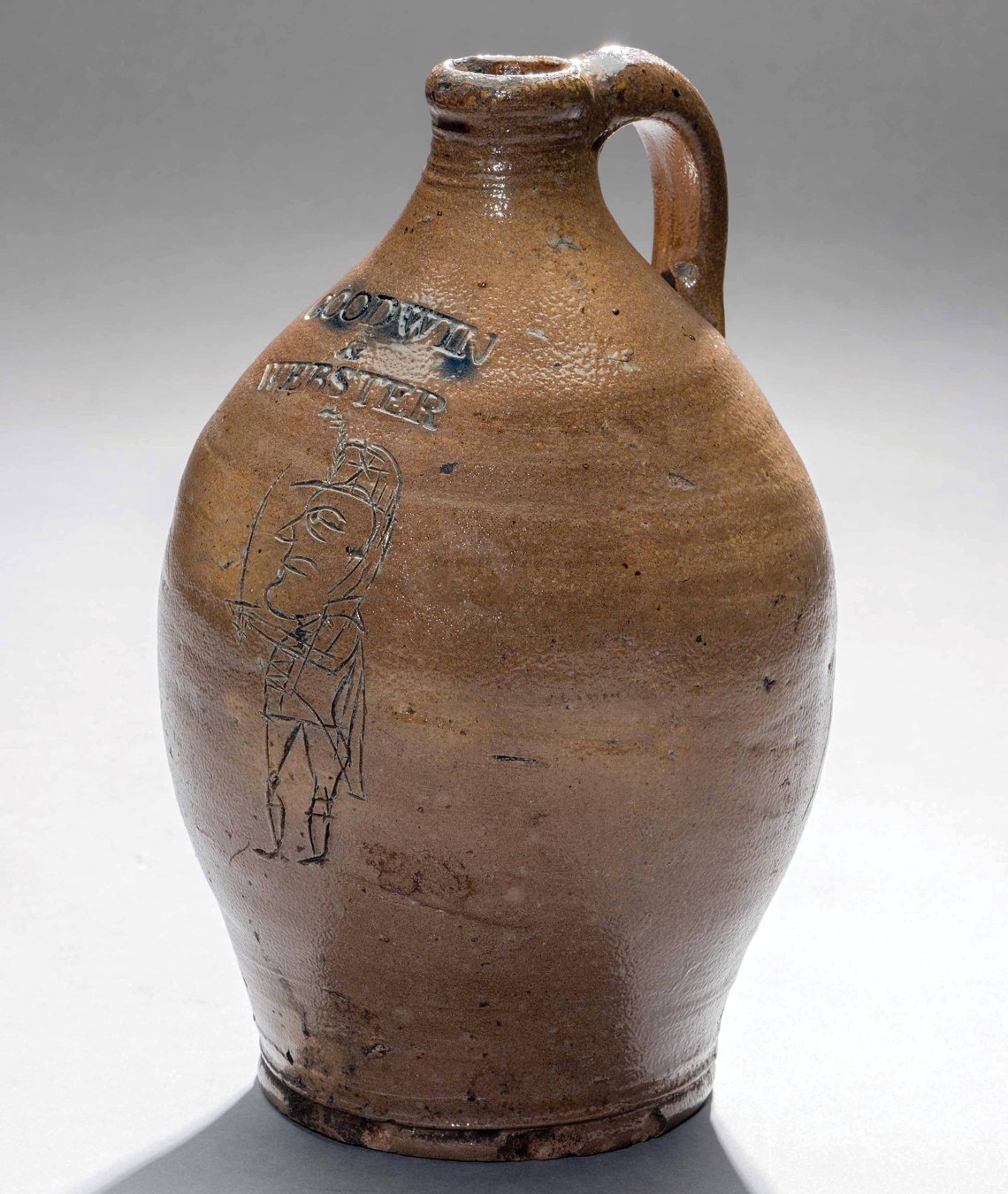

Jug, Goodwin & Webster (active ca. 1810–1840), Hartford, Conn., 1812–1830. Salt-glazed stoneware, H. 16-1⁄16 inches. Colonial Williamsburg Collections, Museum Purchase (1959.900.2). |

Members of the Webster family were employed at several pottery factories in Hartford, Connecticut, where they learned to make salt-glazed stoneware with incised decoration in the English stoneware tradition. This jug with the image of a soldier is typical of the everyday wares produced at the pottery owned by Horace Goodwin and McCloud Webster.

|

|

|  | |

Five-gallon syrup jug, David Drake (1801–ca. 1875), Stoney Bluff plantation, Edgefield, S.C., 1850–1860. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 17 inches. Colonial Williamsburg Collections Museum Purchase (1939-137). | ||

David Drake, an enslaved African-American potter, created ash-glazed stoneware vessels distinguished by their large size and, in some instances, their inscribed verses. Drake is the only known enslaved potter who signed and dated his wares. This action was risky because South Carolina had outlawed literacy among enslaved people. Although this jug is not embellished with poetry, at almost seventeen inches tall and fifteen inches in diameter, it has the scale associated with Drake’s work. Other distinctive features include the impressed thumbprint at the base of each handle and five incised punctates at the neck to indicate its five-gallon capacity. Syrup jugs held fresh molasses, the principal sweetener in the southerner’s diet. Although popular in the South, the form is virtually unknown in other parts of the country.

|

|

Storage jar, attributed to Archibald McPherson (1838–1909), Belcher’s Gap, DeKalb County, Ala., 1865–1885. Alkaline-glazed stoneware, H. 12¼ inches. Colonial Williamsburg Collections Museum Purchase, C. Thomas Hamlin III Fund and Elise Wright in memory of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Clay Hofheimer II and in honor of John C. Austin (2015.900.4). |

The Belcher, McPherson, and Henry families moved to DeKalb County in the Sand Mountain region of Alabama during the 1860s. They began producing utilitarian pottery at several sites within walking distance of each other. These potters were known for a technique called “double-dipping,” where they used two types of alkaline glazes on the same piece of pottery.

|

|  | |

Face jug, Burlon Craig (1914-2002), Vale, N.C., 1979. Ash-glazed stoneware and porcelain. H. 14 inches. Gift of Daisy Wade Bridges (2010.900.2). | ||

Burlon Craig was one of the first twentieth-century potters to revive the face jug tradition. He worked in a traditional manner during a time when many potters were converting to more modern electric kilns and purchasing clay rather than digging it themselves. Before he began making face jugs in the 1970s, Craig limited his production to useful wares. His use of blue slip and white clay for the decoration on this and other face vessels yielded stunning results: the body was covered in a deep blue slip; white clay placed in the eyes liquefied during firing creating streaks of white down the side of the pot as though the face is crying. The teeth are actually made of porcelain and show Craig’s ability to combine and manipulate different clay bodies in the same kiln. This spectacular piece is one of Craig’s earliest face jugs.

|

|  | |

Jardinière, Michael Crocker (b. 1956), Melvin Crocker (b. 1959), and Pauline Crocker (dates?); Lula, Hall, and Banks Counties, Ga., 1997. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 35⅜ inches. Gift of Daisy Wade Bridges (2010.900.3). | ||

Unlike many contemporary potters, the Crockers of Georgia work only with local clays and handmade glazes. These traditional practices link them directly to the history of Georgia folk pottery. This jardinière or plant stand was crafted by several members of the Crocker family, each one lending his/her specialization to the object: Michael threw the body of the vessel, his brother Melvin sculpted the snakes, and their mother, Pauline, modeled the flowers. The result is a cohesive object that not only represents the skills of each potter, but also blends their talents to create an object with near lifelike features, from the venomous fangs and shimmering scales of the snake that entwines itself around the pedestal, to the petals of vining flowers.

|

|  | |

Snake jug, Anna Pottery (1859–1896), Anna, Ill., ca. 1865. Salt-glazed stoneware. Museum purchase, partial gift of Mr. & Mrs. Milton Schaible (1976.900.5). | ||

This jug, with its cold painted writhing snakes, frogs, dung beetles, and human figures crawling in and out, has often been mistaken for a piece of visual propaganda in support of the nineteenth-century social temperance movement against alcohol consumption. However, Cornwall and Wallace Kirkpatrick, owners of the Anna Pottery, where this jug was made, were known non- supporters of temperance and recent scholarship suggests that the Anna Pottery snake jugs were actually social and political statements against what the Kirkpatricks regarded as late-nineteenth century Victorian prejudices. In fact, Cornwall spoke out against temperance during political speeches. Wallace served a six-month term with a local temperance group, but he was considered an embarrassment to that organization when his true views on the subject were revealed. This jug and others like it were actually meant to be ironic; a playfully cynical commentary on drinking and the temperance movement.

|

|  | |

| Elvis, Georgia Blizzard (1919–2002), Chilhowie, Smyth County, Va., 1998. Earthenware. H. 10½ inches. Gift of Folk Art Society of America (2001.900.1). | ||

Georgia Blizzard began her pottery career in 1958 when she began selling low-fired earthenware pots through a neighbor who had contacts in the art world. Illness had led to the loss of her job at a textile mill, her husband had died, and she was left to support her sister and daughter. As a child in rural southwestern Virginia, Georgia and her sister, May, had fashioned objects from clay they dug out of creek beds. As an adult, much of Georgia’s work was glazed using found materials including leaves, dried dung, rubber scraps, and coal. Potting was a very personal expression for Blizzard, and she stated in an interview: “I can get rid of taunting, unknowing things by bringing them out where I can see them . . .I feel the need to do it. It’s all I have left.”

|

|

Jar, Katherine (Kathy) Pino (b. 1935), Zia Pueblo, N.Mex., ca. 1970. Earthenware. H. 6 inches. Colonial Williamsburg Collections, Museum Purchase (2019.900.2). |

The people of the Zia Pueblo have a strong pottery tradition dating back to the nineteenth century. Katherine Pino, maker of this jar, is a member of a well-known Zia potting family. Today, she and other family members continue to manufacture traditional Zia pottery. This matte-painted jar features a large stylized roadrunner created with the same slip-and-painting technique used by her ancestors.

|

All of the objects in this new exhibition are a celebration of American pottery in their form, function, and whimsical flourishes. Their stories reveal regional, ethnic, and gender diversity in the wares made by potters across the United States, from Massachusetts to New Mexico.

Angelika R. Kuettner is the associate curator of ceramics and glass, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia. Suzanne Findlen Hood is a former curator of ceramics and glass, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Photography by Jason B. Copes.

This article was originally published in the 20th Anniversary (Spring/Summer 2020) issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.