An American Journey: The Art of John Sloan

| |

| Fig. 1: John Sloan (1871–1951), Self-Portrait, 1890. Oil on window shade, 14 × 11⅞ inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1970. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

On February 3, 1908, an exhibition opened to great fanfare at Macbeth Galleries in New York. The day before the opening, the New York Herald trumpeted “Secession in Art,” and the World’s lengthy headline announced: “New York’s Art War and the Eight Rebels Who Dared to Paint Pictures of New York Life (instead of Europe) and are Holding Their Rebellious Exhibition All by Themselves.” In the coming weeks, the Philadelphia Press, the New York Times, American Art News,Current Literature, and The Craftsman covered the exhibition in detail. It was an impressive display of interest for an exhibition of paintings by artists who regularly exhibited in the city.

Through their own promotional efforts, the painters—John Sloan, Robert Henri, William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, and Maurice Prendergast—had become known as “The Eight” months before, though they were not an organized faction, and 1908 was the only occasion when they exhibited as a group. The artists varied in accomplishment, and painted diverse subjects in dissimilar styles. One reviewer compared the show to “the jangling and booming of eight differently tuned orchestras.” 1

What the painters shared was a sense of frustration with academic art and the institutions that served it, particularly the National Academy of Design in New York. The exhibition was intended to register their protest. This narrative of artistic rebellion, seized by the popular press and, later, by art historians, became a watershed in American art, uniting and defining this disparate set of artists.

|

| Fig. 2: John Sloan (1871–1951), Schuylkill River, 1900-1902. Oil on canvas, 24 × 32 inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of the John Sloan Trust, 2006. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

| |

| Fig. 3: John Sloan (1871–1951), Violinist, Will Bradner, 1903, Oil on canvas, 37 × 37 inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1970. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. | |

| |

| Fig. 4: John Sloan (1871–1951), Throbbing Fountain, Night, 1908. Oil on canvas, 32⅛ × 26⅛ inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of the John Sloan Memorial Foundation, 1997. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

When the exhibition of The Eight opened, Sloan had been living in New York for less than four years and painting seriously for only about a decade. Born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, Sloan was raised in Philadelphia. Although not from an affluent family, Sloan grew up in a house filled with books and prints, watercolors and oil paints, and parents who encouraged his creativity. Working from A Manual of Oil Painting by John Collier, Sloan taught himself the basics of oil painting when he was around nineteen years old. Late in life he recalled this early foray: “My first serious oil painting was a self-portrait . . . It is a very earnest, plain piece of work; shows no facility or brilliance. The work of a plodder.” 2 In the painting (Fig. 1), a serious young man in a dark coat and tie emerges from the dark background: his pose is resolutely frontal and his expression is bland. The most memorable element may be his gold-framed eyeglasses. And though the artist’s mature assessment may be unduly harsh, “earnest” does seem the ideal descriptor for the small canvas and its young maker.

Sloan left Central High School early to help support his family and soon found work as a newspaper illustrator for the Philadelphia Inquirer, and later, the Philadelphia Press. He took classes at the Spring Garden Institute and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and developed friendships with the young artists and illustrators of the city, who often gathered in Robert Henri’s studio at 806 Walnut Street. Henri encouraged the assembled group—which sometimes included fellow newspaper illustrators Glackens, Luks, and Shinn—to begin painting seriously and to see themselves as artists.

Henri encouraged these emerging artists to paint the world around them, and by the late 1890s, Sloan was heeding his friend’s advice. Sloan painted Philadelphia from Walnut Street to the Schuylkill in canvasses that focus on architecture and atmosphere (Fig. 2). His portraits generally depict individuals in the artist’s immediate circle; one of Sloan’s finest early paintings, Violinist, Will Bradner (1903, Fig. 3), portrays a friend who was the first violinist of the Philadelphia Symphony Society. In city scenes and portraits, Sloan employed a dark and muted palette brightened only by flesh tones, highlights of white and yellow, and dabs of orange and red. His color choices reflect the direct influence of Henri and their shared admiration for historical and modern masters, including Frans Hals, Diego Velázquez, Édouard Manet, and J. A. M. Whistler.

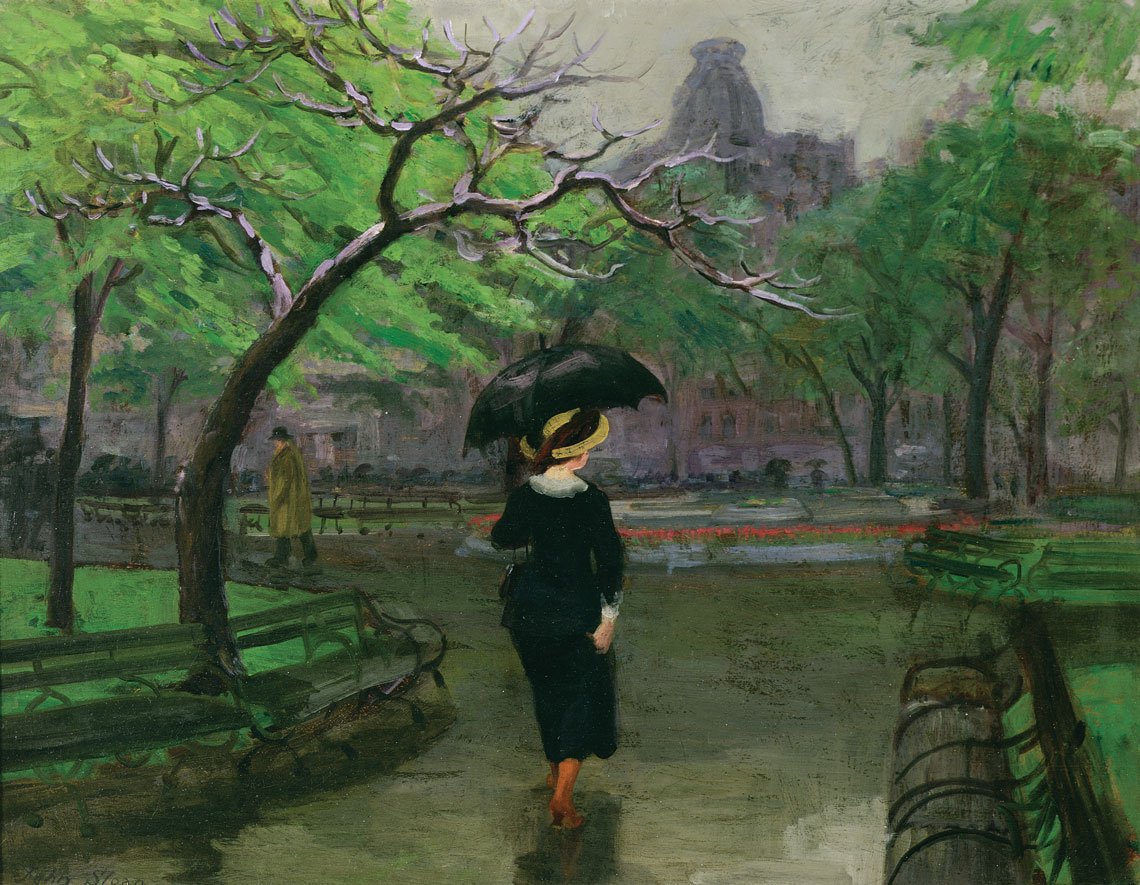

In 1904 Sloan and his wife Dolly relocated to New York, where Sloan supported himself as a freelance illustrator for books and magazines, while he explored his new city and built his career as an exhibiting artist. They settled near Madison Square, in a neighborhood that offered rich subjects for etchings and paintings like Throbbing Fountain, Night (1908, Fig. 4). A few years after his move, Sloan was exhibiting his portraits and city pictures in exhibitions around the nation, including the annual juried shows at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Sloan was developing a reputation as a painter of New York subjects, a distinction that was cemented with the well-publicized exhibition of The Eight, where Sloan showed seven paintings of urban life.

|

| Fig. 5: John Sloan (1871–1951), Spring Rain, 1912. Oil on canvas, 20¼ × 26¼ inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of John Sloan Memorial Foundation, 1986. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

|

| Fig. 6: John Sloan (1871–1951), Coytesville on the Palisades, 1908. Oil on linen mounted on board, 8¾ × 10⅞ inches. Delaware Art Museum; Special Purchase Fund, 1960. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

| |

| Fig. 7: John Sloan’s Sketch Box and Oil Paints, ca. 1906. Wooden box with palette and oil paints, 9¾ x 13 x 3 inches. John Sloan Manuscript Collection, Helen Farr Sloan Library and Archives, Delaware Art Museum. |

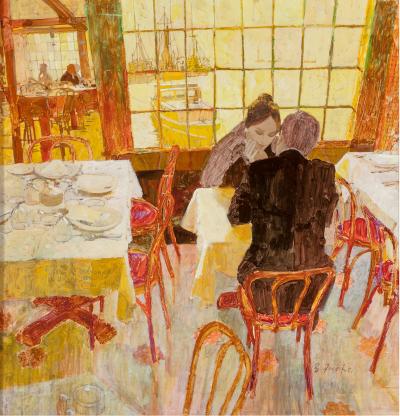

An inveterate walker, Sloan found inspiration all over Lower Manhattan. His painting Spring Rain (1912, Fig. 5) pictures a gray day in Union Square. In the same year he painted this canvas, Sloan relocated to Greenwich Village, joining the growing community of artists and intellectuals in that neighborhood. Summers took the painter further afield, and Sloan began plein air painting on visits to Bayonne and Coytesville, New Jersey (Fig. 6), and Fort Washington, Pennsylvania. He outfitted a small sketch box for outdoor work and produced dozens of small landscapes each summer (Fig. 7).

Painting outside brightened Sloan’s palette, but it was his adoption of the Maratta method that radically shifted his approach to color. In 1909 Sloan was introduced to the color system, diagrams, and premixed paints created by the artist Hardesty Maratta. When he painted Spring Rain, Sloan was working with Maratta’s system, which associated particular colors with specific musical notes and instructed painters to organize their palettes based on harmonious chords of color. The painting was based on a dominant seventh chord featuring blue-green, red-purple, orange, and yellow-green, hues that align with the notes G, B, D, and F. This structured approach to color was one of many color theories in vogue in the early twentieth century, and it attracted adherents among Sloan’s circle, including Robert Henri and George Bellows. Toward the end of 1912, Sloan wrote to art collector John Quinn that he had felt “the breeze of brighter color which is sweeping the fields of art.” 3

| |

| Fig. 8: John Sloan (1871–1951), Henrietta Mayer, White Skin, 1913. Oil on canvas, 24 × 20 inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of the John Sloan Trust, 2006. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. | |

| |

| Fig. 9: John Sloan (1871–1951), Long Shadows, 1918. Oil on canvas, 20 × 26 inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of the John Sloan Trust, 2006. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

In February of 1913, the International Exhibition of Modern Art, better known as the Armory Show, introduced the latest in modern art to a broad American audience. Critics and visitors to the show were captivated and confused by European postimpressionist paintings by Cézanne, Matisse, and Van Gogh, and cubist compositions by Picasso and Duchamp. Before the Armory Show, Sloan certainly had been aware of the wide range of modern art exhibited in New York, but the exhibition seems to have left its mark; his paintings soon began to vibrate with high-keyed color and rhythmic brushwork (Fig. 8).

Between 1914 and 1918, Sloan and his wife spent summers in Gloucester, Massachusetts, with artist friends, including Charles and Alice Winter and Randall Davey, who were also experimenting with the Maratta color system. Sloan committed himself to painting in oils daily when in Gloucester. Most of the resulting pictures were landscapes painted outdoors and marked by saturated colors and patterned brushwork that may derive from the Van Gogh paintings Sloan encountered at the Armory Show (Fig. 9). Sloan’s summers in Gloucester were immensely productive; in the course of five seasons, he painted 292 paintings, nearly one quarter of his career output. These canvasses include some of the artist’s most daring compositions.

Back in New York, Sloan commenced teaching at the Art Students League in 1916. The League brought new ideas and new friends into his circle, and Sloan began to focus more seriously on figure painting, “to keep a little ahead of my students.” 4 These students included Guy Pène du Bois, Isabel Bishop, and Reginald Marsh, who would become known for their urban realist paintings in the 1920s and 1930s. While his students turned to city subjects, Sloan increasingly painted portraits and nudes during his months in New York each year (Fig. 10).

In 1919, with Henri’s recommendation, the Sloans traveled to Santa Fe, New Mexico, for the summer. The new surroundings delighted the artist. The Sloans purchased a home in Santa Fe in 1920, and returned almost every summer thereafter. In New Mexico, Sloan depicted everyday life in town, landscapes, and Pueblo dances (Fig. 11). For his Santa Fe town scenes, Sloan worked much as he did in New York, painting local subjects from memory in his studio. Landscape paintings might be made on the spot or worked up in the studio from sketches. His images of Pueblo dances relied on memory, as sketching and photography were forbidden at ceremonial dances.

|

| Fig. 10: John Sloan (1871–1951), Blonde Nude with Orange, Blue Couch, ca. 1917. Oil on canvas, 20 × 24 inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of the John Sloan Trust, 2006. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

|  | |

| Fig. 11: John Sloan (1871–1951), Dance at Cochiti Pueblo, New Mexico, 1922. Oil on canvas, 22¼ x 30¼ inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of the John Sloan Memorial Foundation, 1997. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. | Fig. 12: John Sloan (1871–1951), Procession to the Cross of the Martyrs, 1930. Gum arabic tempera underpaint; oil varnish glaze on panel, 24 × 32 inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of the John Sloan Memorial Foundation, 1997. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

| |

| Fig. 13: John Sloan (1871–1951), Self-Portrait, Pipe and Brown Jacket, 1946. Casein tempera underpaint with oil-varnish glaze on panel, 16 × 12⅛ inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1986. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. | |

| |

| Fig. 14: John Sloan (1871–1951), Girl’s Eye View, 1945. Oil on Masonite™, 16 × 20 inches. Delaware Art Museum; Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1980. © 2017 Delaware Art Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

The late 1920s marked a significant shift in Sloan’s painting, when he adopted a new technique in an effort to separate form and color. After 1928, Sloan delineated the major elements of his compositions in tempera on panel, and then built up color with layers of translucent oil glazes. This was a radical departure from the direct alla prima approach to painting that he had employed for the first three decades of his career. Sloan’s new method yielded extraordinary results, like the glowing flames that punctuate Procession to the Cross of the Martyrs (1930, Fig. 12). Sloan used this exacting technique primarily for portraits and figure paintings, the main categories of his late work (Fig. 13). The artist’s second wife, Helen Farr Sloan, was the sitter for some of the finest of Sloan’s paintings after their marriage in 1944 (Fig. 14).

An American Journey: The Art of John Sloan is the first major retrospective of John Sloan’s work since 1988. It explores all facets of the artist’s long career: his work as an illustrator in Philadelphia, his famous depictions of New York City, his portraits, his nudes, his lively views of Gloucester, Massachusetts, and his fascinating studies of Santa Fe, New Mexico. The exhibition includes nearly one hundred works—drawings, prints, and paintings—produced between 1890 and 1946. The Delaware Art Museum holds the largest collection of work by the artist, as well as a rich trove of archival materials donated to the museum by the artist’s widow Helen Farr Sloan.

An American Journey is on view at the Delaware Art Museum through January 28, 2018. For information, visit www.delart.org.

—

Heather Campbell Coyle is chief curator and curator of American art at the Delaware Art Museum.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

—

1. Macbeth Gallery Scrapbook 3, 1902–1910, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

2. Quoted in Rowland Elzea, John Sloan’s Oil Paintings: A Catalogue Raisonné (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1991), 41.

3. Sloan to Quinn, November 12, 1912. Quoted in Grant Holcomb, “John Sloan in Santa Fe,” American Art Journal (May 1978), 34.

4. Elzea, 215.