Andrew Wyeth: Helga on Paper

Andrew Wyeth once described Helga Testorf as an image he couldn’t get out of his mind. The 89-year-old artist is still often driven by what he calls the “white heat of inspiration.” But in those early years of getting to know his then 31-year-old German neighbor—the future subject of what would come to be called the Helga pictures—he sensed that the creative process would evolve over time.

Wyeth was 53 and at work on the painting Evening at Kuerner’s when he first encountered Helga, who was caring for Karl Kuerner. The artist, who is part German, part Swiss, was intrigued by Helga’s Germanic character and outlook. He realized that Helga had sustaining power. She was also a figure of his imagination; the source of his “fifteen-year reverie,” as Wyeth’s biographer later called her. From 1971 to 1985, Helga was Wyeth’s secret muse. He created nearly 240 images of her, showing them to no one and storing them in an unheated attic room at Kuerner’s house.

Andrew Wyeth: Helga on Paper—the first exhibition of Helga works in New York—is on view at Adelson Galleries from November 3 through December 22, 2006. The show comprises sixty drawings, watercolors, and drybrushes. The works in the exhibit were selected from the Helga collection recently sold to an unnamed American for an undisclosed amount by the Japanese collector who owned it since 1989. The gallery chose to focus on the works on paper because, as president Warren Adelson noted, “Andrew Wyeth’s draughtsmanship may be his least heralded virtue, and I feel it may be his greatest.”

The entire Helga suite tends to be remembered for its highly detailed nudes, particularly the image of Helga wearing a black ribbon around her neck, which is often compared to Manet’s Olympia. The Adelson exhibit offers a broad view of the suite and includes First Drawing (Fig. 1), a 1971 head portrait of Helga, so named because Wyeth considered it to be his first successful treatment of his subject. It also features the last work in the Helga series, Refuge (Fig. 2), a 1985 drybrush painting that shows Helga at a time when she was undergoing treatment for depression. Wyeth called it a view of “a woman pulling away from life.” Each of Wyeth’s Helga images stands alone as emotionally powerful works of art.

Wyeth, who is often described as an artistic loner and difficult to categorize, may be best known for his exacting egg tempera technique. At least, his most famous works and those that have commanded the highest prices have been in that medium. In May of 2005, for instance, Sotheby’s sold a 1987 tempera, Battle Ensign, for $3.8 million, more than double its estimate of $1.5 million.

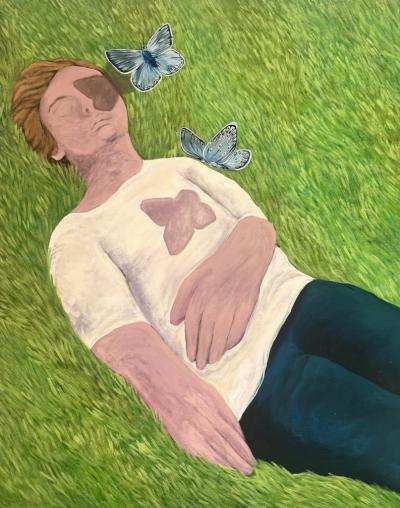

Still, it is the secrecy of the Helga images and Wyeth’s prolonged study of his model—there were thirty-five drawings and watercolors alone investigating the poses of Helga asleep—has remained in the public’s imagination. In a 1993 interview I had with Wyeth prior to the first showing of the Helga paintings in his native Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, Wyeth remarked: “I just put them away. Sometimes, I just let them fall to the floor, and I would walk all over them, or I let my dog trample over them. One time, I even ripped a picture in half. The [Brandywine River] museum put that one together again.”

Fortunately, there was nothing to repair for Andrew Wyeth: Helga on Paper. It features something from nearly all the major groupings in the Helga pictures—the sleep portraits, the nudes, the figures in the landscape. There is also a number of recto-versos and seemingly incomplete works; partial drawings and watercolors that cover only a small part of the paper surface, a typical Wyeth approach. These might be mistaken for preliminary studies if their closely observed details—the shape of Helga’s elbows, for instance—did not transform them into interesting, even eccentric pictures. Adelson’s interest in featuring the seemingly “false starts” and unfinished works is rare among gallery owners. “To me, it’s exciting to show works that are unexpected and inconclusive. And how often do you get to see an artist working out specific problems in his head?”

Wyeth’s breathtaking draftsmanship is evident in works such as the drawings for Overflow (Fig. 3) (named for the water released from the Kuerner’s pond not shown in the black window frame above Helga’s body). Visitors to the exhibit can also admire his dry brush technique (“he owns it—he reinvented the technique,” Adelson says), noticing, for example, Wyeth’s genius for taking risks with the medium, such as texturing Helga’s hair in Pageboy (Fig. 4) or painting the speckled boulders in Knapsack (Fig. 5). Also evident is how, in work after work, Helga appears to travel through space, transcending time. She is shown, standing stock-still, her stiff loden coat casting shadows in the watercolor In the Orchard (Fig. 6). In a study that shows her back to the viewer she appears to be moving confidently forward into the unknown (Fig. 7).

Wyeth is fond of saying that he strives to feel “invisible” when he paints. It is an approach he learned from his father, the illustrator N. C. Wyeth (1882–1945), whose advice to his son was: “Never paint the material of the sleeve. Become the sleeve.” Yet with the Helga paintings, Wyeth often stood back and let his model become the medium. Her willingness to fully take part in the painting process (“She was the one model who always asked, ‘Why are you quitting?’” Wyeth said recently) perfectly suited his artistic temperament.

Visitors who find themselves merely looking for common threads throughout the works in the exhibit may find it more rewarding to ask why the artist chose one medium over another, or what he was looking for in each new position he depicted in drawings for Overflow. This nude, in particular, points to Wyeth’s years of studying what he calls the “bones of a landscape” and his unparalleled mastery among contemporary watercolor painters in using the white of the paper to unusual effects. In one image, Helga’s figure is shown on its side, her hip like a steep mountain range. She appears in a pool of darkness, her body pulled from the untouched white of the paper. Technique aside, Wyeth’s great ability to animate his work with memory and emotion is seen in these drawings.

For Wyeth, drawing is more than a working process to discover a shape or tone of a subject. It is a way of working out a composition—a kind of circling in and exposing a subject from all angles—in order to capture scenes that convey what art historian Henry Adams, an authority on Wyeth’s drawings, has described as a “compressed life experience.” Wyeth’s habit of focusing on certain elements rather than filling an entire page (Fig. 8) has resulted in what Adams describes as images that seem “to emerge magically from the empty white background, rather like a photograph that we observe in the process of development.” Most artists describe too much, according to Adams. “In general Wyeth’s technique is rather simple,” he said in a recent phone interview. “I find it fascinating that while he may occasionally use a lithographer’s crayon or a dark-toned pencil, he usually uses a No. 2 pencil that every school kid would use.”

The “heavily-hyped Helga,” was how the writer John Updike described the collections’ controversial debut in 1987. The exhibit at the National Gallery of Art in Washington drew attention to the model and diminished what some critics considered an unprecedented study of a single subject by an American artist. Andrew Wyeth: Helga on Paper attempts to return the attention to Wyeth. “The dominating theme of all these works is a portrait of an artist,” says Adelson. “This is about his history, his vision. It’s a show about what he makes of her, not what she is.”

Andrew Wyeth: Helga on Paper is accompanied by a hardbound publication of the same name. It features an essay by Thomas Hoving based on personal interviews with both Wyeth and Helga, no longer Wyeth’s primary model but still a nearly daily companion as his nurse and caretaker. For information about the exhibition or publication visit www.adelsongalleries.com, or call 212.439.6800.

-----

Catherine Quillman is a freelance writer and former journalist at the Philadelphia Inquirer. She specializes in the art and culture of the Brandywine Valley.

All images ©Pacific Sun Trading Company.