Ansel Adams: In Our time

For more than fifty years, Ansel Adams (1902–1984) captured the breathtaking beauty of the country’s natural landscape in stunning black-and-white photographs. Adams’ images of the western United States helped define a twentieth-century vision of the American landscape. He pushed the boundaries of fine art photography, employing direct exposure and innovative printing techniques to create vibrant and detailed images. While his career spanned much of the twentieth century, the exhibition, Ansel Adams in Our Time, aims to set him squarely in our time. Adams’ deep connection to the natural environment resonates in new ways today, as the landscapes around us continue to change and be changed.

The exhibition features more than 100 works by Adams alongside photographs by his predecessors and twenty-four contemporary artists, inviting new considerations of Ansel Adams’ continued impact. >>>

|

|

Ansel Adams (1902–1984), Self-Portrait, Monument Valley, Utah, 1958. Photograph, gelatin silver print. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Lane Collection. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

This self-portrait depicts Adams, light meter in hand, standing next to his large-format camera and tripod. He made this image of his shadow falling across a fissured rock face while in Monument Valley, Arizona.

|

|

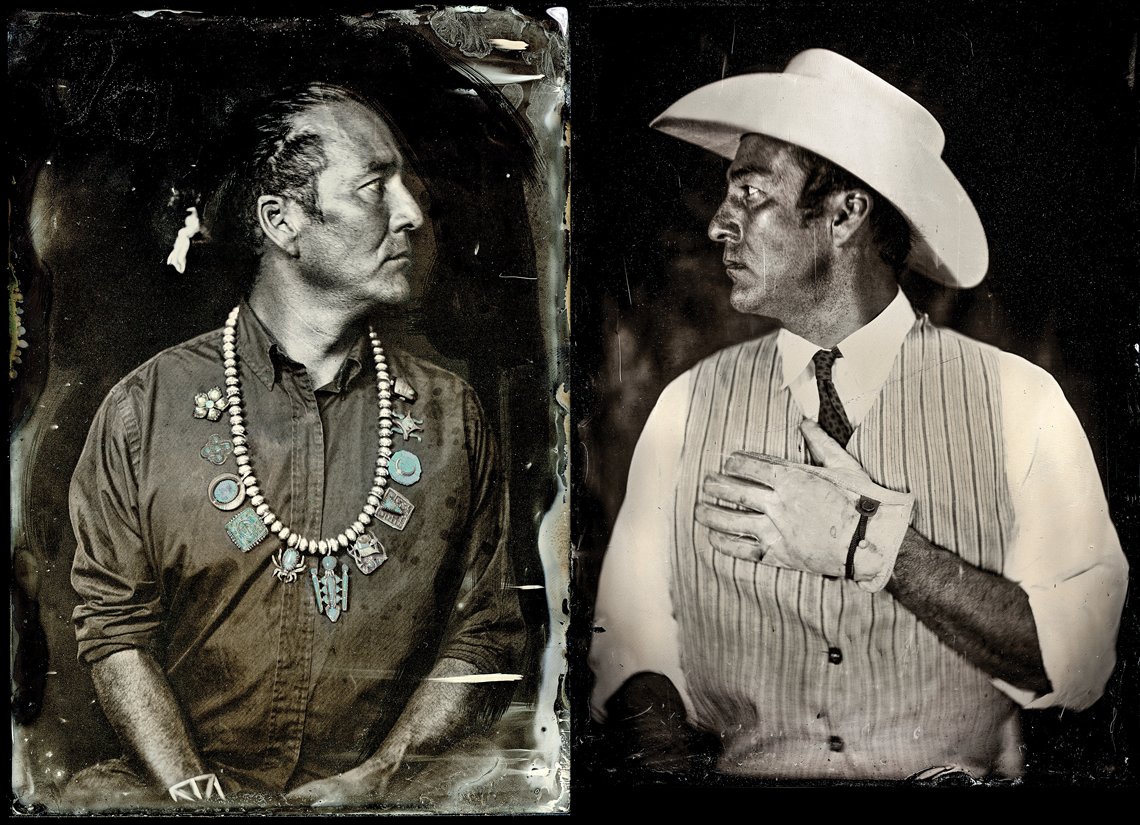

Will Wilson (Diné [Navajo], b. 1969), How the West is One, 2014. Inkjet print. Courtesy of the artist. © Will Wilson. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

Diné photographer Will Wilson created this double self-portrait from digital copies of original tintypes. The work shows Wilson in profile, facing off against himself: on one side wearing a silver and turquoise necklace, and on the other a cowboy hat. Wilson’s dual portrait illustrates the different ways that he—as a Native American artist—might be portrayed and perceived by others, suggesting his identity lies somewhere between the two.

The title riffs on the 1962 John Ford movie How the West Was Won, a western that helped solidify the trope of cowboys and Indians into potent but stereotyped characters for the American public.

|

|

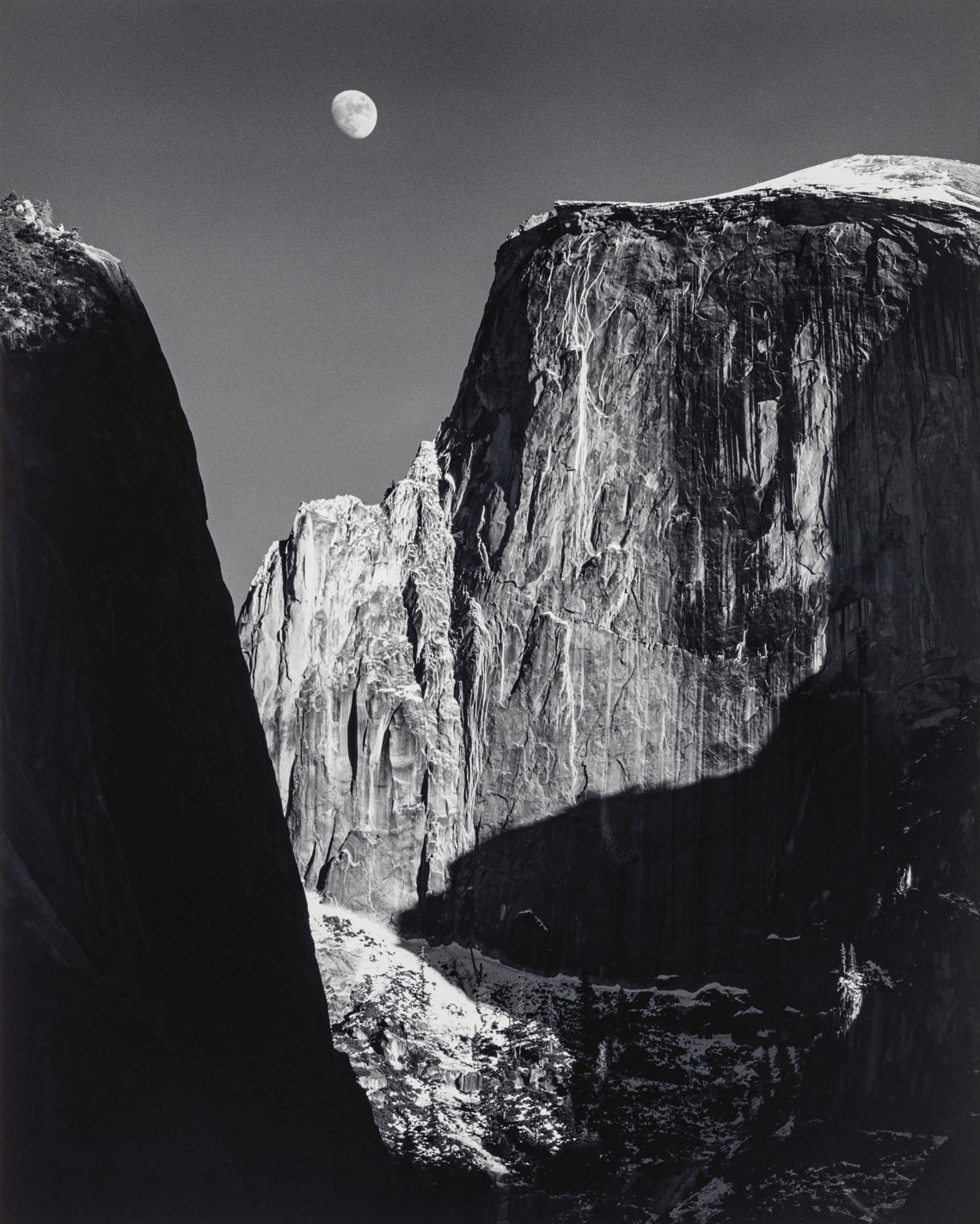

Ansel Adams (1902–1984), Moon and Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, 1960. Photograph, gelatin silver print. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Lane Collection. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

Adams made this striking image of two of his favorite subjects—Half Dome and the moon—on an autumn afternoon in 1960. He witnessed a brilliant nearly full moon rising to the left of the vertical rock face and, using a long lens and orange filter, carefully framed what would become one of his most popular late works.

|

|

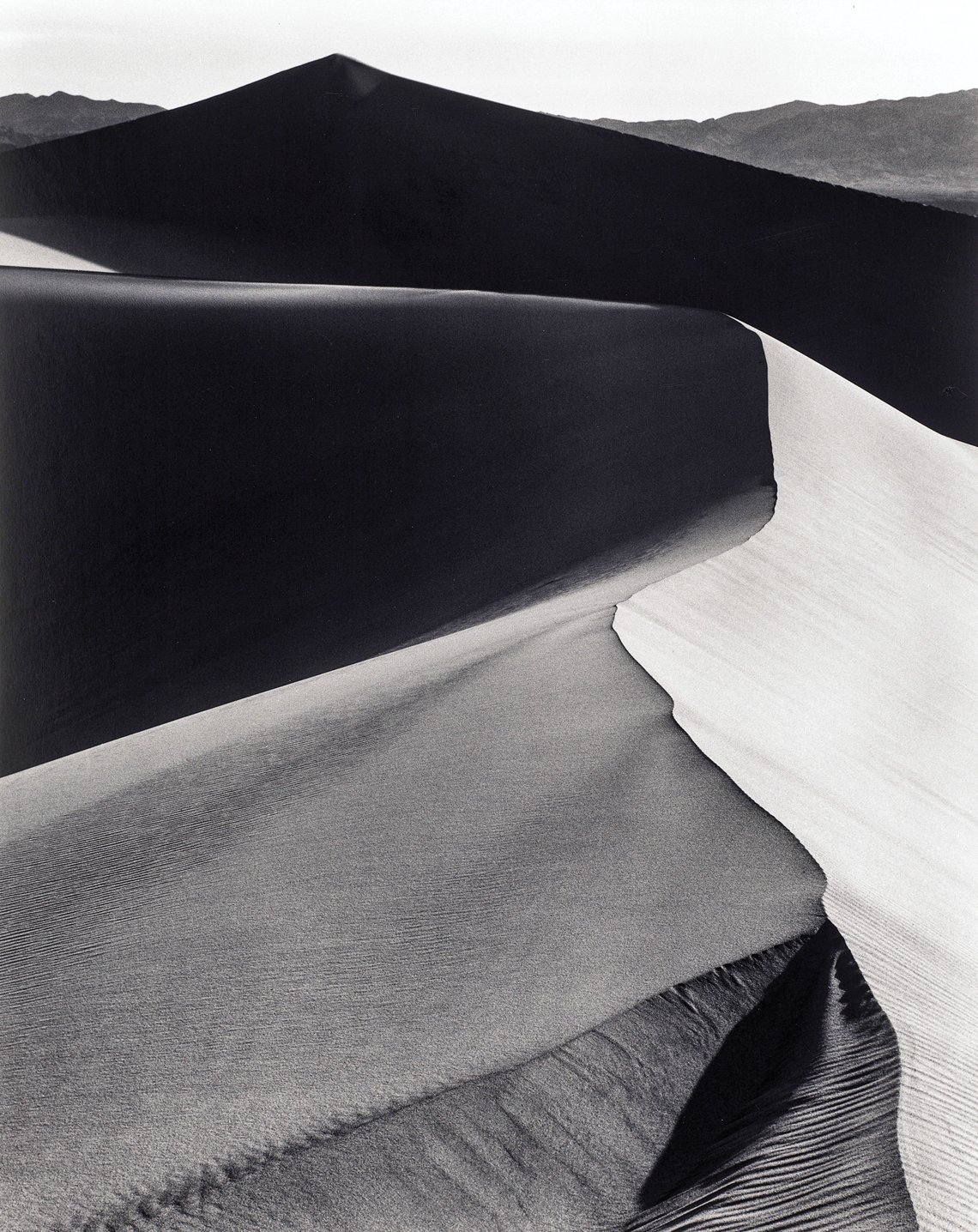

Ansel Adams (1902–1984), Sand Dunes, Sunrise, Death Valley National Monument, California, negative date, circa 1948. Photograph, gelatin silver print. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Lane Collection. © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

Adams initially found the desolate expanse of Death Valley to be a challenging subject. He detailed the making of this image years later in a book: “After sleeping on the camera platform atop my car, I woke before dawn…perched my camera and tripod across my shoulders and plodded heavily through the shifting sand dunes, attempting to find just the right light upon just the right dune…. Just then, almost magically, I saw an image become substance: the light of sunrise traced a perfect line down a dune that alternately glowed with the light and receded in shadow.”

|

|

Laura McPhee (b. 1958), Midsummer (Lupine and Fireweed), 2008. Photograph, inkjet print. Courtesy of the artist. © Laura McPhee. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

Working with a large-format camera, Laura McPhee records the impact of human activity on the land, especially in Idaho, a state she loves and visits regularly. This photograph, along with Early Spring (Peeling Bark in Rain), not illustrated, from her Guardians of Solitude series were made in the aftermath of a massive forest fire. Caused by human error, it devastated thousands of acres of woodland before it was finally extinguished. She returned to the area that summer and saw that it had burst into bloom. In the renewal of the charred landscape, she found a powerful metaphor for human resilience in the face of terrible personal loss.

|

|

Abelardo Morell (American [born in Cuba], b. 1948), Tent-Camera Image on Ground: View of Mount Moran and the Snake River from Oxbow Bend, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, 2011. Photograph inkjet print. Abelardo Morrell | Courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

While growing up in Cuba, Abelardo Morell fell in love with the popular Hollywood westerns playing at the local cinema. Once he immigrated to the United States, he was eager to discover the region for himself. Here he takes in the sweeping grandeur of snowcapped Mount Moran and the Snake River from a vantage point similar to the one employed by Ansel Adams seventy years earlier for his photograph of Grand Teton National Park (illustrated in this article).

Early in his career, Morell began experimenting with the camera obscura (from the Latin for “dark room”), a set-up that allowed him to photograph the view outside, projected through a small hole (or lens) and inverted on the opposite wall of an interior space. More recently, Morell has adapted this technology—using a tent fitted with a periscope and angled mirror—with a digital camera pointed downward to capture the landscape reflected on the ground. This process of combining the distant view with the more mundane ground underfoot allows Morell to turn the terrain into his “canvas” and transform familiar scenes into otherworldly images.

|

|

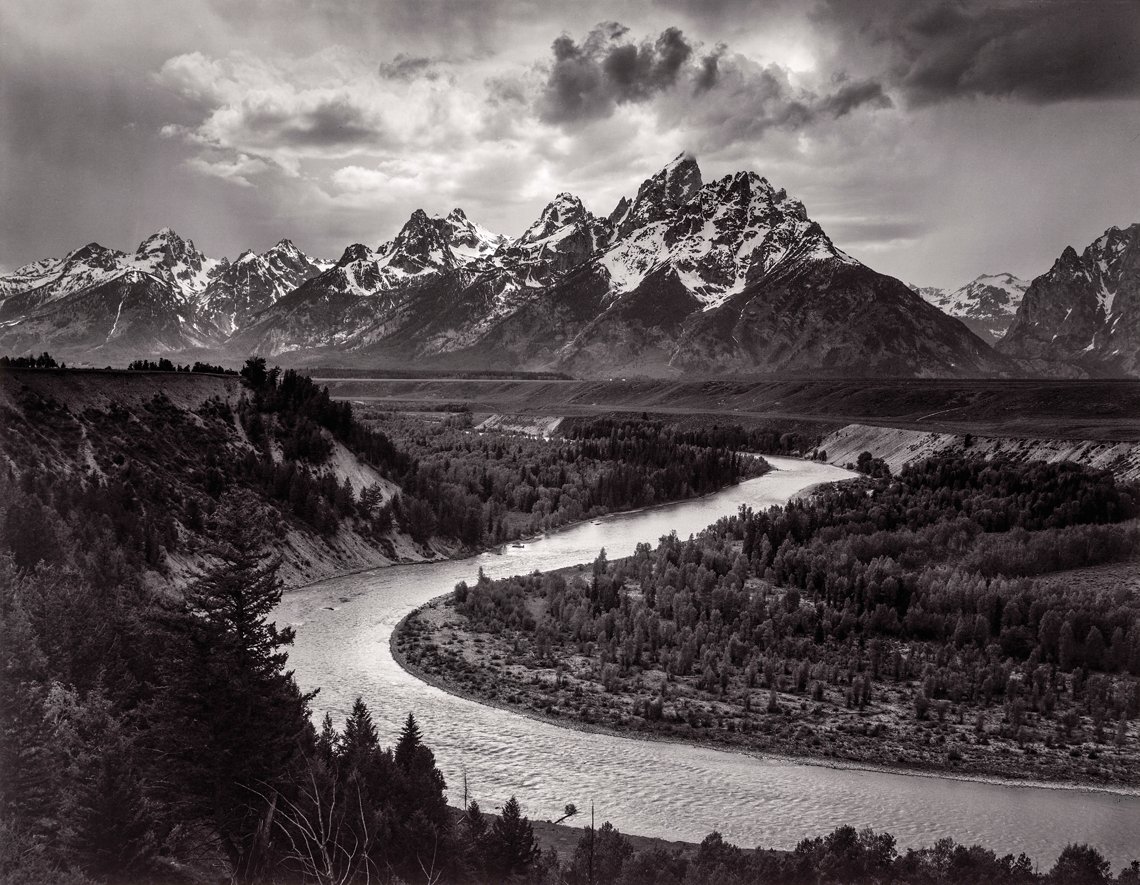

Ansel Adams (1902–1984), The Tetons and Snake River, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming, 1942. Photograph, gelatin silver print. Museum of Fine Arts Boston, The Lane Collection (2018.2733). © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

Taken while traveling for the Department of the Interior’s mural project, this work remains one of Adams’ most famous photographs. Capturing the staggering mountains in the background and the glistening bend of the Snake River, Adams’ sunset shot brings together incredible depth of field with a full range of tones from the darkest black to brightest white.

While Adams’ trek to this spot was laborious, today’s visitors will find a more easily accessible overlook that closely approximates Adams’ vantage point. However, in the decades since Adams’ photograph, the trees have grown taller obscuring the full bend of the river, a gentle reminder that his photo is truly a record of a moment in time.

|

Ansel Adams in Our Time is on display from September 19, 2020 through January 3, 2021. For information, visit crystalbridges.org or call 479.418.5700. The exhibition was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Alejo Benedetti, associate curator of contemporary art, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2020 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|