Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age: Designer George A. Schastey

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recent acquisition and installation of the Worsham-Rockefeller Dressing Room, created by George A. Schastey for Arabella Worsham (later Huntington) in 1881–1882, has sparked new interest in the work of this little-known cabinetmaker and decorator. Schastey founded one of the foremost cabinetmaking and decorating firms of America’s Gilded Age, yet he has not received recognition equal to that of his peers and primary competitors, Herter Brothers and Pottier and Stymus. Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age: George A. Schastey, takes the first in-depth look at this inventive and artistic cabinetmaker.

Schastey immigrated to New York as a young boy in 1849, amidst an influx of Germans fleeing political and economic instability. He embarked on a career working with the city’s leading cabinetmaking and decorating houses, before opening his own firm in 1873. George A. Schastey & Co. worked largely on commission and came to rival the city’s other premiere firms. His firm’s distinctive Aesthetic style—strongly anchored in Renaissance ornament, punctuated by flourishes from the Islamic world and contemporary British reform design—is explored through objects that survive from Schastey’s most notable commissions.

The remarkable art case of this grand piano (Fig. 1) provided the key to unlocking the work of George Schastey. Through its abundant marquetry and carved ornament, the piano presents Schastey’s individual artistic sensibilities and direct parallels to other works attributed to his firm. He combined Renaissance motifs, such as the carved female busts on each leg that boldly emerge from the surface and are framed by cornucopias and lush flora, with bands of marquetry that echo stylized British reform design and Islamic motifs (Figs. 2a-b).

A log book entry for the piano’s serial number in the Steinway & Sons archives provided the critical documentation of the piano’s art case to Schastey, making it one of the few pieces of furniture definitively assigned to his shop. The entry confirms that Schastey’s firm received the piano in June of 1882 and it was “to be decorated & then sent to Newark N.J.” for the newly constructed residence of William Clark. A prosperous Scottish thread manufacturer, Clark commissioned Schastey & Co. to execute the complete interior decoration of his mansion, still standing today. These elaborate rooms merited inclusion in the sumptuous publication Artistic Houses (1883), although Schastey’s contributions went uncredited.

The late nineteenth century was a period of great innovation. In July of 1873, the same year he started his own firm, Schastey filed a patent for a new kind of chair reclining mechanism, which offered the sitter more stability and control by keeping the arms in an even plane. At the time, the United States Patent Office required that each submission be accompanied by a working scale model, and Schastey submitted a diminutively sized Renaissance Revival armchair (Fig. 3). Due to storage concerns, the Patent Office later removed the model requirement and sold many of the models. Remarkably, Schastey’s submission remains in near pristine condition with its original upholstery and paper tag.

As confirmed by a corresponding entry in a Tiffany & Co. log book, Schastey made the walnut case of this clock in 1881 (Fig. 4). The clock’s dial, engraved “Geo. A. Schastey & Co.”, along with its impressive scale suggests that it may have been made for Schastey’s offices or showroom. The varied treatment of the carved vegetation likely reflects the hands of two distinct carvers in Schastey’s workshop. The dramatic crenellated cornice and overall shape recall the innovative designs Schastey was concurrently executing for other clients such as Arabella Worsham and William Clark. Between 1879 and Schastey’s death in 1894, the firm created at least nine clocks in cooperation with Tiffany & Co., who fabricated clock works in addition to their better-known work in silver.

Around 1880 Schastey worked with designer W. August Fiedler to complete the interiors of the Samuel Nickerson house in Chicago. Fiedler, a German immigrant who trained in Europe, first settled amongst the leading New York City cabinetmaking and decorating houses before establishing his own Chicago-based design and architecture firm. By 1880, he was bankrupt and hired himself to Schastey, a colleague from his early years in New York, to finish the interior woodwork and furnishings of several rooms in the Nickerson house, including the satinwood drawing room. Fiedler briefly returned to New York in 1880, likely to work for Schastey as the firm finished his commissions.

A set of four satinwood armchairs designed en suite with the drawing room are among the few original furnishings to remain at the Nickerson mansion (Fig. 5). Typical of Schastey’s work, they reference a mix of historical styles. Several design flourishes, while not individually unique, taken in combination can be associated with Schastey’s emerging aesthetic: the square paw feet; the crowned sphynxes; and the handling of the carved oak leaf swags with trailing ribbons on the crest rail.

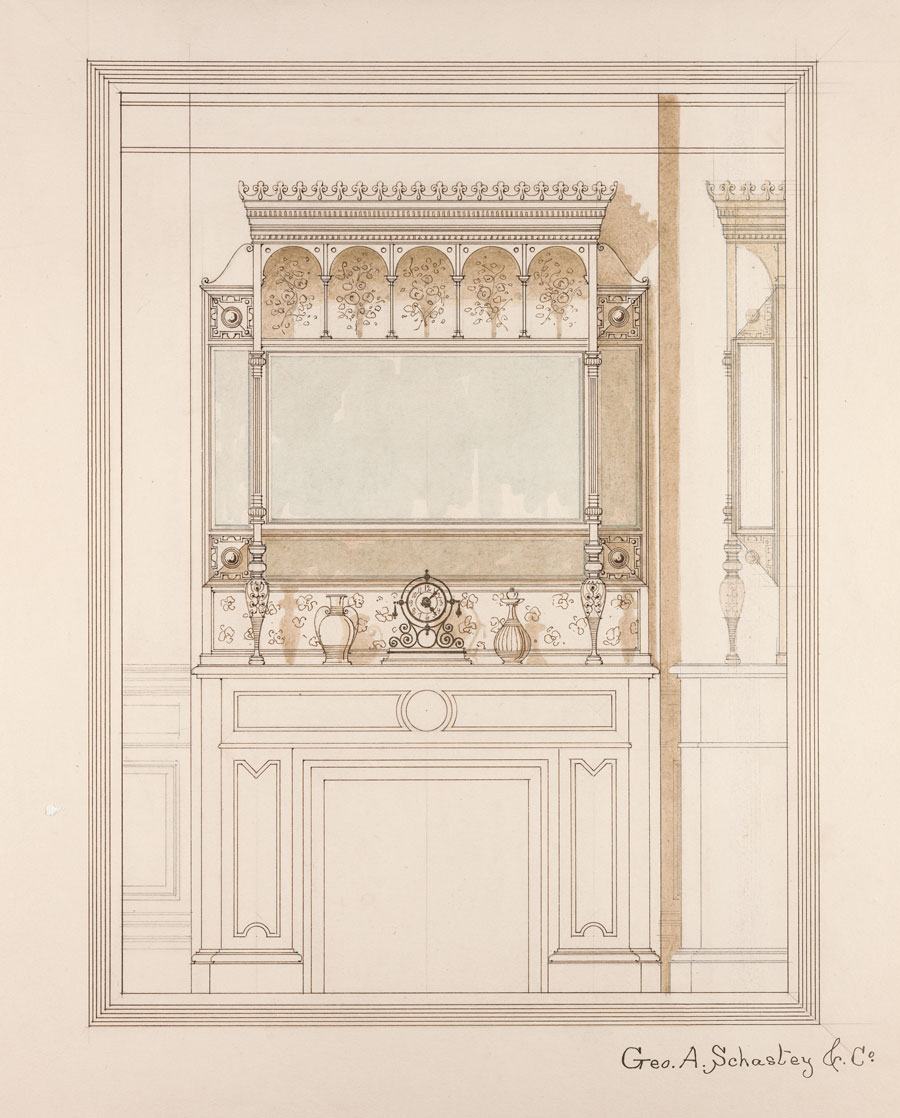

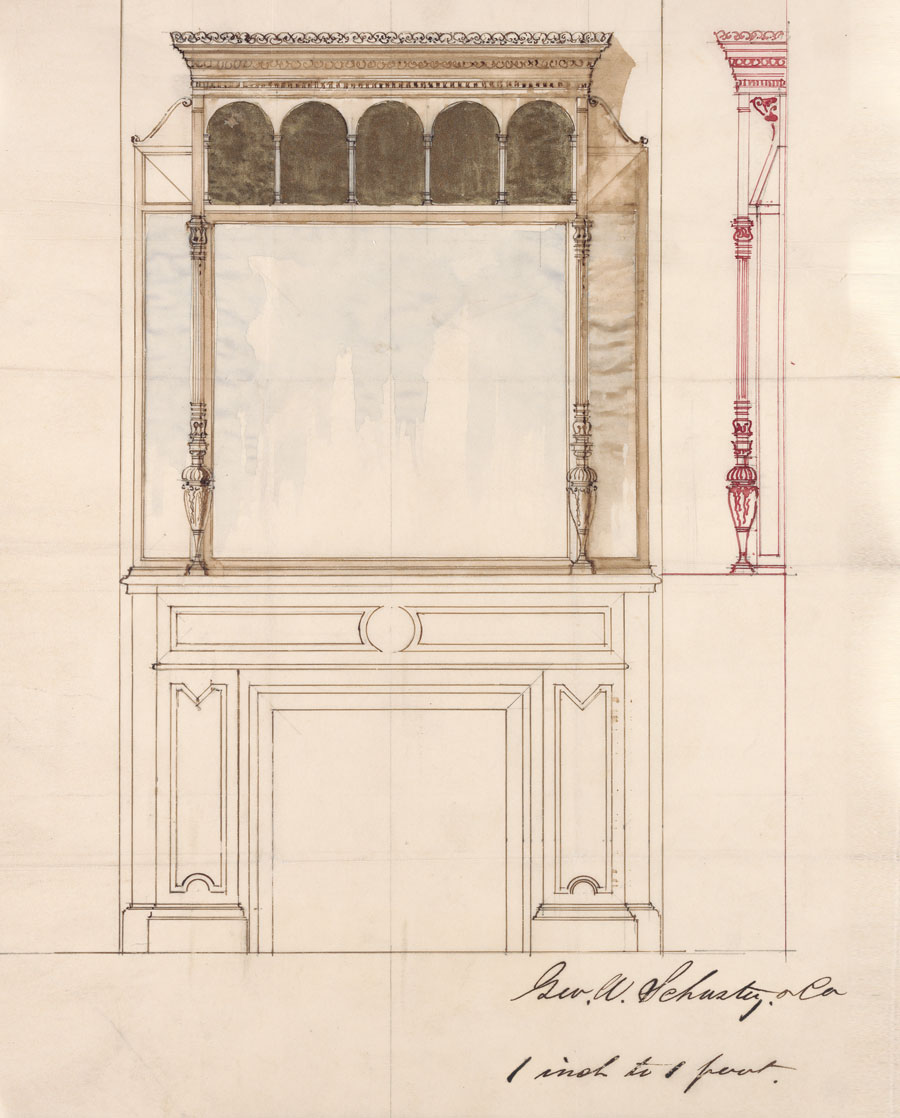

Schastey also proposed additional furnishings and interior decorations for Fiedler’s client, Edward C. Hegeler, a German-American zinc manufacturer and publisher residing in La Salle, Illinois. Fiedler had overseen the initial decoration of the Hegeler mansion between 1874 and 1876; however, by 1880, the family desired new draperies and additional furnishings. For this custom work, Schastey’s designers created sketches for approval by the client (Figs. 6a-b). A remarkable survival, these design drawings are two of only ten known to survive from Schastey’s enterprise, whose bespoke work depended heavily on these proposed studies. Each shows a frontal and profile view of the fireplace and proposes a design for a new overmantel on an existing fireplace. The secondary proposal, rendered on tissue paper, would have easily overlaid the primary drawing, which is more finely drawn.

- Fig. 7: Work table, George A. Schastey & Co. (1873–1897), New York City, 1881–1882. Purpleheart, satinwood, walnut, mahogany, poplar, brass, pewter or lead, mother-of-pearl, glass, unknown colored resin, original and reproduction textiles. H. 29-3/4, W. 40-3/8, D. 24-1/4 in. Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Museum of Art, Utica, N.Y. Museum purchase by exchange with gifts from Jane B. Sayre Bryant and David E. Bryant in memory of the Sayre Family, and from the H. Randolph Lever Bequest.

Arabella Worsham, the mistress and later wife of railroad magnate Collis P. Huntington, commissioned Schastey to decorate her newly renovated New York townhouse at 4 West 54th Street in 1881. Schastey designed each room in a distinctive, yet cohesive style, typical of the Aesthetic movement. A newly discovered photograph from 1883–1884 confirms that this sumptuous work table (Fig. 7), intended to hold sewing accoutrements, was among the original furnishings of Worsham’s bedroom, yet it was not designed en suite with the room’s other ebonized furniture. The table embodies Schastey’s most inspired period of production, with its artistic combination of international exoticism onto historical European forms. Its distinctive and complex inlaid ornament of metals and mother-of-pearl is now considered a hallmark of Schastey’s work.

Formerly attributed to Herter Brothers, this ebonized cabinet (Fig. 8) is now assigned to George A. Schastey & Co., and was part of the furnishings in Arabella Worsham’s drawing room at 4 West 54th Street, as confirmed by a recently discovered period photograph (Fig. 8a). Generous in scale, the cabinet’s form recalls Renaissance court cupboards and exhibits a variety of carved figures, flora, and garlands found in other Schastey-designed objects and interiors. Its most unusual features are the massive brasses in a loosely interpreted Moorish and Celtic style that feature brown and white agate “jewels,” similar to those that embellish the center table in the Moorish reception room, a feature perhaps unique in cabinetmaking of this era. The cabinet was slightly altered at an unknown date; however its survival opens the possibility that more pieces from Schastey’s best-documented commission survive.

Arabella Worsham’s Moorish reception room referenced the popular taste for the exotic, and drew heavily upon Islamic and Eastern architecture and design. After acquiring the fully-furnished house in 1884, John D. Rockefeller continued to patronize Schastey and likely purchased this center table (Fig. 9) from his firm to supplement the house’s existing furnishings. The key-hole, crenelated arches that support the table top strongly recall Islamic architecture and seamlessly integrate the piece within the striking interior Schastey created. The central plinth has flat, stylized carving of tendrils and abstract vegetal motifs, centered by green malachite bosses, a distinctive feature that Schastey used on other pieces in the Worsham-Rockefeller house.

In 1885, following the migration of his clients north to more fashionable midtown addresses, Schastey relocated his showroom from Union Square to West 53rd Street and Broadway. Shortly after its opening, the New York Times published a highly detailed description of Schastey’s new showroom. The account drew particular attention to this large cabinet (Fig. 10): “The most striking piece, however, is a large cabinet of amaranth inlaid with mother of pearl and silver . . . The centre [sic] panel is an elaborate design in the silver. Surrounding it the plainer surfaces are interspersed with stars of mother of pearl. Below a carved band is a fine inlay of brass, making another band, and below again come the richer forms in pearl and silver.” With its strong references to Islamic design and its glimmering surface ornament, this cabinet represents the luxury and worldliness that Gilded Age patrons sought to express in their furnishings.

This impressive cabinet (Fig. 11) originally stood at the base of the stairs in the entrance hall of the Worsham-Rockefeller house and conveys the grand scale of the now-demolished residence. It is one of several massive architectural elements preserved by the Rockefeller family before the house was demolished in 1938. The style of the cabinet relies on Baroque sensibilities with its massive, heavy scale and combination of figural carving, mythical sea-lions, and strapwork. Schastey infused these more traditional historical references with checkered carving and unusual molding profiles to create a more distinguished Aesthetic statement. Decorative and functional, the cabinet’s metal heating grates—produced locally in Brooklyn—feature oak leaves, a motif Schastey carried throughout the house’s interiors.

The three-part exhibition Artistic Furniture of the Gilded Age is on view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art through May 1, 2016, and includes over forty examples of furniture by Schastey and other noted design firms of the late nineteenth century. For information call 212.535.7710 or visit www.metmuseum.org.

-----

Moira Gallagher is a Research Assistant at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

This article was originally published in the 16th Anniversary (Spring 2016) issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available on www.afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and afamag are affiliated with InCollect.