Audubon’s Snuff Box

|

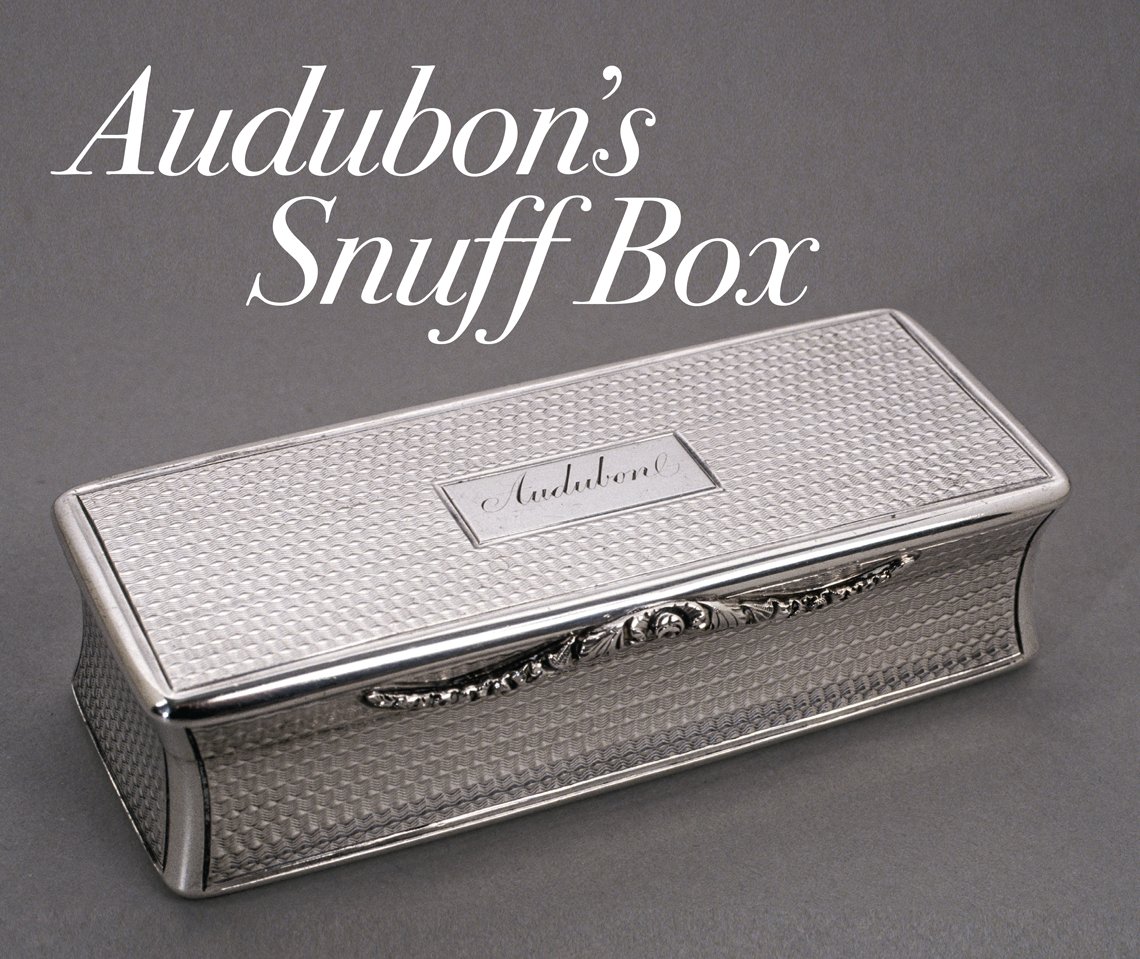

Fig. 2: Snuff Box, Nathaniel Mills (1766-1840), Nathaniel Mills & Sons, Birmingham, England. Date stamped 1831 and with maker’s hallmarks. Silver, 3⅜ x 1⅜ x ⅞ inches. Private collection. Photography by Will Brown. |

by Robert McCracken Peck

John James Audubon (1785–1851) casts a long shadow on the history of American natural history and art (Fig. 1). His publications on birds and mammals were among the largest and most beautiful ever made. His personality too was larger than life. One seldom discussed aspect of his colorful life is revealed by a small silver snuff box that has an English origin and an American provenance (Fig. 2). It was made by the Birmingham silversmith Nathaniel Mills (1766–1840) and given to the artist in 1831. Admiring the elegant simplicity of the box and the friendship it represented, Audubon kept it with him for the rest of his life.

| |

Fig. 1: John Smye (1795-1861), Portrait of J. J. Audubon, 1826. Oil on canvas, 35½ x 27½ inches. White House Collection/White House Historical Association. |

A Warm Reception in Charleston

In the fall of 1831, Audubon was visiting Charleston, South Carolina, on his second return to the United States since launching his landmark publication The Birds of America in Great Britain in 1827. He had spent the better part of the previous thirty years preparing for and producing the greatest bird book the world had ever seen. He had two important reasons for making this trip. The first was to gather source material with which to create additional plates for his “double elephant folio,” and text for its accompanying narrative, which he was publishing in a series of volumes under the title Ornithological Biography. The second reason for visiting the U.S. was to secure more American subscribers for The Birds of America, for which he was always in need of funds. He found Charleston a particularly fertile area for both activities.

On November 6, 1831, the forty-six-year-old naturalist wrote to his friend Dr. Richard Harlan in Philadelphia to tell him what a delightfully warm reception he had received in Charleston. “I have [been] struck by the generous hospitality of the Charlestonians,” he wrote, “and I am this day more amazed than ever. Everybody seems anxious to promote my wishes and comfort.” He was particularly happy to report that a Dr. Samuel Wilson, one of Harlan’s “old companions at college,”1 had just presented him with “a most excellent New Found Land Dog and a handsome silver snuff box.” To emphasize the warmth of the city’s residents and explain the usefulness of the second gift, he added that “the ladies of Charleston…contributed to our pleasure by giving us [an] abundance of good snuff.”2

The collective “we” refers to his traveling companion, the Swiss landscape painter George Lehman (ca. 1803–1870), who Audubon had hired to assist him with some of the backgrounds for his work. Samuel Wilson, the generous donor of these two gifts, was a doctor in Charleston who is frequently mentioned in Audubon’s Ornithological Biography as a source of many of his bird specimens and of first-hand information about the birds of the Charleston area.

The gifts were doubly noted by the grateful naturalist, for on the following day he gave a similar account of them to his wife, who was then living in Louisville, Kentucky. In a letter to Lucy, dated November 7, 1831, Audubon wrote: “Docr Saml Wilson, a friend of Docr Harlan, gave me an excellent & beautiful Newfound Land dog for which…I would not take 100 dollars, and a few days afterward he…presented me with a handsome Silver Snuff Box.” 3 Whether unconcerned by, or oblivious to, the unsettling impression his references to the attention of Charleston’s ladies might give his wife, Audubon boasted that: “The Ladies have brought me ½ a dozen bottles of snuff.”

| |

Fig. 3: John Woodhouse Audubon (1812-1862), Portrait of The Rev. John Bachman, ca. 1837. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 inches. Courtesy of The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina. |

There is no record of Lucy’s reaction to Audubon’s news, nor that of his friend and Charleston host, the Lutheran minister John Bachman (Fig. 3). We know that Reverend Bachman frowned on his friend’s fondness for tobacco, alcohol, and unattached women. He tried repeatedly to get Audubon to give up these vices. He succeeded, if only briefly, just a few months after Audubon announced his windfall of tobacco-oriented gifts from Charleston.4 “Thou wilt be surprised to read that I have abandoned Snuff for ever!” Audubon wrote his wife in January 1832.5 His resolution was short lived, for in June of the following year he was once again using it regularly.

Joseph Coolidge, the son of the man in charge of the revenue cutter on which Audubon traveled along the coast of Maine, wrote of the naturalist making a dramatic demonstration of his effort to abandon both snuff and alcohol. “Audubon was what you may term a free drinker, and, furthermore, he was a great snuff taker,” he recalled in 1896.6 “What liquors there were the old man [Audubon] collected, and as we were passing the Eastport Lighthouse he took a last drink and said to us, ‘Boys, no more drink for me.’ With that he threw the liquors into the waves. Then he fished out his snuffbox [probably a commercial tin or paper box], and after taking a pinch, exclaimed, ‘No more snuff,’ and flung the box and its contents after the liquors into the tide.”7

| |

Fig. 4: Trade Card, John Proctor, Manufacturer of British & Purveyor of Foreign Snuffs & Cigars, to his Majesty, ca. 1830. Engraving, 2.4 x 3.6 inches. Victoria and Albert Museum Department of Prints, Drawings & Paintings Collection; Gift of Mr. Aubrey J. Toppin, CVO (E.337-1967). |

Later in the trip, Audubon expressed his regret about having abandoned these vices. “I do not know what I would not give for a glass of good brandy,” he told Coolidge a few days after his flamboyant, vice-dumping gesture. Happily, for him, his young traveling companion was able to find a bottle of brandy that had been kept for medicinal purposes. Audubon was elated. “Now, how would you like a pinch of snuff?” followed-up Coolidge. “As mortals seldom obtain all they wish,” replied Audubon, “they should study to be contented with what they can get.” “But I can find you some snuff,” said Coolidge, who had brought a package on board as a gift for Audubon but had not given it after seeing the naturalist throw his own package overboard. “If you can [find it] you will be quite an angel,” replied Audubon. “When I brought the snuff to him,” recalled Coolidge, “he was as happy as a child on Christmas morning with a wealth of gifts in his lap.”8

| |

Fig. 5: Advertisement, Maccoboy Snuff, Manufactured by Edward Roome, Troy, N.Y., ca. 1844. Engraving, no dimensions. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. (Lot 10618-40). |

Audubon was not unique in his addiction to snuff, a ground and fermented form of tobacco that could also be scented. Columbus’ crew observed the inhaled product being used in the Caribbean in the fifteenth century and by the sixteenth century it had become a luxury trade commodity in Europe and China. Coveted for its “medicinal” qualities, it had taken hold in England by the next century and its influence continued to expand worldwide, including the Americas, where it had originated. (Figs. 4, 5). Snuff would be important to Audubon through most of his life. In a letter of 1838, he described himself as a “Hypocondriacal of 53 Years of Age” who was “thank God yet able to put his fore finger and thumb up to his nose holding withal a pinch of the ‘American Gentleman’—(Snuff! Snuff!).”9

When Audubon launched his second ambitious book project, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, with Bachman as co-author, in 1839, Bachman optimistically predicted that the project would not only prove a “profitable speculation” for both of them, but that it might keep Audubon “from snuff and grog” in his final years.10 Unfortunately, his old friend’s habits were too firmly ingrained to permit such a healthful change. “I do not believe that I will ever be a teetotaler,” he wrote Bachman in 1843. “I drink good wine and take a good deal of snuff, and if I can continue to do so for the next 20 years, I will not care a jot about the science of teatotallism.”11 When Audubon died in 1851, a dozen years short of his goal, the Nathanial Mills snuff box that he had received as a gift twenty years before, was still by his side.

Audubon’s Snuff Boxes

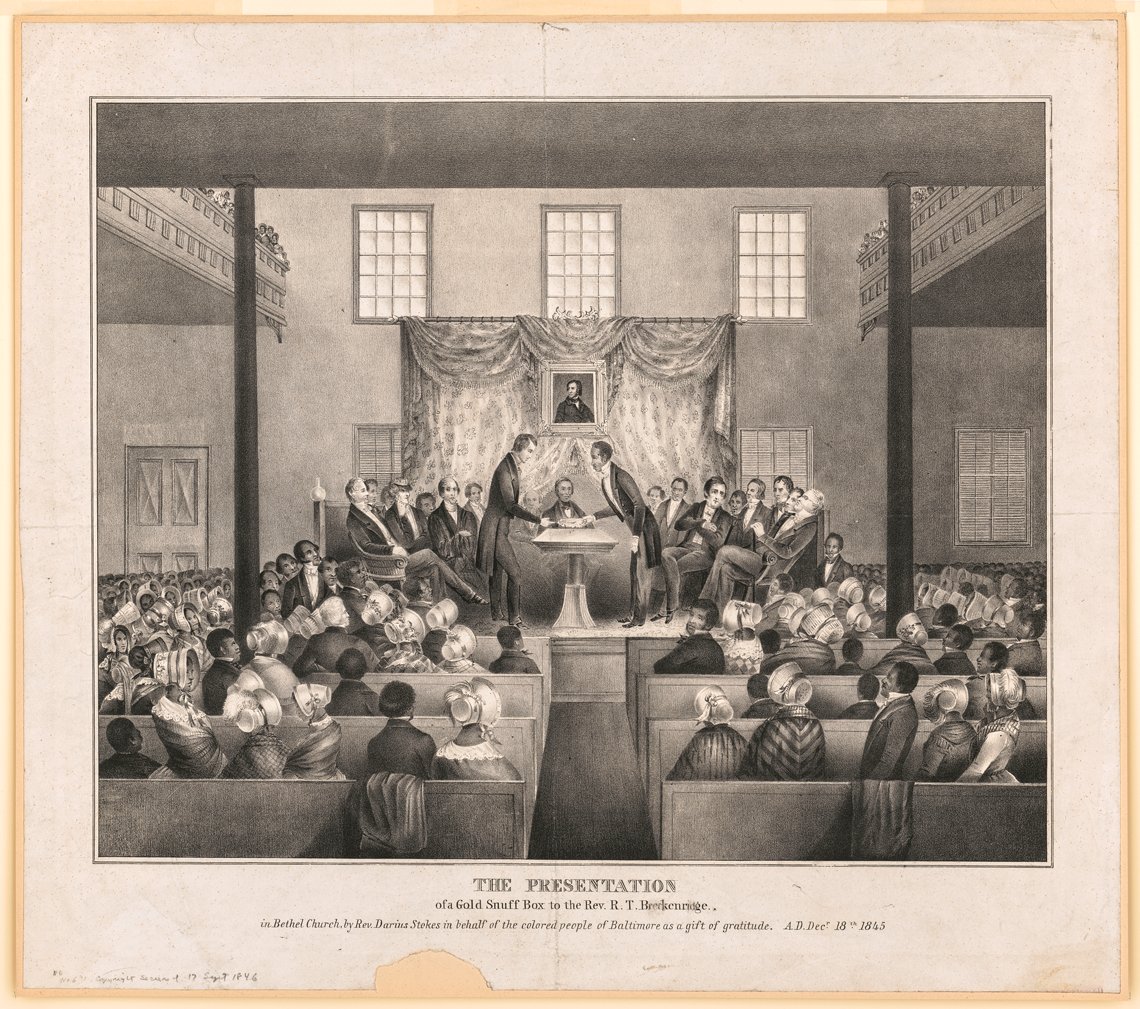

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, snuff boxes were frequently exchanged between friends, or presented as tokens of high esteem (Fig. 6). Audubon was given at least four during his lifetime. The first he recorded was a silver box with the engraving of a pheasant on its lid. Made in Manchester, England, in 1826, it was given to Audubon by John Rutter Chorley, a British railway official Audubon had met in Liverpool shortly after his arrival there.12 Because the engraved bird was derived from the illustration of another artist, Audubon was probably less than enthusiastic about owning or using this box, despite his respect for its donor. In 1828, he reported putting it away forever when he first tried to give up the use of snuff. “Now, my Lucy,” he wrote his wife on January 1, “when I wished thee a happy New Year this morning I emptied my snuff box, dump[ed] the box in my trunk, and will take NO MORE. The habit within a few weeks has grown upon me, so farewell to it; it is a useless and not very clean habit, besides being an expensive one.”13

Like many New Years’ resolutions, Audubon’s decision to give up snuff was too hard for him to maintain, for, as he noted in his journal, “I missed my snuff . . . the strength of habit thus acting without thought.”14 Certainly by 1831 he was again using snuff regularly and was more than happy to receive copious quantities of it, along with the new snuff box presented to him by his friend in Charleston.

|

Fig. 6: The Presentation, ca. 1845. Text below the image states “THE PRESENATION/of a Gold Snuff Box to the Rev. K. T. Breckenridge/in Bethel Church. By Rev. Darius Stokes in behalf of the colored people of Baltimore as a gift of gratitude. A.D. Dec. 18th 1845.” Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. (LC-DIG-pga-07916). |

He was given his third English snuff box by Thomas Henry Liddell, the first Earl of Ravensworth, in 1836. Unfortunately, although Audubon refers to this gift in at least two letters, we know nothing more about it.15

The most elaborate, valuable, and symbolically most significant snuff box owned by Audubon was a diamond-encrusted presentation piece from Nicholas I, the Emperor of Russia. It was transmitted to him by the tsar’s emissary, Alexis Krudener, in the summer of 1841.16 Although Audubon undoubtedly enjoyed the social cache associated with this gift, he appreciated its monetary value more, for he wrote his friend Benjamin Phillips to ask how much the snuff box might be worth if he were to sell it. Phillips replied, “with reference to the snuff box, … I now find that from £45 to £50 is the amount which may probably be obtained for it.17 Supposing the diamonds to be taken out and paste substituted for them, the cost of the substitutes would not be above £4 or £5. The cost of mounting the diamonds, supposing them to be removed, would depend upon the manner in which it is done. I shall hold the box for your orders.”18 If Audubon did attempt to sell the box, he was unsuccessful, or perhaps he had a change of heart and decided to keep it as a prestigious showpiece. In any case, the box was still in the family’s possession in the 1860s, when Lucy asked her brother, William, how to go about selling it.19

The snuff box under discussion here, his second, is an elegantly simple silver box of rectangular shape (fig. 2). It bears an 1831 date stamp and the maker’s mark of the Birmingham silversmith Nathaniel Mills on both the inside of the lid and the inside of the bottom of the box. It has incurved (concave) sides, engine turned surface decoration, and an applied garland on the front. The name “Audubon” is engraved in cursive script on a rectangular reserve on the top of the box.

Nathaniel Mills was in partnership with his sons, William and Thomas, in the firm Nathanial Mills & Sons, in Birmingham in the 1830s. They excelled in making small silver items such as vinaigrettes, snuff boxes, and card cases for both domestic consumption and export. Samuel Wilson probably bought the snuff box from a silversmith or import-export merchant in Charleston and presented it to Audubon within a few months of its manufacture. Because of its plain, unadorned appearance and practical design, it was the snuff box the artist appears to have adopted for daily use, and it is the only one of Audubon’s snuff boxes that has survived to the present day (or is, at least, the only one whose present whereabouts is known). Its ownership in subsequent years tells us something about the sad state of Lucy Audubon’s financial situation in the years following the loss of her husband.

A Distressed Widow Makes a Gift

In the spring of 1862, just over a decade after John’s death, Lucy, then seventy-five, was finding it increasingly difficult to handle the deteriorating condition of her family affairs. Predeceased by three of her four children (her daughters Lucy and Rose in 1814 and 1819, respectively, and her oldest son, Victor Gifford, in 1860), Lucy had come to rely on her second son, John Woodhouse Audubon, to handle the financial affairs of the family. When he died in 1862 at the age of forty-nine, “without leaving a dollar in the bank,” Lucy turned to her lawyer and long-time family friend, George Burgess, for counsel.20 Burgess helped Lucy to rent out, and later sell, the family properties in New York, and did his best to guide her through the “tangled and confused state” of her family’s finances.21 He also quietly solicited Audubon’s friends to help underwrite her living expenses.

In a letter to her husband’s former patron and traveling companion, Edward Harris, in New Jersey, Burgess discretely explained that Audubon’s distressed widow and granddaughters, who lived with her, were “somewhat cramped for ready cash for daily current living expenses and have to call on their friends” for help.22 Lucy was more direct in describing her situation when she wrote Harris a few days later to thank him for his “loan.” “I really am unhappy and very destitute” she confessed.23

Desperate for money, and too proud to ask for charity, she turned to John’s original watercolors for The Birds of America as a source of cash. “I must sell [them] for what I can get,” she wrote Harris, “and the copper plates by weight as old copper! Thus, as my poor ruined Brother writes, ‘the work of years of toil, and such as will never again be seen are handed about like an old newspaper, and the widow of such a man [is] not sure of a living’.”24 With Burgess’s help, the watercolors were eventually sold to the New York Historical Society for $4000 in 1863.25

| |

Fig. 7: Amelia Jane Havell, Portrait of Robert Havell, Jr., 1845. Graphite and watercolor on paper, 5 ¾ x 4⅛ inches. Drawn by Havell’s eldest daughter at Sing Sing (Ossining), New York. Current location unknown. |

Audubon’s treasured snuff box was among the few things of value that remained with Lucy. It may have come directly to her at the time of her husband’s death or been inherited and owned by John Woodhouse Audubon in the 1850s. In any case, by 1862 it was in Lucy’s possession. Since she could not afford to pay her lawyer cash for his services, she sometimes reimbursed him for his time and professional services with items of value from her household.26 As close friends of Lucy’s, George Burgess and his wife, Valeria, would have treasured Audubon’s snuff box, not just for its monetary value, but as a keepsake of their long association with the artist and his widow. Thomas Burgess, the lawyer’s son, subsequently inherited the box from his father. It then passed to his widow. She loaned it to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia for inclusion in its landmark 1938 national exhibition on Audubon and his work.27 Mrs. Burgess retained ownership of the snuff box into the 1950s.28 It was acquired by the well-known silver collector James H. Halpin sometime after that and was purchased by the current owner at the Halpin sale at Christies in New York, on January 22, 1993.29

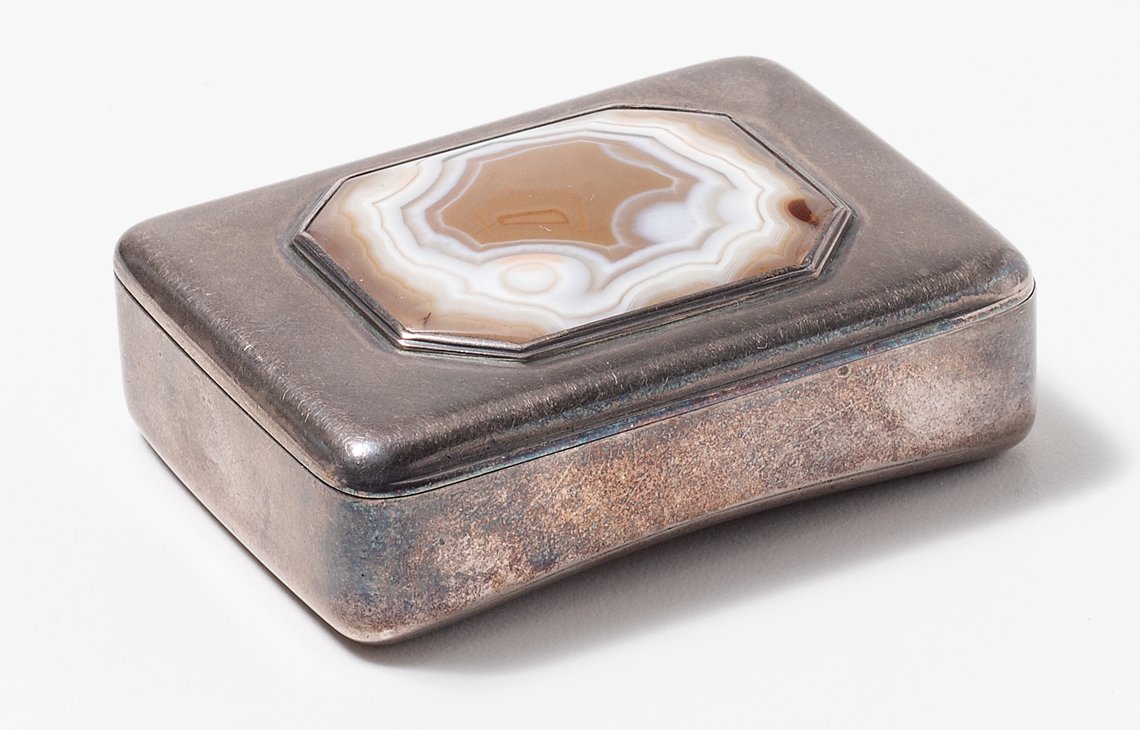

The only other snuff box associated with John James Audubon is one that he presented to his friend, the engraver Robert Havell, Jr., in 1835 (Fig. 7). The silver box, now in the Audubon Museum in Henderson, Kentucky, is rectangular and hinged with a brown-and-cream-colored agate stone mounted on the lid in a window setting. The back is curved and engraved: “Robert Havell Esq./from/John J. Audubon/1835” (Figs. 8, 8a).30 Five British silver hallmarks inside the box and three hallmarks on the inside of the lid indicate that the makers were Thomas Phipps & Edward Robinson, well-known London silversmiths, and that the box was made in 1806–1807, long before Audubon acquired it. Like Audubon’s own snuff box, the Phipps & Robinson Havell box has a gold-plated interior.31 The date of the inscription suggests that Audubon gave this to Havell as he approached completion of the third volume of The Birds of America.

|

Fig. 8: Snuff Box, Thomas Phipps & Edward Robinson, London, 1806-1807. Silver and agate with gold-plated interior. H. 1⅞, W. 2½, D. ⅞ inches. Courtesy of John James Audubon State Park, Henderson, Kentucky. Images courtesy of Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture (JJA.2014.3.1). |

| |

Fig. 8a: Detail of Snuff Box underside. Engraved: “Robert Havell Esq./from/John J. Audubon/1835.” |

The professional relationship that existed between Audubon and Havell is evident in the great book they produced together, but it was their shared love of snuff, and Audubon’s gift of this box, that gives us an insight into the close personal friendship that must have existed between them.

While Audubon’s artistic ability and life-long obsession with birds sets him apart from most of his contemporaries, his fondness for snuff was not unusual in the nineteenth century. His various snuff boxes, both given and received, provide tangible evidence of his addiction to nicotine, and give us a glimpse into one small part of his rich, productive, and controversial life.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank David Barquist, the H. Richard Dietrich Jr. Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, for providing a formal description of the Audubon snuff box, and Alice Irwin for helping me contact various members of the Audubon Family in hope of locating other snuff boxes owned by the artist (without success). I also wish to thank Jennifer Spence, former State Curator, Kentucky Department of Parks, Tourism, Arts, & Heritage, for her help with materials at the Audubon Museum in Henderson, Kentucky. The Audubon scholars who assisted me with my research were the late Alice Ford, Roberta Olson, Ron Tyler, William Souder, Richard Rhodes, Peter Logan, Martin Sidor, Christine Jackson, and Christoph Irmscher. To all of them I extend my heartfelt thanks.

Exhibition History John James Audubon—A National Exhibition, Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, April–June, 1938 (item # 90, exhibition catalog, p. 29). Audubon in the West: The Last Expedition, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming, May 2000– June 2001. This exhibition travelled to: The Buffalo Bill Historical Center; The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia; The Houston Museum of Natural History; and the Autry Museum of Western Heritage, Los Angeles. Audubon’s Aviary: The Complete Flock, The New York Historical Society, New York City, March–May 2014. John James Audubon: Obsession Untamed, Rosecliff, The Preservation Society of Newport County, Newport, Rhode Island, March 30–September 30, 2019. J. J. Audubon, Sharon Historical Society, Sharon, Connecticut, October 1–December 31, 2019. | |||

1. Harlan and Wilson were both members of the University of Pennsylvania medical class of 1816.

2. Letter from J. J. Audubon to Richard Harlan, November 6, 1831, Collection of College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

3. Letter from J. J. Audubon to Lucy Audubon, November 7, 1831, Howard Corning, ed., Letters of J. J. Audubon 1826-1840 (Boston: Club of Odd Volumes, 1930), Vol. 1, 147–149.

4. For examples of Bachman’s efforts to have Audubon give up “grog and snuff,” see his letters of January 26, 1840, and November 29, 1843, both at the Charleston Museum.

5. Letter from J. J. Audubon to Lucy Audubon, January 16, 1832, Letters of J. J. Audubon, 176.

6. “A Californian’s Recollection of Naturalist Audubon,” The San Francisco Call, Sept. 6, 1896, quoted in Peter B. Logan, Audubon in Labrador, (San Francisco: Ashbryn Press, 2016), Appendix I, 507.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid., 509.

9. Letter from J. J. Audubon to John Bachman, April 14, 1838, in Audubon Writings and Drawings, Christopher Irmscher, ed. (New York: The Library of America, 1999), Vol. 2, 848. While in America, Audubon seems to have preferred American snuff, but when living in England he used snuff manufactured there and in Europe. Peter Logan has determined that Audubon’s favorite snuff while in London was “Hardham’s No. 37,” a mixture of Dutch and rappee snuff, developed in the 18th century by John Harham of Fleet Street and used by Sir Joshua Reynolds and other fashionable figures of the era. Personal communication with Peter Logan, May 31, 2021.

10. Letter from John Bachman to J. J. Audubon, July 5, 1839, Harris Papers, Alabama Department of Archives and History.

11. Letter from J. J. Audubon to John Bachman, December 10, 1843, Houghton Library, Harvard University, collection # bms AM 1482 (161).

12. Alice Ford, John James Audubon: A Biography (New York: Abbeville Press, 1988), 193. John Rutter Chorley (1807?–1867), with whom Audubon first became acquainted in Liverpool, was the secretary to the Grand Junction Railway between Liverpool and Birmingham and a person to whom Audubon became “warmly attached.” during his time in England. Christine E. Jackson, John James Laforest Audubon: An English Perspective (U.K: privately published, 2013), 41.

13. See Richard Rhodes, John James Audubon: The Making of an American. (New York: Knopf, 2004), 303.

14. Audubon journal, Jan. 1, 1828, quoted in Francis Hobart Herrick, Audubon the Naturalist (New York: D. Appleton-Century, 1938).

Audubon’s Silver Snuff Box — Provenance: John James Audubon—gift from Dr. Samuel Wilson, Charleston S.C., November, 1831; John Woodhouse Audubon (?)—gift or bequest of John James Audubon; Lucy Audubon—bequest of John James Audubon in 1851, or of John Woodhouse Audubon in 1862; George Burgess (Audubon’s attorney)—gift of Lucy Audubon; then by descent to Thomas Burgess (son) and Mrs. Thomas Burgess; James H. Halpin—purchased from Mrs. Thomas Burgess (date unknown, circa 1950); Present owner—purchased at Christies American Silver Sale, January 22, 1993, Lot # 50. | |||

15. See letter from J. J. Audubon to John Bachman, May 29, 1836, in Letters of John James Audubon, 119–120. See also letter from J. J. Audubon to Lucy Audubon, June 8, 1836, Audubon Museum, Henderson, Kentucky.

16. Ford, A Biography, 386.

17. The Wiskonsan [sic] Enquirer (Madison, Wisconsin), July 16, 1842, claimed the snuff box was worth $2000: “Mr. Audubon, the ornithologist, has received a gold snuff box, set in diamonds, from the Emperor of Russia. The box is of splendid workmanship and is supposed to have cost not less than $2000.” I am indebted to Andrée M. Miller, Curator of the John James Audubon Center at Mill Grove, Montgomery County Division of Parks, Trails, and Historic Sites, for this reference.

18. Letter from Dr. Benjamin Phillips to J. J. Audubon, in Ford, A Biography, 386.

19. Alice Ford, personal communication, October 16, 1993. In her 1988 biography of Audubon, Ms. Ford incorrectly states that Audubon sold the box, but her subsequent research revealed that this was not the case. My attempts to trace the snuff boxes mentioned in Audubon’s correspondence, have, so far, been without success.

20. Letter from George Burgess to Edward Harris, April 26, 1862, Harris Collection, State Archives of Alabama.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Letter from Lucy Audubon to Edward Harris, April 28, 1862, Harris collection, State Archives of Alabama.

24. Letter from Lucy Audubon to Edward Harris, October 16, 1862, Harris collection, State Archives of Alabama.

25. Richard Rhodes, John James Audubon: The Making of an American (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004), 436. Rhodes claims the cost was $2000, but Roberta Olson, the curator in charge of this collection, says the actual cost was $4000. See Roberta J. M. Olson, Audubon’s Aviary: The Original Watercolors for “The Birds of America (New York: Rizzoli, 2012), 35.

26. Personal correspondence from Alice Ford, October 16, 1993. “Burgess and his wife Valeria kept in close touch with her [Lucy Audubon]. What she could not repay in cash she tried to repay in gifts. I have no doubt that it was Lucy who gave him the snuff box.” Also “I do not doubt that the [snuff] box came from Lucy for favors done.” Personal correspondence October 26, 1993. According to Ms. Ford, Lucy also “gave the Burgesses a number of folio proof sheets ‘for the children to color’ or play with.”

27. John J. Audubon: A National Exhibition catalogue, item 90, Philadelphia, 1938, 29. Basing the information on Burgess family lore, the catalogue incorrectly states that the snuff box had been a gift to Audubon by Louis Philippe (1773–1850), King of the French from 1830 to 1848, the last King and penultimate monarch of France.

28. Alice Ford, personal correspondence, October 16, 1993 “They [the Burgesses] had a New York City house where, no doubt, [the 1831 Nathaniel Mills snuff] box spent some years. I have a dim recollection that Mrs. Thomas Burgess hoped to sell it in the 1950s when I met her, briefly, in the city.”

29. Important American Silver: The Collection of James H. Halpin, Christies, New York, Friday, January 22, 1993 (Sale HALPIN-7624).

30. Although the generational title “Junior” is not indicated in the engraving of the snuff box’s recipient, he was certainly the one for whom Audubon’s gift was intended, for Robert Havell, Sr. had died in 1832.

31. I am indebted to Jennifer Spence, the former State Curator, Kentucky Department of Parks Tourism, Arts, & Heritage, for this information, and to Heidi Taylor-Caudill, the current curator at the Audubon Museum in Henderson, for making images of the Havell snuff box available.

Curt DiCamillo is Curator of Special Collections, American Ancestors / New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS).

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2021 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|