Audubon Then & Now at the Biggs Museum of American Art

J

.jpg) | |

Fig. 1: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Wild Turkey (Meleagris Gallopavo), 1827–1839. Hand-colored engraving, 38 x 25½ inches. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Library and Garden (1959.0162.001). |

ohn James Audubon (1785–1851), arguably one of the most important artists of nineteenth-century America, remains a major influence in the visual arts today (Fig. 1). But while his contribution to early scientific research is still celebrated, little has been said about his impact on later artists. Audubon, Then and Now, at the Biggs Museum of American Art, seeks to redress that fact and to uncover his influence on contemporary artists. The exhibition pairs Audubon prints, from the collections of the Biggs Museum, Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library, and the Huntsville Museum of Art, with contemporary works by American and British artists influenced by the tradition of naturalist artists.

Born in Haiti and raised in France, Audubon was sent to live on the family-owned estate near Philadelphia at the age of eighteen, partly to escape conscription into the Emperor Napoleon’s army. As a young man he pursued several careers, but met with success only in recording the appearance, habitats, and behavior of first birds and then mammals of North America. Audubon’s legacy rests on his three major publications: The Birds of America (1827–1838); Ornithological Biography, or, An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America (1831–1839), co-written with William MacGillivray; and Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America (1845–1848), his study of mammals conducted with his son John Woodhouse Audubon.

As a result of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, which involved the acquisition of Louisiana territory by the United States from France, and the Lewis and Clark Expedition, commissioned shortly after by President Jefferson to map the newly acquired land and find a route across the western half of the country, millions of Americans moved into these new territories in the first half of the 1800s. Audubon pursued a similar mobility, exploring from Eastern Canada to Florida and as far west as the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers.

Audubon’s images of birds, mammals, and their habitats were some of the first commercially available views of North America and helped viewers to understand the topographical diversity of the growing country. The artist revered nature and its animals and sought to understand their behaviors and environments with a romantic, even idealized zeal. In his Ornithological Biography, Audubon recorded details of migration patterns, mating rituals, gender differences, and much more.

|

Fig. 2: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Roseate Spoonbill (Platalea Ajaja), 1836–1839. Hand-colored engraving, 25½ x 38½ inches. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Library and Garden (1959.0162.176). |

|

Fig. 3: Deidre Murphy (b. 1967) Red Bud, 2015. Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 inches. Courtesy of the Gross McCleaf Gallery. |

The commercial success of Birds of America was rooted in the pseudoscientific detail of Audubon’s images; he labored upon his depictions of color and texture (Fig. 2), as much as on his delineation of feathers, patterns, and shapes. Such vivid imagery can be seen in the work of contemporary artists today, such as Deidre Murphy’s Red Bud (Fig. 3), which glorifies the intensity of colors that made Audubon’s bird images so impactful.

Audubon’s passion to record animal species brought tremendous attention and greatly expanded understanding of the animal world. This attention, however, was not always beneficial and highlights the duality of preservation and hunting that resulted from his work. In order for Audubon to capture such vibrant hues in his images of birds, for instance, he had to replace the carcasses as their colors faded, recreating the scenes he was drawing by mounting and posing the birds on wooden boards with wire, hunting the specimens as needed. Audubon’s images actually bolstered a dramatic increase in sport hunting, in the fashionable use of feathers and furs in clothing and crafts, and in recreational travel. The subjects of many of Audubon’s images are now endangered, or even extinct.

|  | |

| Left: Fig. 4: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Carolina Parrot (Psittacus Carolinensis), 1831–1839. Hand-colored engraving, 38 x 25½ inches.Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Library and Garden (1959.0162.017). Right: Fig. 5: Kate MacDowell (b. 1972), Clay Pigeons, 2010. Terracotta, photograph. Courtesy of the artist and Mindy Solomon Gallery. | ||

|

Fig. 6: John James Audubon (1785–1851) Canvas backed duck (Fuligula Vallisneria) with view of Baltimore, 1836–1839. Hand-colored engraving, 24⅜ x 36⅝ inches. Courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Library and Garden (1959.0162.161). |

|  | |

| Left: Fig. 7: Julie Blackmon (b. 1966), Waiting Room, 2016. Archival pigment print, 35¾ x 35¾ inches. Courtesy of the Robert Mann Gallery, copyright Julie Blackmon. Right: Fig. 8: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Canis (Vulpes) Virginianus, Grey Fox, 1843. Lithograph, 21⅞ x 27⅞ inches. Biggs Museum of American Art, Del. | ||

Audubon even shared insights into effective hunting patterns, informing enthusiasts which animals could be domesticated, and even which types of animals made the best meals. When describing the Carolina Parakeet (Fig. 4), for instance, he noted that it was easily dispatched and a nuisance of the American farmer. He once noted that Passenger Pigeons could number in the hundreds of thousands at one viewing and were an excellent food source and easily hunted. While the wildlife numbers of early America no doubt seemed limitless to many of the naturalist societies, and Audubon himself boasted of his kills, the artist also recognized that westward expansion was decimating some animal populations and destroying their habitats. Thus, his drawings not only recorded species for research but, in many instances, recorded them for posterity. It was this observation, coupled with the tragic knowledge of this bird’s eventual fate, that influenced Kate MacDowell’s performance and sculptural installation entitled Clay Pigeons (Fig. 5). Once sculpted, her Passenger Pigeons were destroyed with a shotgun, to warn against the large-scale damage that can be inflicted through irresponsible hunting practices. The pieces, often riddled with lead shot, were reassembled into museum installations. Like the Carolina Parakeet, the Passenger Pigeon became extinct through overhunting.

Audubon’s background imagery is often as important as his depictions of birds and mammals, and help distinguish the artist from his peers. Audubon’s subjects are shown in their natural habitats, replete with details such as food sources, camouflage, nesting habits, and relationship to encroachment. Not consciously a regionalist artist, Audubon’s work also provided views of an expanding North America for a market hungry for information about this continent, recording impressions of little-known landscapes and cities (Fig. 6). Audubon was assisted by several painters who worked on many of his background details. Contemporary artist Julie Blackmon offers a vision of western expansion in images very different from Audubon’s (Fig. 7), but both artists use animal subjects to convey human experiences. Many of Audubon’s images place his presumably wild animal subjects in direct relationships to human habitations, such as cabins, plantations, cities, cultivated fields, allowing his viewers to see their own material progress through the perspective of the animals. Similarly, Blackmon signals how modern humans can track phases of their lives and define status through their relationships with animals.

|

Fig. 9: Ann Chahbandour, Beyond Audubon, Woodpeckers, 2016. Gouache on paper, 24 x 30 inches. Courtesy of the artist. |

|  | |

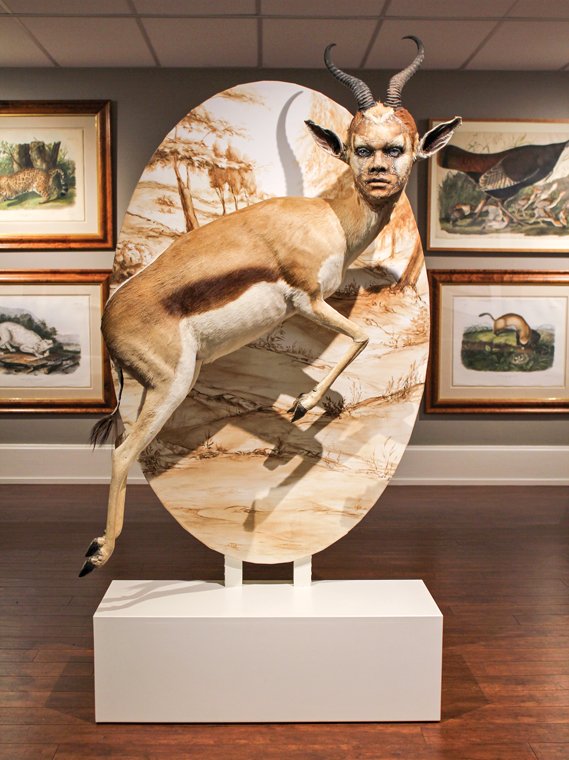

| Left: Fig. 10: John James Audubon (1785–1851), Common American skunk (Mephitis americana), 1844. Hand colored lithograph, 27⅞ x 21⅞ inches. Courtesy of the Huntsville Museum of Art, Collection of Mr. & Mrs. William H. Told Jr. Right: Fig. 11: Kate Clark (b. 1972), Charmed, 2015. Taxidermy, painted canvas, 60 x 33½ inches. Courtesy of the artist. | ||

Audubon’s work offers a variety of narratives for his animal subjects, as in the example of a gray fox chasing a feather (Fig. 8). The viewer is left to ponder if it is a leftover from a recent meal, or if the image is meant as a cautionary tale of what happens to farm livestock if not secured. The artist has composed a sophisticated narrative with a protagonist, an antagonist, and a range of possible storylines. The dramas that Audubon envisioned around his subjects created an appealing visual variety in the hundreds of prints created for Birds of America and Viviparous Quadrupeds, and are directly referenced in Ann Chahbandour’s recent series of paintings and sculptures (Fig. 9). Her woodpeckers are cast in stage productions, acting out discussions while framed by theater curtains. In doing so, Chahbandour playfully reshapes the image of Audubon as more of a showman than a naturalist.

Audubon positioned his supporters to be the audience of the animal world and to identify with the characters of his narratives. He often personified his animal subjects with naïve, loving and even vengeful personalities (Fig. 10), presumably to make them more familiar to his viewers. While Audubon never strayed too far into fantasy in his own work, other visual artists have grappled with the intersecting concepts of the natural and civilized worlds to produce hybridized subjects. Kate Clark sculpts taxidermy (Fig.11) into characters reminiscent of mythology. Her sculptural installations honor the long tradition of taxidermy while alluding to psychological states of being that are universally human.

|

Audubon, The and Now was on view at the Biggs Museum of American Art, Dover, Delaware, from August 3rd through November 25th, 2018. For more information, visit www.biggsmuseum.org.

|

Ryan Grover is the Sewel C. Biggs Curator of American Art at the Biggs Museum of American Art.