Augustus Fuller (1812–1873) — Triumph over Disability: A Deaf Folk Portrait Painter in Nineteenth-Century America

| |

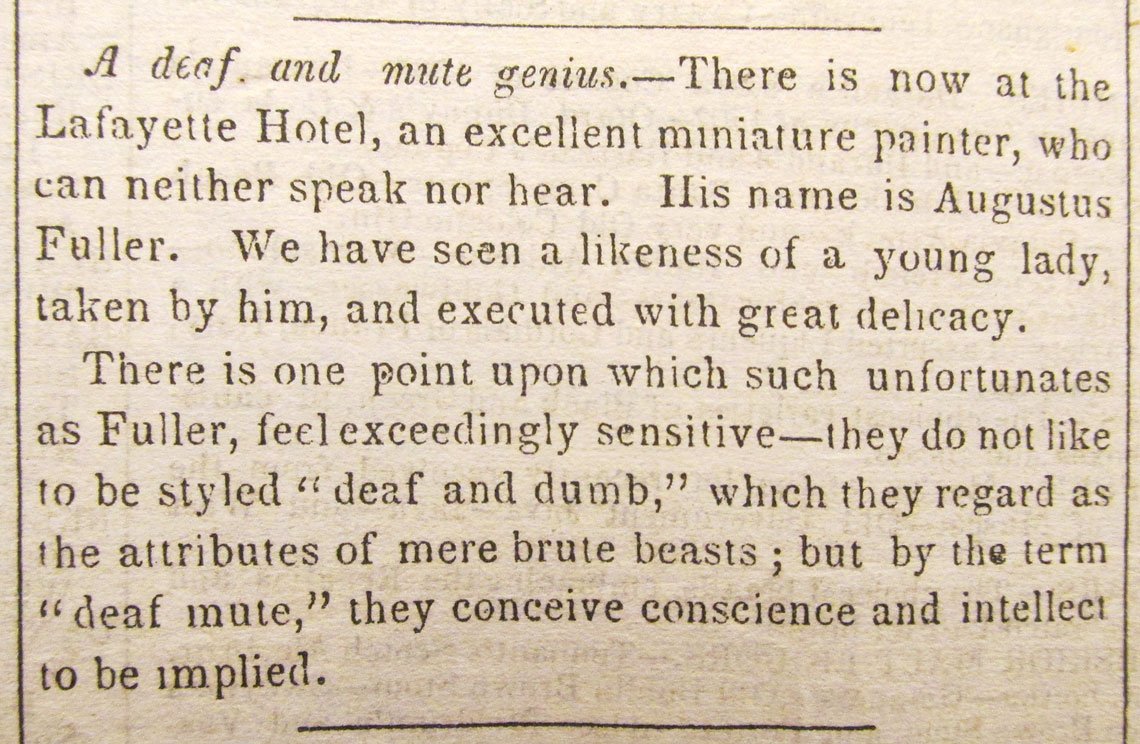

| Fig. 1:Greenfield Gazette and Mercury, Greenfield, Mass., December 1830. |

In 1817, Reverend Thomas Gallaudet, an educator interested in the deaf, and Laurent Clerc, an expert in sign language, established the Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons in Hartford, Connecticut.1 One of the first schools for the deaf in America, its students were taught the new French system of sign language and how to read and write.1a At a time when the deaf were objects of fear and prejudice, the Asylum represented a remarkable educational breakthrough. Among the people heartened by this new school was Aaron Fuller (1786–1859), who had two congenitally deaf sons, Aaron Jr. and Augustus.

The late 1810s were a time of great transition for the Fuller family.2 Aaron Fuller’s first wife, the mother of five children, including the two deaf boys, died in 1818. The family then moved to a prosperous farm in Deerfield, Massachusetts. In 1820, Fuller married Fanny Negus of Petersham, Massachusetts. Fanny’s father was an ornamental painter, her two brothers were artists, and her sister Caroline, who grew up in the Fuller home, would become a noted miniature painter.

|  | |

| Fig. 2: Augustus Fuller (1812–1873), Child on Red Sofa, North Adams, Mass., 1840. Watercolor on ivory, 2¼ x 1¾ inches. Inscribed verso “Augustus Fuller, pinxt/North Adams Dec 25/1840.” Collection of Pat and Fred Robichaud. Photograph by the authors. | Fig. 3: Augustus Fuller (1812–1873), Young Child Holding a Bell, 1853. Watercolor on ivory, 3 x 2¾ inches. Inscribed on paper attached to the back, “Augustus Fuller, pinxt/Dec. 14, 1853/Deaf and Dumb.” Photograph courtesy of Sotheby’s. The inclusion of a bell may signify that the child was deaf. |

---Elizabeth-Stone-Denny-Miniature.jpg) | ---Edwards--Denny-Miniature.jpg) | |

| Figs. 4a, b: Augustus Fuller (1812–1873), Elizabeth Stone Denny and Edwards Denny, Worcester, Mass., 1840. Watercolor on ivory, 2¼ x 1¾ inches. Mr. Denny inscribed verso, “Augustus Fuller Deaf and Dumb artist 1840.” Private collection. Photograph by the authors. The oil-on-canvas portraits of the Dennys are shown in Figure 5. | ||

Aaron Jr., the older deaf son, was sent to the Connecticut Asylum in 1818, but his father’s difficulty in paying for his tuition meant that he stayed only two years. Meanwhile, interest in this new education prompted the Massachusetts Legislature to pass a bill in 1819 to establish a similar school. When the appropriated money was found to be insufficient, the funds were used to pay for Massachusetts children to attend the Connecticut school. This allowed both Fuller boys to attend the school in 1824, making them among the few fortunate deaf children to receive this special education.3 The students were also given extensive vocational training, with Augustus attending drawing and painting classes.

In late 1828, the sixteen-year-old Augustus had completed four years at the Asylum, and soon established himself as a portrait painter4 (Fig. 1). Although Augustus wrote with an extensive vocabulary and could communicate with his father and several siblings who had learned sign language, his family preferred that he travel with a relative because of the difficulties he faced when interacting with strangers. For the next several years he often traveled with his father while seeking portrait commissions. In an 1832 letter describing an itinerancy through New York State, his father wrote, “[W]hen we go into new places . . . they have a great curiosity, first to examine Augustus, they think there is some witchery in him and must take time to investigate that first.” Augustus added a postscript, “[M]y arms are lame in consequence of painting portraits . . . about $130 . . . I expect others - many more.” That same year, Augustus wrote from Fort Plains, New York, “have six portraits nearly done and good encouragement of eight or ten more at fifteen dollars each — children half price. At Clinton finished eighteen and should have stayed longer but the alarm of cholera that sent the inhabitants out in the country.” Newspaper advertisements always stated that he was a deaf and dumb artist, and he usually proudly added this phrase along with his signature to the back of his paintings.

---Elizabeth-Stone-Denny.jpg) | ---Edwards-Denny.jpg) | |

| Figs. 5a, b: Augustus Fuller (1812–1873), Elizabeth Stone Denny and Edwards Denny, Worcester, Mass., 1840. Oil on canvas, 30 x 24 inches each. Both inscribed verso, “January 20, 1840/Augustus Fuller,/Deaf and Dumb Mate.” Collection of the Worcester Historical Museum, Worcester, Mass. Photograph by the authors. The Dennys were classmates of Augustus Fuller at the Asylum in Hartford and similarly used Massachusetts state funds for this education. They hold writing implements showing that the Asylum’s specialized education taught them to read and write. | ||

As time progressed, Augustus increasingly traveled alone. From Chatham, Connecticut, he wrote, “I have the good opportunity to stay here to paint 5 to 7 portraits at no less than $10.00 each.” Occasionally, he received $25 for a large portrait “with hands.” He worked for a few months as a lithographer in New York City in late 1832, and wrote his parents, “I fear that you will take much trouble knowing where I am, Perhaps you thought I ran away!”

In 1833, his father “carried Augustus to Boston where [he] placed him with Mr. Harding, so he can be [a] better painter . . . He will remain for six or eight weeks to complete his education,” after which it was expected he would be “able to compete with Master Artists.” According to the surviving receipt, Chester Harding (1792–1866) charged $64.50 for the painting lessons.

Throughout his career, Augustus emphasized portrait miniatures on ivory and they represent the majority of his extant work (Figs. 2, 3, 4a, b). Several invoices describe that he purchased inexpensive ivory blanks with prices ranging from twenty to twenty-five cents. Portraits were also painted with oil on wood board or on canvas (Figs. 5a, b, 6, 7). Additionally, Augustus produced small watercolor on paper portraits of bust-length adults (Fig. 8) and full-length children, usually with toys, against a fully painted background (Figs. 9, 10).

Augustus was extremely proud of his profession, which allowed him to be self-sufficient. In 1836 he wrote to his parents, “Nothing is [more important than] the fact that manifesting the human ideas of beauty and natural colours . . . I seize the opportunity for honor and profession . . . now I am busily engage to paint portraits from life better than given . . . am much encouraged with customers.” The Boston Morning Post (Fig. 11) described Augustus as “A deaf and mute genius.”

|  | |

| Fig. 6: Augustus Fuller (1812–1873), Fanny Negus Fuller (1799–1845) with sons Francis Benjamin Fuller and John Emery Fuller, Deerfield, Mass., ca. 1838. Oil on canvas, 30 x 25 inches. The Charles P. Russell Collection, Deerfield Academy, Deerfield, Mass. Photograph by the authors. | Fig. 7: Augustus Fuller (1812–1873), Emily Merrill Bardwell (1809–1843), ca. 1840. Oil on canvas, 29 x 23 inches. Collection of Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Mass.; Gift of Barbara Hadley Stein, class of 1938. Photograph by the authors. |

Augustus wrote to his father in 1840 that “I am daily engaged in miniature painting . . . Happily for us to record many days with a glorious profession . . . perhaps I am yet a king or emperor of all arts, for taste and correct judgments . . . with painting for correctness of mind and character preeminent . . . They are foolish . . . for they think “Italy is proper for American beginners” NO! American is the first term for good portrait and landscape painters . . . I need not to Europe or Italy for I understand America is the best place to study [for] years . . . with A[merica’s] productions of the first order.”

In May 1840, Augustus and his younger brother George were in Boston and attended a daguerreotype demonstration, one of the first displays in America of this new process. George wrote to their father asking to borrow money, “you have heard much (through the papers) of the daguerreotype . . . Augustus and I went to see the specimens . . . Mr. Gouraud . . . will give me instructions for $10.00, and the apparatus will cost $51.00 making in all $61.00 only . . . I think anyone would give $7.00 for their perfect likeness. We could clear ourselves of all expenses in two weeks.”

On a trip together through upstate New York starting in December 1840, Augustus painted oil on canvas portraits for $10 and miniatures on ivory for $5, while George sold the novel daguerreotypes at $10 each. George wrote to their parents “people’s judging of painting I find it is regulated more by price than merit.” He suggested that Augustus increase his most expensive $20 portrait to $30. For the six-month trip, George recorded sixty-eight portraits by Augustus that produced $658.50, including $129 accepted as goods. Their expenses were $250.74, plus $50 sent to their parents. However, the technical difficulties of the early daguerreotype process resulted in George selling his new apparatus for a $20 loss and being “glad to get rid of it at that price.” Seeing the success of Augustus, George began his own painting career and would later become one of the most prominent artists in America. In 1841 George drew a likeness of his brother Augustus (Fig. 12).

|  | |

| Fig. 8: Augustus Fuller (1812–1873), Daniel Rice (1823–1900), Waterloo, N.Y., ca. 1835–1836. Watercolor on paper, 4 x 3 inches. Collection of the Memorial Hall Museum, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, Mass. Photograph by the authors. Daniel Rice became a famous circus clown and entertainer. This portrait was found in a pocketbook that also contained letters by Augustus Fuller. | Fig. 9: Augustus Fuller (1812–1873), Alexander Allen Cameron, probably Springfield, Mass., 1858. Watercolor on paper, 9 x 8 inches. Inscribed on front, “Augustus Fuller painter 1858” and “Alexander Allen Cameron.” Photograph courtesy of Charles Flint Antiques, Lenox, Mass. Collection of Historic Deerfield, Deerfield, Mass. |

As he traveled to a new location, Augustus sometimes found that the local economy was poor or that other portrait painters had recently visited. In 1842, a stage coach driver told him that there were so many portrait painters that “there are 6 painters in Haverhill, New Hampshire, who are now in ships fishing.” From Manchester, New Hampshire, he wrote, “I have many calls and don’t like the business because $10 is to little & unreasonable . . . People say there is no money.” When he was disappointed that his patrons would only agree to a low price he would call them “devilish charges.”

Getting paid was sometimes a problem. Having painted three portraits for a Mr. Dickinson and expecting $25 dollars, Augustus was unwilling to accept $13 in cash and the balance in goods from Dickinson’s store. In another letter he recounted how “one rascal has told me lies, for the purpose of finishing 7 portraits for $42, but he was put in jail for cheating money with some lady, said he wanted to learn an art of portrait painting . . . he was a house painter.” In a letter to George in 1843, Augustus explained that he did better in the country than in urban areas. “[T]he Bostonians do not pay me the whole, I feel obliged to the counties. They give me money quickly.”

Letters often expressed concern about Augustus and his problems with alcohol. As early as 1840, George Caldwell, a deaf-mute friend, wrote to his father, “I think you should take him home because he will continue to be drunk all the times . . . he often goes to some bad houses and pay[s] his own money to girls . . . one gentleman was insulted by him in [the] street and almost struck him with his cane . . . He told me he drank 17 glasses of brandy per day . . . I think he shall ruin himself by drinking to excess.” On several occasions, Augustus wrote to family members promising abstinence, “you may know that I have pledged cold water Temperance . . . Portrait Painters should be very careful never dally to destroy this sacred tribute of respect and profession.”

Augustus experienced intolerance from many quarters. The Boston Daily Bee reported in 1846 that bystanders had brought an assault case against a boy “for throwing stones at Augustus Fuller and otherwise assaulting him . . . Fuller is a deaf and dumb man.” Yet his business continued to thrive and one of his brothers noted that “Augustus came home this week in good health & spirits drove to death with business staid [sic] only two days.”

| |

| Fig. 11:Boston Morning Post, Boston, Mass., August 12, 1840. |

In December 1850, Augustus was sentenced to six months imprisonment in the Hampden County House of Correction, Springfield, Massachusetts, “for selling obscene prints.” When his crime was reported in newspapers throughout New England, there was much consternation amongst the family members. In a letter to George, Augustus explained “know that I painted fancy pictures for my friends, never know anything against the law but obey it.” He claimed that he did not understand the proceedings and was tricked when the clerk of the court made a “G” with his finger, after which Augustus also made the sign. The clerk then told the judge that he had pleaded guilty. From jail, he bitterly complained that he was put to work as a shoemaker. “I work hard like a slave . . . God Pity the poor, ignorant and deaf mute . . . .”

|  | |

| Fig. 10: Augustus Fuller (1812–1873), Mary Ella Childs holding Lilla, Deerfield, Mass., ca. 1863. Watercolor on paper, 9 x 7.1 inches. Collection of the Memorial Hall Museum, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, Mass. Photograph by the authors. This portrait descended in the Fuller family until donated to the Memorial Hall Museum. | Fig. 12: George Fuller (1822–1884), Augustus Fuller, 1841. Pencil on paper, 7 x 6 inches. Inscribed “Drawn by GB Fuller of A. Fuller Sept 11th 1841.” Fuller-Higginson Papers, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library, Deerfield, Mass. Photograph by the authors. |

George wrote to their father, “Perhaps a little punishment may be beneficial to him . . . it is mortifying enough but I do not know that we have neglected anything in our power for his welfare.” After the jail sentence, Augustus spent increasing amounts of time at the family farm in Deerfield while continuing to make painting trips. Letters between family members described him being “so taken up with the fine arts as to be of no use at home” and that “he rises early & paints by lamp light.” In 1859, when his father died, Augustus received only a token payment of $50.

As his health began to fail in the early 1870s, Augustus expressed regrets for missed opportunities. “[I] would have liked much money for traveling thro London, Paris (France) & Rome in Italy perhaps Egypt and Africa myself alone [or] with many portrait painters of eminence and great talents . . . but they can never ever beat me because I am always deaf-mute person and used it to become celebrated.” Augustus Fuller died on August 12, 1873. His aunt, Caroline Negus, had reminisced, “I often think of him & dwell on those old days when he was as gay and graceful as a fawn, & when he was admitted by all to be the most fascinating of boys - I will never cease to regret his being deaf & dumb.”

Michael R. Payne, Ph.D. and Suzanne Rudnick Payne, Ph.D. research early American folk artists. This is the fourteenth article they have published on early American painters. They would like to express their deepest gratitude to David Bosse, Librarian, Historic Deerfield, and Suzanne Flynt, Curator, Memorial Hall Museum, Deerfield, Mass., for their unfailing help.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

1a. The first school for the deaf in America was Braidwood Academy for the Deaf in Enon, Virginia. Braidwood started as a school for private deaf tutoring from 1812 to 1815. In 1815, it opened in a different location as a public deaf school, closing in 1816. It reopened in May of 1817 in a third location and continued in operation until 1821. American School for the Deaf is the second school in America, though the oldest permanent school still in operation today. (Source: Kathleen Brockway, deaf historian.)

2. The information and quotes in this article are from the Fuller-Higginson family papers, Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association Library, Deerfield, Mass. The authors have examined all of the documents concerning Augustus Fuller amongst the over 30,000 items in this family archive. For additional Augustus Fuller paintings, see Caroline F. Sloat, editor, Meet Your Neighbors: New England Portraits, Painters & Society, 1790–1850 (Amherst, Mass.: Old Sturbridge Village, 1992).

3. Another folk portrait painter, John Brewster Jr. (1766–1854), also attended the Connecticut Asylum. Brewster did not attend the Asylum at the same time as Augustus Fuller.

4. We have located numerous 1830 receipts for portraits at $5.00, the purchase of wood boards for paintings at 25 cents, and several advertisements in the nearby Greenfield, Massachusetts, newspaper.