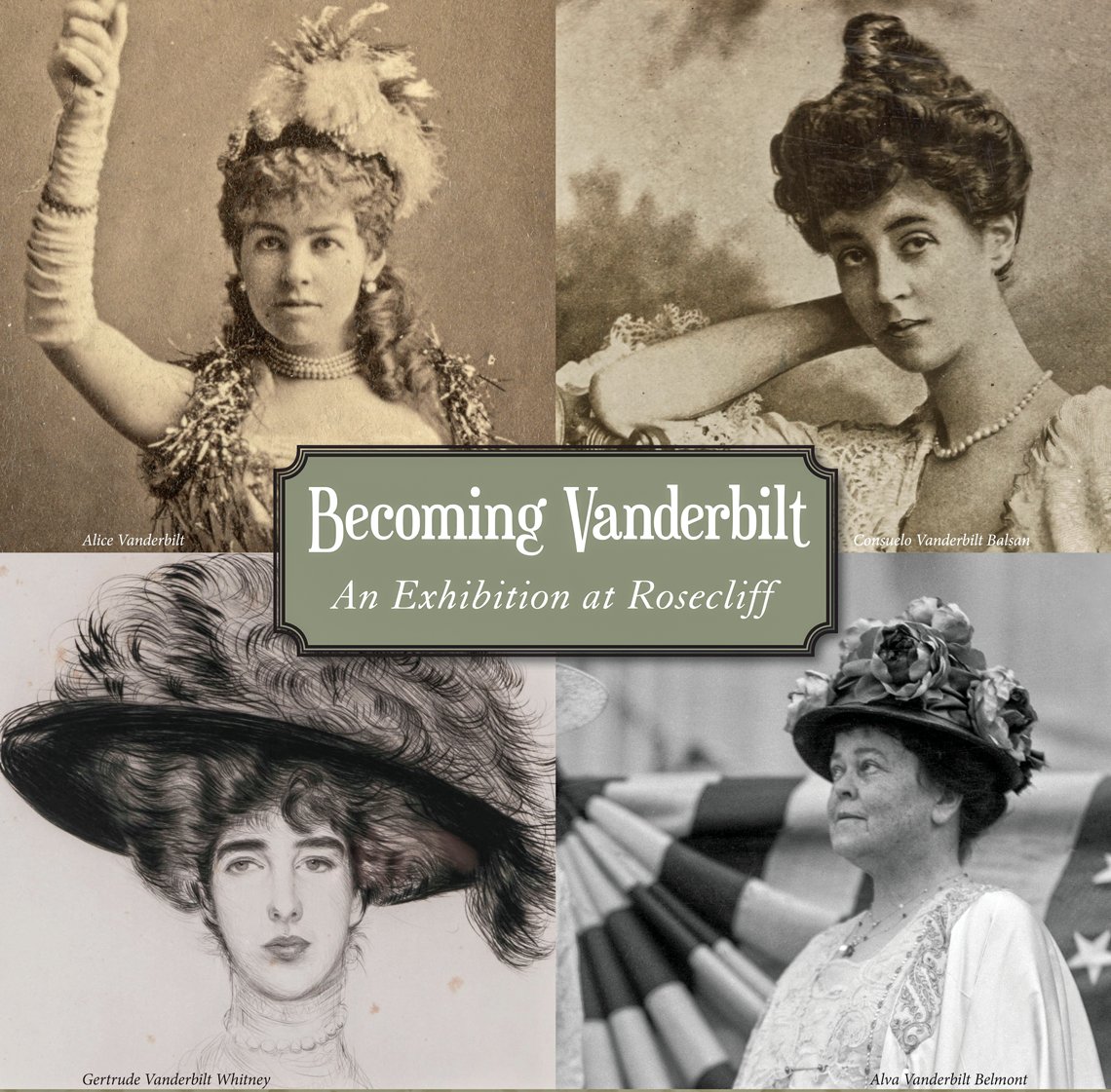

Becoming Vanderbilt: An Exhibition at Rosecliff

Preservation Society of Newport County

|

The Preservation Society of Newport County’s Becoming Vanderbilt: An Exhibition at Rosecliff, is a celebration of four extraordinary Vanderbilt women associated with the Gilded Age Newport Mansions. Planned to coincide with the one hundredth anniversary year of women’s right to vote, the opening was delayed in mid-March because of the COVID-19 pandemic. A virtual 3D tour was created and shared on NewportMansions.org, and the exhibition itself opened to the public in early September.

A wide range of objects large and small, public and intimate, from the Preservation Society’s collections, as well as loans from other institutions and private collections, illustrate the lives and legacies of Alice Claypoole Gwynne Vanderbilt, philanthropist and matriarch of The Breakers; her daughter Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, patron, artist, and founder of the Whitney Museum of American Art; Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, creator of Marble House and important advocate for women’s suffrage; and her daughter Consuelo Vanderbilt Balsan, who became Duchess of Marlborough and benefactor of many causes, including less-fortunate women and children.

By showing personal effects, clothing, and memorabilia, and sharing narratives of their lives and works, the exhibition aims to provide a deeper perspective on these women, their passions, and personalities, and the spirit of the times in which each navigated her own path. For tickets, exhibition times, and more information, visit www.newportmansions.org/exhibitions

|

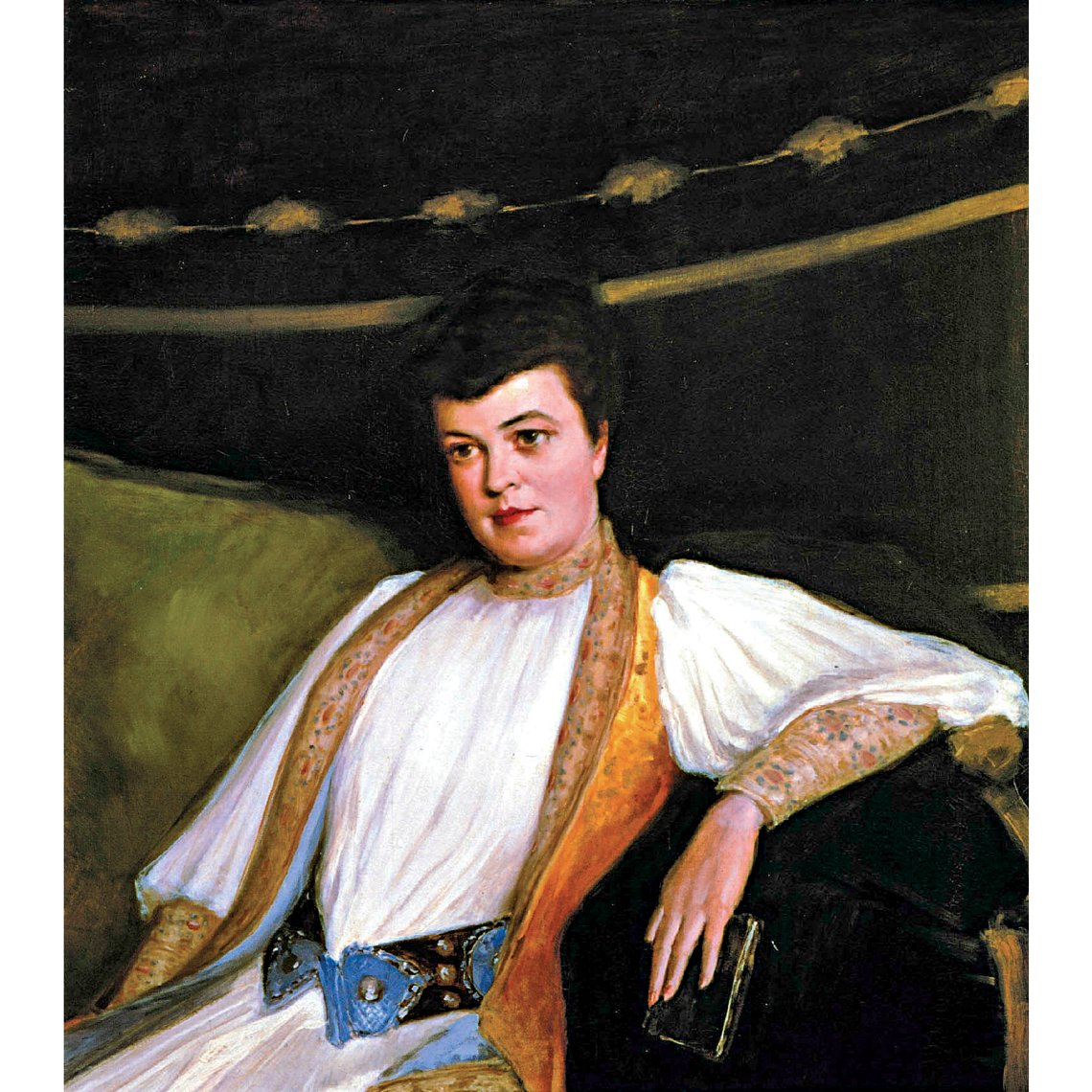

This painting by Spanish artist Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (1841–1920) portrays Alice Claypoole Gwynne Vanderbilt (1845–1934), wife of Cornelius Vanderbilt II (1843–1899), who built The Breakers. It was painted while she and her family were on a summer trip to Europe in 1880, when she was thirty-five. Alice appears contented during what was a happy period of her life. She had already lost a daughter, her namesake, to scarlet fever, and more tragedy was to follow over the next several decades, as she survived the loss of her husband and three more children.

|

A bronze cast of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s right hand, by an unknown maker in the first quarter of the twentieth century, offers an intimate physical impression of the artist and sculptor. Gertrude (1875–1942) grew up summering at The Breakers, and her bedroom there displays several of her works, as well as original furnishings. The hand cast is mentioned by Flora Miller Biddle, Gertrude’s granddaughter, in her memoir The Whitney Women and the Museum They Made, where she described Gertrude’s “long and graceful hands with hard nails shaped like almonds and painted scarlet.” The bronze hand, she wrote, “sits on a table in our bedroom, looking, I imagined, like that of an artist.” Courtesy of The Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney Studio, Old Westbury, N.Y.

|

Gertrude was especially noted for her sculptures, including war monuments, such as the American Expeditionary Forces Memorial (dedicated in 1926) in Saint-Nazaire, France, which depicts a World War I doughboy standing atop an eagle, with sword in hand. In the exhibition are a realist bust of her husband, Harry Payne Whitney (bronze, 1906); a maquette of her sculpture Chinoise, the only self-portrait she is known to have made (terracotta, 1913); and Barbara, a realist portrait of her youngest child at age ten (bronze, 1913). All on loan from The Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney Studio, Old Westbury, N.Y.

|

This is the wedding dress worn by Gertrude for her marriage to Harry Payne Whitney (1872–1930) on August 25, 1896, at The Breakers. In satin with organza panels, it was designed by Jacques Doucet in 1895. The wedding was a small affair for the Vanderbilts, limited to only sixty guests because of her father Cornelius’ stroke only one month before. Also displayed is the headdress of tulle, satin, and paper orange blossoms that Gertrude wore for the occasion, and which had been worn by her mother, Alice, when she married Cornelius in 1867.

|

This portrait by an unknown artist of Alva Vanderbilt (1853–1933) was painted in the 1880s, when she was in her thirties and married to William Kissam Vanderbilt (1849–1920). It conveys her strong, determined character. Alva was born in Mobile, Alabama, to a family whose fortunes were largely decimated by the Civil War. She made herself a central figure in New York and Newport society in the Gilded Age, and commissioned Marble House in Newport in imitation of the grand palaces of France.

|

Alva, right, and Consuelo (1877–1964), her daughter, are shown in a photograph from one of the many suffrage rallies Alva hosted at Marble House. She used her social position and the spectacular setting of her Newport “summer cottage” to raise money and enthusiasm for the cause. The relationship between mother and daughter was sometimes tense—Alva was domineering and forced Consuelo into a loveless marriage to the English Duke of Marlborough—but here they stand proudly side by side, representing women’s aspirations for political rights.

|

These original “Votes for Women” tableware and suffrage pamphlets are artifacts of the activism of Alva Vanderbilt Belmont. Alva designed and ordered the porcelain table service from John Maddock & Sons Ltd., for use at her “Conference of Great Women” rally at Marble House during the summer of 1914 (see the photograph taken of her and Consuelo at the conference). All the proceeds from ticket sales were donated to the women’s suffrage cause.

|

On loan from the Blenheim Palace Heritage Foundation are two articles of clothing that illustrate the elegance of Consuelo’s life as a duchess. At left is a reproduction of a dress she wore in the family portrait by John Singer Sargent, painted in 1905, which still hangs in Blenheim Palace. The black silk and rose satin reproduction was handmade by Ally Baker in 2016. At right is the original suit worn by her younger son, Lord Ivor Spencer Churchill, to the coronation of George V in 1911. Its eighteenth-century style was customary in formal court ensembles for boys of Ivor’s age and class.

|

Also from Blenheim Palace, this traveling trunk belonged to Consuelo, and has her initials “C. M.” on the lid. Made around 1895, the trunk shows signs of extensive use with its many scuffs, nicks, and scratches.

|

These are the master keys to Blenheim Palace that belonged to Consuelo Vanderbilt when she was the Duchess of Marlborough. Consuelo initially had some difficulty being taken seriously by British aristocrats, but she soon earned respect. She used her wealth and social prominence to help the less fortunate, starting with the poor tenants on her husband’s estate. She was particularly devoted to the welfare of poor mothers and children, persuading London leaders to provide a playground for children and establishing a “Children’s Jewel Fund” that collected donations of jewelry to support more than 160 child welfare centers during World War I.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2020 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|