Breaking Down Barriers: 300 Years of Women in Art

This archive article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2011 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

Art history has long been dominated by male artists. A number of factors prevented women from achieving artistic prominence,1 primary among them was the fact that until the nineteenth century women were denied entrance to schools and academies, and even then they were not permitted to work from nude models. And while opportunities for women began to expand in the late nineteenth century, social pressures continued to discourage women from pursuing a career in the arts. Encouraged to dabble in drawing and painting as part of a well-rounded education, women were expected to become full-time wives and mothers—an expectation that continued well into the twentieth century.

Breaking Down Barriers: 300 Years of Women in Art at the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston, South Carolina, explores the lives and works of a number of female artists who were among the notable exceptions in a male dominated profession and whose work is now in the collection of the Gibbes Museum. The story begins with Henrietta Johnston (ca. 1674–1729), recognized as the first female professional artist in America. The European-born Johnston moved to Charleston in 1708 when the Church of England’s Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts appointed her husband, Gideon Johnston, commissary for South Carolina. Facing considerable financial hardships in Charleston, Henrietta helped support her family by creating pastel portraits of social acquaintances and members of her husband’s congregation. “Were it not for the assistance my wife gives me by drawing pictures…I shou’d not have been able to live,” 2 her husband wrote in a letter to the Society in 1709. Works by Johnston entered the Gibbes collection as early as 1920, and the museum houses the largest public collection of her work (Fig. 1).

Another significant eighteenth-century female artist in the Gibbes collection is Angelica Kauffman (1741–1807) (Fig. 2), whose skills as an artist were evident at an early age. Kauffman was able to overcome the lack of educational opportunities for women by receiving training from her artist father, a recurring theme among the few successful female artists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As a young girl, she and her family moved from Switzerland to Italy, where her travels with her father allowed her to study classical sculpture and the paintings of the Old Masters. She spent countless hours copying such works in Milan, Florence, and Rome; an opportunity few women had in eighteenth-century Europe. After a brief first marriage, her second husband was supportive of her career as an artist and she continued to paint.

Beyond Johnston and Kauffman, few women artists of the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries are represented in the Gibbes collection, which is typical of many American museum collections. Of these early American artists, both Mary Roberts (d. 1761) and Louisa Strobel (1803–1883) painted portrait miniatures, a genre deemed appropriate for refined, educated women. Roberts is notable as the first woman miniaturist in America (Fig. 3), and also the first American to paint portrait miniatures on ivory. She painted numerous miniature portraits of the prominent Middleton family of Charleston; each painting measuring a miniscule one and a half inches in height. Like Henrietta Johnston, Roberts was a European who settled in Charleston, garnering support for her work from her husband, a fellow artist. Louisa Strobel did not paint professionally and only created portraits of family members and friends. Upon marrying the Reverend Benjamin Martin in 1841, Strobel stopped painting—perhaps to assume her “proper” role as wife, and eventually, mother.

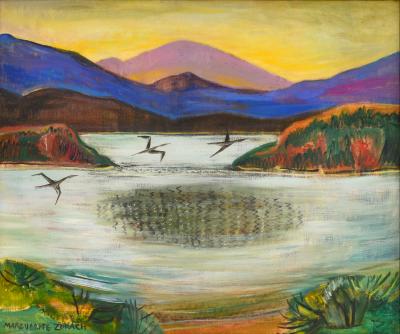

Women artists are better represented in the museum’s twentieth-century holdings. In large part, this is due to the great number of women involved in what is known as the Charleston Renaissance, which occurred between the two World Wars, when the city experienced a resurgence in literature, music, historic preservation, and the visual arts. Among its leaders were Alice Ravenel Huger Smith (1876–1958), Elizabeth O’Neill Verner (1883–1979), and Anna Heyward Taylor (1879–1956). All three created numerous works depicting the architecture and landscape of Charleston and the surrounding Lowcounty region. Smith is best known for her series of thirty watercolor paintings entitled A Carolina Rice Plantation of the Fifties, which includes the circa-1935 painting A Lagoon by the Sea (Fig. 4). Verner created numerous etchings of downtown Charleston in the 1920s and 1930s; later in her career she focused on pastels (Fig. 5). Together, the women of the Charleston Renaissance helped shape public perception and bring national attention to the city’s historic charm and its rich cultural heritage.

During the same time period, a number of significant women photographers were employed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which sent millions of unemployed Americans, including more than 5,000 artists, back to work during the Great Depression. Under the auspices of the WPA’s Federal Art Project, Berenice Abbott (1898–1991) photographed the architecture of New York City for an ambitious project entitled Changing New York (Fig. 6). Prior to that, Abbott had traveled to Charleston during the summer of 1934, after she was hired by architectural historian Henry-Russell Hitchcock to photograph Civil War-era architecture in Charleston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Boston.

Photographer Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971) also traveled through the South in the 1930s. Like many of the famed photographers of the era, Bourke-White worked in a documentary style to capture the devastating effects of the Great Depression (Fig. 7). Bourke-White was one of the first women to break into the male-dominated field of photojournalism. In 1929 she was hired as the first staff photographer for Fortune magazine. In 1936 she was hired as the first female photojournalist for Life magazine and one of her photographs appeared on Life magazine’s first cover in 1936. Throughout her career Bourke-White broke records: she was the first Western photographer allowed into the Soviet Union, and the first female war correspondent during World War II.

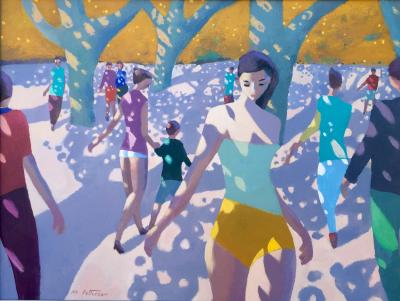

On the heels of World War II, the focus of the art world shifted for the first time from Europe to America, where Abstract Expressionism flourished in New York City from the mid-1940s through the 1950s. Dominated by artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Robert Motherwell, women like Lee Krasner and Joan Mitchell also participated in the movement, but received relatively little recognition. Though Charleston remained a stronghold of traditional artistic styles, a number of artists broke with tradition; among them was Corrie McCallum (1914–2009). Though she and her family chose to settle in Charleston, McCallum followed the development of Abstract Expressionism and incorporated the style into her work. McCallum’s circa-1965 painting View of Toledo (Fig. 8) retains recognizable subject matter but demonstrates her interest in abstraction through her gestural brushwork and reduction of forms.

In addition to her vast body of work, McCallum made significant contributions to the Charleston art community as an educator; another common theme among women artists, many of whom taught in order to support themselves and their families. McCallum held education positions at several institutions, and throughout her life remained an outspoken advocate for the visual arts. Artist Virginia Fouché Bolton (1929–2004) was an arts educator in the Charleston area known for her dedication to her students (Fig. 9).

Today, a number of significant women artists work in Charleston and contribute to its thriving art community. Mary Jackson (b. 1945), a 2008 MacArthur Foundation Fellow, is a nationally recognized master of sweetgrass basketry. Brought to America from West Africa during the early days of slavery, the art form has been in continuous production since the eighteenth century and is considered one of the oldest art forms of African origin in America today. Providing a link to African heritage, Jackson learned the art form from her mother and grandmother and is known for her highly inventive forms (Fig. 10).

Among the younger generation working in the city is Jill Hooper (b. 1970), an artist grounded in the techniques of the Old Masters, who paints from life with natural light and mixes her own pigments (Fig. 11). Engagement with her subject matter is essential to Hooper’s process and carries through in her finished work—whether it be the psychological intensity conveyed by a sitter or the delicate balance between life and death communicated through the decaying fruit of a still life. Hooper gained notice at an early age, and in 2000, at the age of thirty, she became the youngest living artist to be included in the Gibbes collection.

As evidenced by the Gibbes collection, museums have played a crucial role in preserving work created by women and in helping to advance the careers of contemporary female artists. The work being created today by women artists in Charleston and throughout the United States stands as a testament to the women of past generations who defied convention and paved the way for women to achieve success as professional artists.

Breaking Down Barriers: 300 Years of Women in Art, was on view October 28, 2011, through January 8, 2012, at the Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, South Carolina. For information call 843.722.2706 or visit www.gibbesmuseum.org

Pamela S. Wall is the curator of exhibitions at the Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, South Carolina.

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2011 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afa.mag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Quoted in Martha R. Severens, “Who Was Henrietta Johnston?” The Magazine Antiques CXLVIII, no. 5 (November 1995): 707.