Breaking the Mold: The American Folk Art Museum’s Bright Future

The most pressing agenda item for the American Folk Art Museum’s (AFAM) 2012 Strategic Plan was to find a director. With Anne-Imelda Radice, the museum got their wish—in spades. Within her first month, Radice successfully approached the Luce Foundation to fund a traveling exhibition to prove AFAM was alive and thriving: Self-Taught Genius: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum. Opened in 2014 at AFAM, the show will complete its national tour in January 2017. The run has included six additional museum installations that inform, entertain, and educate visitors about the changing nature of self-taught art, material for which the museum is renowned.

Radice has been a whirlwind since arriving, stating, “I wanted to break the mold of the AFAM of the past.” The past to which she refers involved a crushing debt resulting from the museum’s presence on West 53rd Street, in an 82-foot-high building designed in 2001 by Tod Williams and Billie Tsien for the museum’s exhibition spaces and offices. Though strikingly sculptural with its nonconformist, undulating copper-bronze façade, and an ode to contemporary architecture, the interior spaces did not lend themselves to exhibitions and the museum was unable to draw the expected crowds, even with its location alongside MoMA. Expenses mounted and AFAM sold the property in 2011 to the neighboring museum.

The resulting chatter was that AFAM would not survive. Fingers were pointed and questions arose about the future of the collections. Determined to keep the museum solvent, AFAM’s board and staff rolled up their sleeves and, unburdened by the financial behemoth of 53rd Street, moved their headquarters back to property they’d maintained in Lincoln Square, across from Lincoln Center and the Metropolitan Opera House. An interim strategic plan was drawn up in 2012, and when Radice started her tenure in September of that year the budget was minimal, with only a few million in the endowment. With determination from all parties and adjustments to its staffing, the museum has been operating in the black for the past few years, with a budget holding steady at $3.3 to $3.5 million. Fifty-four years after it was founded, the museum is starting fresh, by breaking with its recent past.

Radice, an outsider hailing from Washington, D.C., holds three advanced degrees, one of which is an MBA in finance, which an early mentor, Carter Brown of the National Gallery of Art, suggested she pursue if she wanted to reach her goal of being a museum director. Her career path has included director of the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS); acting chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts; chief of staff at the U.S. Department of Education; (the first) director of the National Museum of Women in the Arts; curator in the Office of the Architect of the Capitol; and an assistant curator at the National Gallery. As a member of AFAM at an earlier point, she was aware of the collection, its exceptional curatorial staff, and its strong public programs, so when the director position came open, she jumped at the opportunity to offer her business acumen and political and arts world connections to the museum.

- Flag Gate, Artist unidentified, Jefferson County, New York, United States, ca. 1876. Paint on wood with iron and brass, 39-1/2 x 57 x 3-3/4 inches. American Folk Art Museum, New York; Gift of Herbert Waide Hemphill Jr. in honor of Neal A. Prince (1962.1.1). Photo by John Parnell. This was the first object to enter the museum’s collection.

With her zest for the arts and passion to see AFAM thrive, Radice, in tandem with the board and staff, has been working to make the collections accessible across local and national markets; building the museum’s scholarly reputation; serving diverse audiences and expanding the range of exhibitions; and strengthening the museum’s assets (board, staff, collections, membership, facilities), its fundraising initiatives, and project-based revenue.

Her first priority was the collection, which numbers more than 8,000 pieces of artwork, from textiles to paintings to three-dimensional objects to works on paper. Partially stored in Brooklyn or on loan to other institutions, while the collection was being kept in climate-controlled conditions, the archives were relegated to boxes; a solution needed to be found. A 17,500-square-foot building was located in Long Island City, Queens, and renovated to include HVAC, security, offices, storage space, and a library and reading room overseen by librarian Louise Masarof. Rapaport archivist, Mimi Lester is the museum’s first named position. Says Radice, “An archivist is a key position because it sends the message that what’s important to us is our collection.” The Collections and Eduation Center (CEC), which opened in early 2015, also has gallery space, with exhibitions that change several times per year—an exhibition on quilts is currently on view.

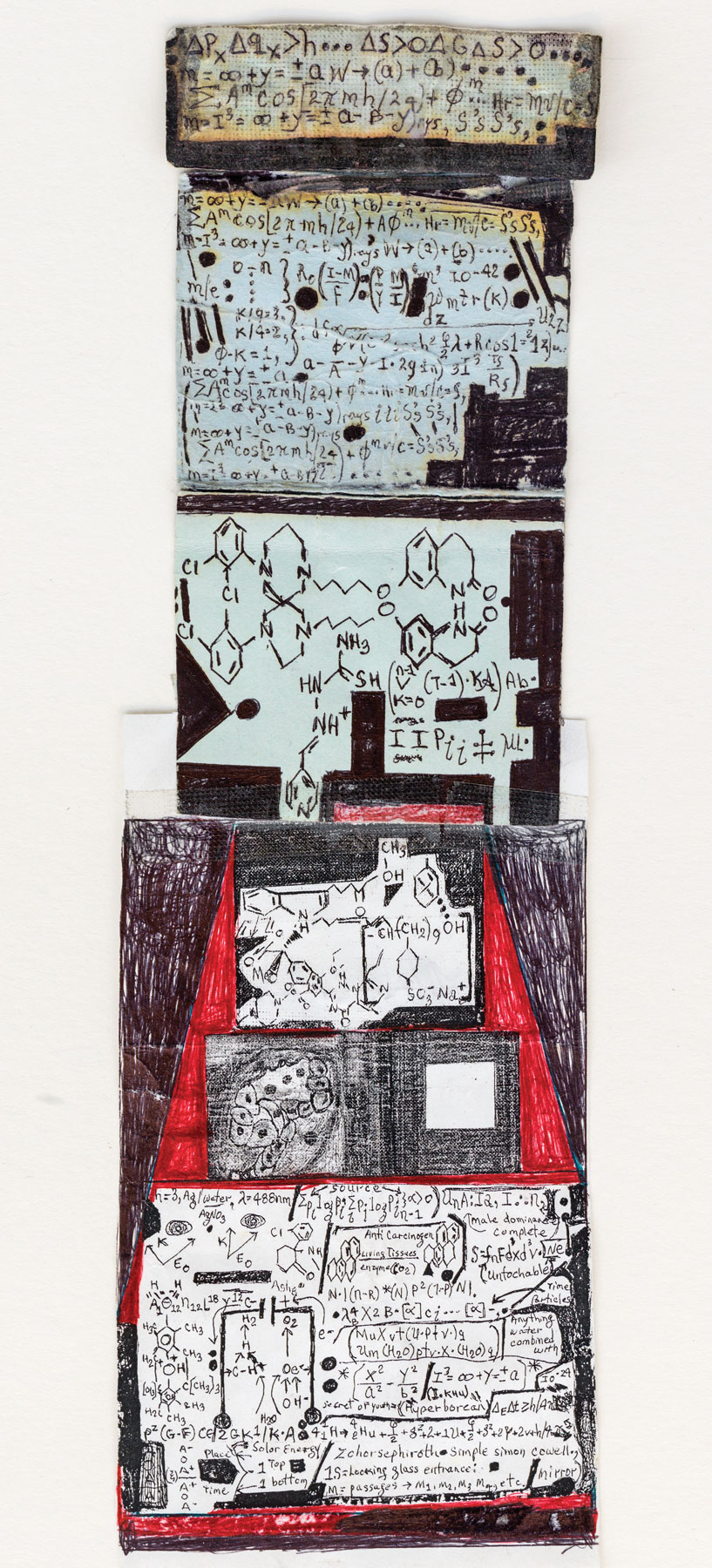

AFAM’s curatorial staff was also increased. Stacy Hollander, who was made deputy director of curatorial affairs, has been joined by Dr. Valérie Rousseau, who oversees the self-taught and art brut collections. Their exhibitions have attracted national and international attention, with a show Dr. Rousseau curated—When the Curtain Never Comes Down—being named by The New York Times as one of the ten best of the year in 2015.

In addition to being an important vehicle for collections exposure, the Center also helps build community outreach. “We are working on a children’s book, to be published in English and Arabic, which is a direct result of responding to our varied audiences in Queens,” says Radice. “The original artwork from the book will be exhibited in the CEC gallery.” In addition, Radice has reached out to the Mellon Foundation with a proposal for a program for young people interested in a museum career but without the resources to pursue one. She successfully initiated a partnering project with LaGuardia Community College (in AFAM’s Long Island City neighborhood). “We just finished our first year of the paid internship program,” she states proudly. “One student just got a scholarship to Hunter College and she’s interested in pursuing conservation.”

Tasked with “getting the art out,” Radice’s next step was to develop a five-year exhibition plan. The Ford Foundation helped the museum explore how best to sync exhibitions with educational opportunities and, in a continual effort to stay relevant and connected with audiences, AFAM conducts regular visitor surveys that help guide decisions, such as keeping exhibitions installed for longer periods of time. “We have the right mix,” notes Radice, “alternating our shows between traditional folk art and self-taught art. An exhibition on the work of Ronald Lockett, an artist from recent past, just closed,” she says. “And Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America, recently opened; it will be followed by a show on the work of self-taught artists Carlo Zinelli and Eugene Gabritschesky.”

Other museum outreach projects include traveling exhibitions, such as the already noted Self Taught Genius, and loan shows. “Crystal Bridges Museum of Art approached us,” says Radice, “and suggested we do a show for them, American Made: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum” (July 2–September 18, 2016). “This exhibit marked the first folk art exhibition held at Crystal Bridges, and they organized strong programs around it.” Radice adds, “We hope to partner with them again in the future.” It’s creativity like this that will keep AFAM in the forefront of people’s minds. Creativity and gumption to take risks, such as a show AFAM sent earlier this year to the Huntsville Museum of Art: Folk Couture: Fashion and Folk Art, the likes of which had never been previously undertaken. A natural at forging strategic partnerships, Radice enlisted the help of the head of New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in finding a co-curator for the show along with AFAM curator Stacy Hollander. The result was stellar and, along with the other outreach successes, focuses on the types of attendance-building that AFAM will continue to expand.

|

|

Another way the museum enhances its profile and draws an audience is with free admission. Written into the contract for the Lincoln Square location, the museum cannot charge an entry fee. Though they forgo the added revenue that admission would bring, foot traffic is breaking records, and Radice and her staff have created other revenue generators such as the museum store, described as “one of the world’s best museum gift stores” by Conde Nast Traveler. Located by the museum entrance, the shop generates nearly as much revenue as is “lost” to free admission. AFAM also takes advantage of its location across from Lincoln Center by staying open until 7:00 p.m., attracting not only the opera crowd but people looking for after-work activities, as well as younger people, who, more and more, are looking to incorporate museums into their social schedules. It’s up to museums to recognize this phenomenon and respond to it. AFAM has heard the call to action and is expanding its profile through social media and a video presence online, as well as with dynamic programs for “Young Folk” in their twenties and thirties, Jazz Wednesdays and Free Music Fridays, and various other creative membership events. AFAM also expands into areas that help people with medical conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease. Says Radice, “Folk, self-taught, and art brut is by nature inclusionary. What we show is high quality art that is approachable by everyone, and we do so in an engaging and diverse manner.”

Success with efforts to drive up attendance numbers, improve visitor experience (both at the two locations and with the many online features), create diverse and educational programming with an emphasis on scholarship, expand outreach, and increase marketing, all translate to AFAM’s being a leader in the museum community; made even more impressive by the fact that it’s all done with a relatively small staff of twenty-one and within budget.

The museum’s fiscal strength is achieved by a combination of an active board and Radice’s fundraising skills. With goals of expanding the endowment and unrestricted funds (as well as estate planning and other gifting opportunities), the director is continually making connections and asks the same of the board and staff, reinforcing the value of maintaining a visible profile on the local and national scenes. “As ambassadors of the museum, we want to engage people in what we are doing and let them know that they will make a difference. The hard sell approach doesn’t work for me; I don’t want people to run when they see me,” she says. “Timing is important—you have to make your request special and relevant to their interests.” She adds, “It’s all about relationships.”

AFAM has come a long way in four years. Radice and those involved with the museum are energized by how it has turned a corner, in large part due to AFAM’s loyal and growing community of supporters. Such trust would not be possible, however, without the progress made, in large part due to the director’s vision and ability to encourage teamwork and create a culture of support and success. As chairman of the board Monty Blanchard noted when hiring Radice, “We believe she is the ideal person to lead us.”