Caribbean Houses

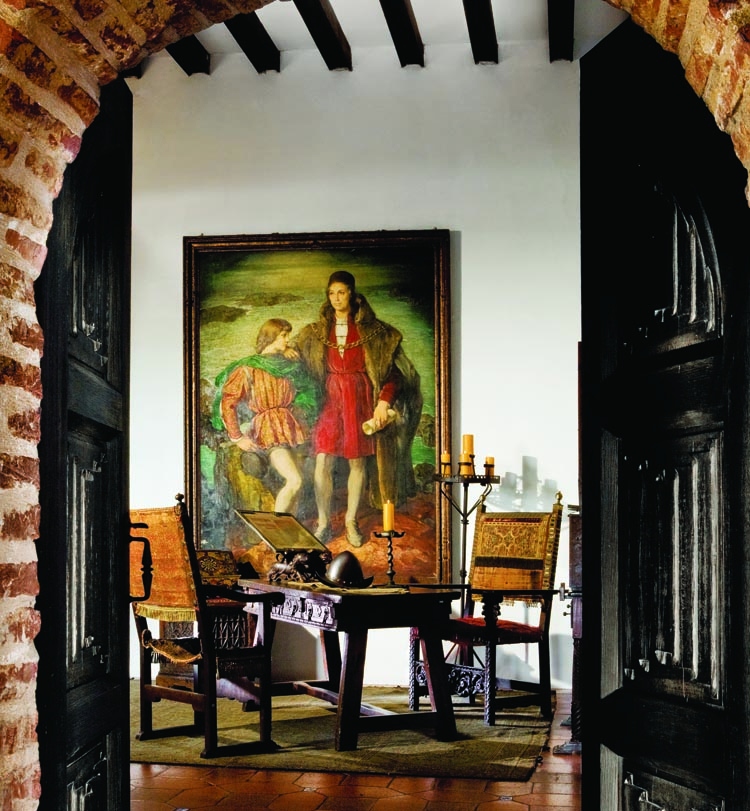

- Fig. 2: A portrait of Christopher Columbus and his son Diego Colón hangs in the library of the Alcázar. The majority of furniture, decorative arts, and fine art in the palace today, although not original to the house, dates from the period. Most of the pieces are sixteenth or seventeenth century and of Spanish origin.

Architecture is one of the most universal accomplishments of humankind, one that arises from the basic need for shelter. Because of its ubiquity, it has long been the focus of much study and documentation. Yet, Caribbean architecture is a relatively new field, and its history has seldom been recorded. The fragmentary bits of literature and research on the subject, and more specifically on historically significant residences, completely lack detailed descriptions, definitive analysis, or aesthetic focus. Early travelers to the islands who recorded their observations wrote primarily about botany, geology, and zoology; only rarely did they reflect or comment on the architecture they observed. Twentieth-century comprehensive literature focuses on military, religious, civil, and educational structures. The study and documentation of domestic architecture, especially the plantation houses and grand urban palaces, has been largely ignored prior to this point.

The Spanish

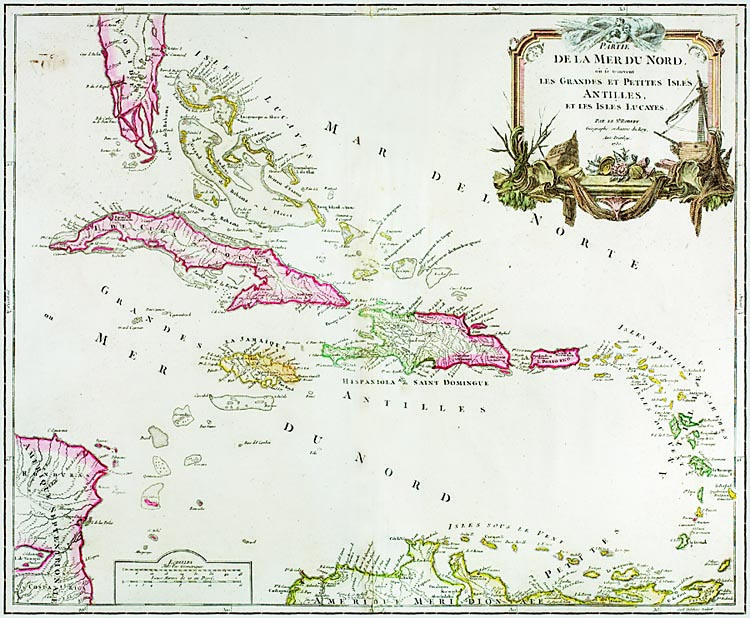

- A hand-colored map titled “De la Mer du Nord, les Grandes et Petites Isles Antilles” by Robert Du Vaugondy. Engraved in 1750, it was published in Paris in Du Vaugondy’s 1757 Atlas Universal. The Caribbean islands form an archipelago separating the Caribbean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean; they are more than thirty islands arranged in a wide arc stretching from Cuba, off the coast of Florida, to Aruba, off the Venezuelan coast.The era of European colonization in the Caribbean began with the Spanish in the last decade of the fifteenth century. Although constantly harassed by French and English privateers, Spain dominated the West Indies and monopolized New World wealth until the late sixteenth century. The first palatial houses in the West Indies were constructed on the Spanish island and were influenced by the styles then popular in Spain. The symmetrical lines of the architecture corresponded with Renaissance designs, and the houses sometimes assimilated Mudéjar, or Hispano-Moorish, patterns and construction techniques. Named for the Moors (Muslims) who remained in Spain after the Christian reconquest, Mudéjar is the term used to describe the fusion of Moorish and Spanish-Christian influences, which is characterized in architecture by arches, intricately carved woodwork, and balconies.The first Spanish colonists settled in Santo Domingo, which is today the capital of the Dominican Republic, the country that shares the island of Hispaniola with Haiti. Columbus had named the island Hispaniola La Isla Española because it reminded him of Spain; the name was later corrupted to Hispaniola. Early colonial domestic architecture ranged from the Alcázar, Diego Columbus’s house built in Santo Domingo in 1510, to the Cuban home and headquarters of Spanish conquistador Diego Velásquez de Cuellar, constructed in 1511.

The era of European colonization in the Caribbean began with the Spanish in the last decade of the fifteenth century. Although constantly harassed by French and English privateers, Spain dominated the West Indies and monopolized New World wealth until the late sixteenth century. The first palatial houses in the West Indies were constructed on the Spanish island and were influenced by the styles then popular in Spain. The symmetrical lines of the architecture corresponded with Renaissance designs, and the houses sometimes assimilated Mudéjar, or Hispano-Moorish, patterns and construction techniques. Named for the Moors (Muslims) who remained in Spain after the Christian reconquest, Mudéjar is the term used to describe the fusion of Moorish and Spanish-Christian influences, which is characterized in architecture by arches, intricately carved woodwork, and balconies.

The first Spanish colonists settled in Santo Domingo, which is today the capital of the Dominican Republic, the country that shares the island of Hispaniola with Haiti. Columbus had named the island Hispaniola La Isla Española because it reminded him of Spain; the name was later corrupted to Hispaniola. Early colonial domestic architecture ranged from the Alcázar, Diego Columbus’s house built in Santo Domingo in 1510, to the Cuban home and headquarters of Spanish conquistador Diego Velásquez de Cuellar, constructed in 1511.

The Alcázar

Sometimes called the Columbus Palace, the Alcázar de Colón (Fig. 1) was constructed of massive blocks of cut coral limestone to house Diego Columbus, son of the explorer (Fig. 2), and his aristocratic wife, Maria de Toledo. Completed in 1510, it was the Columbuses’ family home until the 1570s before passing through a succession of descendants until the late eighteenth century.

The imposing Alcázar de Colón was built to impress, and did so as headquarters of the Spanish court in the New World. The viceroy and his vicereign were considered the most conspicuous nobility at the time, surrounded by an entourage composed of the grandees of the colonial viceregal court and their families. The beautiful Italian Renaissance facades, with their graceful arcades, were sumptuous features typical of the palaces that high officials and wealthy conquistadors commissioned. The prominent house is a copy, on a smaller scale, of a castle in Toledo, Spain. The front, or west, faces the Plaza de Armas and the city, while the east side commands an impressive view of the Ozama River (Fig. 3).

The Columbus family was Italian, and the Italian Renaissance style was popular in Spain at the turn of the sixteenth century, which certainly accounts for the palace’s prominent characteristics. Yet, Mudéjar elements appear throughout the building as well, notably in the door and window frames of the upper floors. Also reflecting minor Moorish influence are the double loggias, with their Renaissance-styled Tuscan columns that support semicircular arches on the lower floor and more elliptically shaped arches on the upper floor.

The Dutch

The first threat to Spanish commercial dominance of the New World came from the Dutch. The three southern Leeward Islands of Curaçao, Bonaire, and Aruba, together with the three northern islands of Saint Marten, Saint Eustatius, and Saba, constitute the Netherlands Antilles. Of the so-called ABC islands (Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao), Curaçao has the greatest landmass and the best examples of architecturally significant buildings in the Netherlands Antilles. The group contains more than one thousand historical sites of interest and more than three hundred sites of extant Dutch colonial plantation houses (landhuizen), though many are in various stages of disrepair. Scattered throughout the countryside, the former plantation estates and houses are more neoclassical in style and make greater use of verandas or galleries and shuttered doors and windows to facilitate airflow and to protect against the unforgiving sun. Among the few that have been faithfully restored is Ascension Landhuis.

Ascension Landhuis

Plantation Ascension was established by Jurriaan Jansz-Exteen in 1672 during Curaçao’s golden age and was one of the largest plantations of the West Indies Company. Built on a sloping knoll where an Amerindian village named Ascension once stood, the house is said to be one of the oldest on Curaçao.

Ascension landhuis is a typical late-seventeenth-century Netherlands Antilles great house, having been built to be defensible (Fig. 4). A hilltop location was selected not only to take advantage of the northeast trade winds but to enable the owner to survey his holdings and to be in plain view of neighboring landhuizen. It was in the owners’ strategic interest to have neighboring estates within eyesight so that they could easily warn one other in case of slave revolts, piracy, or other dangers. The large raised front terrace is surrounded by a retaining wall with two imposing square watchtowers at the front corners. These were used mainly for observation and at times as firing posts for defense. The two sentinel posts have pyramid tiled roofs, or tentdak (tent roof), and were also reputedly used over the years to imprison slaves for punitive measures.

The manor house consists of a long and squat center with a saddle roof. The center core is surrounded on four sides by enclosed galleries used as seating areas (Fig. 5), which are covered by a lessenaar (desk roof). The high-pitched red tile saddle roof has triangular pointed gables on both ends. The geometric triangular gable design predated the eighteenth-century curvilinear gable designs for which the Dutch Caribbean islands are so well known. On both the front and rear of the second-floor saddle roof are four simple dormer windows, or dakkapellen (roof chapels), topped with triangular gables. All the windows and doors have solid wood shutters and are painted with a red and white decorative motif. The lower floor consists of a long central hall that was originally the salon and is used today as both a reception and dining area (Fig. 6). The second floor originally contained a series of bedrooms.

The English

Elsewhere in the Caribbean, it wasn’t until the mid-sixteenth century that Spain’s rival England challenged her dominance, and the Caribbean Sea began to serve as a battleground for the two European powers. England, a Protestant nation, recognized the potential danger of Spain’s Catholic strength not only in the New World but in Europe as well. In an effort to challenge and conquer Spain’s European strongholds and the financial windfalls that her Caribbean treasure fleets were supplying, England consistently attacked the Spanish West Indies and began establishing settlements of her own.

England’s New World colonies included islands throughout the Caribbean chain: Barbados, Trinidad, and Tobago in the south; St. Lucia, Granada, Antigua, Nevis, and St. Kitts farther north; and Jamaica to the west. The earliest settlements of any historical architectural significance on the islands date from the eighteenth century, with the exception of St. Nicholas Abbey and Drax Hall, two of the oldest great houses in Barbados and rare examples of seventeenth-century Jacobean architecture.

St. Nicholas Abbey

St. Nicholas Abbey (the name has no church or religious connection and is reputed to be an affectation) was built by Colonel Benjamin Berringer between 1650 and 1660. What distinguishes St. Nicholas Abbey from all other Caribbean great houses is the facade, with its three elegant ogee-shaped curvilinear gables with tall finials topped with decorative carved stone balls (Fig. 7). The design of these Dutch-style gables was most likely influenced by early Anglo-Dutch shipping and trade. The Jacobean “Dutch” style was also popular in England at the time. There is evidence that, in the

seventeenth century, Dutch traders relied on builders, architects, and engineers from Holland to assist in the construction of Bridgetown, the capital of Barbados.

The British, like so many West Indian islanders today, loved to borrow from the more fashionable Continentals—this Jacobean mansion would have been considered the height of fashion in the 1650s.1 The three rear facade gables are less elaborate, intersected by a single longitudinal gable that has decorative curvilinear gable ends on each side of the house.

The facade has prominent raised plaster quoins around the windows and at each of the building’s four corners. Stone and plaster quoining became increasingly fashionable and was much used in the Caribbean during the eighteenth century. The front entrance is covered with an arcaded Georgian portico that was added in the mid-1700s, probably an attempt to embellish and update the then one-hundred-year-old house. Original lead-lined casement windows were probably replaced at the same time with sash windows, which were the fashionable in the 1750s. They still grace the house.

St. Nicholas Abbey’s rectangular floor plan is divided into four ground-floor rooms with a broad central hall surrounded by four rooms, one in each corner of the building. The interior rooms are relatively simple, with the exception of the moldings, which may be original or part of later embellishments (Figs. 8-9). One outstanding feature is the Chinese Chippendale-styled trellis-like staircase balustrade, another mid-1700s addition (Fig. 10).

The French

- Fig. 16: The north wall of the salon displays many of the main Palladian and neoclassical forms popular in Danish West Indian architecture. Beyond the salon is a reception hall and entrance to the great house. The most distinguished architectural feature of Cane Garden’s salon is its tray ceiling, so called because it resembles an inverted tray.

The great houses (maisons de maître) built by the French represent a particular tropical lifestyle, one of spacious verandas and open-air daytime activities that most often took place in luxuriously large, open gardens. French island architecture was predictably influenced by the styles current in France, particularly those of the Mediterranean coast and from the farms of the country’s northeastern region. One such example of the latter’s climate is the extremely thick masonry walls built to keep interiors cool, a contribution to the design adaptations made for ventilation and shade.

Pécoul

Pécoul Plantation’s great house (maison d’habitation) was built in 1760 and bears the characteristic French West Indian square two-story plan with an enclosed gallery on four sides (Fig. 11). The tiled roof covers the surrounding gallery and the upper floor, or belvedere, the architectural characteristic for which French island great houses are best known. In Pécoul’s case, the windowed belvedere is constructed of wood with walls covered in cedar shingles.

The symmetrical house’s ground floor has a large central room that is currently being used as a dining area. The surrounding gallery has been converted into an office and kitchen on the east and the west, and a reception and salon area occupy the north entrance (Fig. 12). The gallery is the most popular and pleasant location in the house, for it is the coolest and most well-lit interior space. On an island where hospitality is an integral part of life, the gallery functions as the communal gathering spot, and thus is an important social feature.

The surrounding grounds contain the ruins of the old sugar works (Fig. 13), a number of outbuildings that include housing for domestic servants, and stables. According to a notary act of 1764, the adjunct buildings on the north side of the house included a twenty-four-foot-long kitchen, a holding pantry, and a “carpenters” room, which encompassed a stable and a sheepfold. Today the plantation is dedicated to banana cultivation and is one of the largest such enterprises on Martinique.

The Danish

Denmark was the last colonizing European nation to arrive in the Caribbean, settling in St.Thomas in 1672, expanding to St. John in 1683, and finally purchasing St. Croix from the French in 1733. In 1917, the islands were purchased from Denmark by the United States for $25 million and have since been known as the U.S. Virgin Islands. They are often referred to as the “Land of Seven Flags,” a name that refers to the number of nations that have possessed them.

Cane Bay Plantation

The great house at St. Croix’s Cane Bay Plantation was built on St. Croix’s south shore in the last quarter of the eighteenth century and exemplifies the era’s prevailing neoclassical style (Fig. 14). Its situation atop a knoll approximately 120 feet above sea level takes maximum advantage of the cooling trade winds; in addition, it affords a comprehensive view to the north of two hundred terraced acres of the original sugar plantation as well as a panoramic view to the south of the Caribbean Sea. The plantation is located three miles south of Christiansted, the colony’s seat of government and social and cultural center.

In the 1670s, the property became known as Cane Garden. The plantation house is built of locally obtained limestone, yellow brick brought in as ships’ ballast from Denmark, and coral stone extracted from the surrounding reefs, a material favored for its softness and pliability. As is typical of the region’s architecture, exterior and interior walls are finished with a plaster made of sand and lime (fired from crushed coral stone and seashells) mixed with water. Molasses was occasionally used in place of water during the dry season, and to this day some of the walls at Cane Garden and elsewhere in the islands seep molasses. The walls are two and a half feet thick in order to insulate the interior against the tropical heat.

Based on a modified tripartite plan, the arrangement of the rooms is relatively simple and reflects careful planning for comfort in the hot climate (Figs. 15–16). One enters from the north portico into what was originally a small reception room that is now used as a study. It is divided from the larger central drawing room by an architectural screen, whose window-like openings have sliding pocket louvers, a design that offers a degree of privacy while facilitating airflow through the house.

Plantation life in St. Croix reached its peak at the turn of the nineteenth century before slowly declining until midcentury. The decline accelerated due to the discovery of a process to extract sugar from beets as well as the abolition of slavery on the Danish islands in 1848. Happily, the vitality has been returned to the restored Cane Garden great house, which stands today as an important historical reference to the Caribbean’s colonial period while accommodating twenty-first-century living.

Michael Connors Ph.D., has over thirty years of experience in writing, consulting, and teaching the fine and decorative arts. He is particularly known for his studies of the furniture, interiors, and architectural history of the Caribbean islands.

Photography by Andreas Kornfeld, Vanessa Rogers, and Brent Winebrenner.

1. Henry S. Fraser, Treasures of Barbados (London: Macmillan, 1990), 2.