Celebrating the Philadelphia Museum of Art's Costume and Textiles Collection

Celebrating the Philadelphia Museum of Art's Costume and Textiles Collection

by Kristina Haugland

| |

| Fig. 1: Dress with art neediework, American. ca. 1809, Wool twill embroidered with wool and silk in long and short, satin, stem, and straight stitches and French knots; silk twill, lace. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Mrs. Anne S, Finkeldey, Mrs. Guy Alden, and Mrs. Jonn A. Doering; photography by Lynn Rosenthal and Graydon Wood. Crewel wool was used for the leaves and silk for the flowers, as many art needlework or authorities recommended. |

The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Department of Costume and Textiles houses one of the oldest and largest collections of its type in the country. Products of contemporary international manufacturers were first acquired for the collection at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876. By 1893, the museum’s textile collection was formally organized as the Department of Textiles, Lace, and Embroidery.

Enhanced and developed throughout the twentieth century, the Costume and Textiles department now holds significant collections in wide-ranging areas, encompassing some 25,000 objects.1These include Asian and Indian dress and textiles; seventeenth- to nineteenth- century European and American printed textiles; lace; ecclesiastical vestments; historic and contemporary Western fashion; and wide-ranging collections of traditional clothing and textiles, including European folk dress and that of distinctive local communities such as the Quakers and Pennsylvania Germans. The department continues to acquire collection-transforming objects, including those given in honor of the 125th anniversary, which range from Japanese folk textiles to women’s haute couture and cutting-edge menswear of the 1990s. Several displays from this rich and diverse collection are planned for the museum’s celebratory year and beyond.

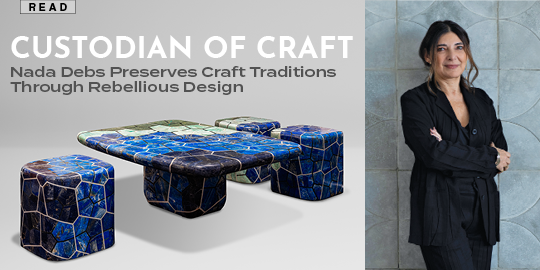

In honor of the museum’s 125th anniversary, the department of Costumes and Textiles was invited to present the loan exhibit In Celebration: Needlework Treasures from the Philadelphia Museum of Art at the Philadelphia Antiques Show from April 7–11, 2001. The exhibition features American and European needlework from the sixteenth through nineteenth centuries. Among the objects on display is an 1880s bustle dress embroidered with art needlework (Fig. 1). In contrast to the popular ornate “fancy work” of the period, art needlework required knowledge of design, encouraged freehand stitching, and employed shading techniques that produced a painterly effect. Enthusiasm for this type of embroidery is credited to a display at the 1876 exposition from the London Royal School of Art Needlework. In response, Philadelphia’s museum-associated School of Industrial Art established the Department of Art Needlework in January 1878.2 The dress in Figure 1, perhaps worked by embroiderers trained at the school, perfectly exemplifies the techniques and aesthetics of this type of art stitchery.

| |

Fig. 2: Nō Robe: Uwagi (outer garment for female role), Karaori-type, Japan, Edo period (1615-1867), ca. 1750-1850. Silk twill weave with silk and gilt thread pattern wefts. Center back length, 51 in. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Henry B Keep; photography by Lynn Rosenthal. |

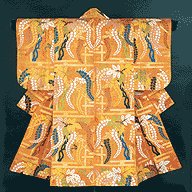

On exhibit in the Costume and Textile Gallery at the museum until May 20, 2001, are costumes used in No, a traditional Japanese theatrical art. Originally derived from court dress, No- costumes diverged from fashionable kimono-type garments to become a distinct variety of sumptuous stage dress in the seventeenth century. This installation features eighteenth- and nineteenth-century examples of several types of No- robes, including robes embellished with floral embroidery and with shimmering stenciled patterns done in gold and silver leaf. Karaori robes (Fig. 2) are generally worn as outer garments for female roles; the color red indicates this example was used to portray a young woman. The stiff and heavy silk gives a regal effect, appropriate for aristocratic No- drama; the wisteria and lattice motifs are intricately woven with floating wefts that give the impression of embroidery.

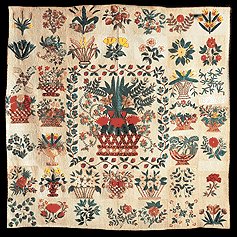

After May 26, 2001, the Costume and Textiles Gallery will feature nineteenth-century needlework. This installation will display samplers and quilts from the collection, including an embroidered crazy quilt from the 1870s and the album quilt pictured in Figure 3. The museum’s significant quilt collection includes particularly strong holdings of friendship, or album, quilts, which became very popular in the 1840s. The album quilts made in Baltimore, Maryland, are composed of blocks that suggest pages from pictorial, remembrance, or autograph albums, reflecting Victorian sentimentality. The masterful appliqué of this Baltimore album quilt makes excellent use of printed fabrics, while padding gives the bold motifs dimension.

|  | |

| Fig. 3, left: Album quilt made by Cynthia Ashworth, Baltimore, Maryland, ca. 1840-1845. Cottor plain weave with block- and roller-printed chintz appliqué; silk embroidery in chain stitch; channel quilting, 93 x 93 in. Courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art; gift of Mr. and Mrs. Percival Armitage; photography by Graydon Wood. Fig. 4, right: Dresden work sampler embroidered by Jane Humphreys, (b. 1759), Philadelphia, 1771. Plain weave linen embroidered wth linen in drawn fabric and drawn threadwork, cutwork. needle-lace darning (filet), hollie point, button-hole, satin, and chain stitches. 13-1/4 x16 in. Courtesy of Philadelphnia Museum of Art: gift of Miss Lettie Humphreys: photography by Lynn Rosenthal. | ||

Needlework samplers, an important educational tool and social accomplishment for girls, are well represented in the museum’s collection. The nearly 700 needlework samplers and embroidered pictures include the extensive Whitman Sampler Collection, given by the well known Philadelphia candy makers in 1969. In addition to the samplers displayed at the antiques show and in the Costume and Textiles Gallery, a selection of Delaware Valley examples will be on view in the museum’s American Wing through the summer of 2001. This installation will include the sampler in Figure 4, worked by Jane Humphreys in 1771 when she was only 12 years old. This sampler belongs to a group of whitework samplers made in the second half of the eighteenth century that are unique to Philadelphia, reflecting the influence of earlier European samplers, but without foreign or American counterparts.

| |

Fig. 5: Evening coat designed by Elsa Schiaparelli (Italian, active France. 1890-1973). 1938-39, Patchworked fulled wool with silk and cotton couched chain stitches. Center back length, 57-1/2 in. Courtesy of the Philadelonia Museum of Art: gift of Mme. Elsa Schiapareli; photography by Lynn Rosenthal and Graydon Wood. |

These floral patterned samplers were made with drawn fabric stitches, in which the threads of the background fabric were pulled aside by tightly worked embroidery stitches, forming a pattern of holes. A cheaper and more durable alternative to lace, this type of needlework was popular in mid-eighteenth-century northern Germany and was therefore called “Dresden work” in England and the American Colonies. A variety of other needlework techniques are employed in this sampler. For example, filet or lacis work, in which a netlike grid of threads is darned with a pattern, is used in the basket, border, and panel with Humphreys’s name, while cutwork is used for the decorative circles, with the ground fabric cut away and replaced by needle lace insertions.

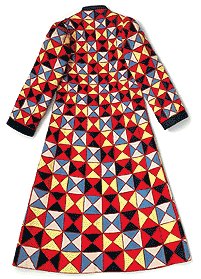

While the museum had acquired examples of historic and contemporary dress over the years, the costume and accessory collection came into prominence after 1947. From that year to the early 1980s, the Fashion Wing showed dress and accessories from the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries—including Princess Grace’s wedding gown. In recent years, special exhibitions have highlighted this collection. Currently, curator Dilys Blum is preparing another major exhibition tentatively scheduled for 2003 that will focus on the work of Italian-born fashion designer Elsa Schiaparelli, fashion’s greatest innovator in Paris before the Second World War.

Schiaparelli, who collaborated with Salvador Dali, Jean Cocteau, and other avant-garde artists, treated garments as an experimental art form, utilizing the subversive goals of surrealism to imbue sophisticated high fashion with playfulness and irreverence. In 1969, the designer donated over seventy garments and accessories to the museum, including the Harlequin evening coat from her Commedia dell’arte collection, shown in Figure 5, in which colorful woolen triangles form squares that are cleverly shaped for the torso and gradually increase in size from neck to hem.

Philadelphia Museum of Art Costume and Textiles Publications:

Blum, Dilys. The Fine Art of Textiles: The Collections of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1997.

Blum, Dilys and Kristina Haugland. Best Dressed: Fashion from the Birth of Couture to Today, 1997.

Blum, Dilys. Ahead of Fashion: Hats of the 20th Century, 1993.

Blum, Dilys and Jack L. Lindsey. Nineteenth Century Appliqué Quilts, 1989.

Handbook of the Collections, 1995.

|

1. Costume and Textiles is one of the departments slated to move into the art deco Perelman Building, recently purchased by the museum and currently undergoing renovation. In addition to increased storage and study space, the new building will provide larger galleries allowing for increased exhibition of the costume and textile collection.

2. The school operated independently as the Philadelphia School of Art Needlework until its close at the beginning of the First World War.

|

Kristina Haugland , Assistant Curator of Costume and Textiles at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, earned an M.A. in the History of Dress from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. She enjoys writing and lecturing, especially on her special interests, underwear and etiquette.