Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature

|

Fig. 1: Claude Monet (1840–1926), The Artist’s House at Argenteuil, 1873. Oil on canvas, 23-11⁄16 x 28⅞ inches. The Art Institute of Chicago: Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection (1933.1153). Photograph courtesy The Art Institute of Chicago under CC0 Public Domain Designation. |

| |

Fig. 2: Claude Monet (1840–1926), Rocks at Belle-Île, Port Domois, 1886. Oil on canvas, 31⅞ x 25⅝ inches. Cincinnati Art Museum, Ohio: Fanny Bryce Lehmer Endowment & The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial (1985.282)/Bridgeman Images. |

Claude Monet—arguably the most influential of the French Impressionists—is the focus of the most comprehensive exhibition of his work in the United States in more than twenty years. Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature, co-organized by the Denver Art Museum and the Museum Barberini (Potsdam, Germany), runs through February 2, 2020 in Denver and opens in Potsdam (as Claude Monet: Orte) on February 22, 2020.

The exhibition explores Monet’s enduring relationship with nature and his response to its varied and distinct manifestations in the places where he worked. Monet’s constant quest for new motifs shows the artist’s appreciation for nature’s ever-changing and mutable character, not only from place to place but from moment to moment, a concept that eventually became a central focus of his art when he embarked on his famous series paintings. Monet’s rapport with nature was not one of passive reverence, of absorbing the motif as it presented itself. Monet was intentional in his choices and strategic in his travels, at times forming in his mind the ideal and desired composition and then looking for it in nature, as he explains in letters to his dealer Paul Durand-Ruel and his second wife, Alice Hoschedé. On January 23, 1884, he writes to his dealer from Bordighera, Italy, to share his plans: “I intend to do a sojourn of three weeks around here, so I can bring back some varied things. Here I will focus on palm trees and aspects that are a little bit exotic. Elsewhere I will paint water, a beautiful blue water.” 1 Even upon his arrival, Monet had a clear vision of the compositions and color palettes he intended to explore.

|

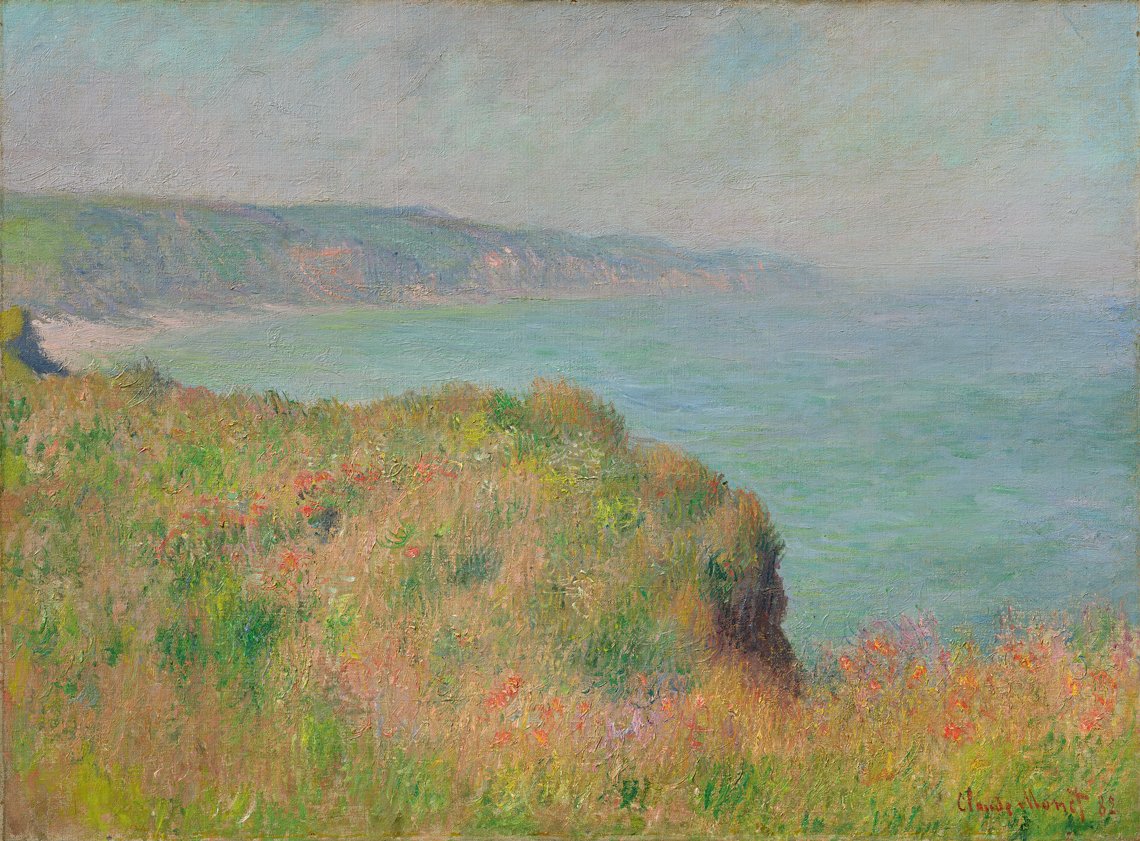

Fig. 3: Claude Monet (1840–1926), Edge of the Cliff at Pourville, 1882. Oil on canvas, 23¾ x 32 inches. Private collection. |

He sought to capture the spirit of a certain place and then translate this to canvas. This pursuit led him to locales as varied as serene Argenteuil (Fig. 1) and rugged Belle-Île (Fig. 2), windy Pourville (Fig. 3) and the sunny Mediterranean (Fig. 4), to name a few. Monet was committed to change and believed it to be essential to the artist’s practice; to Durand-Ruel he admits on October 28, 1886, that “although I am the man of the sun, as you say, one should not specialize in a single note.” 2 And in a letter to Alice, written on the same day, he is even more candid: “This evening I have received some money from Durand, and, like you, he seems decidedly uneasy to see me paint such a sad place; and now, after having talked about going to America, he advises me to come back and spend the winter in the South, because, he says, my business is the sun. Well! We will end up boring me with the sun! We must do everything, and that is why I am happy to do what I do.” 3 More than any other impressionist, Monet explored the different moods of nature, unafraid of abandoning the light color palette associated with the Impressionist movement and tailoring his chromatic choices to his emotional response.

This exhibition shows the changing quality of nature: its light, colors, and natural elements. Monet understood that it is not just the place itself, but rather the unique and distinctive light and atmospheric conditions of such a place—what in French he called the “enveloppe”—that revealed the specific character of a site.

|

Fig. 4: Claude Monet (1840–1926), View of Bordighera, 1884. Oil on canvas, 26 x 32-3⁄16 inches. The Armand Hammer Collection: Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation. Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. |

|

Fig. 5: Claude Monet (1840–1926), La Pointe de la Hève at Low Tide, 1865. Oil on canvas, 35½ x 59¼ inches. Courtesy Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Tex. (AP 1968.07). |

| |

Fig. 6: Claude Monet (1840–1926), Boulevard des Capucines, 1873-1874. Oil on canvas, 31⅝ x 23¾ inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: the Kenneth A. and Helen F. Spencer Foundation Acquisition Fund (F72-35). Photo courtesy Nelson-Atkins Media Services / Jamison Miller. |

By focusing more and more on fewer sites, where he could study the changes of light during an extended period, he allowed himself to truly comprehend the spirit of a place. He wrote about this from Bordighera on March 25, 1884: “You have to live in a place for a while to paint it, you have to have worked hard to render it accurately.” 4 A few years later, from Belle-Île, he wrote on October 30, 1886, that “to really paint the sea, you have to see it every day, at every hour in the same spot to understand its ways in that place.” 5

The exhibition’s sections reflect Monet’s desire to seek both familiar and unfamiliar locales. After his youth in Normandy, where he grew up surrounded by lush countryside and the examples of artists like Eugène Boudin and Johan Barthold Jongkind (Fig. 5), Monet moved to Paris, whose bustling boulevards (Fig. 6) and manicured public parks offered plenty of painting opportunities for young artists who sought to engage with the newly urban and modern world around them. Later sections address his years in Argenteuil, a fashionable escape for city dwellers only fifteen minutes by train from Paris, where he resided from 1871 to 1878; and Vétheuil, a rural village whose natural surroundings inspired Monet toward pure landscapes devoid of human presence. Trips to the dramatic cliffs of the Normandy coast and the “sinister” rocks of the island of Belle-Île, off the cost of Brittany, alternated with sojourns in the South of France, in particular, Bordighera and Antibes on the Riviera. Here, the enchanting light and exotic vegetation of the Mediterranean was unlike anything he had experienced before, and he produced a number of landscape paintings for which he felt he needed jewel-like colors to render accurately the buildings, palm trees, and azure water: “I’ve caught this magical landscape and it’s the enchantment of it that I’m so keen to render. Of course lots of people will protest that it’s quite unreal and that I’m out of my mind, but that’s just too bad.” 6

|

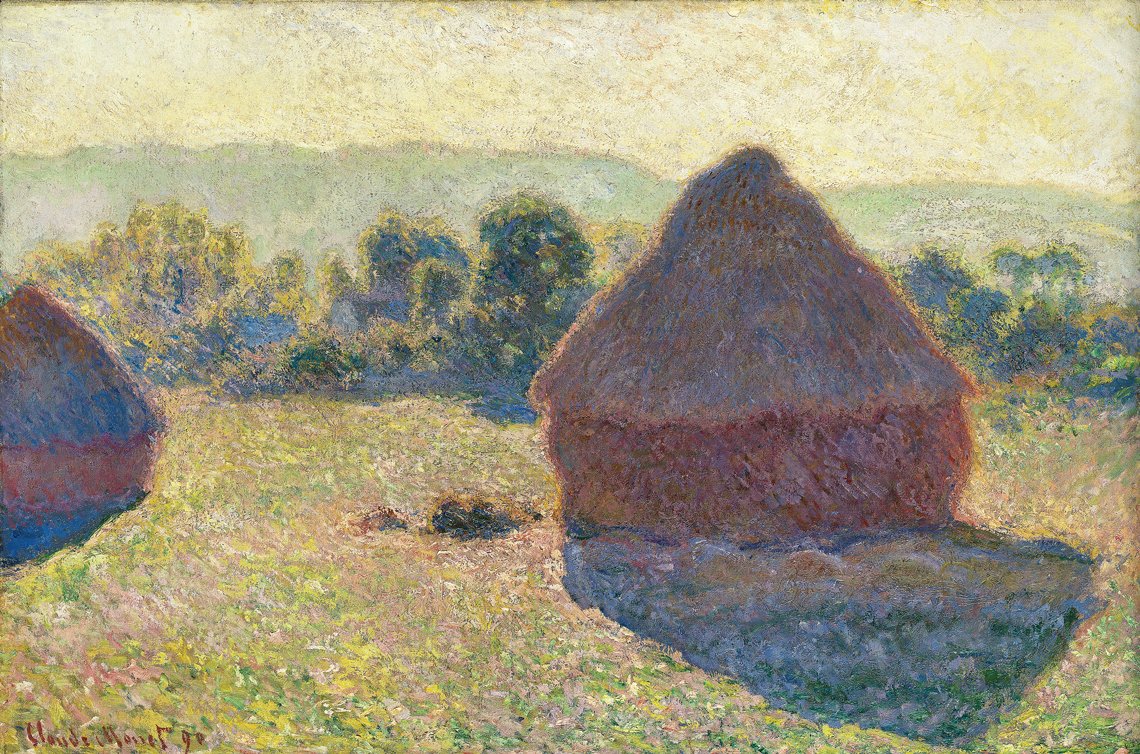

Fig. 7: Claude Monet (1840–1926), Haystacks, Midday, 1890. Oil on canvas, 25⅝ x 39⅜ inches. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra: Purchased 1979 (NGA 79.16). |

|

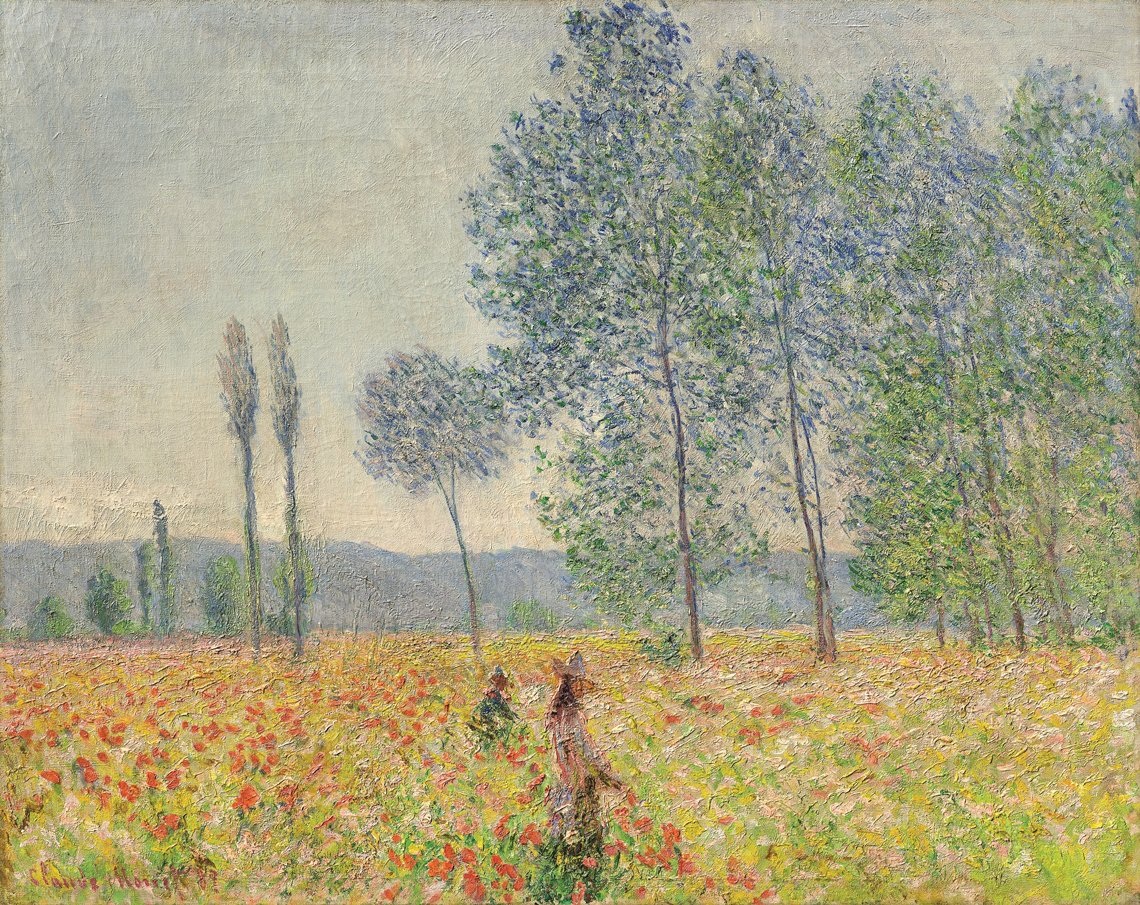

Fig. 8: Claude Monet (1840–1926), Under the Poplars, 1887. Oil on canvas, 28¾ x 36¼ inches. Private collection. |

During the later part of his life, Monet began to focus on painting series of the same subject, and the exhibition offers examples of his grainstacks (Fig. 7), poplars (Fig. 8), Waterloo Bridge, and mornings on the Seine, culminating with a gallery dedicated to his water lilies. It was in Giverny, where he had rented a home since 1883, purchasing it and settling in permanently in 1890, that he began creating his magnificent garden, a masterpiece of color and exotic plants that offered an endless source of motifs, in particular, the reflective world of his water lily pond. Works in this section range from early examples (Fig. 9), which still reference the physical structure of the Japanese-style bridge, to late canvases where the same bridge seems to dissolve into the surroundings, rendered with radical, free brushstrokes that anticipate the abstract tendencies of mid-twentieth-century painting (Fig. 10).

Monet loved to immerse himself in nature, preferably in solitude, but his rapport was not dictated by the romantic notion of nature’s superiority over man. Despite his occasional lamenting of the overwhelming beauty of the landscapes before him, Monet sought to control his environment, both in nature and on the canvas. This tendency to direct his life was apparent in anything concerning his business matters, the time he ate every day, and his carefully planned garden in Giverny. Even Alice Hoschedé admitted matter-of-factly to her daughter Germaine Salerou on October 27, 1904, that “Monet, who leaves nothing to chance, asks me to tell you to start dining if we are not here by 7:30.” 7 Indeed Monet left nothing to chance, and to him nature could be disappointing, not so much in its unpredictable manifestations—although his letters contain numerous complaints of unfavorable weather—but in not providing at times the “right” motif, the one he was seeking. Again, Alice to her daughter on January 1, 1909: “Poor Monet is so sorry not to be able to paint outside, but it would not be wise; indeed from the windows here the effect is not as he wishes it to be.” 8

|

Fig. 9: Claude Monet (1840–1926), Waterlilies and Japanese Bridge, 1899. Oil on canvas, 35⅝ x 35-5⁄16 inches. Princeton University Art Museum: From the Collection of William Church Osborn, Class of 1883, trustee of Princeton University (1914-1951), president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1941-1947); given by his family (y1972-15). Photo courtesy Princeton University Art Museum/Art Resource, NY. |

|

Fig. 10: Claude Monet (1840–1926), The Japanese Bridge, 1918–1924. Oil on canvas, 35 x 39⅜ inches. Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris/Bridgeman Images. |

This sense of nature’s inability at times to measure up to his expectations, so often encountered in his letters, is evidence of a punctilious mind, that of a person who made methodical, highly intentional, and purposeful artistic choices. This is apparent not only in the context of his series practice, but also in the planned and systematic approach to compositions Monet displayed throughout his life. Monet did not stumble across inspiring places; he sought them, he chose them, and he painted them, at times over and over again. He spent his entire life chasing the truth of nature.

1. Letter from Claude Monet to Paul Durand-Ruel, January 23, 1884, in Wildenstein, Daniel. Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 2: 1882–1886, Peintures. Lausanne and Paris, 1979, 233, no. 391.

2. Monet to Durand-Ruel, October 28, 1886, in Claude Monet, 285, no. 727.

3. Monet to Durand-Ruel, October 28, 1886, in Claude Monet, 284, no. 726.

4. Monet to [unknown], March 25, 1884, in Claude Monet, 246, no. 460.

5. Monet to Alice Hoschedé, October 30 [1886], in Claude Monet, 285, no. 730.

6. Monet to Alice Hoschedé, March 10, 1884, translation by Bridget Strevens Romer, in Richard Kendall, ed., Monet by Himself: Paintings, Drawings, Pastels, Letters (New York, NY: Chartwell Books, 2014), 111.

7. Alice Hoschedé to Germaine Salerou, October 27, 1904, in Jacqueline and Maurice Guillaud, Claude Monet at the Time of Giverny (Paris: Centre Culturel du Marais, 1983), 269.

8. Hoschedé to Germaine Salerou, January 1, 1909, in ibid., 278.

|

The exhibition Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature, is on view at the Denver Art Museum through February 2, 2020. The DAM is the only U.S. venue for this presentation. The exhibition then travels to the Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany, opening on February 22, 2020. For information, visit denverartmuseum.org or call 720.913.0130.

Angelica Daneo is chief curator and curator of European art before 1900 at the Denver Art Museum.

Unless otherwise noted, translations are by the author.