Crafting Modernism: The Dawn of the Studio Craft Movement

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2011 issue of Antiques and Fine Art; AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

Hand-made objects, long subservient to an artificial hierarchy of the arts established in the Renaissance, underwent a paradigm shift in the postwar period, defined here as 1945 to 1969, and became an assertive form of artistic expression. Craftspeople found affirmation in the creations of Alexander Calder and Isamu Noguchi, who roamed freely across media and disciplines without regard for superficial divisions. The changed status of craft was not widely accepted by the fine arts world, but the altered relationship was nevertheless made plain by those who appropriated craft-based materials and techniques into aspects of postwar art, and by craftspeople whose work addressed such fine-arts concerns as process, form, and content (Fig. 1).

Today the studio craft movement is a vital aspect of the world art scene, supported by in-numerable galleries, periodicals, conferences, fairs, and collectors —a far cry from the movement’s scattered, isolated origins in the postwar era. Its emergence is indebted to the artists who took their materials and techniques to explore new frontiers, the entrepreneurs who opened the first galleries, and the individuals who collectively worked, discussed, educated, and organized their field into a regional, national, and ultimately international presence.

Several factors contributed to these developments. Chief among the catalysts was Aileen Osborn Webb, a philanthropist of great vision and energy. Webb was responsible for conceiving and setting in motion a range of the organizational “firsts” that supported craftspeople and promoted the crafted object. As early as 1940, she opened America House, the first gallery to showcase contemporary handcrafted work made in this country, and founded the American Craft Council to serve artists working in craft media.

She also created Craft Horizons magazine (today’s American Craft) as a means of sharing new work, and founded the Museum for Contemporary Crafts (today’s Museum of Arts and Design), the first museum in the United States to feature craft media by living artists. Webb’s last great contribution was the World Craftsman’s Council, an idealistic organization formed in 1964 to provide support for indigenous craftspeople around the world. In less than twenty-five years of sustained effort, Webb’s many-faceted enterprises spawned countless related activities, as well as regional and media-based organizations—the Society for North American Goldsmiths being just one example.

Webb’s School for American Craftsmen, originally founded to educate returning veterans, was among the many schools of higher education fueled by the GI Bill. As craft-based programs shifted from factory and apprentice-based origins into the academic realm, students encountered contemporary artistic trends and theories and blended these concepts into the technical aspects of their work.

Greater numbers of students meant an increase in educators. Many were recent émigrés from Europe, such as ceramists Frans and Marguerite Wildenhain and the painter Josef Albers and his wife, weaver Anni Albers (Fig. 2). They brought a modernist perspective shaped by the Bauhaus, the avant-garde German school whose objective was to unify art, craft, and industry. Other foreign-born teachers came with traditional training, among them School for American Craftsmen professors John Prip and Tage Frid of Denmark, highly skilled journeymen in their respective areas of metalsmithing and woodworking.

The GI Bill had further advantages as white-collar work became a reality for many graduates who were often the first in their family to receive a college education. Education brought middle-class life within reach for many Americans. Along with it came home ownership, spurring suburban development and the commensurate furnishings they required, both manufactured and handmade. The end of the war and homecoming servicemen meant the end of wartime fears and privations, and the resumption of normal life. Peace brought a newfound freedom of spirit that sometimes crystallized in a countercultural critique of the establishment. There was a new search for purpose in a world that was increasingly dominated by the machinations of business and government. Some resisted the need to conform, whether as consumers “keeping up with the Jonses,” or in the behavior and dress expected of corporate employees.

The craftsman lifestyle was attractive to many who were concerned with these societal issues. Some chose self-employment, seeing small scale production work as a means to a self-sufficient life. Others chose teaching careers as schools continued to swell in size throughout the 1960s. Another option was to team with industry, where the term craftsman-designer was coined to describe artists who created objects with mass-production capabilities. In most cases, their choice was less a romanticized rejection of industrial society than a determination to direct their own lives. “Many…saw this [the life of a craftsman] as a simple, humbler approach to finding a life which had meaning,” recalled the ceramist Robert Turner.

Industrial design had emerged as a separate profession earlier in the century, and in the 1950s many designers employed a reductive and spare approach to furnishings that matched the international style then popular in architecture. This prompted some designers to develop products to counteract the severity of modern architecture. Ceramics and textiles yielded particularly effective results with this approach, as seen in Russel Wright's thickly glazed Bauer ceramics (Fig. 3) and Jack Lenor Larsen’s textiles that softened the geometry of corporate interiors. In furniture, Ray Eames borrowed from the sculptural aspects of African furniture to create her lively stool for the lobby of the Time-Life Building, and Ed Wormley incorporated ceramics by Otto and Gertrud Natzler into the dressers and tables he designed for Dunbar (Fig. 4).

This was not a strictly American phenomenon. Craft Horizons featured the work of folk craftspeople and internationally ranked artists from abroad, and reviewed exhibitions at MoMA of Japanese ceramics by Rosanjin and liturgical vestments by Matisse, while foreign magazines such as Domus, Abitare, and Graphis brought the latest thinking on European architecture and design to American doorsteps.

The widespread influence of Scandinavian design had begun in the 1920s when the Danish silversmithing firm Georg Jensen opened its first New York showroom. By midcentury, New York galleries were devoted to the genre. Two major exhibitions of the era included Design in Scandinavia, which circulated in 1954 to twenty-two museums in the United States, and The Arts of Denmark: Viking to Modern, seen at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1960. Craftsmen like Hans Christensen (Fig. 5) and John Prip from Denmark, and Marianne Strengell from Finland, became teachers in American schools, where they were responsible for injecting a Nordic aesthetic into postwar design. The Long Island–based firm, Dansk, traded on the American attraction to the organic forms and truth-to-materials characteristics of Nordic design with a successful line of household products that was entirely Danish in origin.

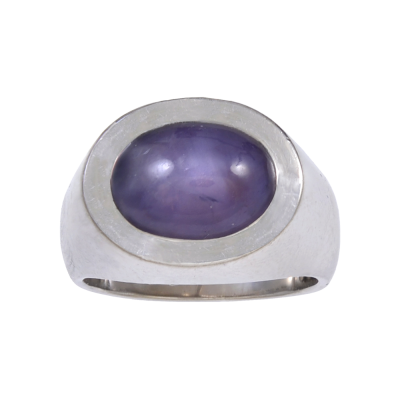

At home, Native American artists began to make their own unique contributions to the field. Alaskan Inupiat Ron Senungetuk and Hopi artists Charles and Otellie Loloma (Fig. 6) attended the School for American Craftsmen, blending their cultural perspectives with a modernist sensibility. Lloyd Kiva New, of Cherokee and Scots-Irish heritage and a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, moved from textile design to early leadership in the Southwestern crafts movement. New established the Institute for American Indian Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico, to enable young Native artists to create contemporary art based upon their tribal roots.

In the two decades following World War II, Abstract Expressionism, Surrealism, and Pop Art were particularly attractive art movements for craft artists who explored the purely formal properties of art production. Abstract Expressionist approaches to painting were adapted to ceramics by the Los Angeles-based Peter Voulkos, who was the first ceramist to cut ties with functionalism by making vessels of unprecedented scale and vitality (Fig. 7). The seeds of his improvisational method were sown during a 1953 visit to the East Coast. Voulkos first visited Black Mountain College, where he briefly taught that summer, and later traveled to New York City, where he encountered potter and poet M. C. Richards, painters Robert Rauschenberg and Franz Kline, dancer Merce Cunningham, and composer John Cage, among others. All were conversant with the notion of gestalt therapy that encouraged action and process-based behavior, revealing the interaction between the artist and his medium. These concepts soon appeared in Voulkos’s work and that of many who followed in his wake.

This was a two-way street. Just as Voulkos drew from Abstract Expressionism, craft media was appropriated by fine-arts practitioners. Lucas Samaras, Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, and Robert Rauschenberg, among others, unreservedly wove ceramic, fiber, and wood, found objects, and other materials into their work. In so doing, they upended time-honored conventions of painting and sculpture and opened the door to further experimentation. They also followed in the foot-steps of Alexander Calder and Isamu Noguchi, who continuously worked across the functional / nonfunctional divide, blurring concepts of art, craft, and design. These rich examples of artistic cross-fertilization are a special part of MAD’s exhibition.

As the Civil Rights movement, the Vietnam War, and Women’s Liberation of the 1960s introduced sweeping and often turbulent social changes to American society, artists responded in a variety of ways. Some expressed their anger and frustration through social commentary (Fig. 8). Others led artistic revolutions that separated them from early leaders of the studio craft movement. Robert Arneson, for instance, led the “California Funk” group away from the predominance of sober, stoneware vessels and dark glazes to experiment with brightly colored low-fire whiteware that often related personal narratives in a figurative style. Still others chose a crafts-based lifestyle as a means of rebellion against the homogeneity and mass-production prevalent in American society (Fig. 9). Many turned to the Whole Earth Catalog, Stewart Brand’s manual for independent living, for guidance in making virtually anything. With the advent of the late-sixties psychedelic culture, artists also turned to fashioning such countercultural icons as pipes for smoking banned substances and otherwise adorning themselves and the objects around them with the melting, curvilinear designs characteristic of poster art from the period.

These creations entered the public realm through museum exhibitions and publications, and added to the ongoing dialogue on meaning in American art and life that was shared with poetry, literature, dance, music, and theater.