En Plein Air: Painting and Photography in the Forest of Fontainebleau

This article was originally published in the Spring 2008 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

Although the history of modern French landscape art is often thought to have begun with impressionism in the 1860s, a new exhibition at the National Gallery of Art argues that its true origins go back even farther. In the Forest of Fontainebleau: Painters and Photographers from Corot to Monet explores through paintings, pastels, photographs, artists’ equipment, and tourist ephemera an evolution that originated in the plein air practice by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and his contemporaries in the 1820s and ‘30s and progressed to what is now its most familiar manifestation, impressionism.

Once the domain and hunting grounds of kings and emperors, the Forest of Fontainebleau, some thirty-five miles southeast of Paris, was the center of this new approach to landscape. Its close proximity to Paris made it a convenient and accessible retreat, while its variegated topography, which combined magnificent old-growth trees, stark plateaus, and dramatic stone quarries, offered a wealth of landscape motifs. In the 1820s and 1830s painters such as Corot and Théodore Rousseau traveled to the forest and helped to transform the villages of Chailly and Barbizon into informal artists’ colonies and the forest into an open-air studio. Through their close observation of the native countryside, they sparked the Barbizon School movement that introduced a new sense of naturalism into landscape painting and challenged longstanding landscape conventions.

Soon after the invention of photography in 1839, photographers such as Gustave Le Gray and Eugène Cuvelier began to travel to Fontainebleau, likewise seeking to capture the ephemeral moods of nature. Often working side by side, photographers and painters inspired each other to explore new ways of representing landscape. In the 1860s, a new generation that included Claude Monet and Alfred Sisley discovered Fontainebleau anew, laying foundations for the light-filled depictions of the outdoors that brought them fame as impressionists.

One of the first artists to travel to the Forest of Fontainebleau in the 1820s, Enfantin here celebrates not only the extraordinary topography of the forest but the camaraderie of this nascent artists’ colony that was an integral part of Fontainebleau’s allure. A pair of artists is depicted within a wild and chaotic landscape, their figures dwarfed by the tumult of rocks and lush greenery. One is perched atop a massive boulder while his companion sits on a camp stool and diligently paints the scene before him, his paint box and parasol close at hand.

Corot was among the first artists to discover the Forest of Fontainebleau. He first traveled there in 1822, when he produced some of his earliest open air studies, and returned in 1829 after an extended sojourn in Italy. Painted shortly after his return, this painting reflects Corot’s dedication to the forest and his mastery of plein-air techniques honed during his time abroad. Renowned for its gnarled, twisted limbs and its seeming indestructibility in the face of the ravages of nature, this oak tree, nicknamed Le Rageur, or the Raging One, was a favorite motif of artists. But it is the luminosity of Corot’s palette and the deft, uncomplicated brushwork that speaks of the new approach to painting that was beginning to take root in Fontainebleau.

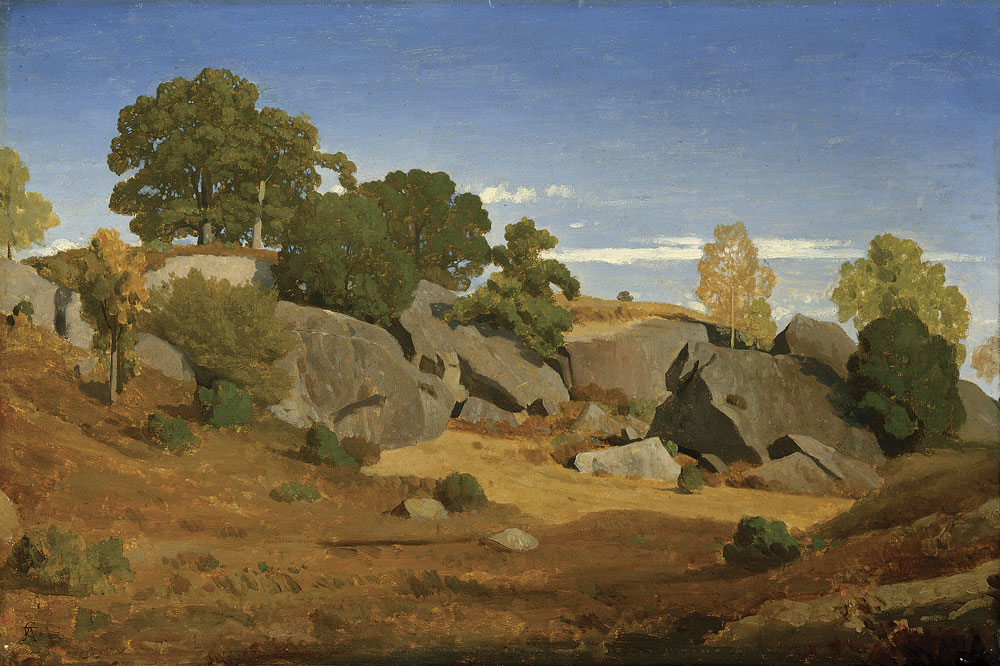

Caruelle d’Aligny encountered Corot during his sojourn in Italy in the mid-1820s and like Corot, he gravitated to the Forest of Fontainebleau soon after his return to France to continue the experiments in plein-air painting. Like many of his contemporaries, Caruelle d’Aligny found in Fontainebleau a surrogate for Italy. He was especially drawn to the region of Gorges aux Loups, an area famous for its rough hewn terrain that was startlingly reminiscent of the countryside around Rome. With its crisp, vibrant light and the sharply delineated planes of the tumbled mass of boulders, a viewer could easily imagine himself in the sun-drenched plains of Italy rather than a forest, hours from Paris.

Early photographic methods presented unique challenges for landscape photography. Heavy equipment and dangerous chemicals made travel difficult, while early photographic chemicals, insensitive to greens, required long exposure times. The introduction of the paper negative process in 1847 revolutionized landscape photography. Gustave Le Gray, perhaps the first photographer to work in the Forest of Fontainebleau, used these advances to great effect. Here he depicts the Pavé de Chailly, the primary route between Paris and Fontainebleau, deftly juxtaposing the open expanse of the road with the magnificent oak trees that flanked it. The remarkable play of light across the tree trunks and the registration of crisp detail in the foliage make this work a technical and artistic tour de force.

This is a relatively rare pure landscape by Bonheur, an artist better known for her depictions of animals. Bonheur was well acquainted with the forest, however, having visited Barbizon in 1853, before eventually settling in the Château de By in Thoméry, a village on the eastern edge of the forest. Painted shortly after her arrival in Thoméry in 1859, Bonheur’s work eschews the more dramatic aspects of the forest in favor of a calm, idyllic depiction of springtime in the forest, redolent with fresh air, sunshine, and lush, young foliage. It is an inviting image, promising respite from the noise and crowds of nearby Paris. Her Fontainebleau is a longed for refuge that paradoxically was rapidly vanishing under the deluge of Sunday tourists.

Rousseau is the artist most associated with the Barbizon School movement. Named for the village that was home to the thriving artists’ colony, its members rejected established conventions of composition and surface finish in favor of rigorous observation and sincerity, with the Forest of Fontainebleau serving as both open-air studio and principle laboratory for their endeavors. Rousseau was preoccupied with the subtle shifts of season and weather, returning repeatedly to the same motifs in order to record their effect upon nature. This painting is a striking example of his dedicated pursuit of the ephemeral. It depicts a site in the Gorges d’Apremont renowned for its rugged terrain and sparse vegetation, but its true subject is the extraordinary light, as the setting sun bathes the scene in a vibrant, ruddy glow. With its dramatic palette and thinly painted surface that recalls drawing as much as painting, it exemplifies the frequently experimental nature of Rousseau’s work that made him one of the most innovative landscape artists of his time.

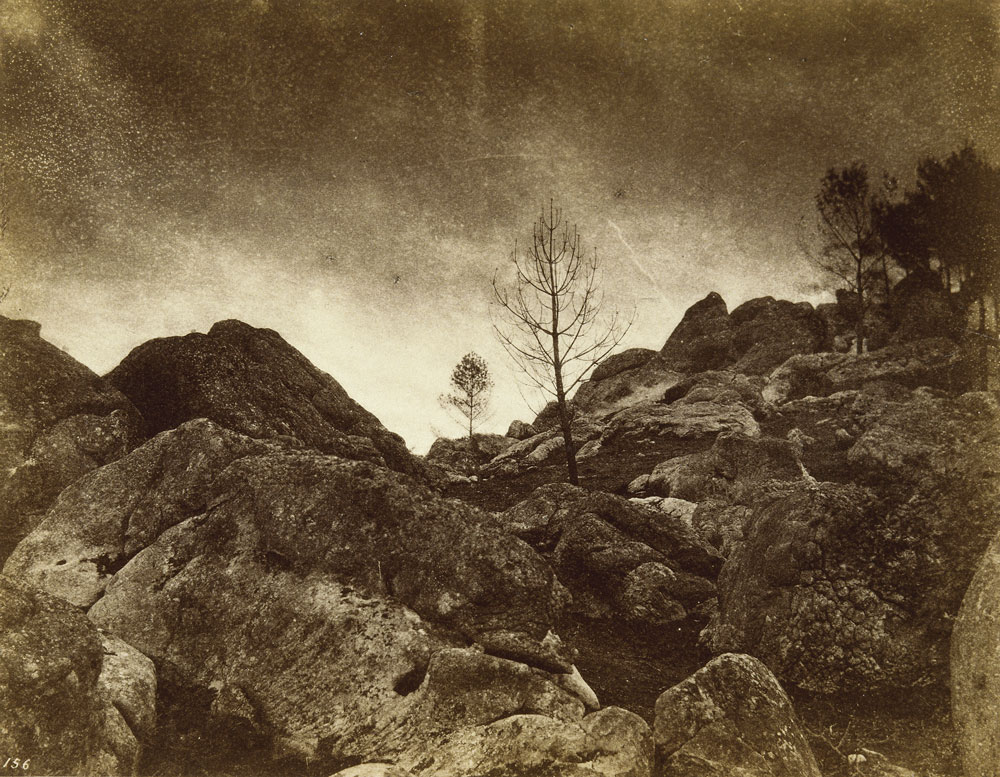

Like Le Gray, Cuvelier was another photographer who studied landscape painting as a young man, training that eventually led him to Fontainebleau on multiple occasions. In 1859, he took up residence in the village of Barbizon after he married Louise Ganne, the daughter of the innkeeper whose Auberge Ganne had become a famous gathering point for artists. Over the next decade, he photographed the forest in all seasons, venturing far beyond the popular tourist circuits. Although his photographs were made primarily for his own pleasure and the admiration of his fellow artists, Cuvelier revealed himself to be the most faithful chronicler of the forest and its myriad moods. Set in one of the most savage regions of the forest, possibly Franchard, The Storm, Fontainebleau is as much an evocation of place as it is a study of the mutability of nature itself. The contrast between the intransience of the rocky terrain and the ephemerality of the storm passing overhead lends the work a power few others could match.

This is the largest and most elaborate of Courbet’s pure landscapes. As its monumental scale suggests, it is a studio piece painted far from the forest that inspired it. Although Courbet knew Fontainebleau, this painting is as much a product of the artist’s imagination as any observed reality. Incorporating elements of the forest such as the rocky terrain and powerful oak trees, Courbet introduced the more fanciful elements of the pool of freestanding water, so out of place in the barren gorges of the forest, and the chain of blue-tinged mountains glimpsed in the distance. It is a fantasy image, one that merges memories of Fontainebleau with those of the artist’s native Franche-Comté region. For all its imaginative rendering, Courbet’s use of the palette knife, his broad, deft handling of the paint surface, and predilection for dramatic compositions captures the raw, savage aspects of the Forest of Fontainebleau more skillfully than many more faithful renderings.

Famin is one of the many photographers who made the pilgrimage to the Forest of Fontainebleau, traveling there at least twice. In contrast to many of his contemporaries who specialized in either landscape or figural subjects, Famin’s photographs of Fontainebleau show exceptional range, exploring animal studies, scenes of rural life and, of course, depictions of the forest itself with equal ease. Here Famin captured the grandeur and the pristine beauty of the Forest of Fontainebleau as a solitary figure wanders among towering trees rising skyward like the columns of a cathedral. It is a quiet, contemplative image, but also a misleading one. When Famin produced this photograph, the Forest of Fontainebleau had ceased to be the exclusive refuge of artists it had once been. The establishment of a railway line in 1849 had transformed Fontainebleau into a popular tourist destination for Parisian day-trippers in search of an escape from the confines of the city. The solitude evoked in this work was largely a thing of the past.

In the spring of 1865, Monet undertook an extended sojourn to Fontainebleau to begin work on his monumental canvas Déjeuner sur l’herbe. Over the course of several months he produced numerous paintings and drawings, including this one, in the forest near the village of Chailly, where he’d taken up residence. The subject is a tree named for the Swiss painter Karl Bodmer who had taken it as the subject of a number of paintings and prints beginning in 1850. Dramatic and distinctive, this knotty oak tree became the signature motif that helped cinch Bodmer’s reputation even as it attracted other artists for years thereafter. Monet’s depiction of this celebrated tree is undeniably the most famous of them all, eclipsing even those of Bodmer himself. Although its palette is unexpectedly dark, composed of deep jewel tones well suited to the depths of the forest, Monet’s brushwork displays the vigor and fluency that would become the hallmark of impressionism.

In June 1849, Millet moved his family to the village of Barbizon to escape a cholera epidemic in Paris. He would remain there until his death in 1875. For Millet, who was drawn to scenes of rural labor, the daily life of the peasants going about their routine provided an endless source of inspiration for both paintings and his exquisitely rendered pastels. In this pastel Millet took as his subject a young shepherdess focused intently on her needlework while her flock of sheep grazes on the plain behind her. It is a familiar motif in Millet’s oeuvre, one that embodies the rustic virtues of simplicity and hard work that he admired. Yet it is an oddly melancholy image. The life so lovingly depicted in Millet’s work was already in the process of vanishing, imbuing it with a sense of nostalgia and poignancy.

Kimberly Jones is associate curator of French paintings, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., and co-curator of In the Forest of Fontainebleau.