Fawning Over Flora: Eighteenth-Century Botanical Illustrations

During the seventeenth century, interest in scientific discoveries became a worldwide phenomenon, prompting ventures to uncharted lands in search of natural curiosities. The passion for collecting meant that the study of natural history was no longer confined to scholars but had moved into the domain of a wider public. By the third quarter of the eighteenth century, prints poking fun at the idea of traveling the globe in search of such things as small insects were circulating the English Empire. In The Fly Catching Macaroni (Fig. 1), the naturalist Sir Joseph Banks (1743–1820) is depicted balancing one foot on each of the earth’s poles while struggling to capture a butterfly. Banks was a perfect subject for such satire as he had taken part in several well-known expeditions and served for forty-one years as president of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge.

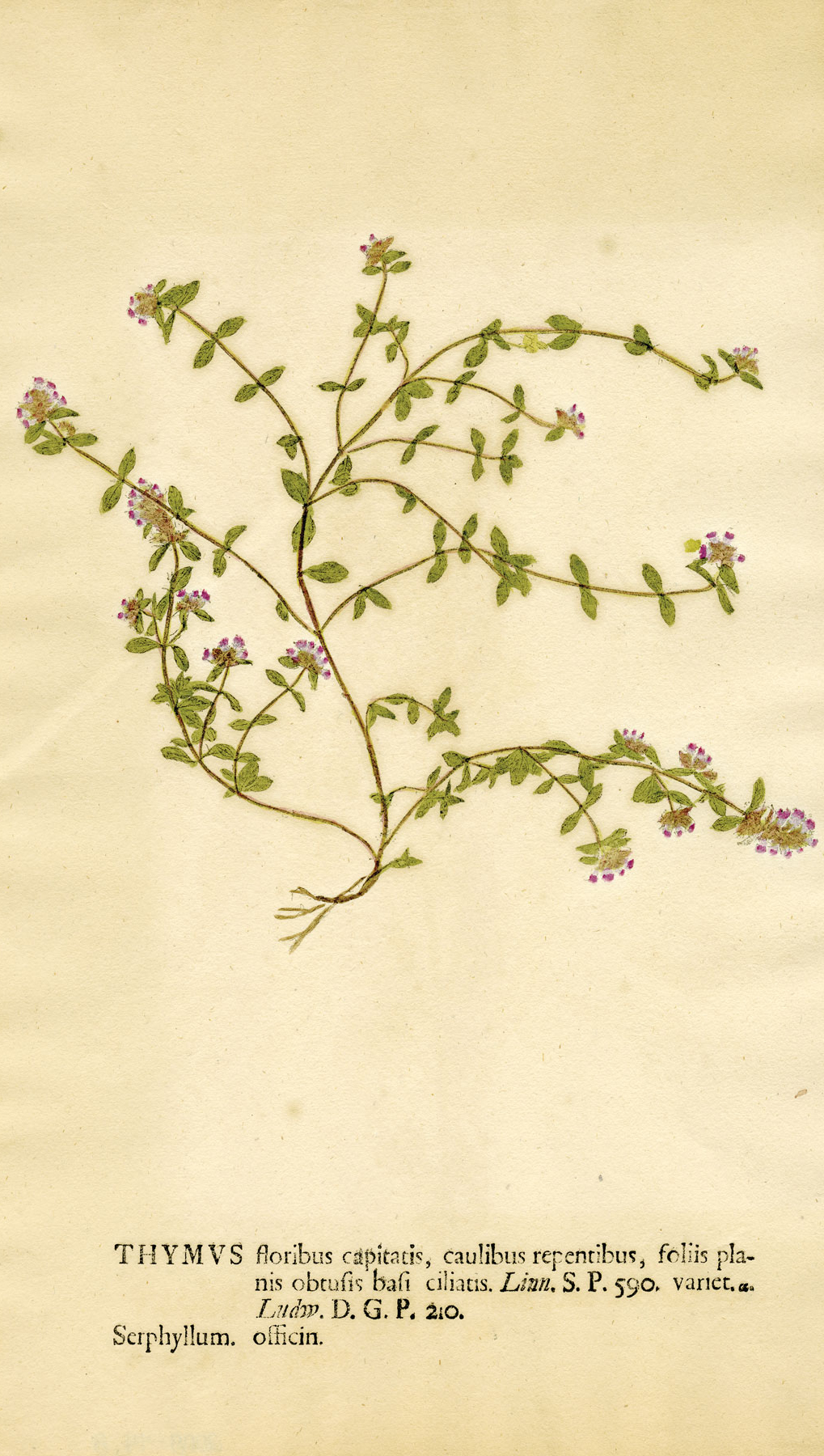

Books, called herbaria, which focused on the study of botanical specimens, were produced in central Europe as early as the late fifteenth century. These books contained woodblock depictions of plants intended to assist botanists with the identification of species. Due to the lack of detail woodblock prints afforded, the identification process largely relied on the written text that accompanied the images. By the late seventeenth century, however, advances in printing allowed the images to stand alone as aids to identification.

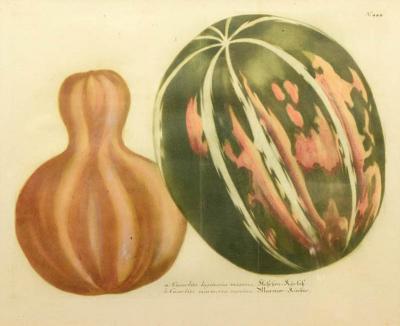

One of these advances was made in 1729, when Johann Hieronymus Kniphof (1704–1763), a German physician and botanist, developed a method for creating botanical images by using the plant itself. After the specimens were harvested, Kniphof pressed and dried them. Once dried, he applied printer’s ink to the specimen and rolled it through a printing press (Figs. 2, 3), allowing the plant to be depicted as true to life as possible.

Explorations in England’s American colonies in the eighteenth century produced an outpouring of publications documenting previously unknown minerals, flora, and fauna. Naturalists, identifying and cataloguing new forms, published books that not only aided other naturalists in identifying specimens, but which also found a home in the connoisseur’s library (Fig. 4).

With botany no longer strictly a scientific pursuit, botanical illustrations became a thing of beauty as well as instruction. Like many naturalists trying to increase their income, English naturalist and watercolorist illustrator Eleazar Albin (1690–1742) gave drawing lessons. One of his pupils was William Byrd II (1674–1744) of Virginia, when Byrd was living in London between 1717 and 1719.1 Byrd later provided financial assistance for Albin’s publication, A Natural History of English Insects (1724), which contains one hundred hand-colored plates of insects on plants, each bearing a dedication to a subscriber. One of these plates is dedicated to Byrd, acknowledging Byrd’s financial support (Fig. 5).

Decades later, Byrd may have solicited engraving assistance from Albin when he was writing an illustrated history of America. Although Byrd’s history was never published, a series of copper plates, surely engraved to accompany Byrd’s manuscript, and likely based on sketches by Byrd, survives in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. One of those plates, given to Colonial Williamsburg by the Bodleian Library in 1938, illustrates the only known eighteenth-century elevation of the Governor’s Palace. Given Byrd’s interest in nature and in gardening, it’s understandable why he included such details as the oval beds and stone paths in the forecourt and the formal gardens with garden houses behind the palace (Fig. 6). Along the bottom of the plate, Byrd also depicted the clipped rows of topiary evergreens and bushes surrounding the Wren building, the main building of the College of William and Mary, Williamsburg.

Illustrating nature also became a pursuit of young women, whose focus may have been on replicating the beauty of the natural world rather than the understanding of it. The Duchess of Beaufort instilled her interest in botany in her children, and hired German-born botanist Georg Dionysius Ehret (1708–1770) to teach them watercolor painting. The most highly regarded botanical illustrator in England at the time, Ehret provided Beaufort’s youngest daughter, Lady Henrietta Somerset, with lessons in rendering flowers in watercolor and gouache on vellum. The botanical specimens grown in the gardens at the family’s Badminton estate surely would have provided the source for these paintings.

Known for his accurate and aesthetically appealing rendition of plants, Ehret’s skills were in demand by naturalists, publishers, porcelain manufacturers, and wealthy patrons alike. Ehret himself was influenced by the work of others in the field, among them, Barbara Regina Dietzsch (1706–1783). Born into a talented family of artists in Nuremburg, Germany, Dietzsch’s paintings are characterized by the use of dark, usually brown, backgrounds, which create a stunning contrast to the soft, delicate colors of her flowers (Fig. 7).

When assisting Mark Catesby (1682/83–1749) during the production of his Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands (1729–1747), Ehret chose the same characteristic dark background that Dietzsch had used. His first contribution to an English botanical book was his watercolor of the Magnolia grandiflora that appeared in Catesby’s work (Fig. 8). It is no surprise that his pupil Henrietta Somerset used the same technique when she depicted a delicate white magnolia (Fig. 9).

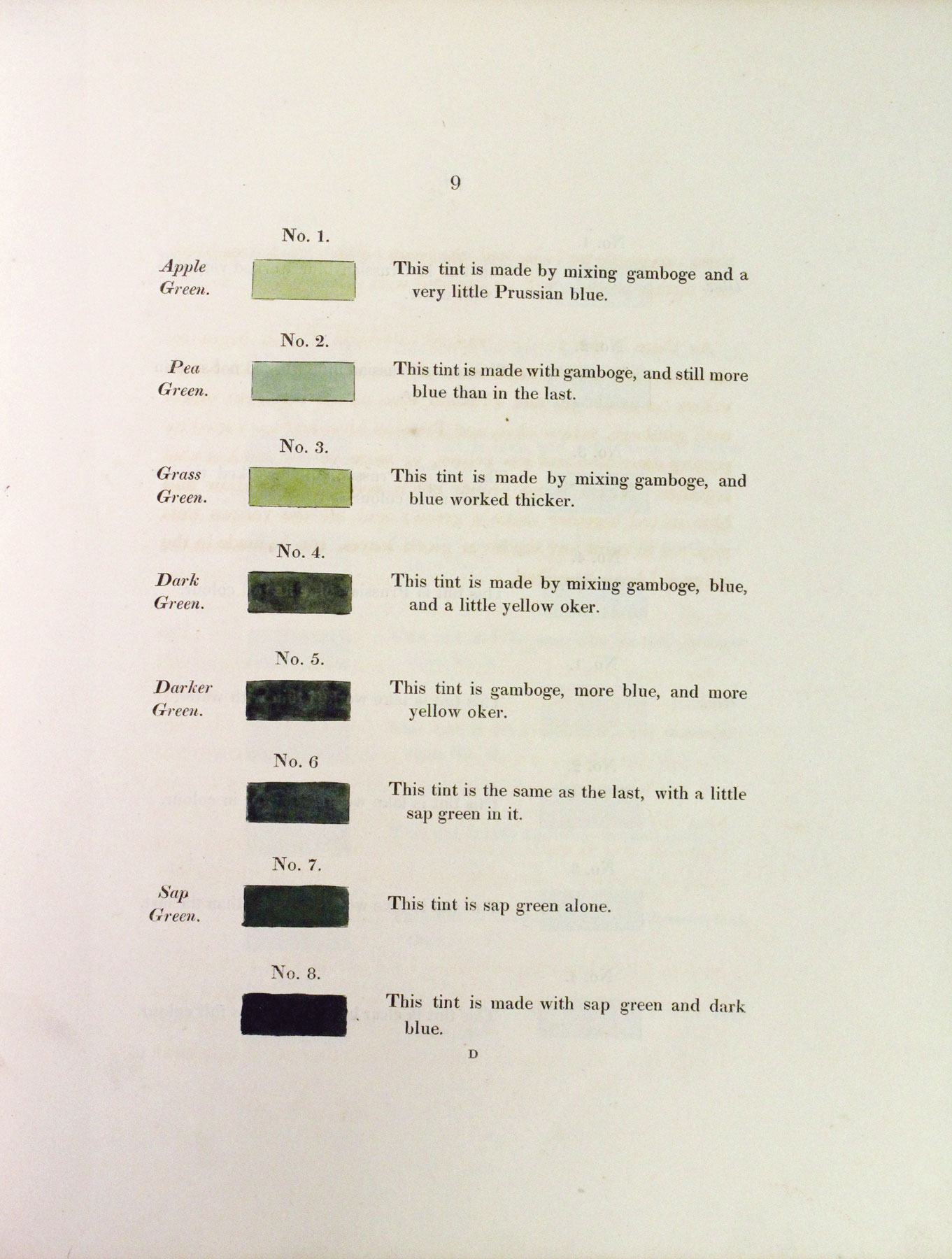

For young girls who didn’t have the opportunity to study directly under artists of Ehret’s caliber, instructional books, such as George Brookshaw’s New Treatise on Flower Painting (1818) provided complete directions for drawing and coloring botanical illustrations (Fig. 10). The purpose of Brookshaw’s Treatise, as its first edition claimed, was so that “those ladies who subscribe to this work may meet with as little difficulty as possible” in learning the best methods for rendering leaves, branches, and flowers.

Brookshaw addressed the lack of drawing fundamentals taught to women who had a “general inclination” for flower painting. In his introduction, he expressed the belief that ladies, “would sooner arrive at perfection than men, were they taught its proper rudiments,” and provided his readers with the basics of line and form needed to create botanical shapes.

Brookshaw also included instruction on how to mix tints to achieve the exact colors required to effectively create botanical illustrations. Several pages in his book illustrate the variety of shades he mixed together to create the beautiful watercolor flowers that appear in the rest of the book (Figs. 11, 12).

The symbiotic relationships between teacher and pupil seen in the early part of the eighteenth century and the instructional books that gained popularity in later decades reveal the growing interest in the natural world. What had started as an investigative aspect of the botanist or artist profession had become a trans-Atlantic interest for the gentry and the middle class.

Birds, Bugs, and Blooms: Observing the Natural World in the 18th Century, which runs through September 5, 2016, at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum, Colonial Williamsburg, focuses on the shift in botanical illustrations from pure science to an aesthetic hobby by examining a range of illustrations from 1590 to 1818. For information, call 757.220.7724 or visit www.history.org.

Katherine Teiken is assistant curator of prints, maps, and paintings, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art and AFAmag are affiliated with InCollect.com.

![Fig. 6: Modern engraving from the original copper plate of Williamsburg buildings, flora and fauna attributed to William Byrd. Colonial Williamsburg; Gift of the Bodleian Library in 1938 (1980-103 [R]).](../sites/uploads/Teiken_Fig6.jpg)