Fitz Henry Lane's Yacht America from Three Views: Vessel Portrait or Artist's Concept

This archive article was originally published in the Summer/Autumn 2010 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

- Fig. 1a: Thomas Goldsworthy Dutton (1819–1891)/Day & Son, The Yacht America Winning the Royal Yacht Club Cup at Cowes in the Match open to Yachts of all Classes and Nations, August 22, 1851. From the original sketch taken on the spot by Oswald Brierly. London. Published Octr 22nd by Ackerman & Co., 96 Strand. Colored lithograph, 19-3/8 x 27-3/4 inches. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum (M13340).

The schooner yacht America has been the subject of more paintings than any other pleasure or commercial vessel, perhaps rivaled only by the frigate Constitution. In 1851, the year of her victorious race off Cowes, England, she was portrayed by many of the most noted American and British marine artists of the day, and remains a favorite subject in paintings by many of today’s marine artists.

Conceived at the instigation of an English businessman, built in one of New York’s foremost shipyards, and sailed by a syndicate of New York yachtsmen, the America was intended to demonstrate the United States’ shipbuilding skill at Prince Albert’s Great Exhibition at London in 1851. America was designed by George Steers, who was then employed at the shipyard of William H. Brown and assigned by Brown to supervise the schooner’s construction. Brown had agreed to build the vessel under a contract that made him its owner unless or until the syndicate decided it had a winner and agreed to purchase it. After different trial races, America was purchased by the syndicate and sailed to England to race for, and win, a trophy which we know today as the America’s Cup.1

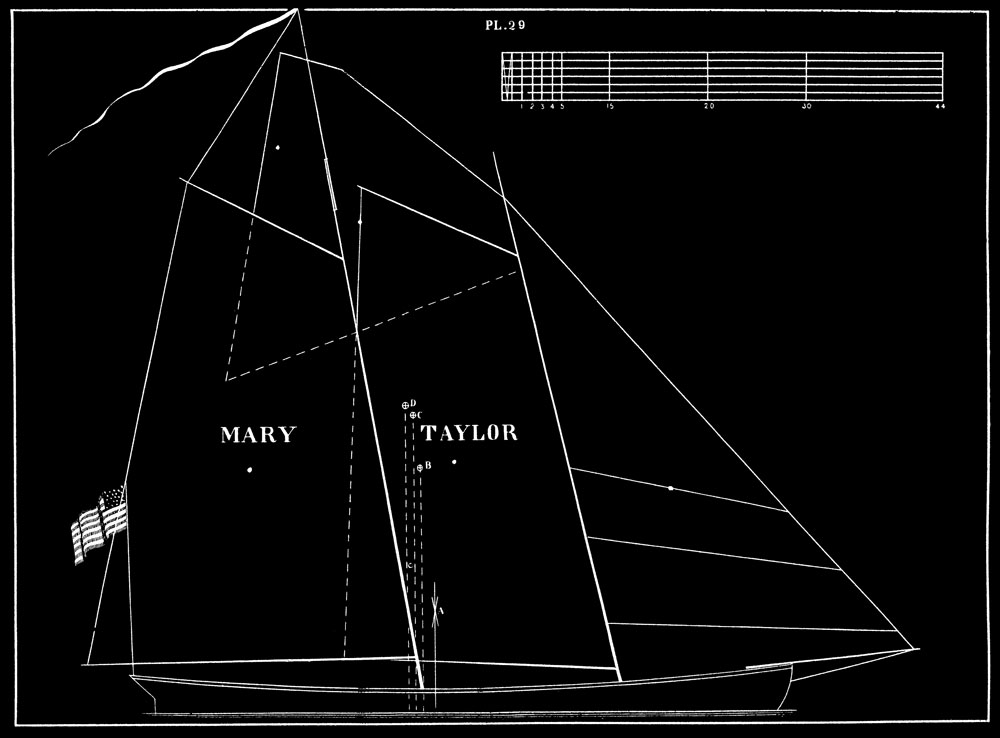

Two paintings of America are associated with Fitz Henry Lane (1804–1865). The more widely known painting, signed by Lane and dated 1851, is based on the lithograph by Thomas G. Dutton (1819–1891), which in turn was copied from an eye-witness drawing by Oswald Brierly (1817–1894) (Figs. 1, 1a).2 The other is an undated attribution to Lane, showing the yacht under sail in three views (Fig. 2).3 When, in 2009, the latter painting was loaned for public display for the first time at the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester, Massachusetts, it raised a number of important questions.

For Three Views, the attribution to Lane is strong for reasons of close attention to correct ship handling and details of rigging and sails. Lane was without peer (after the departure of Robert Salmon) in his attention to wind direction and velocity, making sure that cloud formations, sail trim, wave patterns, and minor details of flags, smoke from steamships, and buoy pennants are in close agreement. Similarly, the play of light on sails shows his thorough understanding of how light reveals sail contours, casts shadows on overlapping sails, and the translucency of canvas when backlit. Combining these effects with Lane’s mastery of hull form and proportions of rig, we see a brilliant demonstration of Lane’s mastery of nautical imagery.

A close examination of Three Views reveals discrepancies of detail between the artist’s depiction of America and other reliable pictures and plans of her as fitted out in her first year. Differences include details of rigging (Figs. 2, 4); the deck arrangement (Figs. 3, 4); and the ornamental carvings at the bow (Figs. 1a, 3) 4 and stern (Figs. 5, 6). Since these discrepancies do not exist in Lane’s 1851 version of the Dutton lithograph (figs. 1, 1a), it is conceivable that Yacht America in Three Views was executed earlier, and was based not on the actual finished vessel, but on incomplete information provided while the yacht was under construction or even still at the design stage.

Lane was clearly depicting America before her arrival in England. The steam vessel in the extreme right of the background (Fig. 7) is a large side-wheel towboat flying the American flag; the small boat in the left foreground (Fig. 8) is an American dory, then widely used in the coastal fisheries from Long Island north to the Canadian maritime provinces. These two craft, combined with the low rolling coastal terrain in the background, suggest offshore of western Long Island and not the rugged Cowes coastline as the likely setting. Following her victory at Cowes and a couple of other races, America came under British ownership, not to return to the United States until 1862.5 Her appearance from that date is documented in photographs, ruling out any possibility that this painting depicts her in a later state.

Perhaps the most persuasive evidence for an earlier dating is the flag flown at America’s masthead in the right view (Fig. 9). The pennants in the middle and left views are blurred, but the house flag with the letter B is clearly delineated, without doubt the owner’s initial. No other person involved with America’s construction or syndicate ownership had a last name with that initial. Moreover, as noted above, the contract for building the yacht made Brown the sole owner until the contract terms were met and the vessel was sold. A shipbuilder’s house flag (really a business logo in flag form), was certainly appropriate in this circumstance.

Period documents provide evidence of Brown’s sole ownership of America until the date of her sale on June 20, 1851. When registered at the New York customs house three days previously, Certificate No. 290, dated June 17, 1851, gave “William H. Brown, only owner of the ship or vessel called the ‘America,’” adding that she was built at New York during the year 1851 under the direction of Brown, master builder.6

In 1849, Brown hired George Steers as his chief loftsman,7 and in the following two years had Steers design yachts and pilot schooners, which went on to set standards for seaworthiness and speed.8 Steers designed America as he had designed his previous, and later, vessels: by carving a half-hull model that could be disassembled and traced to provide offsets (measurements of breadth at specific intervals) for shaping the molds (full-size patterns) for the hull frames. No drawn plans as we know them today were made after the hull had been framed. After examining the hull in this stage, client and builder could then better judge the available space and how best to apportion it.9

Similarly, Steers’ original sail plan for America was little more than outlines of the sails, including the masts and spars superimposed over a simple profile of the hull. Details were left to the sparmakers, riggers, and sailmakers who drew from their knowledge and experience. Steers did not get around to drawing a sail plan of America until 1851, and it was sent to the sail maker in whose loft it remained until discovered in the 1930s (Fig. 10).10

Assuming Lane was commissioned by Brown to paint a portrait of a proposed or partially built yacht, with only a half-model and some incomplete sail plans to study (Fig. 10), he would have been very much on his own. If a copy of the plan was made for Lane’s use, there is no record of its existence. But presumably he would have gone to New York to inspect and sketch Steer’s half-model and refer to existing sail plans of pilot schooners. Under this scenario, when could Lane have been in New York to discuss this project?

The year 1850 was one of Lane’s busiest years. He made trips to New York, Baltimore, possibly Puerto Rico, and to Maine. Travel to New York was likely taken in the late spring in time for the openings of the Düsseldorf School and the American Art Union exhibitions in New York, where several of his most recent paintings were hung to considerable acclaim.11 While in New York, it is quite possible that his presence came to the attention of Brown, by then in search of an artist to create an image of the proposed schooner. For Brown, with his unerring sense of how to attract business, only a first-rate artist would have done.

By the summer of 1850, Lane was traveling and sketching in Maine, probably from the beginning in August to early in September.12 We know he worked on several major paintings based on his sketches of New York and other southern ports made earlier in the year. Among them is the monumental 36 x 60-inch panoramic view of New York harbor, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. So it is unlikely that he made another trip to New York, and since no correspondence exists between Lane and Brown or Steers for this period, it is most likely that meager plans already described are all with which he had to work.

Meager though Lane’s source material may have been, he made the most of the information. The subtle shading and highlights of the hull in each view leave no doubt that he understood America’s hull form perfectly. Lane had to have seen and studied Steers’ half-model very carefully at Brown’s shipyard during his late spring visit to New York, when he certainly would have had the opportunity to see and measure sail plans from other Steers’ designs, making adjustments for size and proportion of the designer’s advice.

The foregoing considered, it seems possible, even likely, that Lane’s painting, Yacht America fromThree Views, was commissioned by William H. Brown in 1850 as an artist’s concept of a proposed schooner yet to represent American shipbuilding at the Great Exposition in 1851. Brown may have had it in mind for the syndicate that eventually commissioned him to build it, or perhaps to attract other clients. Having such a painting to show to his clientele was certainly in keeping with his business methods. In the tight circle of New York’s yachtsmen, such a painting would have been noticed and its purpose appreciated.

Artists’ renditions of new commercial products tend nowadays to be derided as mere “commercial art.” But in the nineteenth-century, respected artists like Lane engaged in such projects alongside their more serious work, and this reason for painting ship portraits warrants serious consideration as advertising. Painted before the yacht was completed, Fitz Henry Lane’s Yacht America from Three Views would have served William H. Brown’s efforts to attract business and funding for the building of future vessels of this type and purpose. The only thing that is missing from this argument is irrefutable evidence in the form of a contract or correspondence between the artist and Brown. But perhaps evidence of this sort may yet come to light.

-----

Erik A. R. Ronnberg Jr. is a model maker and nautical historian whose research has led to extensive study of marine art, particularly ship portraiture, from the seventeenth through twentieth centuries. In the past he served as curator at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, curatorial advisor at the Essex Shipbuilding Museum, board member of Cape Ann Museum, and editor of Nautical Research Journal.

This article was originally published in the Summer/Autumn 2010 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. M. V. and Dorothy Brewington, The Marine Paintings and Drawings in the Peabody Museum, rev. ed., (Salem, MA: Peabody Museum, 1981), 165.

3. Yacht America From Three Views is better known to yachtsmen and students of yacht design than it is to most art historians and collectors. It was first publicized by its then-owner the yacht designer L. Francis Herreshoff (1890–1972), who used it in a serial article (later published in book form) on yachting history (L. Francis Herreshoff, An Introduction to Yachting (New York, 1963), 60, 61). On Herreshoff’s death, the painting was consigned to a dealer who sold it to the late Glen Foster, a businessman with a stellar background in yacht racing (Alan Granby [ed], A Yachtsman’s Eye, [Philadelphia and New York, 2004], 174, 175). Since Foster’s death, it has been in a private collection.

4. America’s trailboards were unique to that vessel at the time of her building, and subsequently used only on Steers-designed ships, notably the clipper ship Sunny South, built in 1854. With no existing vessel to copy, Lane may well have relied on Steers’ preliminary design sketches for this detail, not realizing that the trailboards as made would be larger and more prominent.

5. Rousmaniere, 42.

6. See John H. Morrison, History of New York Ship Yards (NY: Sametz, 1909), 125.

7. Ibid. In this period, the title of Loftsman combined the work of designing a vessel (usually by carving a half-model) and deriving from the model the shapes of the frames that were “lofted,” i.e., enlarged to full size patterns (molds) for making the frame components. This process required a large floor space, usually the loft of a large building on or near the shipyard, hence the terms “loft” (verb), “lofting,” “mold loft,” and “loftsman.”

8. Rousmaniere, 9, 10.

9. Howard I. Chapelle, The National Watercraft Collection, second edition (Washington and Camden, 1976), 8–12.

10. Rousmaniere, 16, 17.

11. John Wilmerding, Fitz Hugh Lane (NY: Praeger Publishers, 1971), 42–44.

12. Wilmerding, 52.