Folk Art & American Modernism

In the 1910s, the antiquarians and ethnologists who had been collecting folk art in the nineteenth century were joined by Modernist artists who began acquiring American folk art for its artistic qualities. These artists—and the dealers, curators, art critics, and collectors who shared their interest in folk art—established a collecting tradition different from that of their predecessors. They accumulated furniture, hooked rugs, paintings, weathervanes, and decoys both as furnishings and as examples of indigenous American art. The artists valued these objects for their formal artistic qualities and made analogies between folk art and the Modernist art they had studied in Europe and were pioneering in America. Additionally, they viewed the simplicity of the furnishings and paintings they collected as evidence of a uniquely American character, one that shared characteristics with their own work. In collecting these works, they were seeking to document a continuous American artistic tradition of which they could consider themselves a part.

Robert Laurent was one of the earliest artist-collectors of American folk art. Karfiol has depicted Laurent’s two sons in the living room of the Laurents’ Maine home, surrounded by antique furniture and three folk paintings, one of which is Girl in White with Cat (see fig. 2). The other two are Portrait of a Young Boy Seated with His Dog on a Painted Floor by an unidentified artist, and Dover Baby, also by an unidentified artist. All three works are in the exhibition; this is the first time they have been reunited since they left the Laurent family.

Among the artists, collectors, dealers, curators, and art critics who, in the first half of the twentieth century, identified, defined, publicized, and fostered appreciation of American folk art, were the artists who summered at the colony that artist and teacher Hamilton Easter Field established at Ogunquit, Maine, in 1911. Robert Laurent, Field’s protégé, was perhaps the most avid of these artist-collectors (Figs. 1, 2). His friends Bernard Karfiol and Yasuo Kuniyoshi were among those who joined him in searching the surrounding countryside for antique treasures with which they furnished their homes and studios—many of them converted fishing shacks. When they returned to New York at the end of the season, they often took folk art with them, exposing their friends and acquaintances to this new category of collecting.

While not part of the Ogunquit summer colony, William and Marguerite Zorach were friends with many of its members and were also early folk-art enthusiasts. They filled their old sea captain’s house in nearby Bath, Maine, with hooked rugs and simple country furniture; Marguerite stenciled folky patterns onto the walls of the kitchen and living room. The work of both Zorachs was influenced by folk art—Marguerite in her use of brilliantly colored woolen yarn for hooked rugs and tapestries (Fig. 3) and William in the employment of the direct-carving method in his sculpture.

Juliana Force, director of the Whitney Studio Club, was an early and ardent folk art collector (Fig. 4); she introduced many others in the New York art world to the genre. Under her auspices, the artist Henry Schnakenberg put together the first exhibition of American folk art, shown at the Club in 1924. Force and Charles Sheeler, also a Whitney Studio Club artist, were pioneer collectors of Shaker furniture, examples of which appear in Sheeler’s paintings and photographs of interiors of the 1920s and 1930s.

Elie Nadelman, a Polish sculptor who emigrated to the United States in 1914, and his wife Viola, together formed what was undoubtedly the most impressive folk art collection in America in the 1920s and early 1930s (Figs. 5, 6). Many of the objects in the collection echoed the supremely simplified lines of Nadelman’s sculpture (Fig. 7). Acquired in both Europe and America to illustrate the influence of the Old World on the New, the collection was displayed from 1926 through 1937 on the Nadelmans’ Riverdale, New York, estate in a specially built museum. Reverses caused by the Depression forced the couple to begin selling individual objects in the early thirties; in 1937 they sold their entire collection to the New-York Historical Society.

Isabel Carleton Wilde was a passionate collector who amassed such a notable collection of folk paintings, watercolors, weather vanes, and carvings that it may be said to rival that of the Nadelmans—if not in size, certainly in quality (Fig. 8). Wilde was also a dealer in antique household furnishings and an old-house restorer, advertising in 1926 that she had moved her shop, opened the previous year, to an old

house she had just renovated near Harvard Square in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She later had a shop on Sutton Place in Manhattan, and pieces from her collection were exhibited in several New York galleries. The Depression and her husband’s illness, however, forced her, like the Nadelmans, to part with her beloved folk art in the 1930s and 1940s. Much of it was bought by the dealer Edith Halpert, and through her found its way into important collections of folk art.

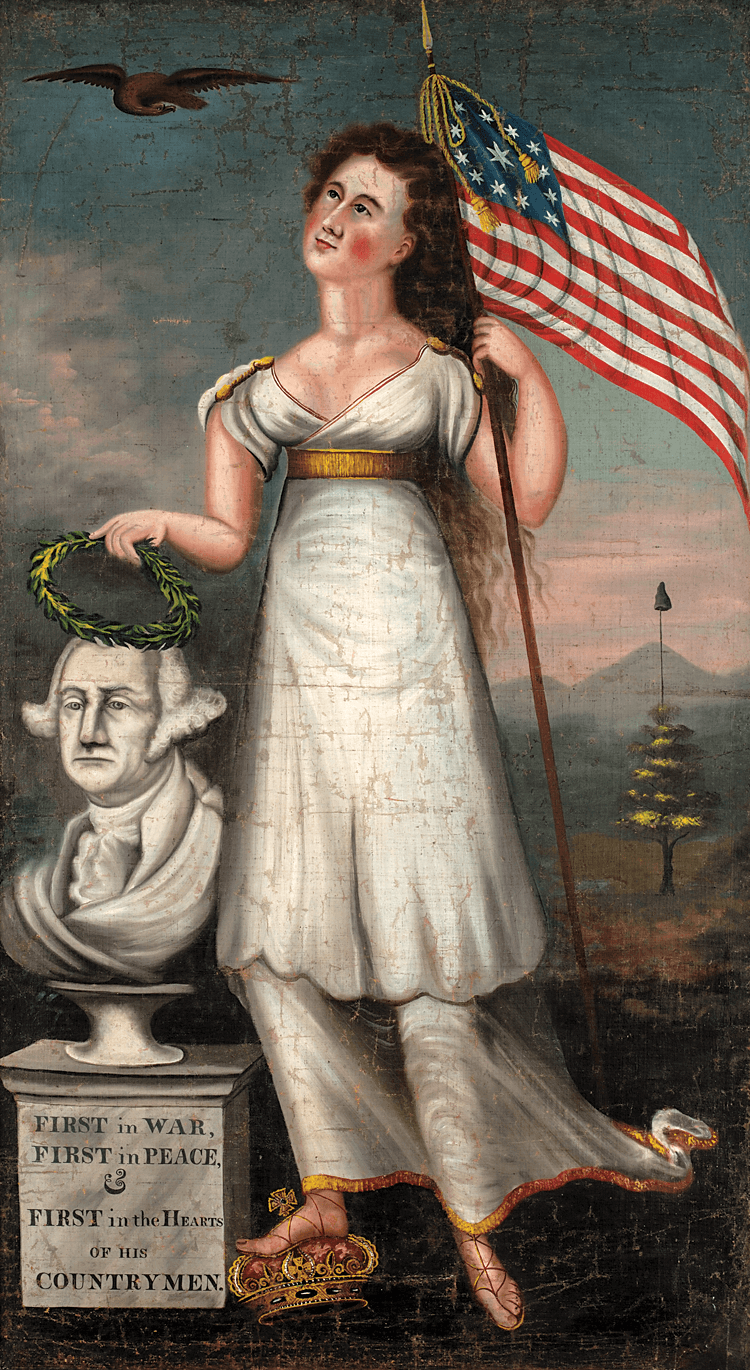

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, Holger Cahill, and Edith Gregor Halpert made up the triumvirate that put folk art on the road to acceptance as art rather than as history or ethnology. With Mrs. Rockefeller as patron, Cahill as theorist, folk-art finder, and curator, and Halpert as dealer and promoter, these three introduced art-conscious Americans to the newly recognized genre and made collecting it respectable—even, in some circles, fashionable (Figs. 9, 10). The Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum in Williamsburg, Virginia, of which Mrs. Rockefeller’s collection was the foundation, is a tribute to the vision of all three.

Cahill was head of the Federal Art Project of the WPA. Among the department’s projects was the creation of the Index of American Design, an encyclopedic collection of visual images of American folk and decorative art that is now at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. This Depression-era project was created to give work to unemployed artists and to fill the need for an archive of indigenous designs. According to Cahill, the Index was intended to clarify “the native background of the arts,” and to get “people all over the United States interested in art as an everyday part of living and working.” Holger Cahill and his Index colleagues became the ultimate folk art collectors, documenting work from the participating thirty-four states and the District of Columbia. Folk and vernacular art, particularly of New England and the Middle Atlantic states, was recorded in artists’ “renderings”—colored drawings often so beautifully executed as to be works of art in themselves. Numerous exhibitions of the Index renderings were held throughout the country, bringing American folk art to new audiences.

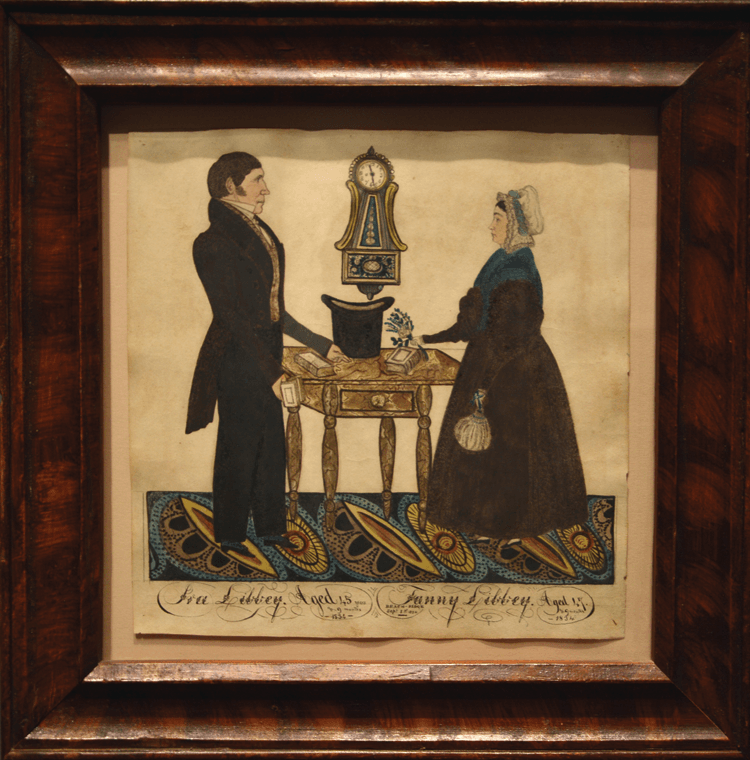

The interest in collecting folk art also resulted in important early publications. Art historian and editor of Art in America magazine, Jean Lipman, along with her husband Howard, began to buy folk art in 1937 to furnish their Connecticut farmhouse. Jean’s conviction that their folk art was serious, led to the publication of American Primitive Painting in 1942. This was the first significant book on the subject and the first of Jean’s many books and articles on folk art topics. Important parts of the Lipmans’ collections are now in the New York State Historical Association’s Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York (Figs. 11–13) and in the American Folk Art Museum in New York City. In 1974 she organized The Flowering of American Folk Art for the Whitney Museum, a comprehensive exhibition that was both a summation of the half century of collecting since the first folk-art exhibition at the Whitney Studio Club as well as the launch of a new era of interest in folk art. In 1980, again at the Whitney, she presented American Folk Painters of Three Centuries—another “first”—an exhibition devoted to thirty-seven folk artists whose work and life stories had been rescued from obscurity by the kind of dedicated research Jean Lipman encouraged and practiced during her long career.

Folk Art and American Modernism, on view through December 31, 2014, at the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York, comprises approximately eighty objects. The material is supplemented by photographs of the artists and collectors, the interiors of their homes, and early folk art exhibitions. This exhibition is based on the “Folk Art and Modern Art” section of Elizabeth Stillinger’s recent book, A Kind of Archeology: Collecting American Folk Art 1876-1976. For information visit www.fenimoreartmuseum.org or call 607.547.1400.

Elizabeth Stillinger is a writer, researcher, and editor in the fields of decorative and folk art and collecting. She is the author of six books, including The Antiquers (1980) and A Kind of Archeology (2011). Ruth Wolfe worked as an editor with Jean Lipman at Art in America magazine and at the Whitney Museum. She has edited numerous folk-art publications, most recently the two-volume Expressions of Innocence and Eloquence: Selections from the Jane Katcher Collection of Americana (2006, 2011).

This article was originally published in the Winter 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. InCollect.com is a division of Antiques & Fine Art, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing.