Frozen In Black And White: The Photography Of Irving Penn

- Irving Penn, San Francisco Big Brother and the Holding Company and The Grateful Dead, 1967. Platinum palladium print. Offered by Robert Klein Gallery (Boston, Mass.).

In the 1967 photograph of San Francisco-based rockers (right), offered by Robert Klein Gallery (Boston, Mass.), members of The Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company are arranged in a four-tier composition, two guitarists clutching the instruments of their trade as they and their fellow band members pose for the camera. They all seem to inhabit a self-contained universe, frozen in black and white against a theater curtain marked with an indistinct, cloudlike pattern.

The image, by Irving Penn (1917-2009), is imbued with it a hypnotic quality, dispensing with superfluous details to present a composition that is cool and restrained. This master of minimalism was widely admired for his understated aesthetic, compositional rigor, and, most of all, willingness to buck the dictates of his profession. In this, as in other works, he refrained from dynamic, or “action,” shots in favor of static portraits that underscored the dignity of the sitter(s).

On April 24, The Metropolitan Museum of Art will unveil a major retrospective of the artist’s work to coincide with the centenary of his birth. The show will be anchored by selections from some 187 photographs that have been promised to The Met by the Irving Penn Foundation, as well as fifty prints already in the museum’s collection. This is the third exhibition at The Met dedicated to the photographer, following major shows in 1975-76 and 2002.

|

|

“Irving Penn is one of the most renowned photographers of the 20th century,” says Robert Klein, of the eponymous gallery in Boston. ”While his most recognizable photographs derive from fashion assignments for Conde Nast, he also invented approaches to the genres of still life, ethnographic, and portrait photography. The subject of countless one-person exhibitions in galleries and museums worldwide, his market presence, too, has been among the most consistent of any artist in history. His spare, elegant aesthetic is immediately recognizable in the hand-crafted platinum/palladium prints that stand at the pinnacle of photographic craftsmanship.”

Born in 1917 to Russian immigrants in Plainfield, N.J., Penn studied under Alexey Brodovitch at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Arts, where he was exposed to the formal strategies that came to define modernism. After a dalliance with painting—Penn traveled to Mexico to paint in 1941, but later destroyed his canvases—he was hired by Alexander Liberman, art director at Vogue, to assist with layout and production. At the urging of his boss, who said of the photographer that he had “an eye that knew what it wanted to see,” Penn began chronicling the latest trends for the pages of Vogue, developing an economic style that departed radically from the elaborate compositions of competitors like Richard Avedon (1923-2004). In this Fashion Study (ca. 1949), from Robert Klein Gallery, a model in black hat and dress looks at the camera with a sly, almost impertinent, expression. She is divorced from her surroundings, an enigmatic figure floating against a blank background.

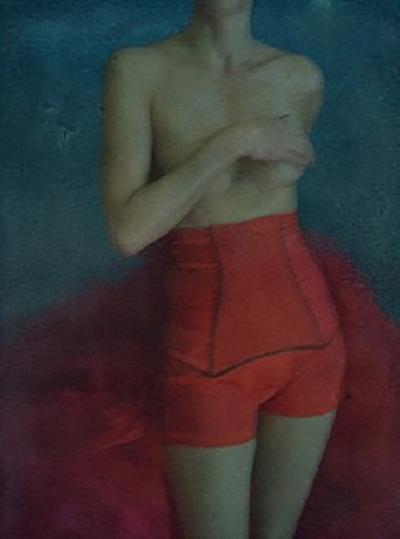

Penn had the eye of a sculptor, modeling volumetric forms in black and white. This is most evident in his corpulent nudes, shot at close range to register the texture and temperature of exposed flesh. In the words of Penn, his nudes were meant as a riposte to “the slickness of the image,” or the facile quality of images that appeared in glossy magazines. In Nude No. 57, offered by Robert Funk Fine Art (Miami, Fla.), a reclining nude is seen from chest to ankles, extending a foreshortened knee toward the camera. Many of Penn’s nudes were printed with experimental methods, lending the photographs an indistinct, velvety quality.

|

|

In addition to staged compositions in the studio, Penn was drawn to scenes of urban decay, shooting photographs of sidewalk debris. His "Cigarette" series, one of the highlights of the show at The Met, is a meditation on refuse, zooming in on the fibers of the discarded butts. Once again, Penn has combined his bare-bones aesthetic with inventive techniques, using a platinum process that involves hand-sensitized artist’s paper affixed to an aluminum sheet.

While Penn dedicated most his practice to black and white, he did produce shots with saturated colors, as with Still Life with Watermelon, NY, from Robert Funk Fine Art, which shows a bunch of grapes, wedge of watermelon, crumpled napkin, crusty heel of a baguette, and a severed mushroom cap. The composition is notable for the presence of a housefly, adding an element of decay to the cornucopia and perhaps paying homage to their inclusion in Old Master still lifes.

In many ways, Penn was a contradictory figure, a taciturn man who engaged with Hollywood starlets, a witness to high couture who was “unspoiled by European mannerisms or culture,” in the words of Liberman. The promise of the exhibition at The Met, the most comprehensive show of Irving Penn to date, is to synthesize these disparate threads, offering new insights on one of the twentieth century’s most influential photographers.