Great and Mighty Things

Outsider Art from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection

For more than thirty years, Philadelphians Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz––he is a lawyer, she is a ceramicist––have been drawn to the work of self-taught artists, individuals who are not trained in art schools, do not earn a living as artists, and who, for the most part, have limited or no connection to the mainstream art world with its dealers, galleries, collectors, critics, schools, and museums. During those three decades the couple has formed one of the finest collections of American outsider art in private hands. Intending that a wider public should eventually enjoy these works, they have made a promised gift of most of them to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This generous donation is celebrated by an exhibition, “Great and Mighty Things”: Outsider Art from the Jill and Sheldon Bonovitz Collection.

The show consists of close to two hundred works in various mediums, dating from the 1930s through the 1980s (with one piece from 2010), by twenty-seven artists of different ethnic backgrounds, from widely scattered, mostly rural places all over the country. Regional cultures and the richness of local character abound in these works, which show a variety of motivations and influences––from religious convictions to pop culture––and inspiration that draws on everything from memory, dreams, and the artists’ imaginations.

William Edmondson (1874–1951)

William Edmondson was born on a farm near Nashville, the son of former slaves, and began making art after retiring from his long-time job at a Nashville hospital. A devout Primitive Baptist, Edmondson had a vision sometime between 1930 and 1933 in which he said God appeared to him and talked about the gift of stonecutting he was going to confer on him. In a later vision he saw a tombstone in the sky that he believed God intended him to make.

In response to these events, Edmondson began carving tombstones and outdoor stone ornaments. When New York photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe introduced Edmondson’s work to Alfred H. Barr Jr., the director of the Museum of Modern Art, Barr perceived qualities in common with modernist art and held a small one-man exhibition in 1937 showcasing the artist’s carvings. Edmondson is today considered one of the most iconic self-taught artists the United States has produced.

Purvis Young (1943–2010)

Purvis Young grew up in Overtown, a once-thriving, historically African-American neighborhood in Miami, Florida, that had turned into a slum. Not receiving much education, he began drawing while serving a three-year jail sentence for breaking and entering. After his release, inspired by urban murals he had seen in books and magazines, Young began his own mural project in Goodbread Alley, Overtown, hanging dozens of his paintings edge to edge along a dilapidated stretch of the street. He addressed issues of racism, poverty, suffering, communal redemption, faith, and hope for salvation. Horses and trucks permeate Young’s work—representing freedom—along with boats, musicians, dancing figures, buildings, and large blue “all-seeing” eyes.

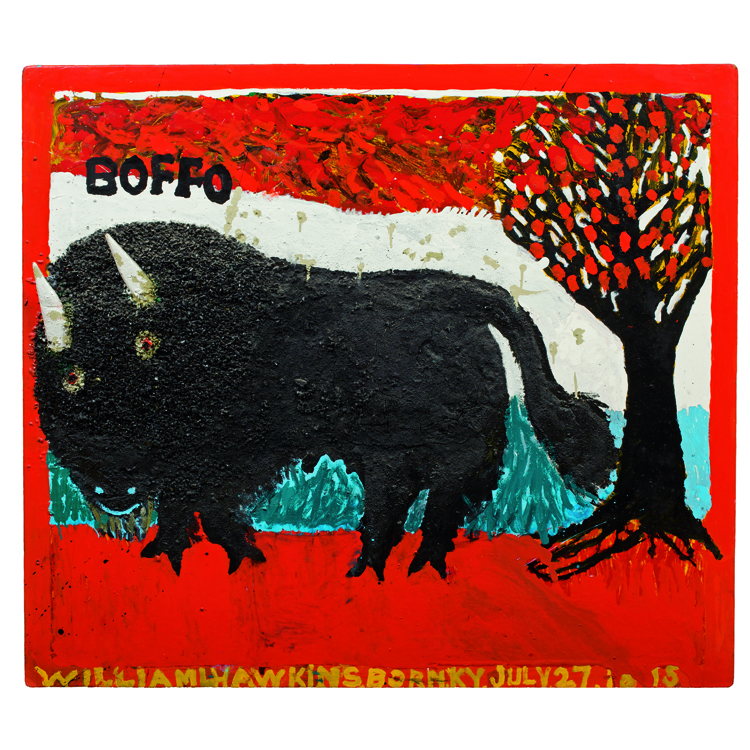

William Hawkins (1895–1990)

William Hawkins, raised on a farm and with only a third-grade education, settled in Columbus, Ohio, and held various jobs that ranged from plumber to truck driver to brothel manager. He began making art sometime in his thirties, frequently using magazines, newspapers, textbooks, and other print media as sources for his imagery. He also reinterpreted famous works of art and current events and depicted animals and Ohio landmarks.

Found plywood and Masonite panels and house paint were the artist’s primary materials, and he manipulated his paint with worn, stubby brushes. He sometimes incorporated into his compositions collaged reproductions of works by other artists, pages cut from print sources, and found objects such as strips of wood. When Hawkins was around eighty-six years old, he won first prize in the amateur artist division of the 1982 Ohio State Fair. After this success, he painted full time until his death in 1990.

Elijah Pierce (1892–1984)

It is hard to imagine today, when he is recognized as one of America’s best-known woodcarvers, that for much of his life Pierce was better known as a barber and Baptist preacher whose uncle had taught him to whittle as a child on a Mississippi farm. Using simple tools such as a pocketknife, a chisel, a piece of broken glass, and sandpaper, Pierce, made remarkable small bas-relief carvings, often of biblical scenes, his so-called “sermons in wood.“

Pierce showed in local exhibitions, but his work did not provoke wider attention until 1968, when the artist was in his mid-seventies. A graduate student in sculpture at Ohio State University spotted his work and became a strong advocate, and Pierce enjoyed a growing reputation from the 1970s on, with his pieces being shown at galleries and in museums.

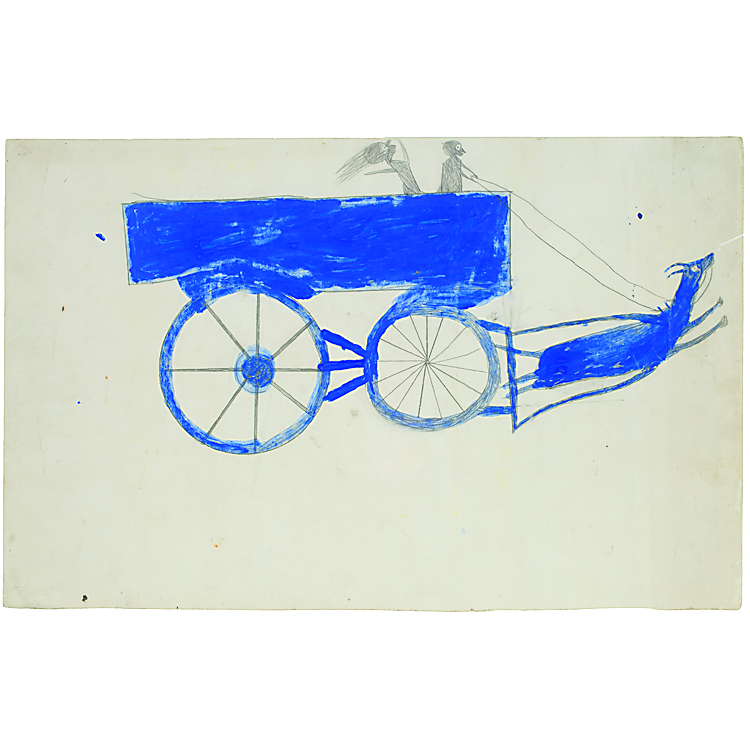

Bill Traylor (1853–1949)

The suddenness with which Bill Traylor began to make art, his advanced age (he was in his mid-eighties when he began), and the briefness of his artistic activity (three or four years) make him unique among the artists in the Bonovitz Collection. He was born a slave on an Alabama plantation and remained on the land as a farmhand for most of his life.

The drawings Traylor made between about 1939 and 1942 while living in Montgomery, Alabama, often homeless, reveal his genius for composing shapes on a page. His subject matter—people, animals, household objects, and what he called “exciting events,” lively scenes of people engaged in running, climbing, shooting, fighting, yelling, poking, and drinking—provide glimpses of a long-gone African-American culture in the rural Deep South. A young Alabama painter fortunately saved much of Traylor’s work and eventually shared it with the world.

All photography courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.