Green Mountain Idylls: Milton Avery’s Vermont

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Antiques & FIne Art magazine.

At first glance, it is just an old family photograph (Fig. 1). As it turns out, the informal snapshot, inscribed across the top margin, “Sally. Milton March. Vermont/ ’35,” is one of the few archival documents that connect the modern American painter Milton Avery (1885–1965) to Vermont. The photograph establishes a particular place and mood. A relaxed Avery is seated in the grass with his wife, Sally Michel Avery, an accomplished artist in her own right, and their two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, March—on what looks to be a perfect summer afternoon. The image captures a moment during the first of at least six extended summer holidays, between 1935 and 1943, that the Avery family spent in the small adjacent villages of Rawsonville and Jamaica, in the West River Valley, amidst the Green Mountains of south central Vermont. These Vermont visits proved to be a pivotal chapter in the development of the artist’s distinctive style.

The main evidence documenting the Averys’ time in the Green Mountains is the art he created as a result of his extended summer holidays there in 1935–1937, 1939–1940, and 1943. “Summer holiday,” a term borrowed directly from the title of one of Avery’s drypoints (Fig. 2), is a misnomer, for these visits sometimes extended from spring through summer into fall (Fig. 3), and hardly constituted a break from productive work. A notice in the October 11, 1935, issue of The Vermont Phoenix newspaper notes, “Artist and Mrs. Avery and little daughter, March, who spent the summer at Mrs. Emma Franklin’s, returned to their home in New York this week.” The Averys also made shorter visits to the area. Another notice in the October 13, 1939, issue of the same paper indicates that they stayed at the Franklin place for a few days earlier in the week, picnicking with Mr. and Mrs. Kingsbury and their children at Townshend State Park—likely the event depicted in Avery’s painting The Picnic, Vermont (Fig. 4). Avery’s painting bears comparison with Édouard Manet’s iconic early modern painting Le déjeuner sur l’herbe (Fig. 5). The reference was surely intentional as Avery was an assiduous student of art history.

The family photo we saw earlier also shows the Avery family having a picnic on the grass. Their complete sense of peace and ease exudes an air of intimate calm that echoes throughout much of the work Avery produced in Vermont. This is not the brash hedonism of Luxe, Calme et Volupté (1904) by Matisse, a painter with whom Avery is often compared. Rather, it echoes Charles Baudelaire’s declaration that artists should paint, not the heroic and grand, but the seemingly inconsequential and quotidian in “modern life,” which is all the more poignant for its “everydayness.” Avery’s “modern life” featured the Arcadian Vermont landscape and the leisure activities of a progressive middle class in the northeastern United States escaping the crush of city life and later, a world at war (Fig. 6). Though very far from Baudelaire’s mid-nineteenth-century Paris, Avery’s version of modern life equally sums up the thoughts and concerns of his particular time and place.

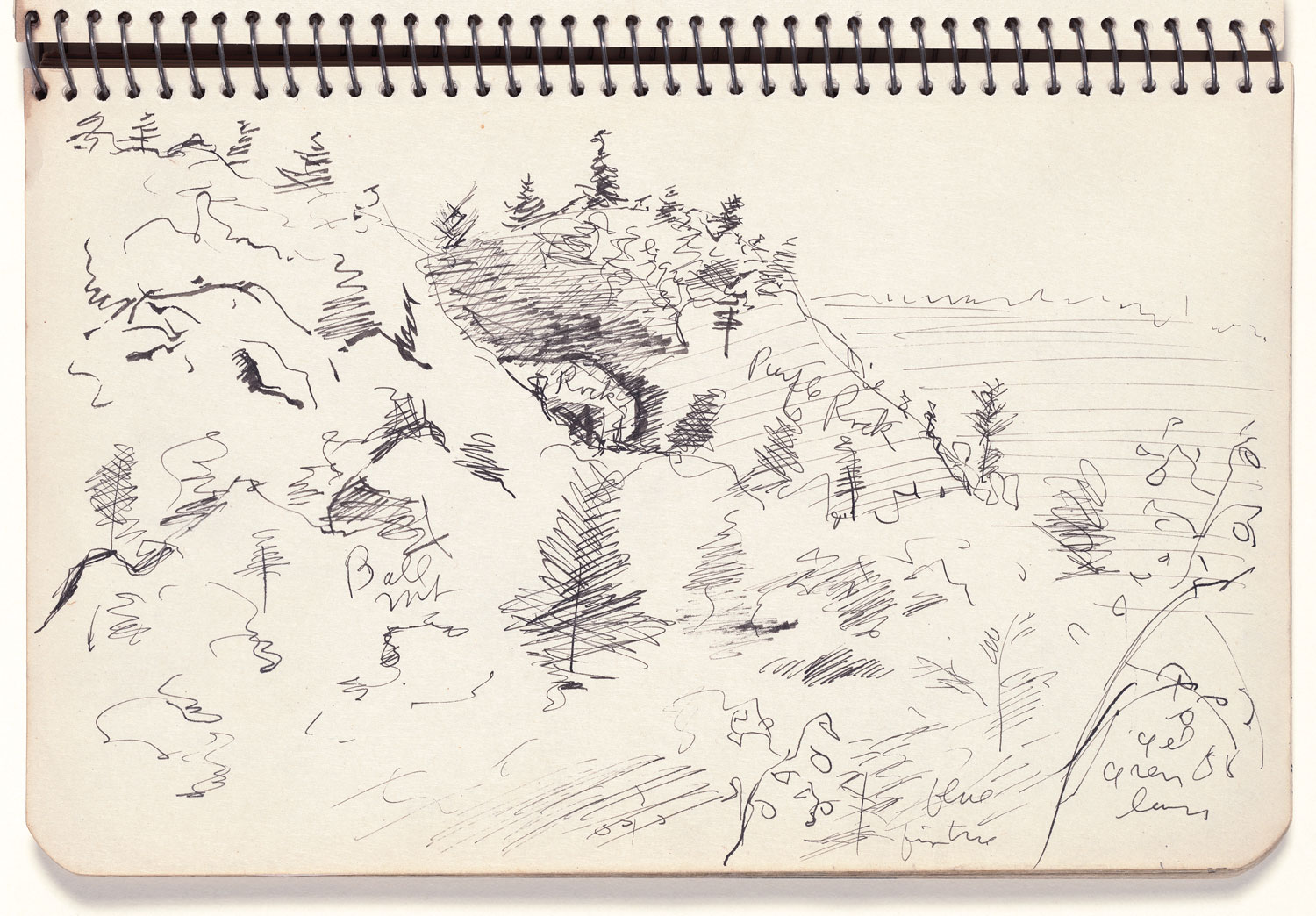

Avery worked voraciously while in Vermont. The artist himself noted, “In the country I get up at six o’clock and do a watercolor before breakfast, and three or four more during the day.” His process during his summers in the country involved creating watercolors or gouaches (Figs. 7–10), not from life, but based on plein air sketches in graphite, ink, and lithographic crayon. He translated this work into oil paintings in his New York studio during the winter months, sometimes years later (Figs. 11, 12). Drawing on his everyday experiences, the artist summarized his approach: “I work on two levels. I try to construct a picture in which shapes, spaces, colors form a set of unique relationships, independent of any subject matter. At the same time I try to capture and translate the excitement and emotion aroused in me by the impact with the original idea.”

A humorous anecdote related by Sally Avery about her husband’s painting Blue Trees (Fig. 13) provides insight into the tension in Avery’s works between their formal qualities, their emotive power, and their dependence on subjects drawn from the real world. She related how a business tycoon, Roy Neuberger, wanting to buy a painting and made a studio visit; nothing pleased him. Looking at one landscape, he exclaimed, “That tree is blue—I never saw a blue tree in Vermont.” To which Avery replied, “This was New Hampshire.” In fact, the painting, which Neuberger acquired, was based on studies executed in Jamaica, Vermont, looking south into the West River Valley from the slopes of Ball Mountain, into the area that is now largely occupied by Jamaica State Park. Though based on a recognizable slice of the real world, the contours of the most prominent mountains in the background have been exaggerated and others eliminated, emphasizing the other peaks’ rounded forms. As the critic Clement Greenberg noted, “As much as he simplifies or eliminates, Avery preserves throughout something of the specific, local, namable identity of his subject . . . it is never merely the pretext for a picture.” In Blue Trees, Avery translated an image of a real landscape into a sketch, then a watercolor, and finally, an oil. Through this process he maintained the scene’s basic compositional format while achieving a more specific and subtle definition of space, atmosphere, and form through color. Depending little on a slavish recording of reality, he was able, through the acuity of his vision, to capture the essence of the people and places he depicted.

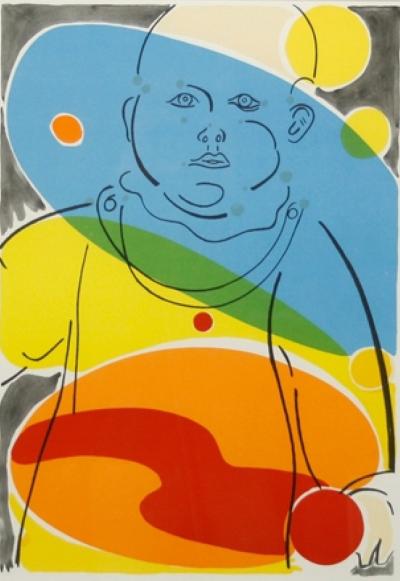

The Averys’ regular holidays in the Green Mountains ended after 1943. Though painted years later, Mountain and Meadow (Fig. 14) from 1960 is Avery’s latest canvas that can be definitively connected to direct observation of the Green Mountain landscape. The association is on the basis of a sketch and a watercolor, both dated 1958, and of Sally’s recollections of a roadside picnic as they were passing through Vermont. The work represents Avery at his late-career best, and is the type of painting by the artist, with its large swaths of luminous color, often cited as relating to the development of Color Field painting, which after a decade of gestation amongst Avery’s friends and colleagues exploded onto the scene in the early 1960s. Given Avery’s long-term friendships with Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, and Barnett Newman, this connection is not surprising. While Avery stuck with recognizable imagery, he pushed the lines of representation about as far as they could go with his luminous swaths of color, a technique that would come to define Color Field painting. By the early 1960s, the cycle of mutual inspiration between Avery and the younger generation of Color Field painters came full circle, visible in a comparison between Avery’s work of this period, exemplified by Mountain and Meadow, and a watercolor by Paul Feeley, executed in Greece a few years later (Fig. 15). Feeley, who played a vital role in American post-painterly abstraction during the 1950s and 1960s as head of the visual arts department at Bennington College in Vermont, had largely purged representational elements from his art by the early 1950s. But in 1961 and 1962 he executed a series of landscape-based abstractions in Spain and Greece that parallel Avery’s balance between abstraction and representation in the same period. Feeley’s works almost certainly owe a great deal to his encounter with Avery’s art when Bennington College hosted a major retrospective of Avery’s work in 1960. The exhibition premiered at the Whitney Museum of American Art and was seen at sixteen other venues across the country.

By the end of his time in Vermont, Avery had established a major reputation in the American art world. His first solo museum show was held at the Phillips Collection in 1943, the same year he began to be represented by Paul Rosenberg, one of the most respected dealers of progressive painting in America. After a period of widespread recognition, by the late 1940s and into the 1950s, with the rise of “pure” abstraction, his work was out of favor. Following his own path, however, and never giving in to popular trends, by the late 1950s and into the 1960s, Avery was once again lauded as he pushed the boundaries between abstraction and observed reality. A close examination of his work as it relates to Vermont, both directly in the abundant oils, watercolors, prints, and drawings based on observation of the Green Mountain State’s landscape, and the relationship between his late paintings and Color Field painting, with its many deep ties to Bennington College, help us to better understand his rare contribution to the history of twentieth-century American painting.

Milton Avery’s Vermont is on view at the Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont, through November 6, 2016 and is accompanied by an 80-page, full color catalog with essays by Karen Wilkin and Jamie Franklin. For more information visit www.benningtonmuseum.org.

-----

Jamie Franklin is curator of the Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Antiques & FIne Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

.jpg)

1.jpg)