History, Labor, Life: The Prints of Jacob Lawrence

| |

Fig. 1: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Two Rebels, 1963. Lithograph on Rives paper from a plate hand-drawn by the artist, 30½ x 20⅛ inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), the artist most often recognized for The Migration of the Negro (later renamed The Migration Series), was just twenty-four years old when his magnum opus series of sixty paintings first garnered national acclaim in 1941. Perhaps less often cited but equally important, however, are the prints he created in the decades that followed. A new exhibition, History, Labor, Life: The Prints of Jacob Lawrence, will open at Sacramento’s Crocker Art Museum with more than ninety works from the artist’s printmaking career spanning 1963 to 2000.

Lawrence began printmaking following his first retrospective in 1960 at the Brooklyn Museum. Already an established painter, he embraced the opportunity to reach a wider audience by transitioning to a medium that was more accessible and readily available. Printmaking was particularly well-suited to his bold, graphic aesthetic, and he embraced the medium as an experimental avenue through which he could revisit and remake earlier paintings — a practice that began with his very first print, Two Rebels (1963) (Fig. 1).

Originally painted in the vivid, saturated hues typical of his work (Fig. 2), Lawrence created Two Rebels in response to the anti-segregation demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama. Early 1963 marked the launch of Project C (also known as The Birmingham Campaign), organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and led by members like Martin Luther King Jr. The campaign called for African Americans to confront racial segregation laws through acts of civil disobedience — acts that were ultimately met with violence and police brutality. The “rebels” in Lawrence’s painting and subsequent print represent the protesters who often faced mass arrest and whose persistence brought global attention to the severity of racial discrimination in the South.

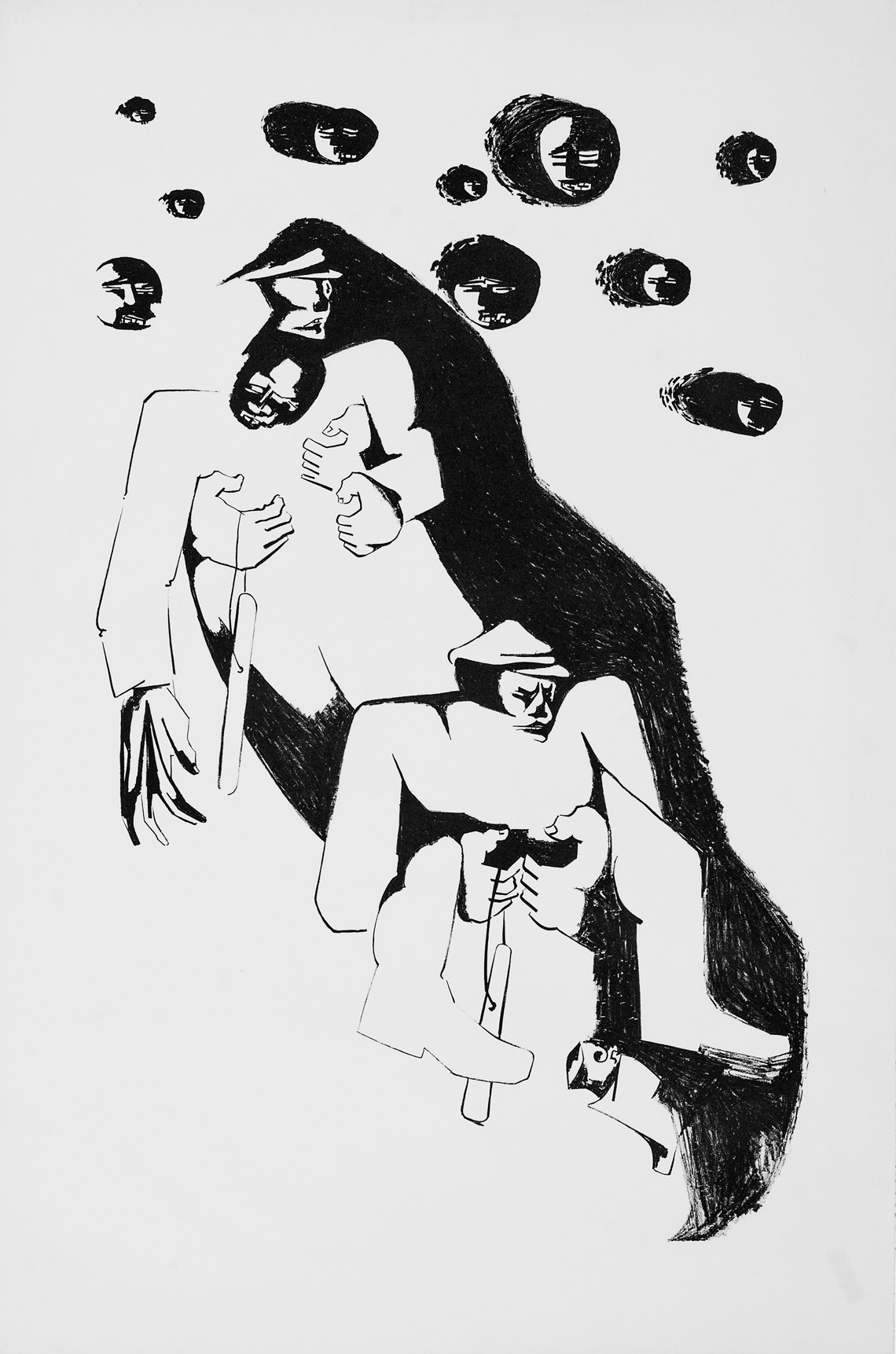

While there is a clear connection between the subject matter of the painting and print, the number of marked differences illustrate the creative freedom printmaking afforded the artist — and the degree to which he embraced it. The print retains the painting’s title, Two Rebels, yet it depicts only two officers and one “rebel.” Peter T. Nestbett, former director of the Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, observes: “The aggressive crayonlike markings and isolation of the figures in the open expanse of white paper contrast significantly with the painting’s more harmonious and integrated surface.” 1 Although it lacks the vibrant color of the painting, the print’s black-and-white palette strengthens its visual potency and emphasizes the tension among the subjects portrayed.

.jpg) |  | |

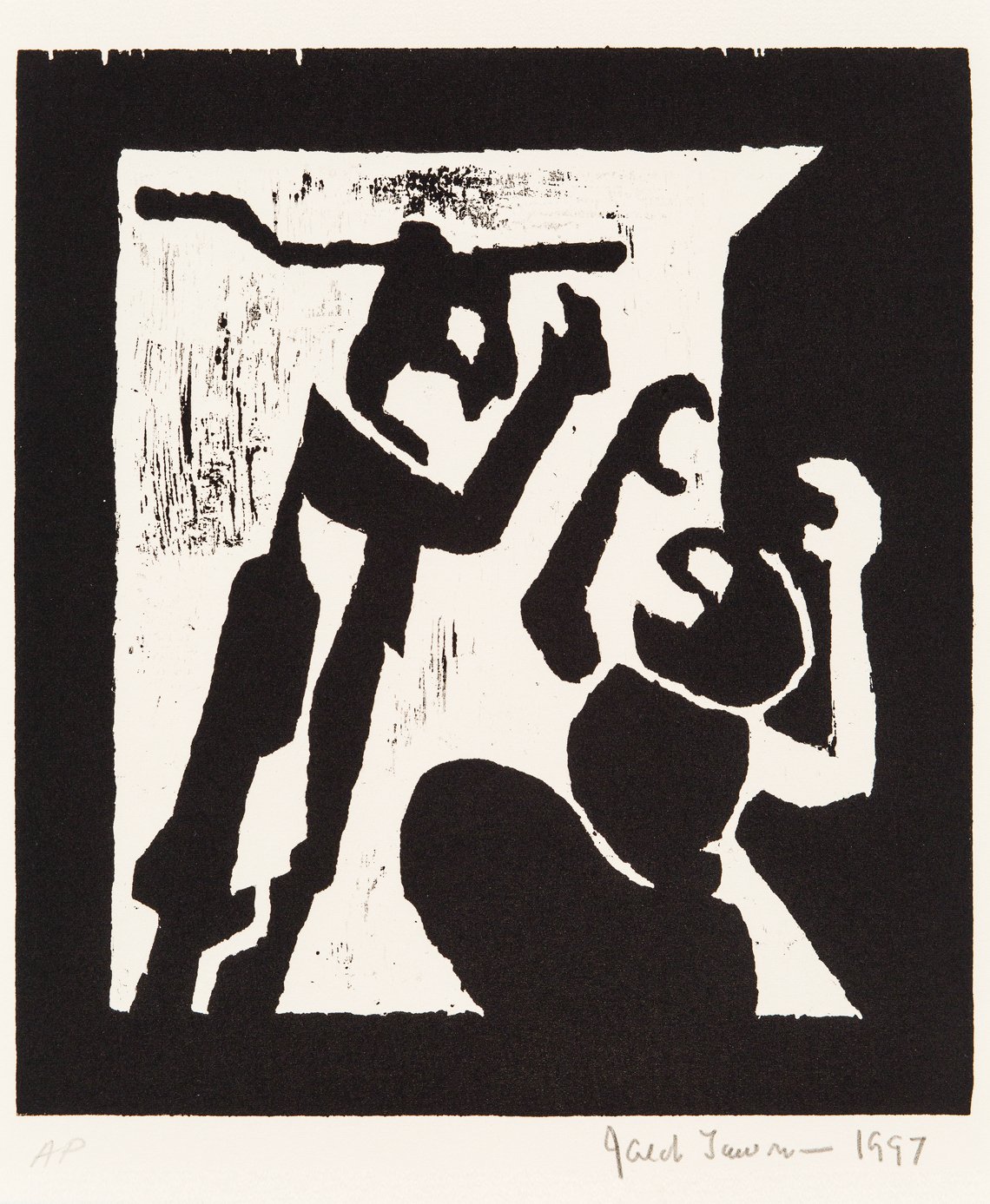

Left: Fig. 2: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Two Rebels, 1963. Egg tempera on hardboard, 23¼ x 19¼ inches. The Harmon and Harriet Kelley Foundation for the Arts. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. This work is not included in the exhibition. Right: Fig. 3: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), The Ant and the Grasshopper, 1997. Woodcut on Rives Light paper from a block hand-carved by the artist, 9⅞ x 8 inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. | ||

| |

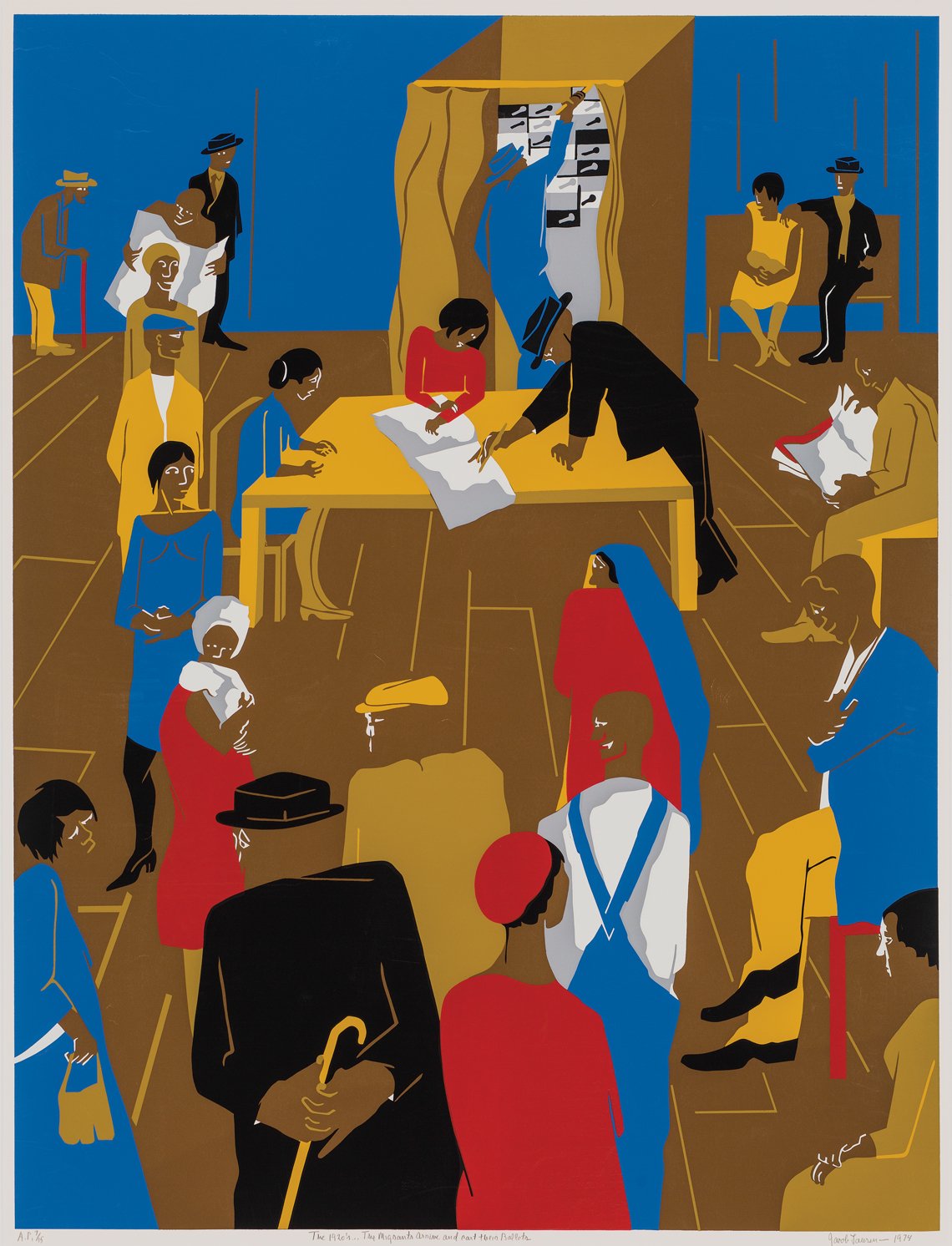

| Fig. 4: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), The 1920’s . . . The Migrants Arrive and Cast Their Ballots, 1974. Silkscreen on paper, 34½ x 26 inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

Printmaking also allowed Lawrence to experiment with a variety of media and techniques, including drypoint, etching, silkscreen, and woodcut (Fig. 3). The exhibition offers viewers a firsthand look at the subtle details and range of textures produced over the course of the artist’s printmaking ventures that are often lost in photographic reproductions. These range from energetic lines, like those in Two Rebels, to concise, stenciled, geometric figures, like those in The 1920’s . . . The Migrants Arrive and Cast Their Ballots (Fig. 4). Whereas the former example echoes the chaos, violence, and emotional turbulence of the scene portrayed in its approach, the latter emphasizes the flattened picture plane and Cubist elements that marked his style.

Regardless of the technique explored, storytelling remained central to Lawrence’s work. As its title suggests, History, Labor, Life is organized thematically, focusing on the narrative aspect of the artist’s work instead of tracing his technical progression. Three major categories — history, labor, and life — accommodate the breadth of subject matter he portrayed and include African American and African diaspora histories (Figs 5, 6), as well as scenes of everyday life and the artist’s memories of growing up in Harlem.

|  | |

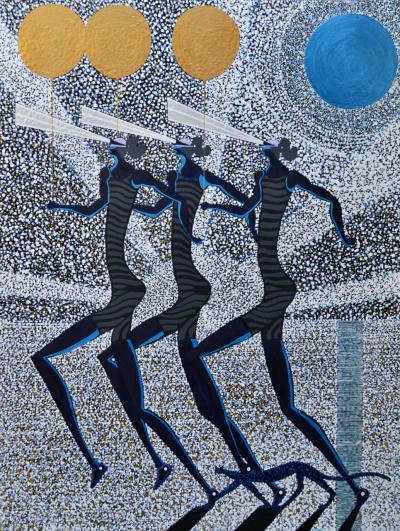

Left: Fig. 5: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Olympic Games, 1971. Screen print on paper, 42½ x 27½ inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right: Fig. 6: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Revolt on the Amistad, 1989. Silkscreen on paper, 40⅛ x 32⅛ inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. | ||

| .jpg) | |

Left: Fig. 7: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Schomburg Library, 1987. Lithograph on paper, 33¼ x 23½ inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Right Fig. 8: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), The Builders (Family), 1974. Silkscreen on paper, 34 x 25¾ inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. | ||

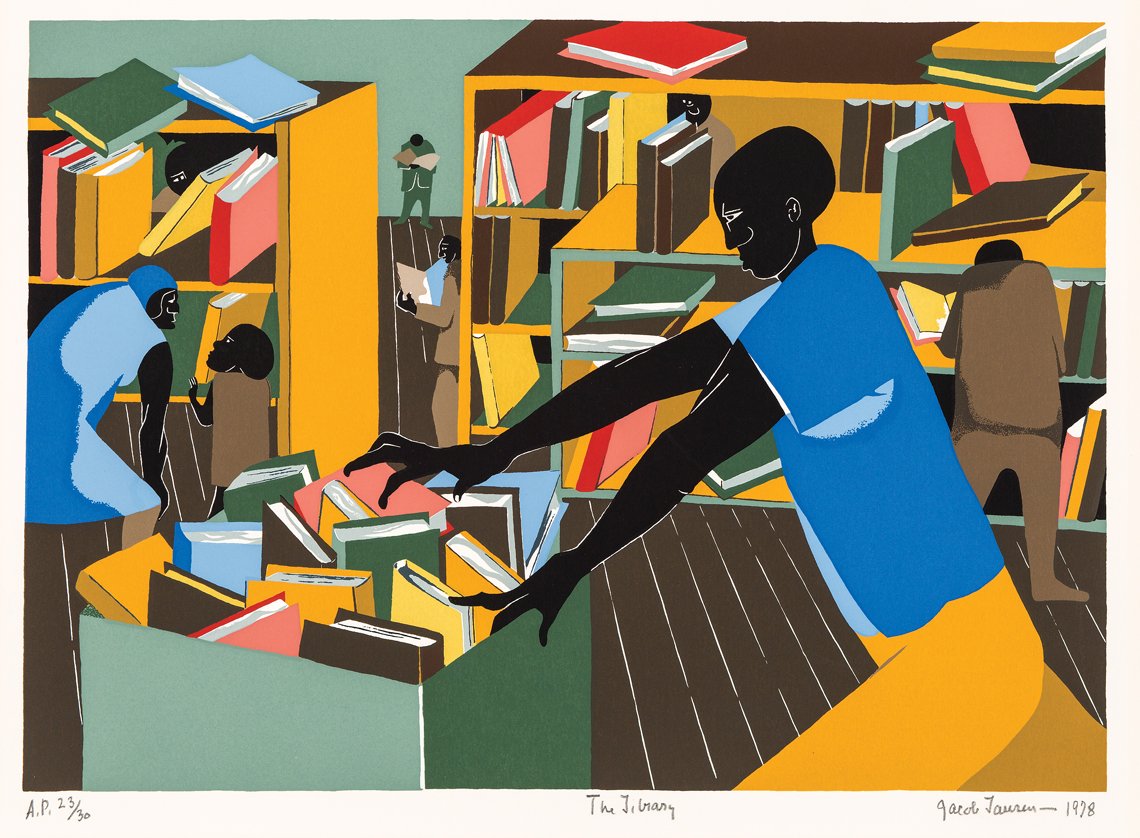

Regular visits to the library, for instance, were a major part of Lawrence’s life from a young age. “I was encouraged by my teachers to go to the library, all of us were…and it became a living experience for us,” he recalled of his childhood. “I would hear stories from librarians about various heroes and heroines. The library in my day was a very important part of my life.” 2 The Schomburg Branch of the New York Public Library (today, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture) was particularly important to the artist’s career, as it was where he conducted research for The Migration of the Negro. Although Schomburg Library and The Library (Figs. 7, 9) allude to everyday activity, the prints appear alongside his renderings of builders and construction (Figs. 8, 10) in the “labor” section of the exhibition. The exhibition’s broad, overarching categories encourage visitors to consider each theme in its many forms; labor, for instance, encompasses manual labor as well as intellectual labor and the artistic process.

|

Fig. 9: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), The Library, 1978. Silkscreen on paper, 20¼ x 24 inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

| |

Fig. 10: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Stained Glass Windows, 2000. Silkscreen on paper, 32 x 25 inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

At Schomburg Library, Lawrence also read about many of the figures portrayed in his historically themed works — Harriet Tubman, John Brown, and Toussaint L’Ouverture, among them. The exhibition includes examples of the artist’s complete print portfolios that depict a narrative over multiple scenes, often with accompanying text. The Legend of John Brown recounts the story of the American abolitionist in twenty-two prints; Toussaint L’Ouverture illustrates the story of the former slave who led the Haitian Revolution in a series of fifteen scenes.

Elsewhere, as in Forward Together (Fig. 11), related to his earlier etching Forest Creatures (Fig 12), Lawrence compresses narrative into a single scene. Originally created as the painting Through Forest, Through Rivers, Up Mountains (in the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Collection, Washington, D.C.), one of many illustrations for the 1967 children’s book Harriet and the Promised Land, it portrays American hero Harriet Tubman. As a major “conductor” of the Underground Railroad, Tubman helped hundreds of fugitive slaves escape north to freedom. In the print, she stands in a bright red cloak, her arms extended as though directing an orchestra. Her left hand reaches for the emerging figures, the ends of her outstretched fingers curled as though pulling them toward her. She points to the horizon with her right arm, ushering the runaways in the direction of the North Star.

|

Fig. 11: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Forward Together, 1997. Silkscreen on paper, 25½ x 40⅛ inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

| |

Fig. 12: Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), Forest Creatures, 1969. Etching and drypoint on wove paper, 18¾ x 22¼ inches. © 2018 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. |

History, Labor, Life: The Prints of Jacob Lawrence encourages visitors to engage with the narrative quality of the artist’s work, and to appreciate the dynamic interconnections between the themes and stories he portrayed. Just as the relationship between his painting and printmaking were intertwined throughout his career, so too were his portrayals of the past and present, creating compelling narratives with which we continue to engage.

History, Labor, Life: The Prints of Jacob Lawrence, curated by Storm Janse van Rensburg, Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) Museum of Art, will be on view at the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, Calif., from January 27, 2019, through April 7, 2019. The exhibition will travel to the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Alabama (August 3–October 27, 2019), and the Lowe Art Museum at University of Miami, Florida (March 5–June 7, 2020). For more information, visit crockerart.org or call (916) 808-7000. This exhibition is organized by the SCAD Museum of Art and is made possible with support from the Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation. The Complete Jacob Lawrence boxed set includes Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence and Jacob Lawrence: Paintings, Drawings, and Murals (1935–1999), edited by Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois (University of Washington Press, 2000). For more information, contact the Crocker Art Museum Store, (916) 808-5531.

Christie Hajela is assistant curator at the Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, California.

This article was originally published in the 2019 Anniversary/Spring issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com.

1. Peter T. Nesbett, “Introduction: Jacob Lawrence: From Paintings to Prints,” in Jacob Lawrence: The Complete Prints (1963–2000), A Catalogue Raisonné, 2nd ed. (Seattle: Francis Seders Gallery Ltd., 2001), 9.

2. Jacob Lawrence, in a lecture at Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle, August 12, 1993. Quoted in Jacob Lawrence: The Complete Prints (1963–2000), A Catalogue Raisonné, 2nd. ed. (Seattle: Francis Seders Gallery Ltd., 2001), 41.