Homer, Sargent, and the American Watercolor Movement

The phenomenal rise in the popularity of watercolor painting in the United States that followed the formation of the American Watercolor Society in 1866 drew energy from a new talent bank of artists and an expanding class of collectors, on the rise after the Civil War. Determined to overturn the prejudice against watercolor as a medium for amateurs and commercial artists, the members of the new society recruited support from all corners of the art world. Beginning with respected Hudson River School landscapists, they also gathered previously marginalized artists, including Ruskinian reformers, illustrators, designers, young progressives returning from Europe, and women artists seeking a professional foothold. The annual watercolor exhibitions, held in the galleries of the National Academy of Design in New York beginning in 1867, became an arena where fresh, unknown painters—such as Thomas Eakins and Edwin Austin Abbey—could win laurels, and older artists, including Winslow Homer, could refashion their reputations. The liberality of the watercolor jury created an exciting and eclectic display, with shocking “impressionist” sketches jostling for attention alongside the polished work of old-fashioned realists, and the paintings of venerable academicians side by side with architectural elevations and flower pieces by obscure beginners. Eakins, Abbey, and Homer all sent in work for the first time in 1874 as the new society began to catch on with artists, critics, and collectors; by 1882 there were few painters in New York who were not working in watercolor.

This enthusiasm for the new medium created a new market, and a set of new stars, particularly Homer, who tested his audience with a series of startling changes in style and subject matter that reflected the shifting tastes of the watercolor movement between 1874 and 1882. By the mid-1880s, Homer was recognized as the leader of the American school in watercolor, and by the 1890s his exhilarating hunting and fishing subjects in the medium had won widespread admiration and a steady clientele. His death in 1910 was followed by a series of tribute exhibitions and publications that celebrated his watercolors as both personal and national triumphs.

Just as Homer was canonized, the much younger John Singer Sargent began to exhibit his watercolors for the first time. Like Homer, he had used the medium from childhood, but Sargent preferred to keep his watercolors private until 1904, when he sent several to an exhibition in London. A much larger solo show of watercolors in 1905 was followed in 1909 by a landmark New York exhibition that was purchased in one fell swoop by the Brooklyn Museum. A frenzy of competitive collecting by American museums and patrons ensued, demonstrating Sargent’s entrancing appeal in the medium as well as the by-now-established fondness for watercolor all across the United States. By the time of Sargent’s death in 1925, the medium was a favorite of the next generation, including a diverse parade of young moderns such as Charles Burchfield, Charles Demuth, Edward Hopper, and John Marin, who all learned watercolor from early experience in illustration or design. The arc of this watercolor story, from the neglected status of the 1860s to the wide-ranging practice of the 1920s, was told in the exhibition and catalogue, American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent, which was on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from March 1-May 14, 2017.

Winslow Homer rode the watercolor movement from its beginnings to its crescendo of popularity, by turns shaping and shaped by the rising interest in the medium. His first sessions of experimental painting in watercolors in 1873 grew out of long practice as an illustrator, using ink and gouache daily, to compose an image for reproduction. His work painted during this summer in Gloucester was different, however, in its bold handling, bright color, and absence of finish. Broad strokes of opaque watercolor and loose, wet passages in the clouds demonstrate a breezy technique paralleling the work of the French Impressionists, who were undertaking similar carefree resort subjects at this same moment. While progressive critics exclaimed over the freshness and originality of these watercolors, conservative viewers were puzzled by the audacity of an artist submitting mere sketches to an exhibition. In fact, the watercolor society’s exhibitions welcomed such material as part of the long tradition of outdoor work in the medium.

The Boston painter J. Frank Currier burst onto the watercolor scene in 1879, when his wild views of the countryside near Munich stirred up controversy in New York. Painted on soaked paper, which allowed the washes to run and blur, his landscapes were identified as “impressionist,” although they had little to do with the work of the Parisian independents in the circle of Monet. To Americans, this new style came from the expressionist handling and light-and-dark palette of Currier and the Munich painters, the wet techniques of the Dutch Barbizon school, the simplicity and suggestiveness of Whistler, and the flashing bravura favored by the circle of the Spanish painter in Rome, Mariano Fortuny. American artists confronted this avant garde at the watercolor exhibitions, where examples of the new painting were set against the more conventional, British-based painting of the mainstream. Homer took note of this shocking new work; his second round of Gloucester watercolors, painted in 1880, recovered the broad style of his earlier sketches. The critics, once confused by his sketchiness, now accepted his work as “impressionism.”

Homer left New York in 1881 to spend a year and a half in a fishing village on the north coast of England. He returned late in 1882 with a revolutionized style. Last seen at the watercolor exhibitions with sketchy marine scenes and charming shepherdess subjects, he now showed an array of heroic figure compositions, masterfully painted in a traditional English watercolor style. Initially shocked by the change, critics were won over by the majestic work exhibited in 1883, including the monumental Inside the Bar, with its theme of human fortitude in the face of nature. With such work, Homer reasserted his place at the head of the American watercolor school, but now in alliance with the Victorian mainstream rather than the Impressionist avant-garde.

Homer’s younger friend, Edwin A. Abbey, was also raised in pen-and-ink illustration and watercolor; he did not paint in oils until he was forty. The watercolor exhibitions gave Abbey a chance to prove himself as a “fine artist,” capable of producing large, elaborate compositions that rivalled the impact of oils. Abbey’s masterpiece, An Old Song, showcased his brilliant technique, which embraced a wide repertory of effects, from broad washes to fine detail. It also demonstrated his historical genius, able to imagine and construct a rich, tender narrative from the past to beguile audiences grown uneasy by the pace of modern change. Inviting the viewer to tour a late-eighteenth-century English interior, Abbey tells the story of a young woman whose song conjures up an even deeper past for an older generation lost in reverie. With such exhibition pieces, Abbey joined Homer—whose new English work was similar in ambition and complexity—at the head of the American watercolor school.

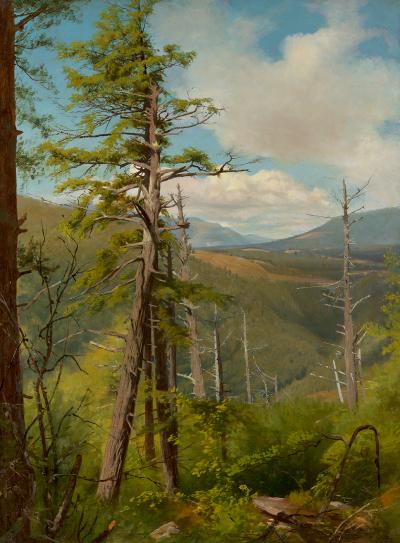

Homer had vacationed in the Adirondacks of New York state as a young man, but he rediscovered this landscape in 1889 and found new levels of artistic achievement in the next decade, depicting woodland subjects. A passionate fisherman himself, he understood the charms of the sport and the therapeutic beauty of the wilderness. Among his admirers, anglers enjoyed the reverie of a quiet mountain lake and a moment of victory, deftly drawn, while connoisseurs gasped over his virtuoso effects in watercolor, such as the quickly scraped arc of the fishing line. With an appeal based on aspects of American national identity, Homer’s watercolors celebrated individualism, the power of the landscape, and the ideal of oneness with nature.

-

Winslow Homer (1836–1910), After the Hurricane, Bahamas, 1899. Watercolor, with touches of opaque watercolor, rewetting, blotting, and scraping, over graphite, on moderately thick, moderately textured wove paper, 14-15/16 x 21-3/8 inches. The Art Institute of Chicago; Mr. and Mrs. Martin A. Ryerson Collection (1933.1235).

Homer’s first visit to Bermuda and Cuba in 1885 launched a series of trips to the Caribbean over the next two decades that would inspire some of his most memorable watercolors. The beautiful bodies of the sponge divers and fishermen of the Bahamas and Key West appear regularly in his work, their gleaming skin set against the blue of the sea and the sky. His masterpiece, After the Hurricane, tells the dark side of their story. Is the huddled figure alive or dead? Mere debris, like the battered boat, humans have no privilege in the face of a storm. Homer matched the sober meditation of his subject with virtuoso handling, showing delicacy in the modeling of the figure and breadth in the sky and water.

Just as Homer painted Diamond Shoal, Sargent emerged as a new star of watercolor. Raised in Italy by his Philadelphia-born parents, he learned the medium while touring Europe as a boy. Keeping his watercolors for his own pleasure, he rarely exhibited them until 1904, when he sent four—including Gondoliers’ Siesta—to the annual exhibition of the Royal Watercolor Society in London. Knowing Venice well, he enjoyed finding fresh viewpoints to make its familiar monuments surprising. This seemingly casual glance at the Grand Canal was probably painted from a gondola, face to face with two sleepy gondoliers. The informal mood is deceptive, however, as Sargent carefully planned this subject with a graphite underdrawing, reinforced at the last with fine pen rulings that trace the carefully plotted perspective of the architecture. The warm reception of these watercolors inspired a much larger exhibition of his work in London in 1905 that established the fame of his work on both sides of the Atlantic. Gondoliers Siesta was among the first of his watercolors seen in the United States: given by the artist to his aunt, it was carried home to Philadelphia in 1905 and immediately lent to the Philadelphia Water Color Club’s exhibition of 1906.

Sargent’s annual trips to the mountains in the summer were binges of watercolor painting. Released from the pressure of his portrait and mural commissions, he took pleasure in the pursuit of impressionist subjects that happily evaded narrative and detail. A group of friends napping on a hillside became a study in light, color, and interlocking shapes. As they sleep, the artist is restlessly moving, creating a sense of flickering light, scattered color, and sensuous abandon. The provocative tangle of bodies seems chaotic and natural, but it has been artfully organized. Equally strategic is the white shape of the parasol, expertly reserved from clean paper and set against a wet and blurry background evoking the dreamy situation.

This dynamic image, which may have been Homer’s last watercolor, was painted as the artist neared the age of seventy. After thirty years of exhibition work in the medium, he was by this time a consummate master. His memory of a recent voyage along the coast of North Carolina depicts a crew frantically shortening sail in the face of a squall, with a distant view of the lightship anchored off Cape Hatteras to warn ships away from the shoals. As if suspended in the waves as the schooner surges toward us, Homer imagines a thrilling viewpoint that captures the desperate activity, the mixed light before the storm, and the weight and translucency of the sea.

Homer’s visit to Key West, Florida, in 1903 produced a brilliant new series recording the dazzling light and turquoise water of the tropics. Dropping clean water into his washes to make them lighten and blur, he continued to simplify his palette, relying on only three colors—blue, burnt sienna, and his familiar vermilion—added to black, which settles out in grainy washes suggesting shadow and cloud. Expertly, he reserved zones of white paper to read as the sails and the hull of the Lizzie.

Sargent came to Boston on several occasions to work on major mural commissions; in 1917, his stay was extended by the danger to transatlantic shipping posed by World War I. His usual travels to the Mediterranean were replaced by a trip to Florida, where he visited the grand estate Vizcaya, still under construction by his friend James Deering. With the gleaming palazzo in the distance, he painted a group of relaxed young men, probably workers on the estate. He arranged them in casual postures (like those of his friends on the Alpine hillside), surprisingly foreshortened and immediate, with a similar suggestion of sensuous pleasure. Sargent evoked heat, light, and moisture in the look of dappled sunlight through foliage and the feel of shallow water washing across the legs of the man at the right, deftly suggested by dragged strokes of opaque pigment.

Like Homer, Sargent responded to white sails and hulls in a sunny harbor, here on the island of Mallorca, off the coast of Spain. Despite the tranquil subject, Sargent’s effect is one of high energy by contrast to Homer’s similar harbor view from five years earlier, Fishing Boats, Key West. Simpler, calmer, broader, and more economical in his handling, Homer is plain and direct where Sargent is animated, effusive, and subtle. Typically, figures play no part in Sargent’s view, while Homer adds a note of narrative in his shouting, waving sailors.

On breaks from a portrait commission in Florida, Sargent trolled for watercolor subjects. He complained that “palmettos and alligators don’t make interesting pictures,” but his results proved the contrary. As with his dozing friends on the mountainside, or the bathing workmen at Vizcaya, he enjoyed creating a tangle of bodies that merge in the sunlight; here, a group of mud-encrusted alligators that leer menacingly at the artist. The delicate pattern of light and shade required careful drawing and a patient technique to create its effect of immediacy. As with most of Sargent’s watercolors, the illusion melts away at close range, as ominous monsters become a beautiful field of blue, lavender, and gold. Along with The Bathers, this watercolor was among a portfolio of eleven of Sargent’s Florida subjects swept up by the Worcester Art Museum from Sargent’s exhibition of his work in Boston later that spring.

The art of watercolor turned a page with Maurice Prendergast, whose work departed from the pleinairism of impressionism with more deliberation and consistency, moving into a fresh, original style in watercolor. After returning from study in Paris to settle in Boston as a graphic designer, Prendergast spent free time painting watercolors depicting holiday crowds at local parks and beaches. A trip to Italy in 1899–1900, however, turned his career around. In front of Saint Mark’s church in Venice he was delighted by the reflections in the puddles left after a shower. Alive with light, color, and a sense of bustling tourists, he portrays the dignified, symmetrical façade of Saint Marco skewed by the diagonal pattern of the paving, broken by erratic puddles and disconcertingly giant flags. Though capturing a moment in time, this picture was probably painted slowly, indoors, from memory, using notebook sketches and a postcard of the church. When his Italian watercolors were shown in Boston and New York, his reputation as an innovative post-Impressionist was confirmed and he met a new set of friends, who gathered Prendergast into the progressive group that would become “The Eight.”

Visiting Paris in 1907 and again in 1909–10, Prendergast embraced the newest art, particularly the watercolors of Paul Cézanne. Bridging the world of Winslow Homer and John Singer Sargent (whose work he admired) and these new sources of inspiration from France, Prendergast pushed the art of watercolor into the modern era and linked together the first watercolor movement and the new generation. Prendergast revisited the beach subjects and processional compositions of his earlier work, now with larger, simpler figures, pressed forward into a shallower space. Flat color patches and strong contours, sometimes overlaid with pastel, built an assertively modern, decorative surface. In a similar spirit, the next generation of modernists would find watercolor a familiar field for experimentation. By the time of Prendergast’s death in 1924, closely followed by Sargent’s death in 1925, many young American painters—including the great modernists of the Stieglitz circle, John Marin and Charles Demuth—were accomplished and celebrated in the medium, and others, such as Edward Hopper and Charles Burchfield, were entering the scene. Watercolor was now embraced as perfectly suited to the national artistic character.

Kathleen A. Foster is the Robert L. McNeil, Jr., Senior Curator of American Art, and Director, Center for American Art, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine.

To read “John Singer Sargent and His American Contemporaries in Venice,” click here.

To read “An Artful Life: The Baker/Pisano Collection of Late 19th-Century American Art,” click here.

To read “An Influencer in the Arts: The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts,” click here.

,-1904-5_.jpg)