In the Land of Sunshine: Modern Art of the California Coast

In 1850, shortly after California officially became part of the United States, professional artists began to travel along the coastline of the Golden State seeking out engaging subject matter for their paintings. Early works often captured scenes of San Francisco Bay where ships docked and large numbers of people unloaded to stake claims in the California Gold Rush. Within a few years artists were regularly heading south to other coastline settlements like Monterey, Santa Cruz, Santa Barbara, San Pedro, and San Diego. Many new towns and villages have sprung up along the shores of the Pacific Ocean since 1900, and some of them, like La Jolla, Laguna Beach and Carmel became well known artist communities. Those artists produced paintings depicting the people and the character of their local geography as both grew from the twentieth into the twenty-first century.

In these coastal towns, an array of cultures emerged. Fishermen from all over the world came to the areas near Monterey and San Pedro, where they built up the fishing and canning industries. The lumber industry drew loggers into the Santa Cruz area, and oil workers came to Venice Beach, Long Beach, and Huntington Beach when oil was discovered locally. Towns along the coast evolved with different identities directly associated with the businesses and cultural influences that were present. An unusually high number of sub-cultures also developed in the coastal communities. Beach sports were prominent with sailing, surfing, fishing, diving and volleyball becoming more and more popular.

In the Land of Sunshine: Imaging the California Coast Culture, at the Pasadena Museum of California Art, brings together paintings, fine art prints, and ephemera that capture these changes over the past 166 years. The works are not only engaging as art, but serve as a visual documentation of the California coastline development since the state was formed. Images range from sublime coastline scenes to views of the Los Angeles Airport in El Segundo and an oil refinery in Wilmington. The California Surf Culture is well represented since most of the works were painted by artists who also surfed. Painting styles range from nineteenth-century representational works by European-trained artists to abstract works by modernists. Specific stylistic approaches include luminism, , cubism, surrealism, impressionism, abstract surrealism, photo realism, American illustration, and California style watercolors.

Throughout his sixty-year career as a professional artist, Phil Dike’s stated goal was to use various forms of abstraction to visually capture the excitement he derived from viewing scenes from California life. He never totally abandoned recognizable subject matter, but usually distorted objects, changed their colors, and created abstract shapes and symbols to represent wind, motion, and sounds. Not particularly interested in selling his art, at various times he was represented by art galleries in New York City, Los Angeles, and Laguna Beach. He preferred to work at his own pace with no pressure from outside influences. Dike taught painting at the Chouinard Art School, Scripps College, Claremont Graduate School, and at the Brandt Dike School in Corona del Mar. Roger Kuntz, Robert Frame, Robert E. Wood, and John Severson, all represented in the exhibition, were influenced to some degree by Dike’s ideas and teaching.

From childhood, Dike spent time in and around Newport Beach. His family vacationed on the sand banks of Balboa Bay, from where he could access the seaside activities of sailing, diving, swimming, fishing, shell hunting, and sand castle building. The commercial fish cannery and boat building operations were within walking distance. Dike often stated that one of his favorite places to view the Pacific Ocean was from the bluff in Corona del Mar, just above Pirates Cove. From there he could see people relaxing on the beach, fishermen rock fishing, and sailboats coming in and out of the harbor mouth, made more magical in the evening as the sun set behind Catalina Island. Painted in the late 1940s, Sunlit Afternoon was inspired by an afternoon spent at that location. It is an engaging abstract interpretation of an easily recognizable Southern California coastline scene. Several other Dike works from that area and time are also in the exhibition.

The unusual coastline rock formations in the La Jolla area have been attracting artists since about 1900. At that time, San Diego was adjusting to an influx of people during the Southern California land boom of the late 1800s. Some of those new residents were artists who often traveled the fifteen miles north to the village being developed near La Jolla Cove. Alson Clark, a world traveled professional artist, settled in Southern California after serving in World War I. He developed a reputation in the Los Angeles region as an important fine artist and art instructor. In the late 1920s, he was included in a list of the twelve premier California artists of the era. In 1929, each of those artists agreed to have one of their paintings reproduced on the cover of Touring Topics, a monthly magazine published by the Automobile Club of Southern California.

Clark’s La Jolla was on the cover of the September issue. His impressionist style reflects his studies with American Impressionist William Merritt Chase. When Clark painted this picture, the first of many hotels had just been built in La Jolla and people from all over Southern California were vacationing there, drawn by its ideal climate, surf bathing, and magnificent sunset views.

During the California Gold Rush, San Francisco became the first large-scale city to be developed along the California coastline. By the 1880s, when Raymond D. Yelland painted this picture, there were over 233,000 people in the city, making it by far the most populated city in California. This work depicts a view of Golden Gate, the name given to the body of water between Land’s End on the San Francisco side and the Marin Headlands on the other. Angel Island, a small island in the middle of the San Francisco Bay, known as the “Ellis Island of the West,” was used as a station to process immigrants for many years. In the 1930s, the Golden Gate Bridge was built just beyond where the sailing ship appears in the distance in Yelland’s painting.

Yelland moved to California in the 1870s. He settled in the San Francisco area, where he became a professional artists and art teacher. Golden Gate from Angel Island was painted in a style that reflects his interest in luminism, the term used to describe a representational style inspired by the earlier Hudson River School works. As Yelland’s painting reveals, the luminist style was well suited to interpretations of the California landscape.

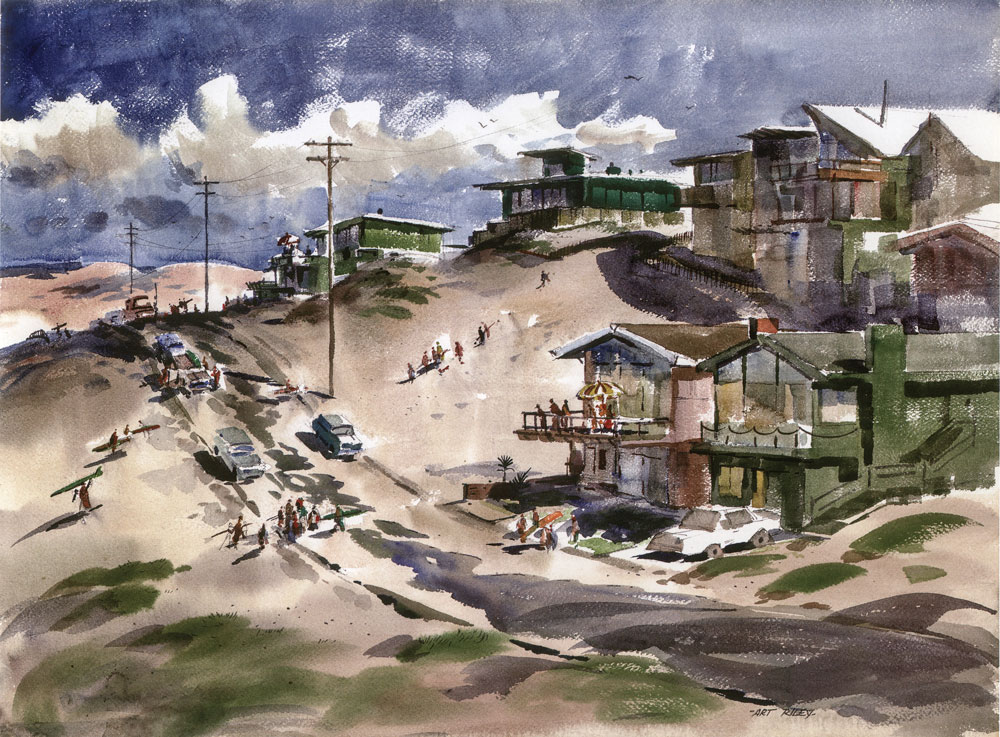

Between the 1930s and 1960s, Art Riley was a prominent member of the California Watercolor Society and an active member of the American Watercolor Society. Also known for his contributions to the California Style watercolor movement, he used transparent watercolors and developed a painting language that allowed him to paint quickly with spontaneous brushwork, yet with an amazing amount of control. This ability was largely due to the work he did at the Walt Disney Studios. There he produced animation art watercolor backgrounds for many of the most famous animated feature films of the mid-twentieth century. His film credits include Pinocchio, Fantasia, The Three Caballeros, Cinderella, and Peter Pan. His work on those animated feature films was carefully rendered and contained elements of fantasy.

The subject of Playa del Rey was a housing development on the sand next to the Los Angeles Airport. In the 1960s, the beach was a popular gathering spot for surfers and teenagers. In more recent years, residents were forced to move out of their homes and the housing community was torn down. The reasons given for this forced evacuation were concerns for residents’ safety and general health.

Riley lived in Burbank until the 1970s, but had a second home in Pacific Grove. After retirement he moved there and produced an extensive series of watercolors depicting the beaches, rocks, and the Pebble Beach golf course along the famous 17 Mile Drive, which ran right by his home.

In 1956, John Severson produced the first known series of paintings inspired by the developing Southern California youth surf culture. They are large-scale oil paintings, often painted on Masonite panels. Still finishing his college education at the time, the series was produced for his MFA graduate exhibition at Long Beach State College.

During the 1960s, Severson, a dedicated surfer, started Surfer Magazine, the first serial surf-related publication. Initially published to promote the surf movies he was making, it was so successful he made it a bi-monthly publication. Although he sold his interest in Surfer in 1970, it is still the world’s premier surf culture magazine. The early issues of this magazine were full of Severson’s drawings and graphic ideas. Severson reproduced his recently finished Surf Be Bop on the front cover of the 1963 February-March issue.

A big hit with surfers, it also received the 1963 Communication Arts publication award for best magazine cover of the year. Severson’s interest in BeBop and West Coast Jazz influenced his name for the work. He once said his inspiration for this painting was an impression of surfers sleeping on Huntington Beach after a long morning surf. He continues to produce drawings, watercolors, oil paintings and acrylic paintings that document the surf culture and from the surfer’s point of view.

Dennis Hare is among the Californian artists recognized as pioneers in the development of photorealism. Viewed from a distance, these works look like they were derived from photographs, but up close the best of these works look quite painterly, and on inspection, can be seen to have been worked on in creative ways. After achieving fame as a beach volleyball player in the the 1970s, Hare focused on an art career. His earliest exhibited works were photorealism watercolors. The Cove, an example of the work he produced in the first years of his professional art career, was inspired by a photograph he took on the beach at Monterey in Northern California. While it is easy to discern its photographic source, up close the painted strokes are obvious and the edges are blended and soft. Hare next became interested in oil painting and gradually developed his own individual abstract approach. At first, what he did was often viewed as an extension of the San Francisco abstract figurative movement of the 1960s, but his best works transcend that comparison. One of these abstract works is also included in the exhibition, and shows how this artist interpreted the California coast culture using two very different styles of art.

Donna Schuster settled in Los Angeles after studying with Frank W. Benson and William Merritt Chase. She arrived in 1913, just as Los Angeles was celebrating the opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct that provided the city and surrounding area with a steady supply of fresh water. By 1915, Schuster was a member of the California Art Club and was exhibiting in group exhibitions. Her works often featured figurative subject matter. When Schuster painted On the Beach, Malibu, she had apparently acquired access to the stretch of coastline between Santa Monica and Point Mugu known as Malibu.

Until the mid-1920s that particular section of California coastline was privately owned by the Rindge Family and they did not welcome many guests. If access was granted, most visitors rode into the area on horses because of the primitive paths. On The Beach, Malibu shows us what that area was like prior to Pacific Coast Highway days. It also provides a glimpse into how a talented artist took what she learned from Frank W. Benson and applied it to the Southern California beach culture that was beginning to develop when this work was painted.

Considering the fact that many thousands of people visited beaches in California prior to 1940, there are relatively few known paintings depicting people on the beach before then. When artists did choose figurative seaside subject matter, people were usually painted quite small and without enough detail to be identified. An exception was California representational artist Joseph Duncan Gleason, a gifted figure painter who produced works with clearly identifiable people at the beach. In the 1930s, Gleason sketched and painted works inspired by the California coast culture. By the mid-twentieth century he had also become well known for his yachting scenes and historical maritime subject matter featuring famous ships that sailed off the coast of California. He lived in Los Angeles, next to Griffith Park, but spent a great deal of time in Laguna Beach, where his mother-in-law, Lillian Ferguson, had a seaside home and an art studio. An avid sailor, he spent time at Newport Beach and San Pedro.

He and his wife Dorothy had two daughters, Eleanor and Lillian. When they were youngsters, Gleason often depicted his daughters and their friends playing along the seashore. Youthful Mariners was reproduced as a color print by a Swiss publishing company and distributed in Europe and America. Seven oil paintings by him are featured in the exhibition, along with a book he wrote and illustrated titled The Islands and Ports of California.

Roger Kuntz spent time as a child living near the beaches in San Diego County. In the post–World War II era, he attended art school in Claremont, where he received a well-rounded art education from teachers like Henry Lee McFee and Millard Sheets. After art school, Kuntz moved to Laguna Beach, where he became a well-respected artist and leading figure in that coastline art community. His art was sold locally and also handled by highly regarded art dealers and galleries in Los Angeles. He also exhibited in many annual museum exhibitions both in California and other states. Kuntz would often select a theme or subject matter and then produce a series of works.

During a particularly productive period, Kuntz was living at Crystal Cove, a small community in a protected cove just north of Laguna Beach. The homes are relatively primitive beach houses, built right on the sand and hillside, and are just enough inland to escape the high tide. While living there, he painted works referred to as The Girl Against the Light series. Interior With Figure is from that series and reflects his interest in abstract figurative painting. The house was one Kuntz rented and lived in during the mid-1960s.

The exhibition is named after Land of Sunshine, one of the first magazines dedicated to the promotion of Southern California. It is a tribute to the magazine’s editor, Charles Lummis, who worked tirelessly to create interest in Southwestern history and hired talented California artists to produce art for reproduction in his publication. His pioneering spirit was matched by his love for the California coastline.

In the Land of Sunshine: Imaging the California Coast Culture is on view through February 19, 2017 at the Pasadena Museum of California Art. For more information call 626.568.3665 or visit www.pmcaonline.org.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

-----

Gordon T. McClelland is an author and art exhibition curator who resides in Southern California.