Is it this Way or that Way?

The Carew-Way Connection

As noted in the previous article by Brian Ehrlich, Mary (1769–1833) and Betsy (1771–1825) Way were skilled artists working in New London, Connecticut. Painters of miniatures on ivory, the sisters also created charming “dressed” miniatures, a manner of depiction in miniature portraits seemingly unique to this pair. The question of where the sisters learned to create the charming dressed miniatures may remain a mystery. However, late-eighteenth-century newspaper advertisements and two silk embroidered pictures featuring dressed figures attributed to the school of Lucy Perkins Carew in nearby Norwich, Connecticut, may suggest an answer.

The Way sisters came of age during a time when young ladies of the middle and upper classes were expected to become proficient in the “polite accomplishments.” These talents were acquired by attending a female academy or taking lessons from a variety of independent teachers who specialized in subjects such as needlework, painting, singing, French, dancing, etc. No such schools are known to have advertised in New London at the time, but there were well known schools in neighboring Norwich. In fact, the output of girls trained in Norwich represents some of the most skilled and graphic needlework of the period, though very few of their teachers are identified. Newspaper advertisements from the area are quite specific as to the type of needlework and other disciplines offered. Instructress Lucy Perkins Carew first advertised in the Norwich Packet on April 3, 1798, offering to “board young misses” and teach them “English grammar, history, etc.,” and also “Drawing, Painting, Tambour, Embroidery, and all kinds of Needle Work.” 1 But, it is the advertisement of the following year, April 3, 1799, that is of the most interest. Here she again states that “she proposes to open a school at her house,” where the young misses will be “taught Cloath and Tiffina work on Sattin, with common embroidery, Tambour, and all kinds of Needle-work on Muflin [muslin]; with drawing, Painting, and Figure.” 2 Though applying fabric to miniatures and figures had been worked in England since the latter eighteenth century, no other school advertisements in Connecticut at any time mention “Cloath and Tiffina work on Sattin,” the technique in which fabrics were applied to create “dressed miniatures.”

Could Mary and Betsy Way have been taught by Lucy Carew? In 1798, Mary and Betsy Way were aged 29 and 27, respectively, and not likely candidates for a boarding school. But it is possible that their paths crossed, perhaps in the late 1780s, when the sisters were teenagers, as it is doubtful that Lucy would have started a boarding school with no previous teaching experience. We know that Mary and Betsy took singing lessons as teenagers (See Ehrlich; probably referenced because it was unusual), and, despite what is stated in Mary’s obituary—that she “was entirely self-taught” 3—it would be unlikely that singing was the only accomplishment the sisters pursued, especially in view of the fact they took up painting as a livelihood. (As hypothesized in Ehrlich’s preceding article, the obituary reference to lack of instruction likely refers to Mary having no formal training from an academic artist when in Connecticut.) Was Lucy Carew their sewing or painting instructor?

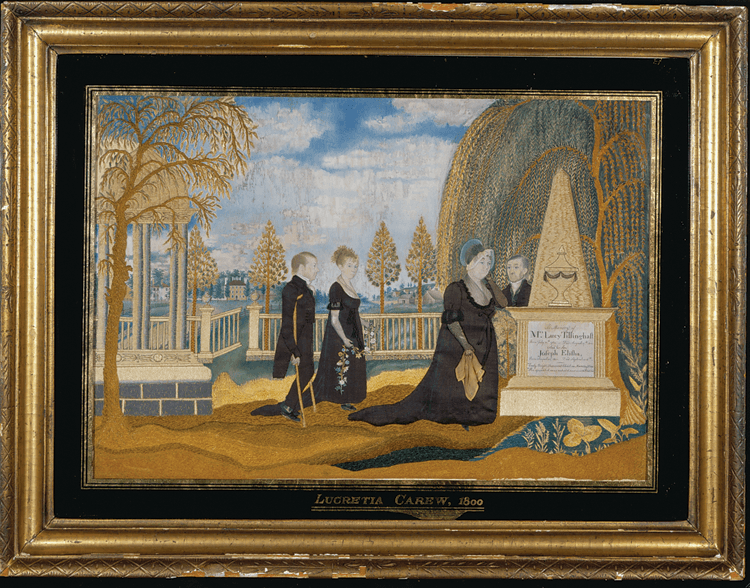

- Fig. 1: Silk embroidered and painted memorial by Lucretia Carew, 1800. Inscribed, “In Memory of/ Mrs. Lucy Tillinghast; Born July 11,th 1783—Died August 27,th 1800./ And her Son/ Joseph Elisha,/ Born August 23,/d 1800, Died September 6th/ Early, Bright, Transient, Chast, as Morning Dew/ she sparkled, was exhal’d, and went to Heaven.” Silk thread, applied fabric, paint and ink on silk, 20½ x 26¼ inches. Courtesy, The Museum at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, New York (00.1704). The figures represent Daniel and Lucy Carew and their children, Lucretia (the maker of the memorial) and son, Daniel.

In 1798, Lucy Carew was forty years old, with three children: Lucretia (aged twenty), Daniel (aged seventeen), and Lucy (aged fifteen). It is likely that she began to advertise for “boarders” when her daughters Lucretia and Lucy were of an age to assist her. The elaborate “dressed” silk embroidered memorial Lucretia made in 1800 and dedicated to her sister Lucy (Fig. 1), is evidence that Lucretia was a talented needlewoman and more than qualified to teach. According to needlework scholar Betty Ring, Lucretia’s embroidery was “perhaps planned to demonstrate the ultimate ability of the schoolmistress.” 4

Another “dressed” silk embroidered picture, stitched in 1810 by Lucy Coit Huntington, a relative of Lucy Carew’s husband, is attributed to Lucy Carew’s school (Fig. 2). The painted and “dressed” figures bear a remarkable resemblance to those in Lucretia’s embroidery. Previously the faces in Lucretia’s embroidery were attributed to John Brewster Jr., but given Ehrlich’s research, it seems plausible the faces were painted by one of the Way sisters.

Like most female teachers, Lucy Carew probably started her school to supplement the family income. Born Lucy Perkins (1758–1832), she was one of two daughters of Jacob and Mary Brown Perkins, of Norwich, Connecticut. By age nine, her mother had died and her father married Abigail Thomas, with whom he had seven children. In 1773, at age fifteen, Lucy married twenty-six-year-old Daniel Carew (1747–1813), a saddle maker and merchant.

Prior to marriage, as did most young ladies, Lucy likely received instruction in needlework. No teachers advertised in Norwich during Lucy’s teenage years, though this does not automatically mean an absence of instructors. In nearby New London, in 1772, Elizabeth Hern advertised herself as a needlework teacher, and offered to “take Children from other Towns, and Board and School them, at a very reasonable Rate.” 5 Lucy and her sister could have boarded at this school when their father remarried and began a new family.

In 1776, Lucy’s first child, Lucretia, was born, and died two years later on August 16, 1778. The same year Lucy’s second child, whom they also named Lucretia, was born. A son, Daniel, was born in 1781 and a daughter, Lucy, in 1783. In 1800, Lucy, the youngest child, married James Tillinghast of Providence, Rhode Island, and died giving birth to a son who died eleven days later. And later in 1800, Lucretia Carew stitched her remarkable “dressed” silk embroidery in memory of her sister Lucy (fig. 1).

- Fig. 2: Silk embroidered and painted picture by Lucy Coit Huntington, 1810. The needlework depicts Hector taking leave of his family.Silk and metallic thread, applied fabric, sequins, and paint on silk, 31⅛ x 28¾ inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art; gift of Mrs. Russell Sage (1971.62). Image, © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Although this piece and the Carew memorial are entirely different subjects, note the similarities of the painted faces and background townscapes.

So what is the connection between Mary and Betsy Way and Lucy Perkins Carew? In the previous article, author Brian Ehrlich found that the subject of one of the earliest dressed miniatures attributed to Mary, Polly Carew (1772–1855), was a cousin of Lucy Perkins Carew. Ehrlich proposes that Polly “represents a direct and early connection between the Way sisters and Lucy Perkins Carew…” [and] “…that adolescent Polly, Mary, and Betsy developed a friendship while attending a Carew day school, and that this early instruction enabled a foundation for the developing Way sisters’ talent.”

Mary Way was accomplished in painting and in needlework. In 1796, at age twenty-seven, she was teaching needlework, but not painting, at Mrs. Truman’s house in New London: “Plain sewing, Tambour, and many other kinds of Embroidery by MARY WAY.” 6 In 1809, at age forty, she advertised again, this time at the home of Frances Seabury, New London, where she offered lessons in sewing and painting, “Painting, Tambour, Embroidery, Lace Work on Muslin.”7 In that thirteen-year time frame, could she have learned or taught painting at Lucy Carew’s school, where, in 1798, Mrs. Carew advertised classes in “Painting and Figure”?

Significant portions of both figures 1 and 2 reveal features associated with the Way sisters tradition. In the left foreground of the mourning picture, are two figures, depicting Lucretia, the maker of the piece, and her brother Daniel, with their mother, Lucy Perkins Carew, and father, Daniel Carew, on viewer’s right. Brother Daniel’s profile reveals distinctive eye and inner ear treatment, hallmarks of the Way technique as defined by Brian Ehrlich. The classic five o’clock shadow is evident for the men and Lucretia’s delicately rendered curls are also a Way feature. The three-quarter profiles of the parents are similar to that of Mr. and Mrs. Guy Richards (See figures “o” and “p” in Ehrlich).

In addition, dark fabric pieces rather than embroidery comprise the clothing. The piecing can be seen in the separate application of sleeve fabric as well as the collars for the men. Shear netting and applied overlying fabric ruffles are evident on the women’s dresses. This technique and material is reminiscent of the shawls and headpieces represented on a number of credited Way miniatures. As with many Way dressed pieces, exacting detail is used to produce buttons and button holes. Over painted black highlighting simulates folds in fabric. Though partially embroidered, the foliage chain held by Lucretia is of painted flowers. All are techniques seen in portraits with a prior Mary Way assignment. The fact that Mary Way, Lucretia Carew, and Lucy Huntington all worked dressed miniatures points to instruction from Lucy Carew.

This memorial and embroidery raises the question, however, whether Mary and Betsy Way were instrumental contributors to Carew School pieces as artists, either through commission or possible employment as instructor(s). Comparison of the faces, as previously noted, relate to the sisters’ work. The painted backgrounds may also represent the first documented Way landscapes, an ability that Mary Way advertised in five December 1811 issues of The Columbian while residing and painting in New York City.

Perhaps in the future a document will surface that provides definitive answers, but in the meantime, we can reasonably conclude that there is a connection between the Lucy Carew school and the Way sisters, and that they may have learned the art of creating “dressed miniatures” at Lucy Perkins Carew’s school in Norwich, Connecticut.

Carol Huber is, with her husband, proprietor of Stephen and Carol Huber, leading dealers and scholars in fine antique needlework, Old Saybrook, Connecticut, www.AntiqueSamplers.com.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2014 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. InCollect.com is a division of Antiques & Fine Art, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing.

2. Norwich Packet, April 10, 1799, vol. XXVI; issue 1308; page 3.

3. The Commercial Advertiser (New York, N.Y.), Monday, March 17, 1834. Information provided by Deborah M. Child, independent art historian and museum consultant.

4. Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1993), 23.

5. New London Gazette, March 20, 1772, vol. IX; issue 436; page 3.

6. Connecticut Gazette, November 10, 1796, vol. XXXIII; issue 1722; page 4.

7. Connecticut Gazette, April 12, 1809, vol. XLVI; issue 2370; page 4.