Maine Moderns

Art in Seguinland, 1900–1940

Seguin Island sits at the mouth of the Kennebec River midway along the coast of Maine. The lighthouse on Seguin casts its beacon across two narrow reaches of land to either side of the river as it runs south from Bath and empties into the Atlantic Ocean—a distance of some fourteen miles. Along the way, the Kennebec passes the picturesque villages of the Phippsburg peninsula on the west side and Georgetown Island to the east. From colonial times, the inhabitants of the region had made a modest living farming, fishing, and shipbuilding. By the early 1900s, the region had witnessed the birth of steel shipbuilding in Bath, the arrival of the railroad from Portland and points south, and the construction of small hotels and cottages along the coast for summer visitors and rusticators “from away.” While the local population decreased dramatically between 1900 and 1930, an increasing number of summer residents began to flood the area. At the turn of the twentieth century, real estate developers who sought their business called the southernmost part of Georgetown facing Sheepscot Bay “Seguinland.”

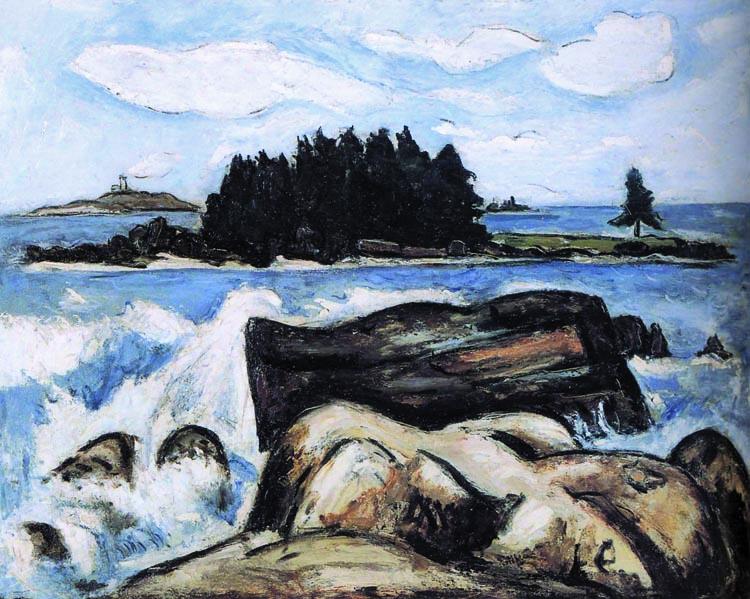

Marsden Hartley began his career in the early years of the twentieth century as a landscape artist, most notably as a painter of the hills and mountains of western Maine. His return to his native state—spurred by his visits to Georgetown and Gaston and Isabel Lachaise—brought him to the coast of Maine where the sea reigns. Jotham’s Island is one of Hartley’s signature Maine landscapes and illustrates

his mastery of the genre of seascape, embodiments of measured fullness and sensuous physicality. The massive boulders and churning surf of the foreground give way to the mid-ground island with its dense stand of pine trees. To the right, on a spur of the small island, stands a single pine, like a lone sentinel, that, in turn, echoes back and left to the far distant island and the tiny triangular point of Seguin Light.

Returning permanently to the United States in the mid-1930s after two decades of travel to Paris, Berlin, France, and Mexico, Hartley reestablished previous connections. Exhibiting at Stieglitz’s Intimate Gallery in 1937, that same year he returned to Georgetown, renting a house down the road from the Lachaises. It was in the latter couple’s garden he painted this image. Still lifes figured prominently throughout Marsden Hartley’s career and represent some of his most exquisite and joyful paintings, largely free from the weight of symbolism. He especially delighted in flower still lifes, favoring certain varieties.

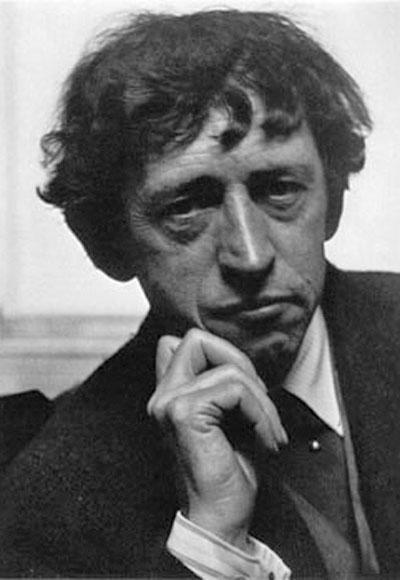

In a 1925 article for Hamilton Easter Field’s magazine the Arts, William Zorach stated, “Real sculpture is something monumental, something hewn from solid mass, something with repose, with inner and outer form; with strength and power.” East Wind, with its solid, heavy style, evokes the sense of mass and monumentality emphasized in this bold ideology. Personified as a woman, East Wind was produced during a period between 1940 and 1955 when Zorach carved an extensive series of reclining female nudes, including a companion piece, West Wind (1955). While most of the works in this series are stone, he cast six bronzes of East Wind using the lost-wax process.

Although William Zorach had largely turned his attention to sculpture by the early 1920s, throughout his life he continued to produce watercolors. He explains in his autobiography, Art Is My Life, writing of his watercolors: “Their spontaneity gives me a certain release and satisfies my love of color. After all, painting was my training and my world for all my early years, and I will always see the world in color as well as in form.” This work illustrates the beauty and seclusion of the area, accessible only by boat or a narrow road and bridge that dominate the foreground of the watercolor. The image also acknowledges modern changes that had come to Georgetown, including one of the early automobiles that began to appear on the island soon after bridges connecting it to the mainland were constructed in the early 1920s.

The Zorach’s connection to the region came indirectly through their professional acquaintances in New York with members of Stieglitz’s circle. Summering elsewhere in Maine, it was Marguerite Zorach’s friendship with Isabel Lachaise that brought them to Georgetown, where they summered for the rest of their lives.

Marguerite Zorach selected a palette of blazing oranges and vivid blues to depict this beach scene on the mudflats in front of her house on Robinhood Cove. The unusual color scheme may well have been suggested by the red hair of her friend and neighbor, Bathena Deermont, seen at the far left of the composition. The girl at the right is Marguerite’s daughter, the artist Dahlov Ipcar, along with her favorite cat, Tookie, and draft horse Kit. While the color combination seems modern, the remnants of an old fishing weir in the center and the workhorse at water’s edge are reminders of more traditional aspects of life in Maine.

Marguerite Zorach selected a palette of blazing oranges and vivid blues to depict this beach scene on the mudflats in front of her house on Robinhood Cove. The unusual color scheme may well have been suggested by the red hair of her friend and neighbor, Bathena Deermont, seen at the far left of the composition. The girl at the right is Marguerite’s daughter, the artist Dahlov Ipcar, along with her favorite cat, Tookie, and draft horse Kit. While the color combination seems modern, the remnants of an old fishing weir in the center and the workhorse at water’s edge are reminders of more traditional aspects of life in Maine.

Gaston Lachaise and his wife, Isabel Dutaud Nagle, the subject of this sculpture and his favorite model, were first in Georgetown in 1923. Woman Walking celebrates the robust vitality of the modern American woman. The geometric folds at the base of her ankle-length skirt, shaped as if in the wake of her confident stride, lend an almost machine-like edge to her presence. One of two bronzes, this version was purchased by photographer Paul Strand, and was included in Lachaise’s

exhibition at Alfred Stieglitz’s Intimate Gallery in 1927; Strand, and his first wife Rebecca, had stayed with the couple during the summers of 1925, 1927, and 1928. According to Strand, before delivering it, Lachaise reworked the bronze in 1928 at his summer studio in Georgetown, eliminating the line of the bodice seen in the other early example, and creating its current gleaming, mirrorlike finish.

An habitué of Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery 291 before it closed in 1917, Gaston Lachaise formally met the photographer and modern art impresario the following year, when his first solo exhibition was on view at the Bourgeois Galleries, New York. Probably around the time of Stieglitz’s marriage to Georgia O’Keeffe in December 1924, Lachaise proposed making the

couple’s portraits, and they sat for him the following June. The busts were still unfinished when Lachaise and his wife moved into their house in Georgetown later that year. There, Rebecca Strand, while visiting them, saw the model for Stieglitz’s portrait and happily reported to its subject: “Lachaise is making a beautiful thing of you—I couldn’t help patting your cheek! It was fine to have your lovely presence in the room even in that form.”

When Paul Strand and his wife Rebecca visited Gaston and Isabel Lachaise in Georgetown during the summers of 1925, 1927, and 1928, Strand felt distanced from his first calling as a still photographer. He had lately been earning his living with a movie camera, but on vacation in Georgetown he began a striking series of natural forms that were a distinct departure from his modernist abstractions done in New York. While in Maine, Strand spent much of his time taking close-ups of the natural forms that surrounded him: the flowers in Isabel Lachaise’s garden, ocean-weathered rocks on the local beaches, and a series of native plant images taken in the woods around Five Islands. He exhibited his Georgetown work at Stieglitz’s Intimate Gallery in 1929 in the critically acclaimed show “Forty New Photographs by Paul Strand.”

The Boston photographer F. Holland Day introduced Agnes Rand Lee, a poet and children’s book illustrator, to Gertrude Käsebier in 1899, and she soon became the subject of some of Käsebier’s best known photographs. When Agnes Lee’s young daughter died and her marriage unraveled, she traveled to Maine to stay at Day’s summer home at Little Good Harbor, where Käsebier photographed the writer contemplating her personal grief at ocean’s edge. Käsebier later joined Clarence H. White and Day as a teacher at the Seguinland Summer School of Photography.

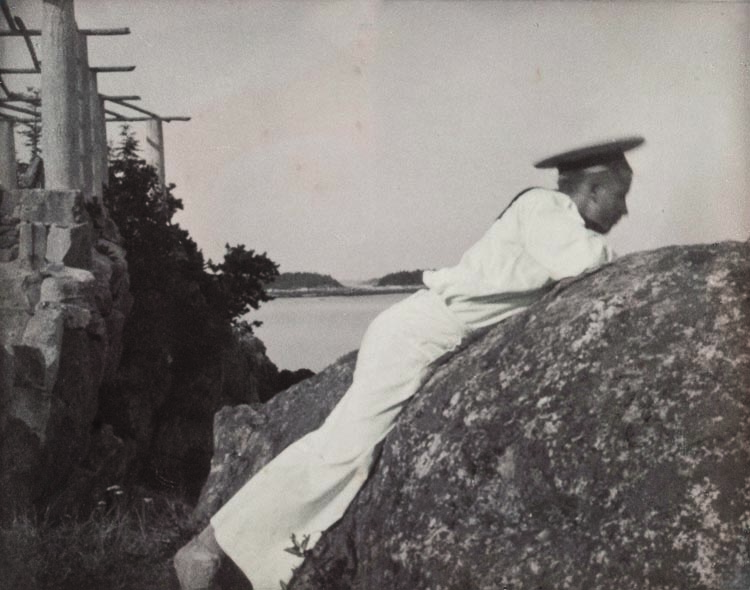

The first modernists to arrive on Georgetown Island were the photographers. They came under the aegis of F. Holland Day, who owned a small fisherman’s house on the bay, which he initially rented in 1901. Within two years, he began inviting friends. In 1905, photographer Clarence White and his wife Jane made their first of many visits, with Jane recalling, “Mr. Day was our Maine enthusiast number one.” Although Day considered all of Clarence and Jane White’s children part of his extended family, he was fondest of Maynard, the second oldest of the couple’s three sons and one of the many young summer visitors whom Day mentored over the years. Born in 1896, Maynard was about sixteen years old when this image was taken; he had been coming to Little Good Harbor nearly every summer for the past seven years. In this image Day posed Maynard—artfully draped over a large boulder—as part of the permanent landscape of his summer retreat. Indeed, Maynard and the whole White family were as much a part of Day’s daily environment as the harbor, the pergola, and the islands on the horizon line in the distance.

Clarence H. White’s first trip with his family to F. Holland Day’s home at Little Good Harbor in the summer of 1905 opened a whole new world of photographic subjects. As he had done at home in Ohio, White experimented with the nude figure in nature; his sons and some of Day’s young guests participating as models. “The Glade,” where this image was taken, became a “surprisingly beautiful outdoor studio.” Boys Wrestling is a particularly atmospheric study for which White used the photogravure process whereby a photographic image is transferred onto a copper plate, which was then inked for printing on paper. The prop of Pan atop a plinth, was a type of symbolic reference to ancient civilization frequently used by turn-of-the-century pictorial photographers in an effort

to link their images with the fine arts. To supplement his income as a teacher in New York, White also ran the Seguinland Summer School from 1910 to 1915.

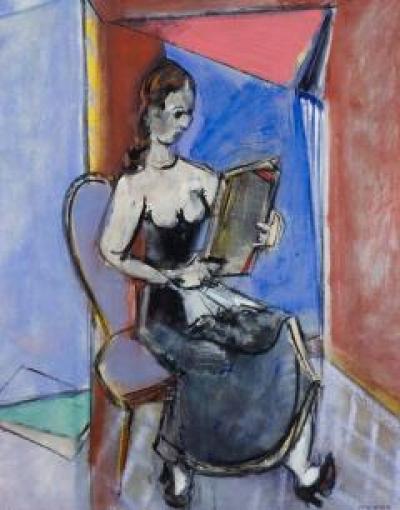

Among emerging American modernists, Weber was perhaps the most avant-garde and well versed in the latest European trends. The Russian-born Weber emigrated to the United States in 1891, returning to Europe in 1905. While in Paris from 1905–1906, Weber produced a number of oil sketches of female nudes influenced by Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, whom he met along with Robert Delaunay and Henri Rousseau. It was not until 1910, shortly after his return to New York, that Weber launched his own Cubist period. That same year he met photographer Clarence White, for whom he taught a series of classes at Columbia University as well as at White’s Seguinland summer school in Georgetown, which Weber ran from 1910 to 1915.

Among the Stieglitz circle, Marin had the most sustained connection to the photographer, whom he met in Paris in 1909; the same year Stieglitz gave Marin his first New York show in his gallery 291. Marin’s connection to Maine also had longevity, first arriving to the Phippsburg peninsula in 1914 because of his friendship with the printmaker Ernest Haskell, who had a summer home at West Point on the Casco Bay side of the peninsula.

The remarkable landscapes along this narrow reach of land quickly came to dominate the repertoire Marin sought out wherever he painted in Maine. Marin’s early Maine watercolors shift between recognizable views and modernist abstractions. In West Point, he framed the static outlines of buildings with agitated brush strokes suggesting movement of wind through pine branches and across water. In 1915, Stieglitz

presented a modest retrospective of Marin’s work and provided funds to support the artist over the summer. To his surprise, Marin used the money to buy “Marin’s Island” in Small Point Harbor.

One indicator of the changes taking place in and around Seguinland was the arrival of modern artists to the weathered landscape of granite rocks, primeval forests, and marshes that bound an ever-changing sea. Between 1900 and 1940, the driving force in this shift was Alfred Stieglitz, a renowned photographer, art critic, and fine arts dealer. Though he never came to Maine, he urged and even financially supported the artists he represented to seek out the restorative and inspiring landscape of Maine. Several of the more important artists in his circle found their way to Seguinland, as did other New York artists who were aware of his influence. They opened a small summer art school, built or bought summer homes there, and formed close-knit friendships.

Unlike Monhegan Island or Ogunquit during this period, Seguinland never developed as a popular artist colony. The number of artists was smaller; they never exhibited their Maine works together or formed a group identity, having little interest in attracting an audience of tourists. New York remained at the center of their professional lives, but Maine sustained an essential part of their creative energy.