Maine Sublime

Frederic Edwin Church’s Landscapes of Mount Desert and Mount Katahdin

|

Fig. 1: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Twilight in the Wilderness, 1860. Oil on canvas, 40 x 64 inches. The Cleveland Museum of Art. Mr. and Mrs. William H. Marlatt Fund (1965.233). Image © The Cleveland Museum of Art. |

We now recognize Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900) as one of America’s great artists of the nineteenth century. Further, many believe his work done in Maine includes some of his most important images, with Twilight in the Wilderness (Fig. 1), based on a sunset he had sketched at Bar Harbor, Maine, a few years earlier, ranking among the dozen greatest paintings in the history of American art.

Church was a public and a private artist. His paintings address both history and autobiography. The work done in Maine during the 1850s and early 1860s, primarily at Mount Desert, embodied sentiments of increasing national strife, in symbolic and suggestive ways, while his career of the later 1860s and into the 1880s was devoted more to Church’s personal time in inland Maine around Mount Katahdin. Where his earlier production was extroverted and exclamatory, the latter was often nostalgic and withdrawn. Over the thirty-year period, Church made more than a dozen trips to Maine, nearly half to Mount Desert during the 1850s and the remainder to the Katahdin region mostly in the two decades following.

How Church came to travel to Maine relates to his initial artistic training. From 1844 to 1846 Church studied with Thomas Cole (1801–1848), the foremost landscape artist of the day, in Catskill, New York. In 1844 Cole decided to make an excursion to the Maine coast and Mount Desert Island, where he filled his sketchbook with more than a dozen pencil drawings of the surrounding area as well as panoramic views of and from the island itself. Over the next year he created at least three canvases based on his trip, including View across Frenchman’s Bay from Mt. Desert Island, After a Squall (Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati).

|

Fig. 2: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), The Wreck, 1852. Oil on canvas, 30 x 46 inches. James M. Cowan Collection of American Art. The Parthenon, Nashville, Tennessee (29.2.14). Image © 1929 The Parthenon Museum, Nashville, Tennessee. |

After Cole’s death in 1848, Church’s maturing style followed the evolving taste toward a more exacting and explicit recording of sites, but his teacher’s work in that exotic coastal wilderness obviously impressed him deeply.

| |

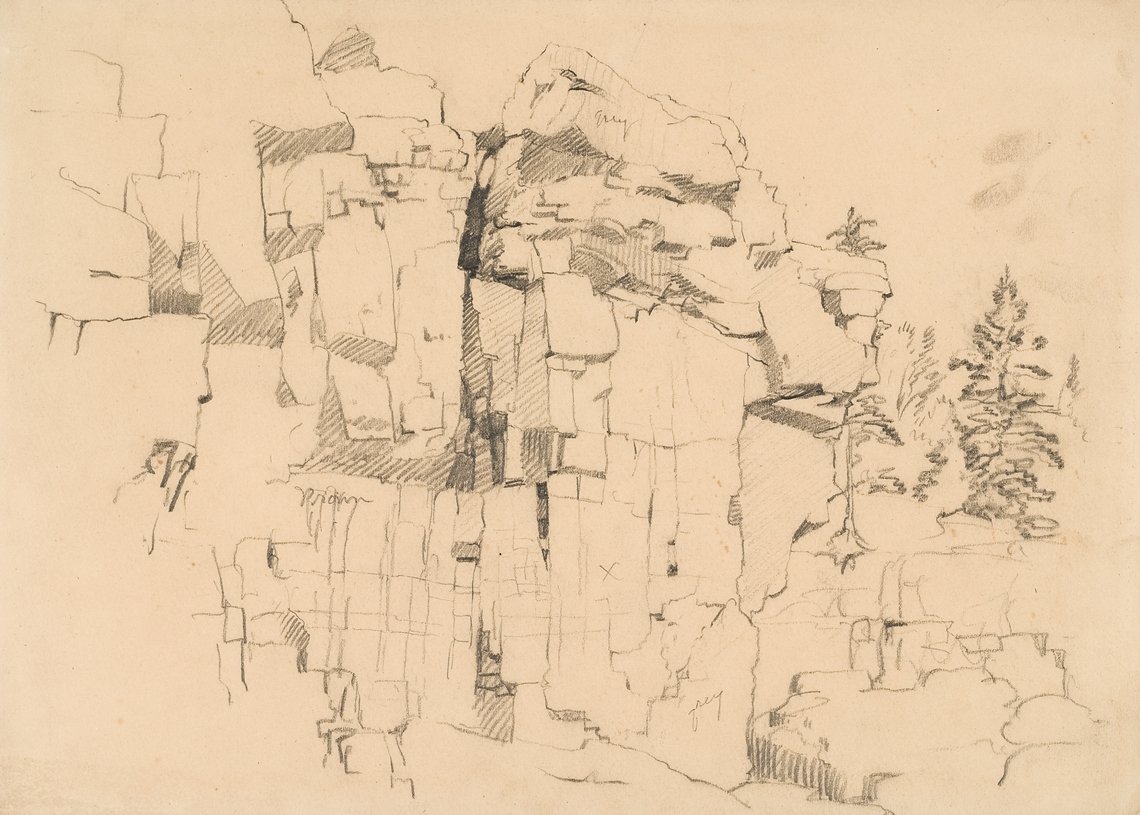

Fig. 3: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900). Granite Cliffs, Mount Desert Island, ca. August 1850. Graphite on light brown paper, 10-13/16 x 15 inches. Olana, OL (1977.112) |

At the same time, several other artistic and literary forces then coming to fruition—Andreas Achenbach (1815–1910), Fitz Henry Lane (1804–1865), and New England author Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862)—shaped Church’s ambition to try new subjects along the Maine coast. In the exclamatory language of the sublime, these influential artists celebrated nature’s dual pastoral and awesome, even destructive, elements. Church would tackle a similar subject when he painted The Wreck (Fig. 2) at Mount Desert.

On his first trip to Maine in 1850, Church was eager to visit particular views his mentor Cole had sketched. Granite Cliffs, Mount Desert Island (Fig. 3) is a close-up sketch of the compressed cubic blocks of quartz and granite across the rock face of Otter Cliffs. Birch Tree Struck by Lightning (Olana, Hudson, New York) executed in the manner of Cole, suggests God’s hand in the life of nature, but Church’s sketches were far more specific and identifiable in their execution than Cole’s.

Church found the lumber mills, either under construction or in operation around the island, a lively subject to sketch, later producing the finished oil painting Lumber Mill, Mount Desert Island, circa 1850 (Fig. 4).

|

Fig. 4: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Lumber Mill, Mount Desert Island, ca. 1850. Oil on canvas, 14 x 20 inches. Private collection. Image courtesy David Stansbury. |

|

Fig. 5: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Newport Mountain, Mount Desert, 1851. Oil on canvas, 21¼ x 31¼ inches. Private collection, promised gift. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. |

During his first trip Church also undertook several drawings of Newport Mountain from varying distances and slightly different angles, almost as if he were photographing it with changing zoom and wide-angle lenses. In his New York studio later that fall, he began to compose a large canvas of the view (Fig. 5), synthesizing selected aspects he had recorded by pencil on separate sheets. Featuring a man in the foreground pulling in over the rocks the remains of a wrecked vessel, the sky is a crisp deep blue and autumn colors dot the forests, but it is the turbulent surf and looming mountainside that address nature’s more awesome character.

In October 1851, Church returned to Mount Desert, actively painting and sketching, gathering material for The Wreck (see fig. 2). This canvas shows some crucial changes in Church’s work: No human figures are present, and an old schooner forced onto the rocks now occupies the foreground. Its aft mast is broken, but the one forward with its cross bar above forms a clearly silhouetted cross against the sky in an image of salvation.1 Brilliant afternoon sunlight breaks through the stormy clouds to illuminate the horizon line with its redemptive force. With this work Church decisively turned his attention to the evening hours, whose expressive colors he would explore in shifting ways over the rest of the decade.

|

Fig. 6: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Twilight Mount Ktaadn [sic], ca. 1858–60. Oil on paper mounted on board, 10½ x 13⅝ inches. Private collection. |

|  | |

| Left: Fig. 7: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Sunset, Bar Harbor, ca. September 1854. Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 10⅛ x 17¼ inches. Olana, OL (1981.72). Right: Fig. 8: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Maine Sunset, ca. 1856. Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 10 x 17½ inches. Olana, OL (1980.1889). | ||

In 1852 Church made his first excursion to Mount Katahdin. Far fewer sketches survive from this trip, but the great northern peak clearly possessed his attention. A powerful oil study depicts the mountain silhouetted at twilight (Fig. 6). The artist envisioned Katahdin as a sublime continental complement to the coastal positioning of Mount Desert.

Further trips to Mount Desert Island produced a variety of sensational sunsets (Figs. 7 and 8). One of Church’s traveling companions recorded, “Mr. Church says this island is remarkable for fine sunsets; and our stay here is daily proving his impressions just.” 2

Church painted his greatest Maine sunset in 1860, when the nation was on the threshold of civil war, and almost all scholarship on Church sees Twilight in the Wilderness (see fig. 1) as emblematic of this explosive moment. Three aspects dominate this pivotal picture: the meteorological, the spiritual, and the national. The cloud formation reflecting the setting sun is several thousand feet high in the atmosphere—what weather reporters today would describe as a sharp front about to bring impending change— is depicted in a preliminary sketch (Fig. 9). Tied to the meteorological display is the artist’s strong religious faith. He presents the landscape as a day of judgment. On the right, three trees appear in various stages of decay and collapse, signifying the cycle of time. Church also universalized the setting: it remains a Maine subject, but it is also a continental landscape, pertinent to the state of the nation and the impending civil war.

|

Fig. 9: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Twilight, a Sketch, 1858. Oil on canvas, 8¼ x 12¼ inches. Olana, OL (1981.8). |

In 1860, Church’s personal life and energies shifted. He purchased a farm near Hudson, New York, where soon after marrying Isabel Carnes he built a cottage. Family affairs seized his attention with the birth of his first two children, born in 1862 and late 1864. In celebration of their births, he painted small companion canvases, Sunrise and Moonrise (both at Olana, Hudson, New York). His joy was dashed the following year with the deaths of both from diphtheria; this was a moment in his art of turning from public to personal meanings.

Four more children were born over the next few years, as domestic life took hold. Church added to and landscaped his Hudson property, and in 1867 purchased the hilltop with the intent of building a new home. Construction of the Persian villa was under way between 1870 and 1872 (Fig. 10). Church blended eastern and western elements into its detailing and designed the views from major windows and balconies to frame living landscape compositions. The house and 250-acre designed landscape, later named Olana, are a work of art in their own right. Thus domestic life and space drew his principal emotional and creative drives during these years.

|  | |

| Left: Fig. 10. Peter Aaron, View across the Lake, Olana, photograph, 2010 (2010A53.442). © Peter Aaron/OTTO. All rights reserved. Right: Fig. 11: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Wood Interior Near Mount Katahdin, ca. 1877. Oil on paper mounted on canvas, 12-5⁄16 x 17-1/16 inches. Olana, OL (1980.1871). | ||

|

Fig. 12: Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Mount Katahdin from Millinocket Camp, 1895. Oil on canvas, 26½ x 42¼ inches. Portland Museum of Art, Maine, Gift of Owen W. and Anna H. Wells. in memory of Elizabeth B. Noyce (1998.96). |

In 1878, the artist purchased the fifty-acre Stevens Farm on the south shore of Millinocket Lake, which brought him back to Maine for successive stays in the years following. The property gave him unobstructed views across the water to the mountain, and he repeatedly sketched it and the surrounding woods in pencil and oil studies (Fig. 11). Many of these are beautiful and technically precise vignettes, but they seldom led to singular completed projects as they had earlier at Mount Desert.

After his final visit, in1881, Church continued to paint occasional canvases of Mount Katahdin, some of good size. Very different from the visual exultations he recorded on his first visits, these are calm and reflective, often bathed in pink light. The foregrounds are mostly empty and often in shadow, the peak reached across an expanse of flat open water. The mood seems wistful and elegiac. Rather than inviting, these works were a meditation on something enduring at a great distance away. Debilitated by arthritis, Church’s last dated canvas was Mount Katahdin from Millinocket Camp, painted in 1895 (Fig. 12), which he presented to his wife, Isabel, as a birthday gift. His accompanying note read, “Your old guide is paddling his canoe in the shadow, but he knows that the glories of the Heavens and the earth are seen more appreciatively when the observer rests in the shade.” 3 He had been painting the great summits of Maine for forty-five years, from 1850 to 1895, expressing the most public and personal themes of his lifetime.

1. Charles Colbert, Haunted Visions: Spiritualism and American Art (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 117.

2. Anne Mazlish, ed., The Tracy Log Book, 1855, A Month in Summer Bar Harbor, Maine (Bar Harbor: Acadia Publishing Company, 1997), 57. In August and September of 1855 Church was part of a large vacationing group of family and friends organized by Charles Tracy of New York (who later became the father-in-law of J. Pierpont Morgan). Tracy kept a lively diary of their time on the island, which provides us with a glimpse of the artist’s congenial side, as he was known to sing and play the piano, tell stories, fish, and cook for the group.

3. Frederic Church to Isabel Church, November 10, 1895.

John Wilmerding is Sarofim Professor of American art, emeritus, at Princeton University and a noted scholar of American art and cultural studies. Formerly, he was a visiting curator in the Department of American art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art and served as Senior Curator and Deputy Director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2013 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.