Matisse and Printmaking

|

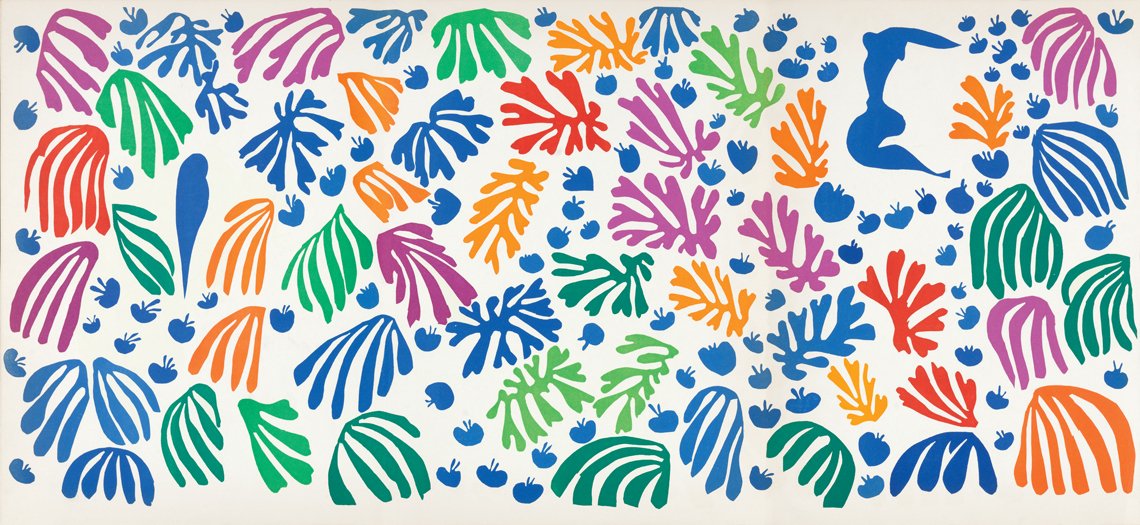

Henri Matisse (1869-1954), La Perruche et la Sirène, 1954. Lithograph. H36 x W77.5 cm / H14.2 x W30.5 in. |

|

Imagine a time, not so long ago, when the role of a painting, drawing or print was to recreate the past or depict the world as it was seen by the naked eye.

This is the history of western art from the Renaissance until the mid 19th century. It all changed when artists in France, primarily, but also elsewhere, broke with classical and conventional styles of the past and began to experiment with ways of seeing and depicting the world. Today we refer to this historical moment in western art history as Modernism, a period style that must also be understood as a part of broader social, economic, political and cultural changes associated with Modernity.

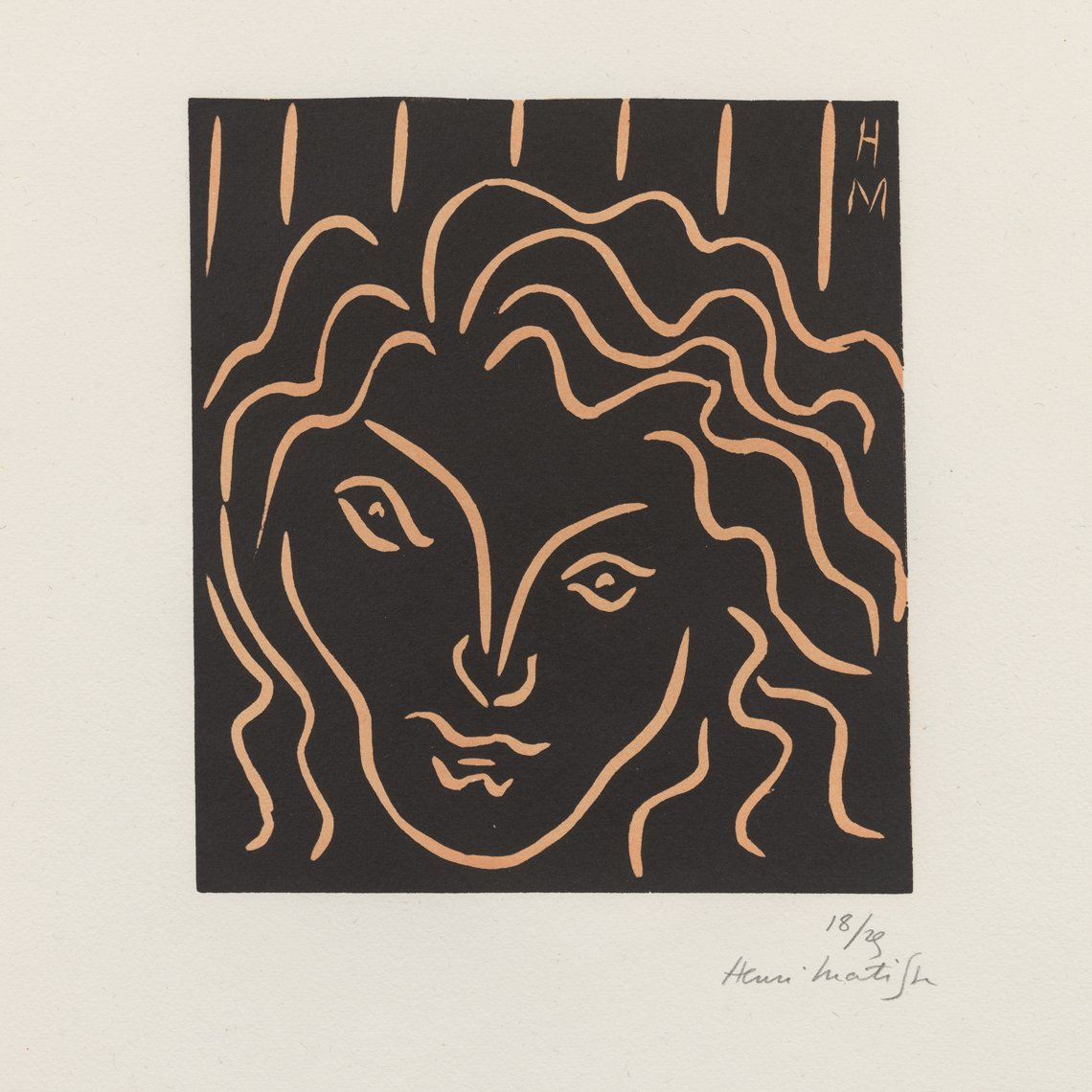

|  | |

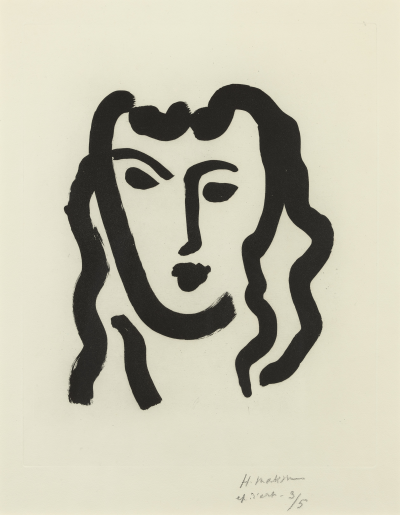

| Left: Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Patitcha, 1947. Aquatint on BFK Rives paper, Edition of 25. H55.5 x W38 cm / H21.9 x W15 in. Right: Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Grande masque, 1948. Aquatint on Marais paper, Edition of 25. H65.5 x W50 cm / H25.8 x W19.7 in. | ||

The idea, state or quality of being ‘modern’ took on various identities in art. During the first two decades of the 20th century in Europe, art movements of almost every imaginable style followed one another, each claiming they offered or possessed a radical discovery or advancement that surpassed all predecessors. The movements were accompanied by manifestoes, often written by the artists, in which they extolled a new, guiding artistic technique, process, practice, subject, attitude or thought.

Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse are two artists associated with this radical and influential rejection of well established art making traditions in the name of innovation and the new. The art critic Robert Hughes coined the term ‘shock of the new’ in the 1970s to describe how provocative these modern ideas were: for example, back in 1905, art critic Louis Vauxcelles coined the term ‘Fauves’, French for ‘wild beasts’, to describe the experiments with violent, wildly expressive color in the work of a group of Parisian painters including Henri Matisse, Georges Braque and Andre Derain.

Looking at the work of Matisse today it is hard to imagine what all the fuss was about. His subjects are traditional, mostly reclining female nudes or faces, quiet landscapes or domestic scenes; imagery typically found in traditional European art from previous centuries. Picasso aggressively sought out new thematic inspiration by incorporating broader imagery of ‘modern life’, as writer Charles Baudelaire famously characterized the society of late 19th century France, such as beggars, street children, prostitutes as well as elements of African or ‘primitive’ art which he encountered on visits to the natural and ethnological museums in Paris. Matisse was aware of the innovations of Picasso, his younger Spanish contemporary and the father of the art movement that became known as Cubism, but he chose to focus on formal and stylistic innovation, in particular a conscious interest in the play of shapes, lines and colors.

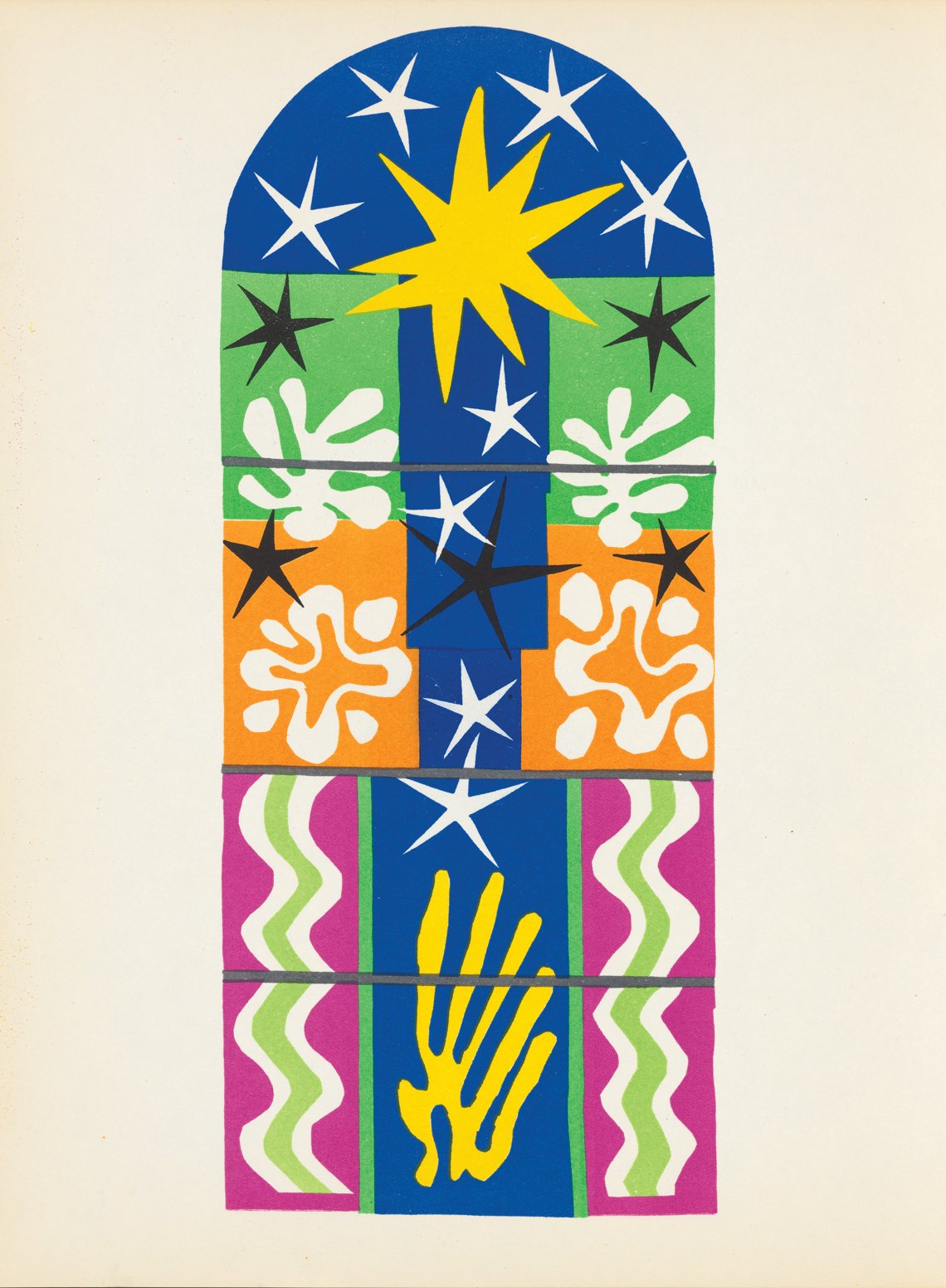

|  | |

| Left: Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Nuit de Noël, 1954. Lithograph. H35.5 x W26.5 cm / H14 x W10.4 in. Right: Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Corbeille de bégonias I, 1938. Linocut on wove paper, Edition of 25. H38.3 x W39.7 cm / H15.1 x W15.6 in. | ||

| |

Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Corbeille de bégonias I, 1938. Linocut on wove paper, Edition of 25. H38.3 x W39.7 cm / H15.1 x W15.6 in. |

Matisse is most famous as a painter and a vibrant colorist—Fauvism, as an art movement based around the expressive use of color, evolved around 1900 with Matisse and Derain as the leaders. He also made sculpture and was a natural and gifted draftsman as evidenced in many drawings and works on paper including numerous prints along with his innovative, colorful paper cut-outs in which shapes and colors are used to create pleasing, expressive collage compositions. His work goes much further than Picasso in terms of formal innovation in 20th century art insofar as abstract visual forms become the subject of an artwork—something Picasso never fully embraced. If Formalism is the defining hallmark of Modernism, understood as a period style, Matisse is one of its legendary innovators.

Jay McKean Fisher writes in an essay for an important 2019 exhibition, Matisse as Printmaker: Works from the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation, organized by the American Federation of the Arts at the Fundación Canal in Madrid, that Matisse made somewhere between 800 and 900 individual prints and that were reproduced in mostly small editions of between about 25 to 50 impressions each. The final number of prints produced however is believed to exceed more than 10,000 as he was also involved directly in as many as 50 different book illustration print projects, resulting in multiple prints of images of various quality produced as part of larger, sometimes undocumented book editions.1 Matisse was, then, a prolific print maker.

Matisse worked ‘episodically’ on print projects, embracing the medium with enthusiasm for a period of time then stopping completely, only to take up printmaking once again years later.

— John Yao

|

Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Tête de femme en mascaron, 1938. Linocut in black and red on G. Maillol paper, Edition of 25. H40 x W30 cm / H15.7 x W11.8 in. |

Matisse’s first prints date to around 1900 and include a somber, studious drypoint self portrait, Henri Matisse Gravant (1900–1903), which is interesting if unremarkable as an artwork. It was followed by etchings, woodcuts and lithographs of mostly female nudes and faces and which all have the casual, even observational quality of working studies from an artist’s sketchbook but which also provide us with a unique, unfiltered insight into the artist’s early working process and creative vision. They also begin a fifty year love affair for Matisse with making prints: later in life he even had a printing press in his studio and made portraits of visiting friends and family. Once, famously, he sketched the outline of a visitor onto an etching plate in less than five minutes.

In an essay for a 2017 exhibition of Matisse’s prints at the Bernard Jacobson Gallery in London, home to one of the world’s largest private collections of Matisse prints for sale, the art critic John Yao notes that Matisse worked ‘episodically’ on print projects, embracing the medium with enthusiasm for a period of time then stopping completely, only to take up printmaking once again years later. Yao, like many other art historians before him, reminds us that Matisse chose almost exclusively to make prints in black and white in spite of advances in color printmaking and the fact that, as a painter, he is associated with color. The reasons for Matisse’s attachment to black and white prints are unknown, though Yao speculates that the artist wanted his work to be compared or measured against the great printmakers of the past.2

|

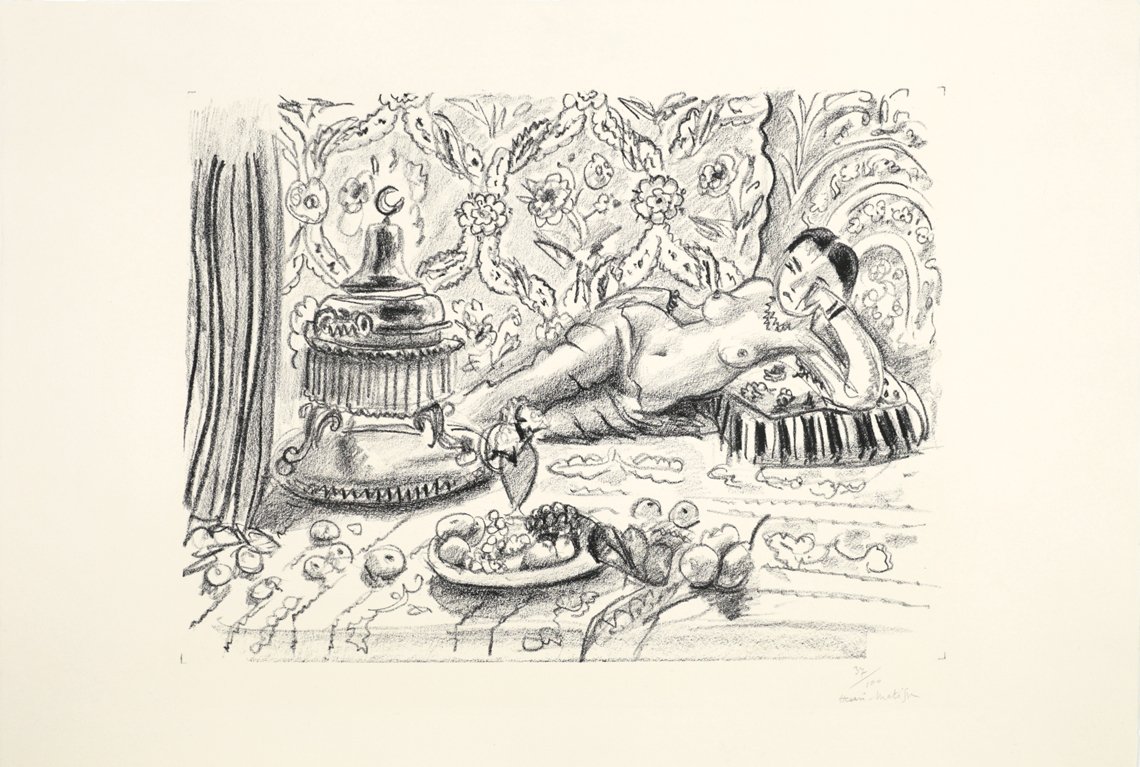

Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Odalisque, brasero et coupe de fruits, 1929. Lithograph on Arches Velin paper, Edition of 100. H38 x W57 x D0 cm / H15 x W22.4 in. |

|

Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Repos sur la banquette, 1929. Lithograph on Arches Velin paper, Edition of 50. H49.5 x W65.5 cm / H19.5 x W25.8 in. |

Matisse’s most ambitious and famous color print is Dance, based on a mural commissioned in 1930 by the American collector Dr. Alfred Barnes for the painting gallery in his mansion outside of Philadelphia. This is the basis of what is today the Barnes Foundation in downtown Philadelphia. Matisse reworked his classic theme of the dance, inspired originally by Catalan fisherman dancing on the beach. The mural was an oil on canvas produced in 1932–33 and was installed to embellish three arches above French windows in the painting gallery. Subsequent prints were produced in an edition of 50 and are held in many important museum collections including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Jazz (1947) is perhaps Matisse’s best-known, best-loved book of color illustrations and consists of print reproductions of 20 of his earlier, colorful cut-out paper collages using a stencil process known in French as pochoir. The original portfolio took two years to finish. Matisse gravitated more towards book illustration later in his life as his health deteriorated, with the majority of his book projects carried out during the Second World War, in the 1940s, and leading up to his death in 1954.

Matisse employed different printmaking techniques at different times in his life. He initially used etching and drypoint in which lines are engraved into a metal plate with etchant, an acid, or, in the case of drypoint, a kind of engraving in which the artist draws onto a metal plate, made of copper, with a pointed instrument. He also used lithography, a printmaking technique in which the artist draws on a flat stone; and linocut, in which a design is carved into a soft linoleum tile; and woodcut, a similar process using a carved piece of wood; and aquatint, a form of etching that creates shaded tonal areas using plates brushed with a partial layer of varnish. Then there are monotypes, made between 1914-1917, a unique image printed from a polished glass, stone, or metal plate which has been drawn with a design in ink or oil paint.

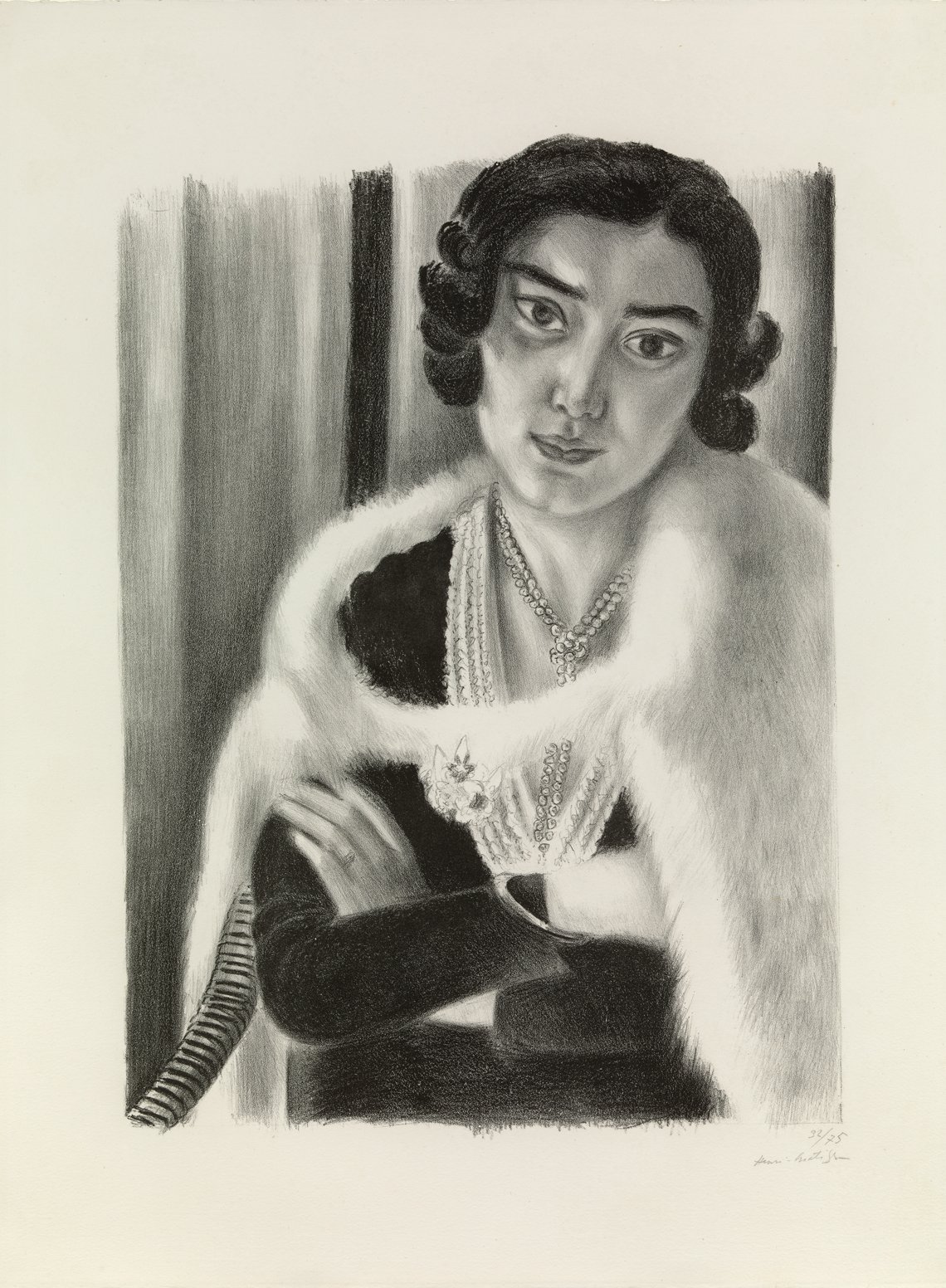

|  | |

Left: Henri Matisse (1869-1954), La Persane, 1929. Lithograph on Arches Velin paper, Edition of 50. H63 x W44.5 cm / H24.8 x W17.5 in. Right: Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Le renard blanc, 1929. Lithograph on Arches Velin paper, Edition of 75. H66 x W50.5 cm / H26 x W19.9 in. | ||

Every print medium is distinct in its own way not just in terms of the process and materials but presents vastly different visual, surface, textural qualities. Notice the linear simplicity of Matisse’s etchings, or the graphic, angular, sculptural quality of forms in the woodblock prints and linocuts, or the painterly composition and highly worked, finished detail of lithographs, or the moody atmospheric qualities of the aquatints. Monotypes are another thing entirely, highly sought after because each image is unique and handmade. They are individual artworks in their own right, unlike the rest of the print processes here in which multiple impressions are taken from the same surface or ‘plate’ and therefore the same composition is designed to be more or less reproducible—albeit in a limited edition. Monotypes are paintings.

The defining feature of Matisse’s prints, what distinguishes and elevates him above all other printmakers is the sensuality and fluency of his lines.

The graphic simplicity with which Matisse was able to depict a body, or a face, or a form is remarkable. He was a master draftsman, drawing from life, able to conjure an image from seemingly nothing but lines, shading and shadow. Even the line itself is not just a simple long narrow mark or band connecting dots but can be thicker, thinner, darker, lighter, jagged, straight, bent depending on the weight of the artist’s hand. This directness, fluidity, simplicity, energy is part of the great appeal of Matisse’s prints, creating a sense of casual intimacy as opposed to the formality of his oil paintings. Though he drew from life, using models, his prints are infused with what we might call the “dramatic spirit” of a subject. That is how I think of it.

|

| Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Jeune femme enserrant son genou gauche, 1929. Drypoint on Chine appliqué on Arches Velin paper, Edition of 25. H28.5 x W38 cm / H11.2 x W15 in. |

|

| Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Jeune femme contemplant un Bocal de Poissons Rouge, 1929. Etching on Chine appliqué on Arches Velin paper, Edition of 25. H28.5 x W38 cm / H11.2 x W15 in. |

| |

Henri Matisse (1869-1954), Nu au miroir marocain, 1929. Etching on Chine appliqué on Arches Velin paper, Edition of 25. H37.5 x W28 cm / H14.8 x W11 in. |

Twirling lines, twisting designs and decorative motifs abound throughout his prints. Witness an abundance of sparkles, stars, dots, grids, and cross hatching patterns. It is almost as if Matisse couldn’t help it. Joy and visual pleasure are their own justification and it is clear Matisse enjoyed making prints, along with a fondness for sensual interiors, lush decoration in the form of drapery, bedspreads, wallpaper, carpets, tiled floors, chair caning, curtains, furniture upholstery, mosaics as well as, draped over his female models, embroidered dresses, shawls, necklaces, and hats. His love of pattern and design is often linked to his early upbringing in northern France, a manufacturing center for textiles and later luxury fabrics used in the fashion trade, but the vivid, colorful decoration that so characterizes an animates his best paintings as well as prints gave Matisse free reign to exercise a fascination for the formal elements of a composition, the play of pure shapes and lines.

Matisse’s prints ask formal questions and leave the viewer wanting to know more. Subtle adjustments in the pictorial structure such as a close cropping of a face, a figure partly cut out of the picture frame, or the rendering of a scene from an unusual or disorienting point of view are all intentional visual devices designed to disrupt what at first glance seems like a conventional composition. Everything seems whimsical but it is brilliantly innovative, economical and efficient.

Matisse was not a technical innovator in the printmaking media he employed, far from it, but from time to time made his own modifications to the printmaking processes to suit specific needs—with lithography, John Yao has observed, he sometimes drew his images directly onto paper, later transferring the design over to the stone plate. But he also drew directly on the stone when the composition included shading, contrast and depth. Both techniques can be observed in prints throughout his long career.

As mentioned, Matisse’s prints are really about the lines, often as few as possible, seemingly effortless, deftly used to transfer an observation into an evocative image. Paying attention to the lines is the pathway to an understanding of Matisse’s prints and love of printmaking, which was an obvious extension of his love of drawing—the elemental, irreducible component of his art practice regardless of medium in which he worked. Immediacy is a word that comes to mind when comparing the artist’s prints and his drawings but it is present throughout everything which he did. In Matisse’s prints we find joy, pleasure, but also a window onto his true artistic soul.

|

1. Jay McKean Fisher, Henri Matisse—But Why Printmaking?”, “Matisse as Printmaker: Works from the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation, organized by the American Federation of the Arts at the Fundación Canal in Madrid, 2019.

2. John Yao, Henri Matisse Prints, exhibition catalog, Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London, 2017.