Military Powder Horns in the Concord Museum Collection

|

|

by David F. Wood

|

Fig. 1: (flat) Stephen Parks powder horn, probably Concord, Mass., 1747. Concord Museum Collection, Anonymous Gift; Gift of the Cummings Davis Society; Gift of the Philip and Betsey C. Caldwell Foundation; Gift of Mr. Charles N. Grichar (2007.266); and (upright) Joseph Gar / Stephen Parks priming horn, probably Concord, Mass., about 1747. Concord Museum Collection; Gift of Cummings Davis (1886) (A102). Photograph by David Bohl. |

|

recent reinstallation of the Concord Museum’s collection of objects associated with April 19, 1775, the first battle of the Revolutionary War, has brought renewed attention to the museum’s powder horns. Made of cow horn trimmed, scraped, and fitted with a fixed wooden plug at one end and a removable stopper at the other, powder horns were a ubiquitous element in the kit of the colonial citizen-soldiers who provided support for the professional soldiers (Regulars) fighting Great Britain’s dynastic and imperial wars in the New World. Militia service was required of all adult males in the British colonies, and in contrast to the regular army, militiamen armed and equipped themselves. The powder horns, then, were personal items, and no regulation prohibited their embellishment. Over the second half of the eighteenth century the decoration of military powder horns in America developed into a distinctive art form, then all but disappeared.

|

The study of American military artistically engraved powder horns took a great leap forward with Bill Guthman’s 1993 catalogue and exhibition Drums A’beating, Trumpet’s Sounding, hosted by the Concord Museum in 1994. With rigorous connoisseurship Guthman was able to trace an artistic lineage that, remarkably, may have originated in Concord, then flourished in the forts manned for King George’s War (1744–1748), the French and Indian War (1754–1763), and the Siege of Boston (1775–1776). This line is perhaps most clearly seen in the work of professional horn engravers who, for a few shillings, could embellish a horn, but can also be discerned in the work of many who seem not to have been professionals. The Concord Museum collection includes horns that are part of this artistic tradition, but the collection is particularly distinguished by the horns that were at the North Bridge. These horns were used to load the muskets that fired, in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s stirring phrase, “the shot heard round the world.”

The earliest horns in the collection are two that belonged to Stephen Parks of Concord, both decorated by the same carver (Fig. 1). Parks farmed near Nine Acre Corner, a part of Concord that became part of Lincoln in 1754. The horn with the smaller stature and brass mounts is an early form that hearkens back to the days before flintlocks, though it is dated 1747. The larger horn has all the features that Guthman identified as characteristic of the first phase of distinctly American military engraved powder horns, all of which are dated 1746 or 1747. As seen on the larger horn, these characteristics include the letters formed of parallel lines joined by ladder-like hatching with triangular serifs, colons composed of a pair of lozenges each bisected by a line, the finely engraved figures of two figures (perhaps the Duke and Duchess of Cumberland (Fig. 2), and the scattered menagerie of animals labeled with their names (Fig. 2a). At the base of the larger Parks horn is a double border, one resembling an embroidered band, and one a double row of opposed scallops separated by diagonal hatching. This border matches closely the border on the David Fletcher horn (Maine Historical Society).

|  | |

(Left) Fig. 2: Detail of Stephan Parks’ larger horn (2007.266). (Right) Fig. 2a: Detail of Stephan Parks’ larger horn showing a Doe, nursing “Fan”, and other animals (2007.266). Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. | ||

|

Fig. 3: Stephen Parks’ smaller horn, with inscription from Joseph Gar (A102). Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. |

In all, Guthman identified three horns as the product of the individual he termed the Smith-Fletcher Carver, and the same carver worked the two Stephen Parks horns. The smaller Parks horn has the inscription “Joseph:Gar/Gift:To/Stephen/Parks” (Fig. 3). A reasonable interpretation of that inscription is that Joseph Gar carved the horn and gave it to Stephen Parks. That would identify Joseph Gar as the Smith-Fletcher carver. Regrettably, Joseph Gar remains unidentified. He might have been a neighbor of Parks in Concord, or Parks and Gar may have served together during the Louisburg campaign. Joseph Gar clearly encountered Stephen Parks, David Fletcher, William Smith, and Meshach Taylor somewhere and carved their powder horns, but no service records from 1746–1747 survive for any of them.

| |

Fig. 4: Abner Hosmer powder horn, Acton, Mass., 1745–1755. Concord Museum Collection; Gift of Miss Elizabeth S. Hosmer (1936) (A2053). Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. |

Some features of this group of horns, notably the suckling fawn (here spelled “FAN”) (fig. 2a), reappear in horns carved during the French and Indian War, which Guthman grouped under the heading Lake George School. During this period the art of the military engraved powder horn became more sophisticated, to no small degree owing to the artistry of a company clerk from Shrewsbury named John Bush. This carving tradition was ultimately transmitted to the horns carved around Boston during the Siege, an example of which is discussed below.

Twenty-one-year-old Abner Hosmer of Acton was carrying his father’s powder horn when he was killed in the first round of firing at the North Bridge. The undecorated horn (Fig. 4) was preserved by his family, complete with its woven wool strap and wooden stopper engraved “IH” (Jonathan Hosmer), until given to the museum in the twentieth century. A letter written by Jonathan Hosmer on April 10, 1775 (private collection), proved woefully prophetic with its prediction that if the Regulars came to Concord there would be “bloody work.” In common with several other horns with histories of use on April 19, the Hosmer horn has an earlier form of attachment for the strap, a tab integral to the horn.

|

Fig. 5: Amos Barrett powder horn, Concord, Mass., 1775. Concord Museum Collection; Gift of Frederick S. Richardson, Peter H. Richardson, and Joan R. Fay (1994.63). Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. |

|

Fig. 6: Samuel Jones powder horn, Concord, Mass., 1774. Concord Museum Collection; Gift of Cummings Davis (A101). Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. |

Two of the horns in the collection with North Bridge associations were decorated by the same carver. The first of these (Fig. 5) belonged to Amos Barrett, a twenty-three-year-old corporal in David Brown’s minute company on April 19. Fifty years later Barrett vividly recalled what transpired at the bridge, including his orders not to fire unless fired on, then to fire as fast as possible; the splashes of three warning shots in the river; and the volley that killed Abner Hosmer.

The second (Fig. 6) belonged to thirty-four-year-old blacksmith Samuel Jones who was a member of one of Concord’s two militia companies and, like Amos Barrett, had mustered at Wright Tavern when the town bell rang the alarm at two in the morning. Jones’s horn is inscribed “Samuel Jones His Horn” and dated 1774. The presence of the initials “SI” on another part of the horn seems redundant with respect to ownership but could be interpreted as Jones signing as maker. If that is the case, Jones should also be given credit for the decoration of Amos Barrett’s horn. Barrett may have turned to his Concord neighbor to tattoo it for him during the Siege of Boston, perhaps outside Boston where Jones was on picket duty in May 1775 (Amos Barrett’s movements in May are unrecorded), or perhaps in Concord. Like the Abner Hosmer horn, Amos Barrett’s horn had a projecting lobe that was pierced with two holes for tying the strap. These lobes seem to have had a tendency to fail, and on this horn the lobe was removed and a gun screw (a sear spring screw, as armament specialist at Skinner Auctions, Chris Fox, has noted) was driven into the plug to serve as the strap attachment.

|

Fig. 7: Jonathan Gardner powder horn, Roxbury, Mass., 1776. Concord Museum Collection: Gift of Mrs. Robert M. Bowen (1972) (A116). Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. |

|

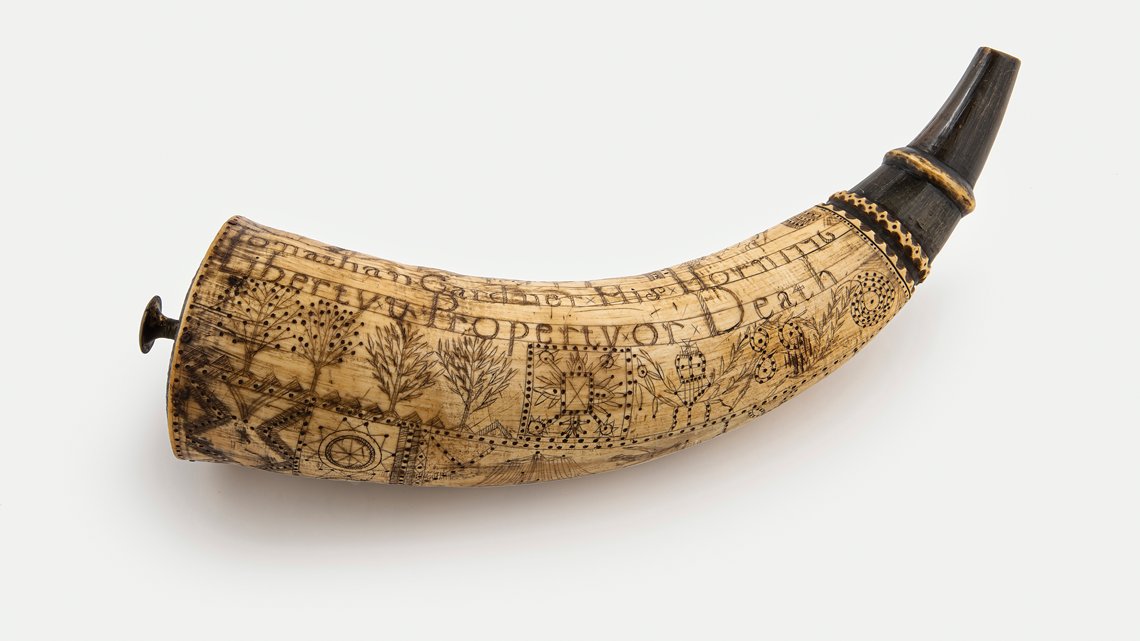

Fig. 7a: Detail of Gardner horn (A116). Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. |

The artistic quality of Siege of Boston horns can be very high, and the Jonathan Gardner horn (Figs. 7, 7a) is a good illustration of the fact. Bill Guthman characterized this as “an extremely visual horn,” deeply carved and well composed, and concluded that its owner hailed from Sunderland, Massachusetts, serving in Roxbury and Dorchester Heights in the fall of 1776. The line of marching soldiers is one of the motifs Guthman traced from the horns produced around Lake George in the 1750s to the last full flowering of the art during the Siege. The phrase “Liberty & Property or Death” reflects John Locke’s concept of Natural Law, which was frequently posited in opposition to the laws of parliament during the lead-up to the Revolution.

The final horn under consideration here is the Reuben Hosmer horn (Figs. 8, 8a). Characterized as a “fine Siege of Boston horn” in Guthman’s catalogue, Reuben Hosmer’s horn was carved by the same individual who carved the horn of his brother Nathaniel (Historic Deerfield). Both Reuben and Nathaniel were born in Concord, in 1739 and 1731, respectively. Hosmer’s horn features compass-worked pinwheels similar to those seen on Samuel Jones’s horn carved the year before and a pike-like fish frequently seen on horns from the 1740s onward.

In the fall of 1940, the Reuben Hosmer horn came up for auction in the sale of the collection of James G.S. Dey, a Syracuse, New York, dry goods merchant. The auction took place at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in midtown Manhattan and the auctioneer was O. Rundle Gilbert, best known for his part in dispersing the 3600 crates of patent models that had been sold by the U.S. Patent Office. The Concord Museum found out about the horn when Gilbert previewed part of the Dey sale at the Museum of the American Indian in lower Manhattan. Reuben Hosmer’s horn, inscribed “Concord May 1775” and therefore carved just weeks after the epochal events of April 19, was irresistibly appealing.

|

Fig. 8: Reuben Hosmer powder horn, Concord, N.H., May 1775. Concord Museum Collection; Gift of Mrs. Edward Motley (1940) (A2003.1). Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. |

|  | |

| (Left) Fig. 8a: Detail of Reuben Hosmer horn (A2003.1). Photograph by Gavin Ashworth. (Right) Fig. 9: Receipt from O. Rundle Gilbert auctioneer, for the Reuben Hosmer horn (fig. 8). Concord Museum Collection Records. | ||

At the auction, Dorothea Miller, the sister-in-law of the Concord Museum’s collections manager, bid on behalf of the museum. In a letter to the donor of the acquisition funds, she recounted a flurry of intrigue before the hammer came down. “I asked Mr. Grancsay of the Metropolitan [Metropolitan Museum of Art curator of arms and armor Stephen V. Grancsay, whose American Engraved Powder Horns (1945) is a landmark study of the subject] and Mr. Pell of Ticonderoga [Stephen Hyatt Pell who restored Fort Ticonderoga, which his family had owned since 1820] please not to bid on it. They were very nice about it—as museum people always are to each other.” The collusion, if decidedly unethical, seems to have been effective, as the horn made just $9 at the sale (Fig. 9).

Dorothea Miller was a bit smug about the affair (“I think Mr. Grancsay is envious for he mentioned the horn in a lecture he gave a few weeks ago. . .”) but had in fact been mistaken. The “Concord” so enticingly inscribed on the horn did not indicate Concord, Massachusetts, where Reuben was born, but Concord, New Hampshire, where he mustered before marching on to Boston. Reuben Hosmer was one of several members of the Hosmer and Barrett families who moved to New Ipswich, New Hampshire, in the 1760s, and also established the nearby town of Mason.

|

I am indebted to the late Bill Guthman (as are we all) for helping me understand and appreciate some of the rich complexity of American military powder horns, and to Joel Bohy, Chris Fox, and Ed Kane for their help with this article.

David F. Wood is curator of the Concord Museum, Concord, Massachusetts.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2021 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|