Neoclassical Art in the Eighteenth Century by Edgar Peters Bowron

|

by Edgar Peters Bowron

Neoclassicism is the name given to the various classicizing styles that developed in Europe in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and which profoundly influenced the fine arts, decorative arts, and architecture. Artists and craftsmen found inspiration in the order, clarity, and reason of the art of ancient Greece and Rome and sought to re-create the spirit and forms of the classical world. From each of the different disciplines came something at once new and classically inspired.

Neoclassicism drew its main inspiration from Italy, where it was nourished by the artistic traditions of ancient Rome and by the excavations begun at Herculaneum in 1738 and, a few years later, at Paestum and Pompeii. The contemporary interest in exploring Europe’s ancient heritage is exemplified by Giovanni Paolo Panini’s Interior of an Imaginary Picture Gallery with Views of Ancient Rome (Fig. 1). The interest in antiquity reached its peak in the eighteenth century in the work of Robert Adam, Pompeo Batoni, Edmé Bouchardon, Antonio Canova, William Chambers, Jacques-Louis David, Gavin Hamilton, Anton Raphael Mengs, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Hubert Robert, and Josiah Wedgwood. The works of these artists and others are showcased in the exhibition Antiquity Revived: Neoclassical Art in the Eighteenth Century, organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in association with the Musée du Louvre in Paris, where a related exhibition opened in December 2010. Houston is the sole U.S. destination for this traveling exhibition of 135 paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures, ceramics, and furniture ranging in date from the 1720s to the 1790s.

|

|

| Fig. 1: Giovanni Paolo Panini, Italian (Roman), 1691–1765, Interior of an Imaginary Picture Gallery with Views of Ancient Rome, 1757. Oil on canvas, 67-3/4 x 90-1/2 inches. Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gwynne Andrews Fund, 1952. |

Panini’s magnificent imaginary interior hung with paintings of the monuments of “ancient” Rome and a companion canvas with a gallery showing paintings of “modern” Rome, also in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, were commissioned in 1757 by the French ambassador to Rome, Étienne-François de Choiseul-Stainville (1719–1785), the future Duc de Choiseul. Here, Panini catalogued the obvious sights of ancient Rome in the form of individual, framed canvases displayed as if within an actual picture gallery. Seen are most of the ancient monuments in and around Rome familiar to eighteenth-century artists and tourists visiting the city, including the interior and exterior of the Pantheon, the Colosseum, and the Temples of Vespasian. Equally interesting is the selection of antique marbles arranged throughout the composition, several of which were among the most admired works of art by Neoclassical painters and sculptors.

|

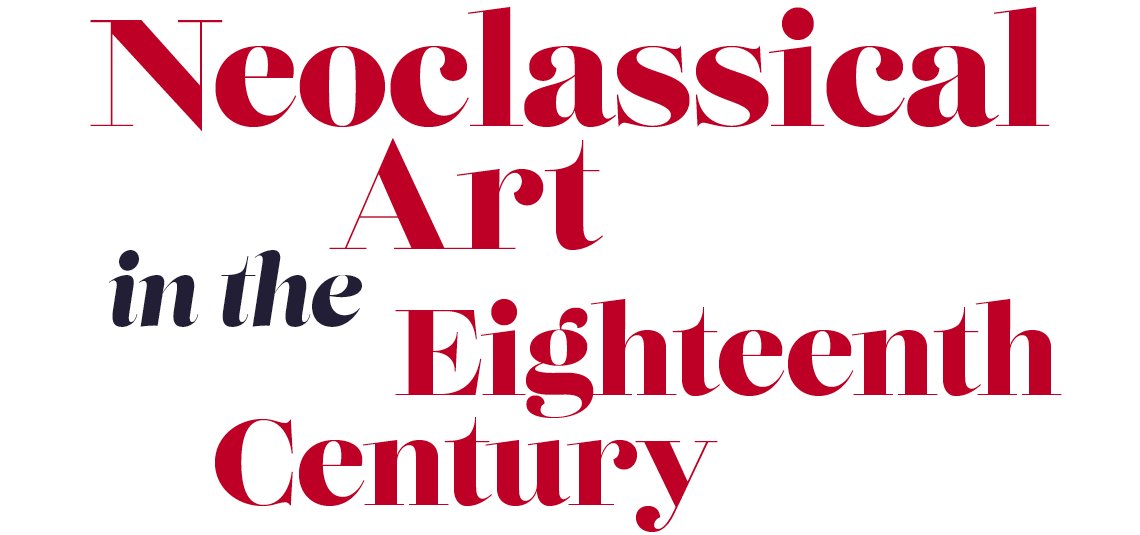

| Fig. 2: Joseph-Marie Vien, French, 1716–1809, A Greek Maiden at the Bath, 1767. Oil on canvas, 35-1/2 x 26-1/2 inches. Courtesy, Museo de Arte de Ponce, The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc., Puerto Rico. |

Joseph-Marie Vien’s style à la grecque made its appearance in a series of one-, two-, and three-figure compositions in the late 1750s and early 1760s of pretty young women in “antique” settings that convey a simple Neoclassical “look.” In these small cabinet paintings he established his métier with a pictorial formula that secured his position as the first French artist of the eighteenth century to embrace the Neoclassical ideal. A Greek Maiden at Her Bath was commissioned by Étienne-François de Choiseul-Stainville, Duc de Choiseul (1719–1785), and by 1770 hung in the bedroom of his hôtel particulier in Montmartre in Paris, along with two semi-erotic paintings by Jean-Baptiste Greuze and a Sacrifice to Priapus by Jean Raoux. Vien’s pure, cool colors and porcelain-like technique; the chaste, idealized young women; the “antique” setting; and the accumulation of pseudo-antique trappings are all unashamedly classical, suffused with a delicate, if sentimentalized, poetic quality.

|

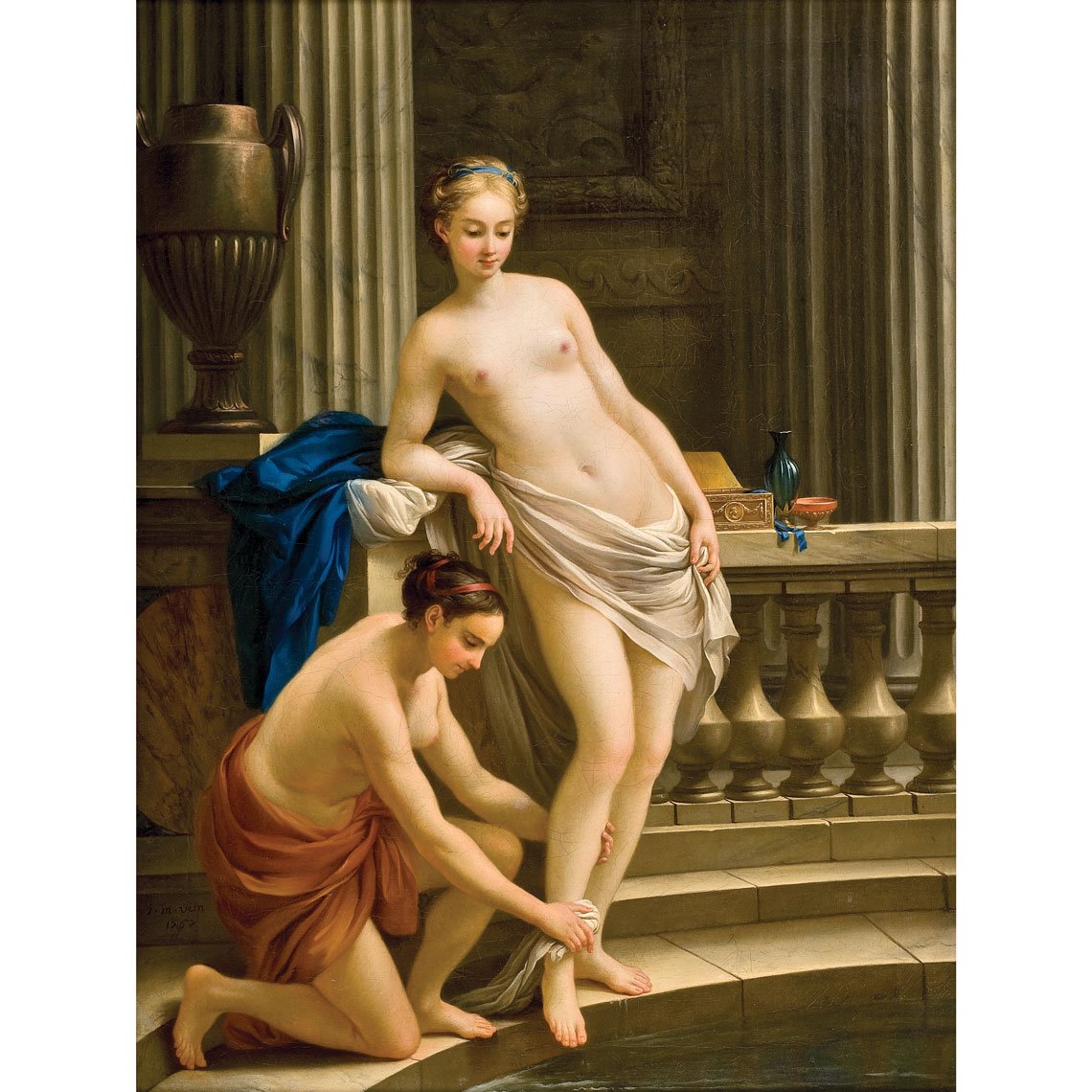

| Fig. 3: Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, Italian, 1716/17–1799, The Emperor Caracalla (188–217), ca. 1750–70. Marble, 28 x 21-1/2 x 13 inches. Courtesy, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. |

Busts of Caracalla were popular in the eighteenth century, especially among English collectors. Numerous ancient prototypes abounded, and ever since Michelangelo adapted the vehement gesture of Caracalla’s head turning sideways for his Bust of Brutus (1540s; Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence), antique busts of the emperor had served as models for portraiture through the eighteenth century. Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (AD 188–217), more familiarly known as Caracalla, was remembered for the massacres and persecutions he authorized throughout the empire. Caracalla’s official portraiture accords with descriptions of his appearance and character. The features of the antique prototypes that seemed to have appealed to the eighteenth-century imagination were the emperor’s close-cropped hair, cuirass and toga, the strong turn of his head, furrowed brow, and tense facial features, and threatening, pugnacious scowl. No more forceful evocation of ancient history can be imagined, but the aesthetic appeal of Bartolomeo Cavaceppi’s marble is equally obvious and the bust is a masterpiece of the sculptor’s art with its skillful drill-work in the antique manner, notably in the handling of Caracalla’s beard and hair.

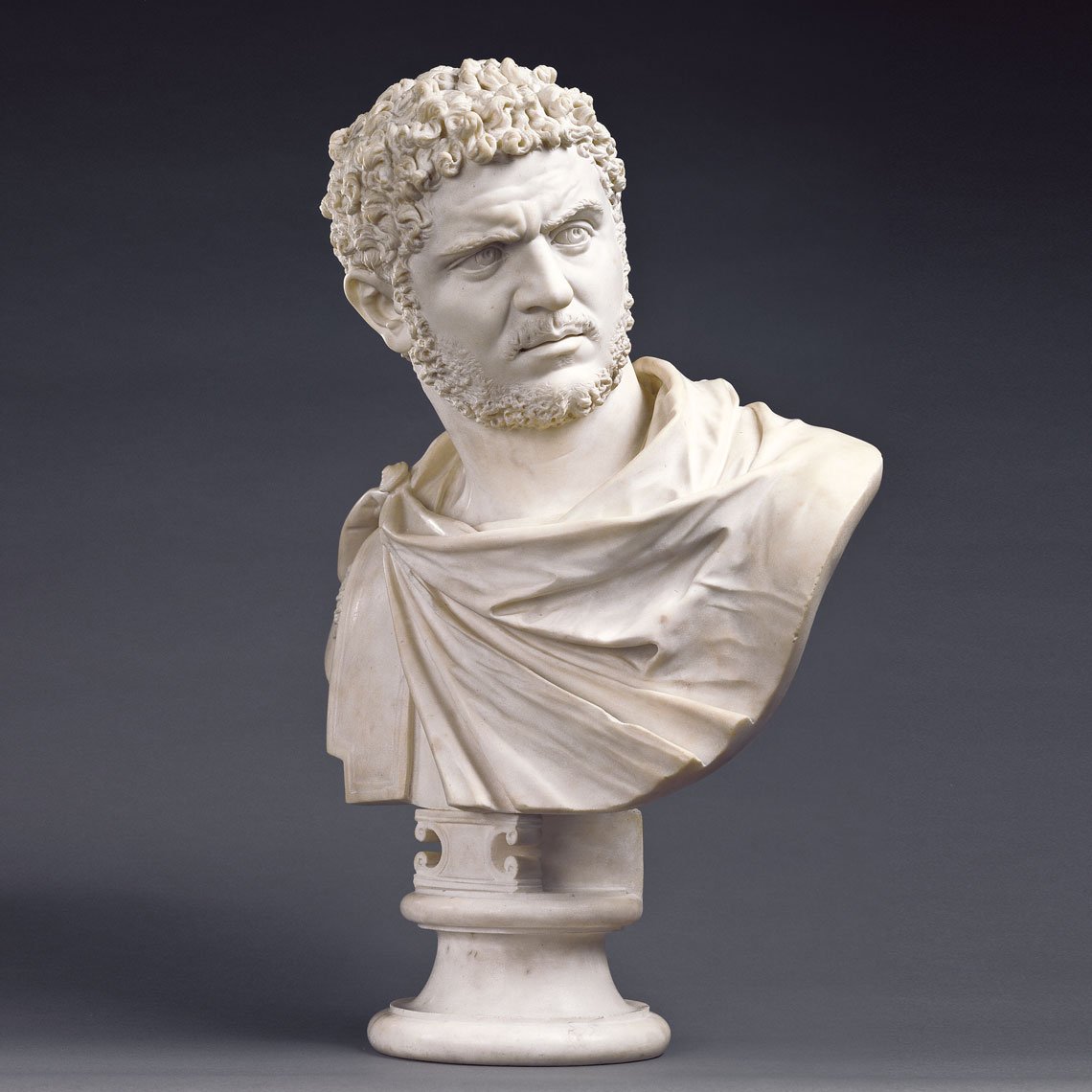

|  | |

| Fig. 4: Christoph Unterberger, Austrian, 1732–1798, Study for a “Composition with Ignudi and Grotesques and an Allegory of Painting,” ca. 1776. Study for a “Composition with Ignudi and Grotesques and an Allegory of Sculpture,” ca. 1776. Oil on canvas, each 43-1/2 x 12 inches. Courtesy, Worcester Art Museum, Mass., Eliza S. Paine Fund in memory of William and Frances T.C. Paine. | ||

Christoph Unterberger was among the first eighteenth-century Roman artists to study the decorative painting of the Renaissance, and became the leading exponent of this style of painting in the city. He put this knowledge to use in the decoration of a room in the Museo Pio-Clementino in the Vatican Palace known today as the Vestibolo Quadrato. These beautifully painted allegories of Painting and Sculpture served as sketches for his designs and consist of familiar components of Renaissance grotteschi (grotesques), a type of fanciful wall decoration characterized by the use of interlinked floral motifs, animal and human figures, and masks. The style was derived originally from the ornament found in certain Roman buildings, which in the sixteenth century spread to most of the countries of Europe. The luxuriant leaf and flower decorations of the upper zones of each of Unterberger’s compositions are supplemented by additional classical motifs and elements, such as vases, tripods, grotesque masks, medallions, and garlands.

|

| Louis Gauffier, French, 1761–1801, Cleopatra and Octavian, 1787–1788. Oil on canvas, 33 x 44-1/8 inches. Courtesy, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, Purchased with the aid of the Art Fund (1991). |

This small, colorful and highly polished painting provides an early example of the Egyptomania that swept France and Britain in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The subject is derived from the Greek historian Plutarch (ca. 46–120 A.D.), whose Lives was popularized in the eighteenth century by Charles Rollin’s Histoire Romaine (Paris, 1730–1738). Octavian, following his defeat of Marc Antony at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, visited the Egyptian queen Cleopatra. When she failed to convince him of her innocence and remorse for the part she played in opposing him, she directed his attention to her excellent relations with his great-uncle Julius Caesar reflected in the letters and portraits of him displayed in her room.

“Egyptianized” motifs can be seen in Gauffier’s painting in the statues in niches on the rear wall of Cleopatra’s chamber and her day-bed decorated with hieroglyphs derived from the obelisk of Thutmosis III at the Lateran, and a figure of a kneeling Pharaoh. The English designer Thomas Hope (1769–1831), who produced the most accomplished interior of the Egyptian Revival at his house in London, copied exactly the throne with Egyptian winged sphinxes on which Octavian sits for the design of four seats in his so-called “Egyptian” or “Black Room.”

|

| Jacques-Louis David, French 1748–1825, The Oath of the Horatii, 1786. Oil on canvas, 51-1/4 x 65-5/8 inches. (130.2 x 166.2 cm.) Courtesy, The Toledo Museum of Art, Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey, 1950. |

The paintings of Jacques-Louis David, generally considered the epitome of Neoclassicism, with their heroic subjects, measured compositions, solidly constructed forms, and emphatic linearism captured the imagination of a public grown weary of the frivolities of the Rococo. His enormous canvas representing the Oath of the Horatii (1784; Musée du Louvre, Paris), first shown in Rome, where it was painted, and subsequently in Paris, where it was included in the Salon of 1785, exerted a tremendous influence on French history painting with its radical content and severe style. In this celebrated work, which has been so closely linked with the radical political ideals propagated during the French Revolution, David depicted a decisive episode recounted in Livy’s History of Rome, which was typical of the themes of patriotic fervor and morally uplifting subjects demanded from artists by philosophers of the Enlightenment. This reduced version of David’s monumental painting was made for the renowned collector of French art, Joseph François de Paule, Comte de Vaudreuil (1740–1817) in 1786.

|

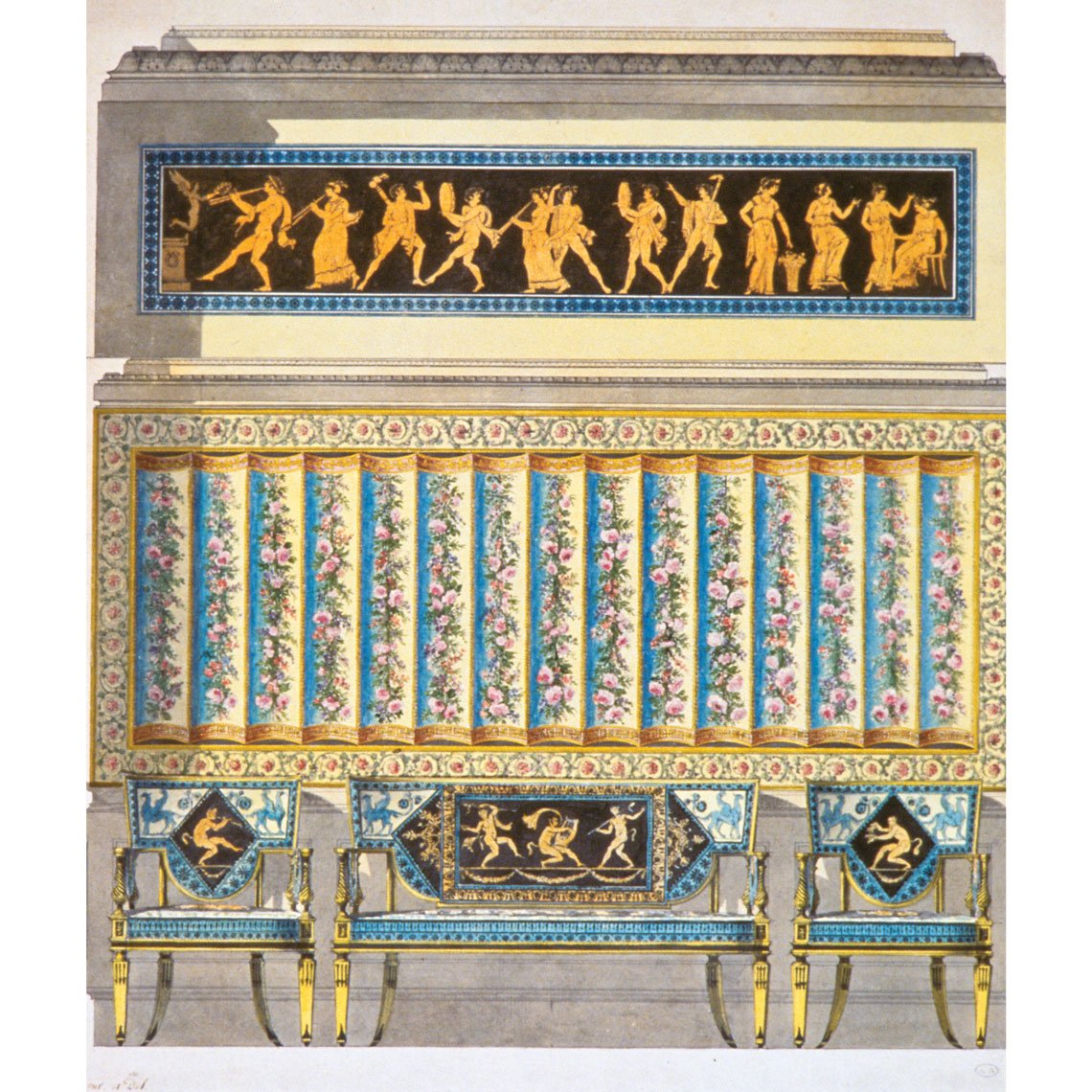

| Jean-Démosthène Dugourc, French, 1749–1825, Wall Decoration and Furniture in the Etruscan Style, ca. 1790. Watercolor, pen and black ink, gouache, 17-1/2 x 15-1/8 inches. Courtsy, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. |

Interior design and the decorative arts played a pervasive role in the dissemination of Neoclassicism throughout Europe in the late eighteenth century, but by the end of the century “Neoclassicism” was distinguished by an astonishing heterogeneity. Eclectic architects and designers like Dugourc conceived projects for buildings and their interiors in the Gothic, Turkish, Chinese, Egyptian, and Etruscan styles. This beautifully finished drawing represents a wall décor in the so-called Etruscan style, harking back to the simple, linear style typical of Greek vase painting and to the wall paintings of Herculaneum and Pompeii. A narrow panel at the top of the wall depicts a group of men and women in Greek costumes as they dance across the space in a frieze-like arrangement that recalls red-figured Greek vases of the Classical period. Antique elements are repeated below on the backs of the sofa and chairs, which are embellished with diamond and lozenge-shaped black panels with Greek dancers.

|

| English pier table, 1770 or later. Beech and spruce and gilding, 357/8 x 55-1/2 x 23-3/8 inches. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Rienzi Collection. |

By the mid-1760s, designers like Robert Adam, who produced and popularized the best Neoclassical interior decoration, invigorated British furniture design with a fresh, delicate classicism. Adam was anxious to reflect the designs of the ancients, rather than imitate them blindly, and his work was not a mere pastiche of architectural elements. Neoclassical design in the hands of Adam and his associates and followers was extraordinarily diverse and lent itself to an astonishing variety of applications. This sophisticated, semi-elliptical Neoclassical pier table, one of a pair, is a case in point. Although the designer and maker are unknown, the piece exemplifies the influence of the ancient world on the eighteenth-century cabinetmaker’s art with its long, thin, straight legs and use of familiar classical motifs of vases, garlands, swags, fluting, spiraling reeds, and guilloches. Designed to be placed with its back against a wall or pier, a candelabrum or girandole would have been placed on the table over which a large pier glass likely hung.

|

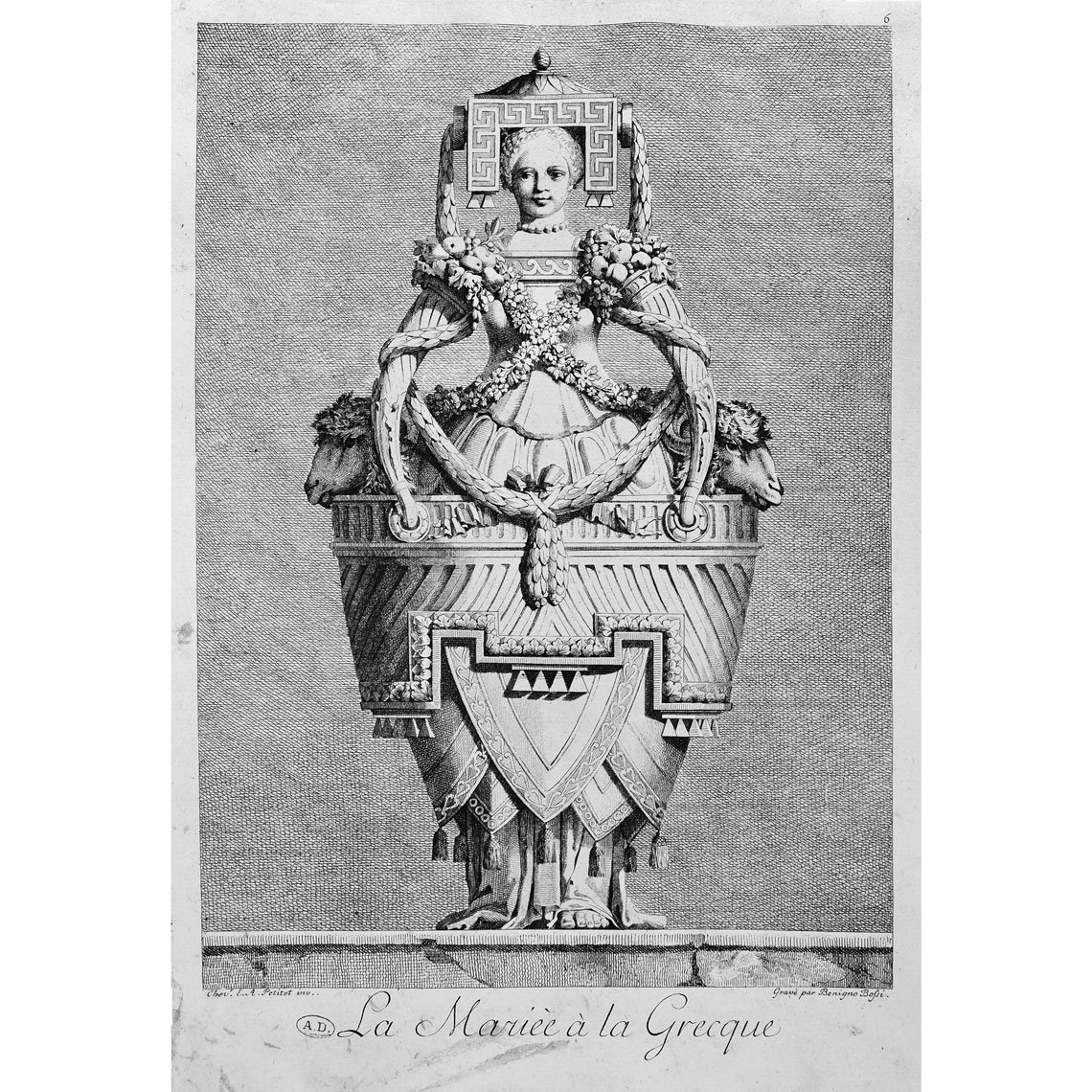

| Ennemond-Alexandre Petitot, French, 1727–1801, The Greek Bride, 1771. Plate from the Mascarade à la Grecque (etched by Benigno Bossi), 10-5/8 x 7-1/4 inches. Courtesy, Bibliothèque des Arts Decoratifs, Paris. |

The fascination for all things Grecian, considered by some to be superior to Roman culture, played itself out in many ways in the late eighteenth century. Although he trained as an architect, Petitot is better known for his masquerade costumes “à la grecque,” a wicked send-up of the archeological vogue for antiquity to which he himself had contributed when younger. In a suite of prints published by Benigno Bossi in 1771, Petitot depicted a series of nine personages, among them a monk, shepherd, shepherdess, bride, and groom, attending a “Greek masquerade.” Each figure’s fanciful ensemble features a variety of classicizing design elements in a tongue-in-cheek presentation.

|

| Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, French, 1755–1842, Joseph François de Paule, Comte de Vaudreuil (1740–1817), 1784. Oil on canvas, 52 x 387/8 inches. Courtesy, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Gift of Mrs. A. D. Williams. |

Joseph-François de Paule, Comte de Vaudreuil (1740–1817), enjoyed a prominent place at the French court during the last decades of the ancien régime. Income from his family’s Caribbean sugar plantations allowed him to acquire impressive collections of art, furniture, and curiosités, and arrange them in his Paris house and at his Château de Gennevilliers. Madame Vigée Le Brun admired the handsome nobleman greatly and portrayed him several times. In this version, Vaudreuil is resplendently attired with his various chivalric decorations, his amiable animation reinforcing his reputation as the best amateur actor of his day. The splendid Neoclassical carved and gilded fauteuil in which Vaudreuil sits was ordered from the fashionable Parisian furniture-maker Georges Jacob and exists today in the Queen Marie Antoinette apartments at Versailles.

|

The exhibition explores, from various points of view, how the renewal of classical taste found its roots in ancient sources. Because the Neoclassical movement that captured Europe in the 1770s and 1780s evolved in fits and starts and because there is no one definitive “Neoclassical” style, one of the goals of the exhibition is the examination of the varieties of stylistic reform that engaged artists, writers, theorists, and patrons. For example, what began as a rejection of the artificialities and extravagances of late Baroque and Rococo art in favor of a style inspired by Hellenistic sculpture was nonetheless enriched by that art and architecture that advocates of the classical claimed to abjure. Thus, the semi-erotic brand of Neoclassicism practiced by the French painter Joseph-Marie Vien can be interpreted as both Rococo and Neoclassical. But the artist’s Greek Maiden at the Bath (Fig. 2) is nonetheless a seminal work of eighteenth-century French genre painting à la grecque (as the nascent Neoclassicism was then called) which transports the viewer into a private world of classical antiquity.

Other artists approached the classical world head-on. Italian sculptor Bartolommeo Cavaceppi‘s marble bust of the Emperor Caracalla (Fig. 3) is a copy of an ancient portrait of the notorious Roman emperor. Christoph Unterberger’s designs (Fig. 4) for the interior of the Museo Pio-Clementino in the Vatican are inspired by antique Roman decoration seen through the eyes of Raphael.

Antiquity Revived: Neoclassical Art in the Eighteenth Century, through May 30, 2011, is drawn from the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Museum, Musée du Louvre, National Galleries of Scotland, British Museum, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, as well as numerous other European and American museums and private collections. A catalogue accompanies the exhibition. For information call 713.639.7300 or visit www.mfah.org.

Dr. Edgar Peters Bowron is the Audrey Jones Beck Curator of European Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2011 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|