Out of Africa: A Private Collection of Tribal Art

- The Ginzbergs’ home, situated on an inlet off Long Island Sound, was designed by architect Charles Forberg, son-in-law of Walter Gropius. It consists of a central core with a living room, flanked on the right by a perpendicular wing containing a garage, kitchen, dining room, and two bedrooms, and on the left by a smaller rectangle housing a den, master bedroom, and upstairs bedroom and study.

The diamond–shaped windows in the gable ends of the house, brackets at the roofline, and exterior cladding and framing reference the traditional Japanese architecture that influenced Gropius and Forberg.

Thirty-five years ago, Denyse Ginzberg experienced what the French call a coup de foudre, which literally translates into English as a “lightening bolt,” but usually connotes love at first sight. Shopping in the home décor department of Lord & Taylor in New York City, she had her first look at African masks and figures. The pieces were not antique, not even very good, as she would later learn, but in their own way, stunning. “I loved those things. I couldn’t even look at the furniture,” she recalls.

A year passed before the couple bought their first African mask in a Greenwich Village shop. “It was not good,” Denyse says. “We still have it in a closet.” “We started with statues and masks, the things you typically think of,” Marc recounts. “We were so happy to be collectors, we made some awful choices.”

Nonetheless, Denyse’s coup de foudre set the Ginzbergs, who recently celebrated their fifty-first wedding anniversary, on a path. “We bought things because we liked them,” Denyse adds. “We didn’t spend much. We finally went to a symposium at Columbia University, where we met curators and other collectors, and we invested more in books about art than in art. Very slowly, we started buying small, very good pieces.”

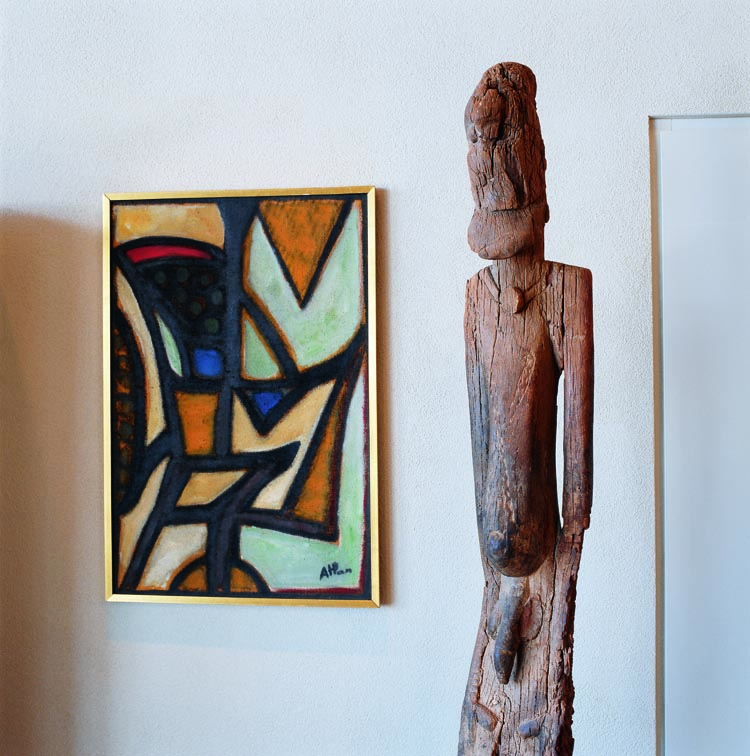

- On a wall of the living room an Indian screen affords a filtered view of the dining room. Beneath the console table are Tuareg (left) and Yemeni (right) boxes. The sculpture by contemporary artist Amy Uhl complements the Nancy Flanagan painting and echoes the curvilinear decoration on the Luo shield from Kenya. The metal coffee table and the small side table are by Philip and Kevin LaVerne. The room’s neutral colors defer to the objects it contains and its view of Long Island Sound.

Over the next twenty years, the couple assembled one of the finest collections of African art in America, even as prices for masks and figurative sculpture rose astronomically. Marc says, “We always liked to upgrade, but prices had gone up so we couldn’t collect at that level any longer. We decided to sell that collection.” Dispersed through L. & R. Entwistle & Co. Ltd, London, pieces from the Ginzbergs’ first African art collection were purchased by individual collectors and museums, including the Dallas Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City.

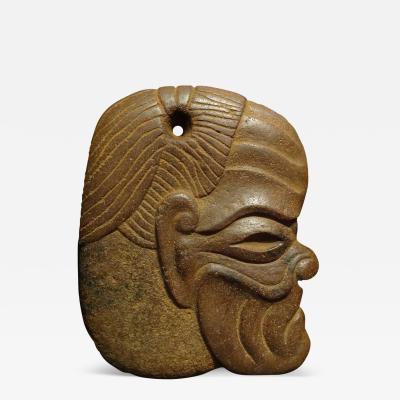

The couple then embarked on a connected path, collecting African ethnographic forms distinguished by their superior aesthetic quality and utilitarian roots. As Marc explains, “We started to collect forms, abstract, non-figural objects. We had done the figural thing, so we consciously avoided that.” To start their current collection, the Ginzbergs visited Colette Ghysels, a dealer in African ethnographic materials in Brussels, Belgium. Marc remembers, “Colette had three little rooms full of these objects. We looked around and asked prices, then asked to be left alone to talk. She came back, and we said, ‘This, this, and this we don’t want. We’ll take everything else.’ I suppose there were about seventy objects. She nearly fell through the floor.”

Over the past fifteen years the Ginzbergs’ collection, focusing on objects of adornment, containers, furniture, and weaponry, has grown tenfold. “These objects don’t have the spirituality of statues or masks, but they have a whole social tradition…a certain clan identity, and a function, in most cases,” Marc says. The collection was featured in a five city tour, "African Forms: Objects of Use and Beauty from the Ginzberg Collection," in 2004, and in Marc Ginzberg’s book, African Forms (2000).

Born in France, Denyse moved with her family, as they fled the Nazis, to Cuba in 1942. She grew up in Mexico, where she developed an appreciation for what she terms “folkloric art.” Marc, whose family founded Golodetz, the commodities trading firm to which he devoted his long career, was raised in Manhattan; his parents collected Chinese snuff bottles and other forms. “As in many such cases, as a couple collects together, each develops strengths,” Marc says, with a nod to Denyse’s sure judgment, naturally good eye, and quick decision making, and his own focus on study and contacts with curators and dealers, notably Mert Simpson in New York City and Colette Ghysels in Brussels.

“Collecting is just a matter of informed taste,” Marc says. “As a collector, you try to develop your own eye and consult people who know better than you do. You can have a favorite dealer, but it’s wise to work with more than one.”

The Ginzbergs have been active supporters of the National Museum of African Art, part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and were among the founders of the Museum for African Art in Queens, New York, slated to move to a permanent home on Museum Mile/Fifth Avenue and 110th Street in 2008. As a volunteer with the museum, Denyse organized trips to private collections and museums, such as Musée de L’Homme in Paris, the Musée Royal de l’Afrique in Tervuren, Belgium, and the Museum of Mankind in London. Interest in African art is different from most other fields of art, she remarks; it is characterized by a “small, tight group of collectors.”

The couple’s home was designed by architect Charles Forberg, son-in-law of Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus School. Sited on an inlet opening onto Long Island Sound, with water on two sides, it is a restrained, modernistic study in angles and light. Denyse designed its interiors, using a neutral palette of tree-bark beiges and natural textures of wood, glass, metal, and terra cotta as a soft descant to the strong, sure voices of the ethnographic pieces the Ginzbergs love.

Stepping into the entry, a visitor stands beneath the peaked glass skylight in a wide hallway that runs left to right along the length of the house’s central core. Straight ahead, floor-to-ceiling shelves flank the wide aperture leading to the step-down living room and frame a view of the sea foregrounded with rhododendron and native maples. The shelves in the entry and living room, totaling some 200 linear feet, display an array of objects so captivating they immediately divert attention from the water view. Earthenware ewers, gourd bowls and jars with incised decoration, beaded hats, woven lidded baskets, sculptural wooden stools and headrests, Orthodox crosses from Christian Ethiopia, tiny whistles of polished wood, hair combs of warm-hued ivory, iron trumpets, snuff bottles, spoons for measuring gold dust. Suddenly one understands Denyse Ginzberg’s coup de foudre upon seeing her first African object and the passion African art ignited in Marc Ginzberg, who has made it his lifelong avocation.

In evaluating the quality of ethnographic pieces, the Ginzbergs consider the patina, the age, and the form itself. “It’s a good rule to buy the best. You can rarely go wrong, even if you’ve overpaid. The gap between the top and second tiers in all areas of the art market is growing wider, and has been for decades,” Marc says. In the case of traditional African art, he explains, you might have four masks, good, better, best, and superlative, priced at $1,000, $10,000, $100,000, and more for the world’s finest examples. “In the case of forms, that hasn’t happened,” he notes. “A good one might cost $1,000, while a very good one is just $2,000. Why? Because the distinctions in quality have not yet been made. These are everyday objects, and one is like another. Eventually, you will see a drawing apart as in other fields.”

Many collectors of ethnographic art seek culturally “pure” examples. As Marc Ginzberg points out in his book, African Forms, “The shibboleth of African art connoisseurs is ‘pre-contact’: what came before the arrival of Europeans was authentic, valid, what came after, weak, corrupted. And innumerable examples can be given where this is so. But it also has to be remembered that there was always contact—we have simply learned to accept only some of it,” he says. “Take materials…the preponderance of beads in Africa are glass; some were imported 2,000 years ago, and by the eighteenth century shiploads were coming in. Similarly, cowrie shells are found on such ‘authentic’ objects as Kongo fetishes, Kuba cups, and Bambara masks. Cowries (the very word is Hindi) were always imported: some have been found in the Dynastic tombs of Egypt.” The same is also true of design. African craftsmen copied European manilla brass bracelets; the liturgical vestments of European missionaries in the Congo influenced the development of the Kuba cloth; and Madagascan and Kenyan grave markers derive from South Sea prototypes. “Collectors should not let old prejudices define their taste.”

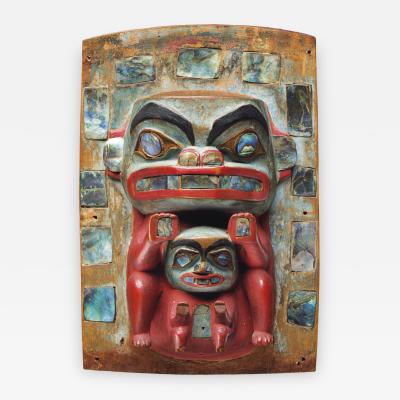

- “Ethiopian crosses divide into two groups, processional ones used as finials on a long staff and carried in parades and religious observances, and hand crosses carried by priests and used to bless the devout,” Marc Ginzberg says. Dating from the twelfth to the nineteenth centuries, some of the crosses in the Ginzberg collection are bronze, iron, and silver. The earliest is a solid bronze quatrefoil. An iron cross bears incised images of the Virgin Mary and the apostles. The latest, made of silver, is a late-nineteenth-century example from the high quality workshops that were operating at the time Marc says. “The quality produced in the twentieth century was not as good.” The round cross, he says, is a common type, which the couple has kept because it is so well executed. The crosses’ origins were Orthodox, a historic fact reflected in their decorative Coptic motifs. “Sometimes the crosses can be dated from their iconography,” he says, “In 1540, the Jesuits came in and the iconography changed. When Jesus is placed on the proper right of Mary, it’s pre-1527.”

By way of example in the Ginzbergs’ home, a Yuruba garment features a European cloth backing and diminutive glass beads, yet its rose-mustard-aqua coloration and a design, comprising rows of triangles, are distinctly African. A rectangular, incised metal cache Koran, hung as a pendant on a bead-embellished cord and containing a copy of the religious text, was made and worn by a member of the nomadic Tuareg group which migrates between Niger and Mauritania. A kotoko dwa or porcupine form Ashanti stool from Ghana is studded with rows of European brass upholstery tacks. And a wooden Kuba cup, collected by Henry Morton Stanley during one of his 1870s expeditions, recalls European exploration of Africa.

“If you look at the old dealers’ catalogues from about 1900, it’s mostly the ethnographic objects that were coming out of Africa,” Marc maintains. “At that point, the tribes were not selling statues and masks because they were religious in nature and part of their lives.” There was another reason for the preponderance of domestic objects on the market. As Marc explains in African Forms, “…the foreign visitor found the stool, the knife, the bracelet to be more graceful and esthetically accessible than the ‘distorted’ statue or ‘grotesque’ mask, and—not a small point—less overtly sexual.”

Age can be problematic in the context of ethnographic materials. “African art, generally speaking, is made of wood, which, of course, doesn’t last long,” Marc points out. “In general, the ages of pieces are not known. Most are attributed to the late nineteenth-early twentieth centuries. That’s true for seventy percent of it.” However, according to carbon 14 tests, one of the Ginzberg’s pieces, a life-sized Dogon figure is about 900 years old.

Determining the value and rarity of African forms can also be difficult, “When you’re dealing with a well-known form or type, you’re okay. If you’ve seen a lot, you know how good something is, or you go back to the books and make comparisons. When you’re confronted with an object you’ve never seen before…what you don’t know is whether that’s the end of it or not. If it’s unique or rare, its price should reflect that, but the next month, 1,400 could come out. So what should it cost?” By way of example, Ginzberg points to a semi-circular, leather covered, ceramic piece with a metal oval set into the top of its domed surface. Three such objects—it is unclear if they are wristbands, anklets, armbands, or archer’s guards—came out of Africa several years ago: Ginzberg had never seen the form before and hasn’t seen another since.

- In the master bedroom, a late-seventeenth century painted wooden chest from Tibet anchors an array of Asian objects that include a Japanese hearth hook and calligraphy box, coin silver spiral Indonesian ear or hat pendants, a Miao tribal coin silver necklace from southeast China, and a pair of ivory Naga bracelets from India. At right, a display niche, one of many incorporated into the design of the house, contains an assortment of Chinese snuff bottles collected in the 1930s and ’40s by Marc Ginzberg’s parents. The painting is by Colorado artist Gino Hollander (b. 1924).

One traditional stumbling block to collecting is, however, largely absent in the field of ethnographic forms. As Marc explains, “In forms, you don’t have the same fakery problem as in figurative art, where people do wonderful fakes and it takes years to know the difference. In forms, fakes are not as clever, and are much fewer. There are new Ethiopian crosses, for example, but not good fakes. It is problematic in African art, but not worse than in other forms of art,” Marc notes.

Ethiopian crosses are one of the Ginzbergs’ current interests. Used in that country’s Orthodox churches, and showing Coptic motifs, the metal crosses, Marc says, were “not much collected anyplace” when they caught the couple’s attention eight or so years ago. That is changing, Marc says, thanks in part to an exhibition of Ethiopian religious art in Jerusalem in 2000 to which the couple lent several pieces. Nonetheless, he says, medievalists have little interest in the crosses because they are not European, and objects of Christian origin do not generally appeal to collectors of African materials. Some of the crosses in the Ginzbergs’ collection date from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, while one shows the meticulous workmanship typical of the late nineteenth century.

A portion of the Ginzergs’ collection, already packed away, will be sold in Paris later this year. “After the auction, I would like to jump back in,” Marc says, citing the Ethiopian crosses and wood pieces from Asia, with age and provenance, as possible areas of concentration. “Snuff bottles from all over the world?” Denyse proposes playfully. Marc considers for a moment. “I wouldn’t mind,” he replies.

This article was originally published in the Spring 2007 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.