Patriotic Folk Art at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum

When Abby Aldrich Rockefeller loaned her folk art collection to the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in 1935, there was some question as to the appropriateness of showing primarily northern nineteenth-century nonacademic art in an eighteenth-century Virginia town. However, displayed in the Ludwell-Paradise House in the center of the village, restored to its colonial appearance by John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1926, the objects had relevance. Like the town itself, these pieces were a part of the nation’s past and worthy of being studied and celebrated. In 1957, when the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum got a permanent building on the outskirts of Colonial Williamsburg’s historic district, foundation president, Kenneth Chorley, said of its contents: “Much of this American folk art is naïve . . . but all of it is moving, and touched by the influences which shaped us as a people.” He described the museum as “another inviting doorway through which to step out of the Present into another and different time and place,” saying: “It, too, may help the Present to learn from the Past.”

- Fig. 1: Memorial to George Washington, attributed to Samuel Folwell and unidentified student of Mrs. Folwell’s. Philadelphia, Pa., ca. 1805. Silk, ink, and paint on silk. 26 x 21 inches. Inscriptions read, “Thy loss ever shall mourn” and “Sacred to the memory of the illustrious Washington.” Museum Purchase (1956.604).

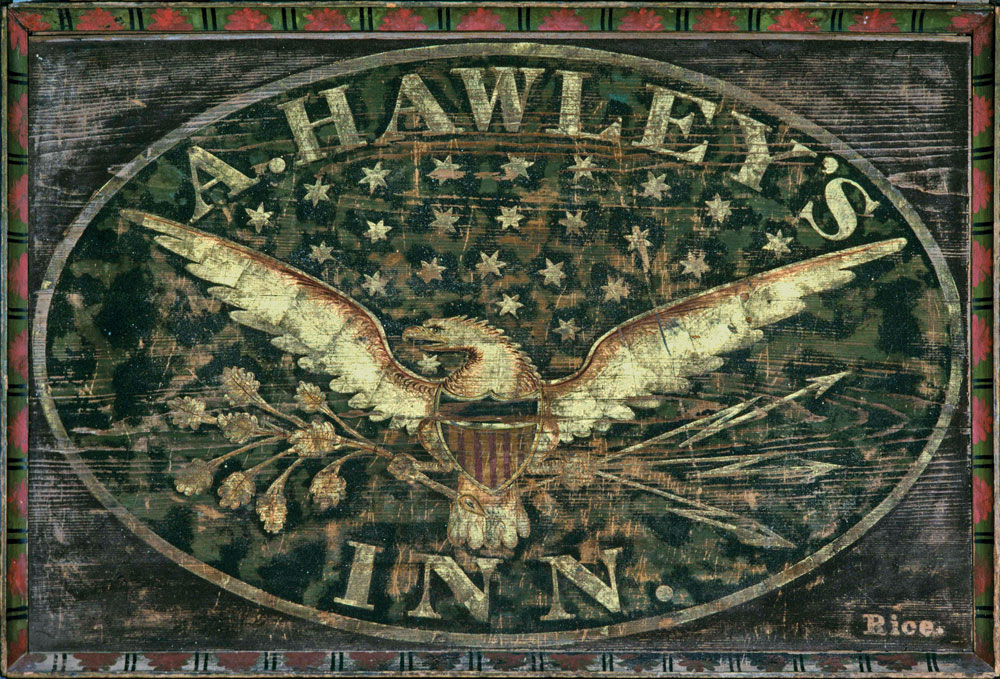

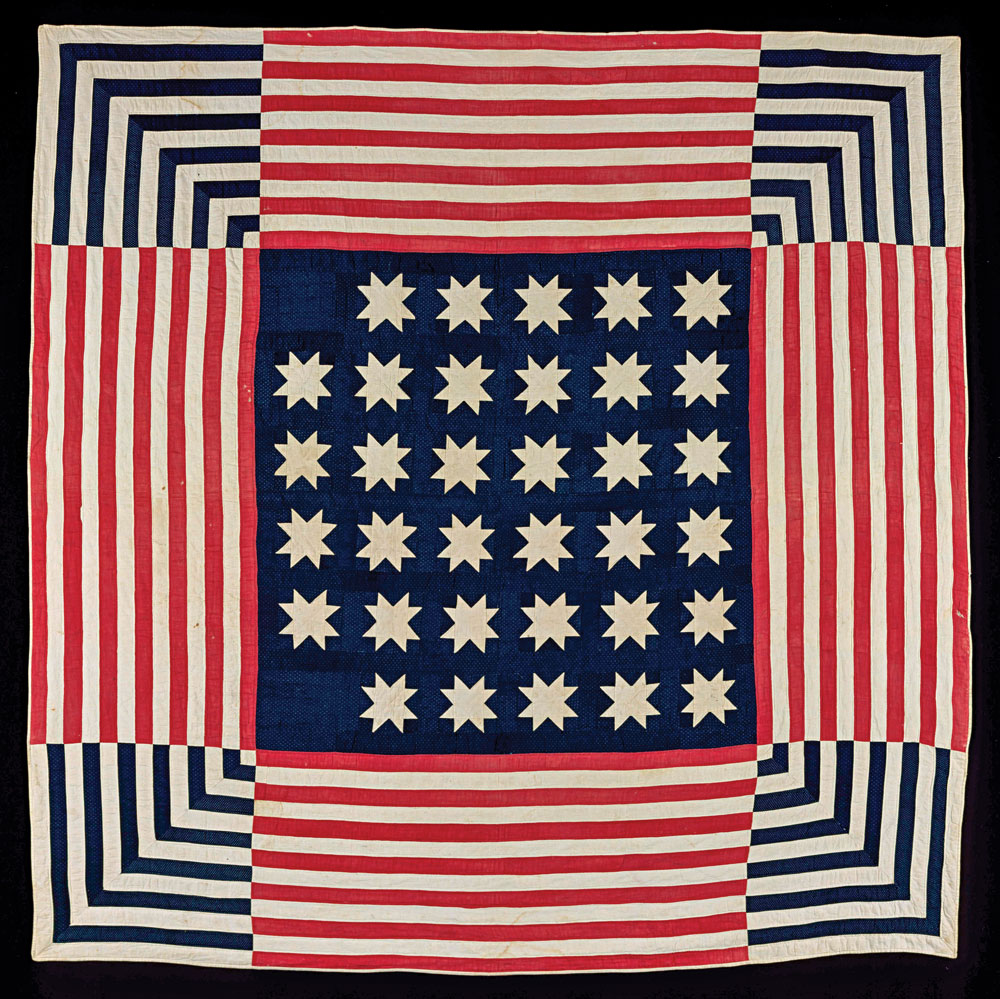

The AARFAM’s collection has grown since its inception sixty years ago, and today reflects what was important in America over the past two hundred years. Pride in the nation stands out as a major theme, beginning with the visual vocabulary associated with the American Revolution. The bald eagle, Lady Liberty, the Stars and Stripes, and George Washington all stood for America. Used officially on state seals, national coinage, and in government buildings, these symbols also found their way into everyday life, reflected in such items as tavern signs emblazoned with the bald eagle, Lady Liberty weathervanes, a George Washington-shaped stove, and quilts of red, white, and blue. These symbols had meaning both for the makers and users of the objects.

In 1799, the nation mourned the passing of their hero and first president, George Washington, with poems, music, and art dedicated to his memory. Female academies added mourning prints and designs to their needlework and painting classes. The Memorial to George Washington (Fig. 1), created around 1805 in Philadelphia, is attributed to professional painter Samuel Folwell and an unidentified student at his school, instructed in needlework by his wife, Elizabeth. In the image, the female mourner, dressed as Liberty, grasps a pole topped with the liberty cap, while leaning on a flower-draped memorial to Washington. Emerging from the clouds is a trumpeting cherub and an eagle, the emblems of the Order of the Cincinnati, of which Washington was a member. The needlework was likely hung in a place of pride in the student’s family home.

Representations of the first President lost none of their impact even decades after his death. Alonzo Blanchard patented his George Washington radiator parlor stove in 1843. The cast-iron figure of a toga-draped Washington radiated heat supplied by pipes connected to a stove in another room (Fig. 2). This popular design continued to be made for many years and by different manufacturers. Blanchard’s design is closely related to that of a marble statue made for the Massachusetts State Capitol and widely illustrated in the period.

Blanket chests provided large blank surfaces on which to express patriotic fervor. A chest from East Tennessee (Fig. 3) is evidence of traditional Germanic cabinetmaking practices. The painter incorporated traditional tulip motifs derived from his German heritage with the relatively new American symbol of the eagle, derived from the Great Seal of the United States.

Around the same time that the chest was made, William Rice, a skilled sign painter working in the Connecticut Valley, painted a sign for innkeeper Allen Hawley of Massachusetts (Fig. 4). Under a shower of stars, the spread-winger eagle holds the lightning bolts of war and the olive branch of peace. The reverse of the sign shows a chained lion. By coupling the end of British rule (the lion) with the beginning of independence (the eagle), Rice likely intended the sign to represent a celebration of America’s transition to nationhood. At almost five feet wide, the eagle was bound to attract passing travelers.

A more intimate patriotic expression is found in the double portrait of Mr. and Mrs. Elijah Robinson, attributed to Ruby Devol Finch and created around 1835 in Massachusetts (Fig. 5). This small watercolor features an eagle nestled between the oval likenesses of the couple. Like the Rice eagle, this one, with shield on chest, grasps the lightning bolts and olive branch, but Finch’s bird appears less fearsome, even a touch whimsical.

As indicated by the circa-1876 stamp in figure 6, a dairy farmer could signal his patriotic sentiments by impressing his butter with an eagle surrounded by stars. If his butter was to be sold, the patriotic impression might sway customers to his goods. This stamp is similar to a mass-produced example, but the carving is more crudely executed, suggesting that it was made by a person with simple woodworking skills. It was likely created during the Centennial, a time of heightened patriotic fervor.

A sand bottle combining the eagle with the American flag, and the date July 27, 1883, was the work of Andrew Clemens (Fig. 7). The obverse side of the bottle shows an arrangement of flowers and the message “From Nannie to Nellie.” Deaf since the age of five, Clemens was sent to boarding school but spent his summers at home in McGregor, Iowa, along the banks of the Mississippi, where he collected and sorted sand into forty different natural colors. He arranged the sand in small bottles with a fishhook or hickory stick to skillfully produce detailed images. Clemens sold his amazing sand art at a local grocery store for about five to seven dollars a bottle. He produced hundreds of these works of art, but because of their fragile nature few survive today.

Although some artists worked the flag into their compositions, many others used the elements of it in a variety of ways that still evoked national pride. Just the words “stars and stripes” or “red, white and blue” can stir patriotic sentiments. And perhaps an even greater impact is achieved by visually representing those words. The quilt in figure 8 is striking for its strong use of color and pattern. There is no mistaking its message. The quilt is called Patriotic Stars and was similar to a published pattern that appeared in the July 1861 issue of Peterson’s Magazine, and intended to inspire quilters to express their Union sympathies during the Civil War. Just as the stars on the flag do, the thirty-four stars in the center field represent the number of states in the Union, including those that had seceded at the beginning of the war.

In a similar way, a barber pole from around 1900 uses white stripes and white stars on a blue ground to great visual effect (Fig. 9). The gold-painted ball on the top is reminiscent of the finial on a flagpole. The addition of the stars and the color blue to the traditional red and white of the barber’s pole give this seven-feet-tall sign an emphatic patriotic slant.

In a more subtle expression of national pride, the paint scheme of the carved wooden figure of Columbia matched those of the quilt and pole (Figs. 10, 10a). Derived from the name of Christopher Columbus, Columbia was the poetic name often given to the United States of America and the female personification of the country, also sometimes called the “Goddess of Liberty.” This carving was likely based on cast zinc figures made in New York. Both the wood and zinc versions probably were intended to be carried in parades and displayed in public spaces, where they reminded Americans of their commitment to liberty. Columbia features several patriotic motifs: a liberty cap, a laurel wreath, a federal shield, a scabbard, and a now-missing sword.

When the Statue of Liberty was dedicated in New York City’s harbor on October 28, 1886, it created a vast outpouring of excitement and national pride. The copper statue, a gift to the United States from the people of France, was designed by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and built by Gustave Eiffel. Weathervane manufacturers capitalized by executing scaled-down versions, undeterred by the fact that the figure has insufficient horizontal elements to be turned effectively by the wind (Fig. 11). To counteract this defect, firms mounted the figure on an arrow having a weighted point and broad feathers.

The AARFAM’s collection holds many more patriotic treasures but it seems fitting to sum up this brief survey with Miss Liberty (Fig. 12), who gracefully offers a drink to the mighty bald eagle, while the flag flies in the background topped with the liberty cap. The unidentified painter was just one of the artists who throughout the nation’s history, have expressed their love of country in objects that still speak to us today.

-----

Jan Gilliam is the manager of exhibitions and associate curator of toys at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum (AARFAM).

All images courtesy Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum.

Read related articles: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and Her Folk Art Museum and A Touch of Whimsy in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum.