Piratenim: The Story of an Extraordinary Historic Ship's Figurehead

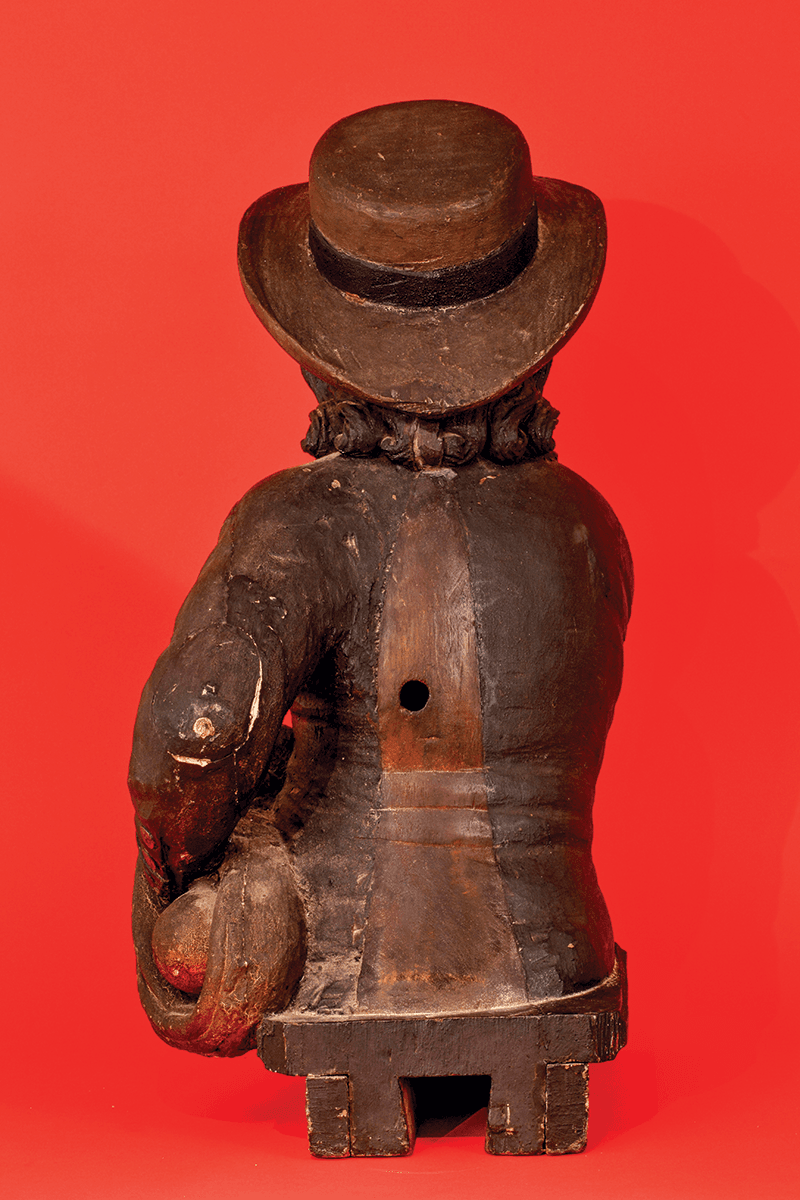

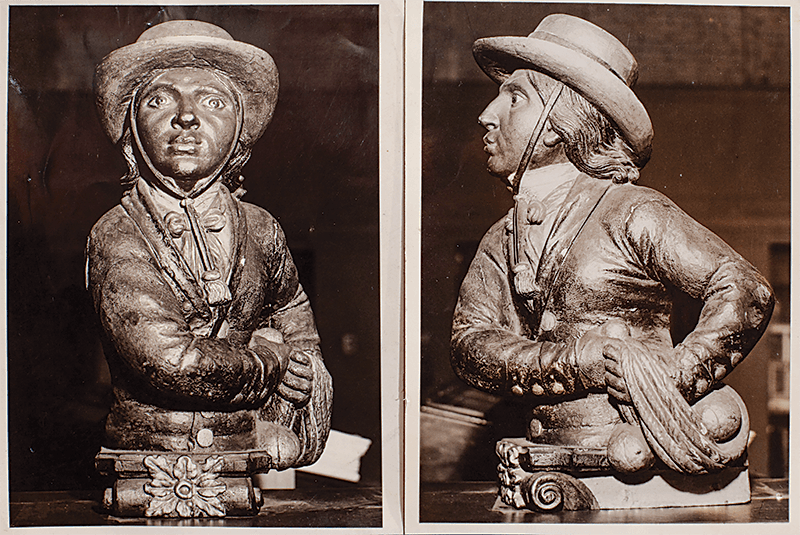

In 1944, Britain was still very much at war. Vast areas of Europe lay in ruins, with even more destruction to follow before final victory. Despite this atmosphere of uncertainty, Vivian Collett, a local city councillor, enjoyed his walks around the cathedral city of Worcester, where he visited the many small antiquarian bookshops and antique shops dotted around the periphery of the city’s center. One day, peering into the window of one such shop, he entered, and within moments, became the latest in a line of owners of a small but enchanting ship’s figurehead. Carved in the form of a handsome young South American gaucho (Fig. 1), the figure was dressed in a jacket and white shirt with a red scarf, and held a set of boleadoras, a throwing weapon used to subjugate cattle or other animals. The word Piratenim was emblazoned on his wide-brimmed hat (Fig. 2). Age had patinated the surface of the carving with a rich crackalured texture (Fig. 3).

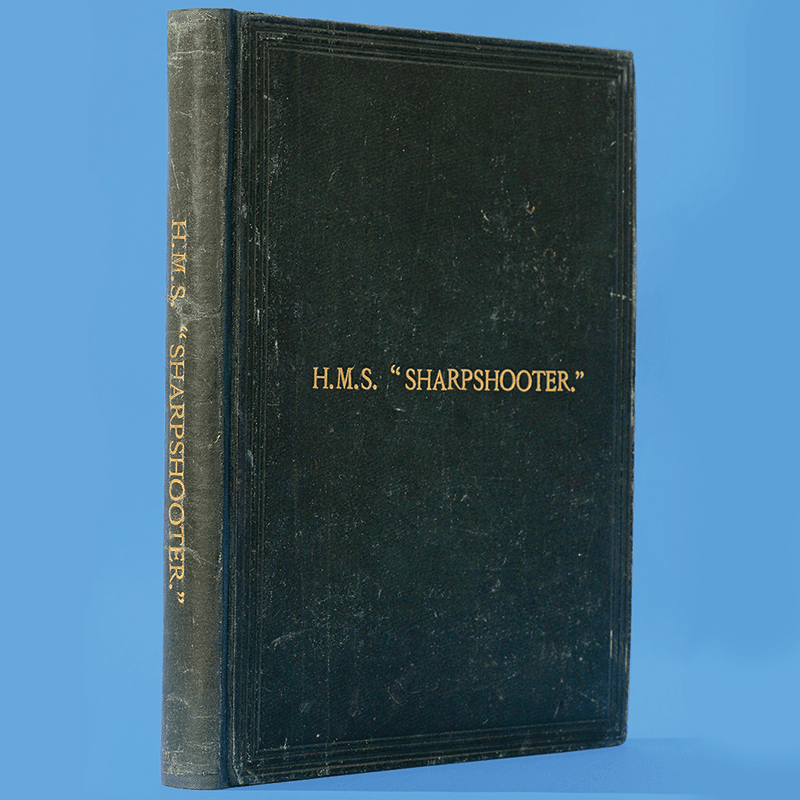

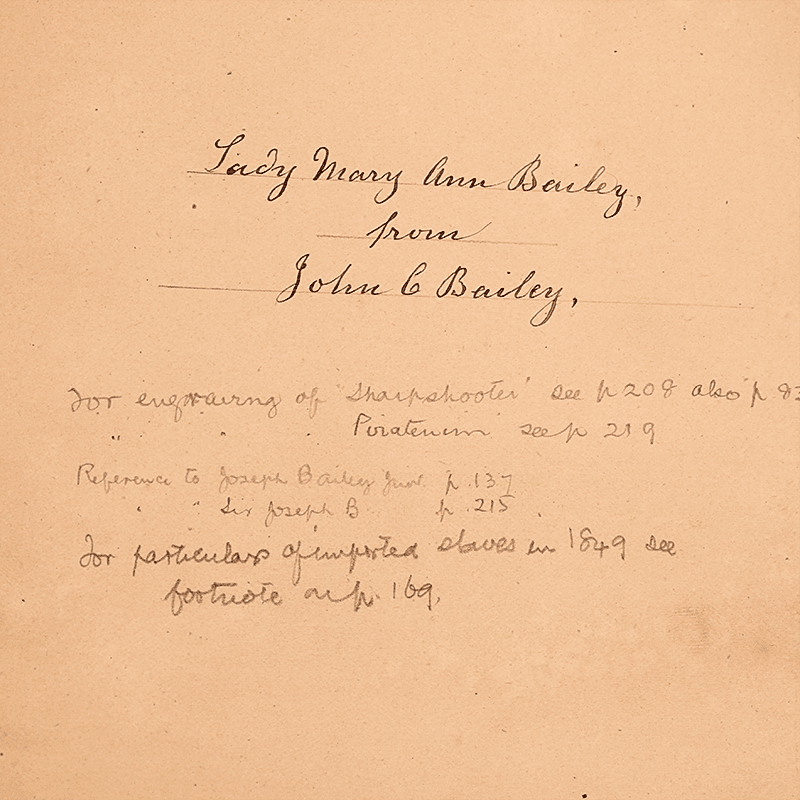

Together with the figurehead, Collett bought a small book entitled H.M.S. Sharpshooter (Fig. 4), which he soon discovered threw light on the figurehead’s fascinating story. Additional history was provided a year later when, in January 1945, The Mariners Mirror: House Journal of the British Society for Nautical Research (vol. 31, no. 1) published “The last of the Brazilian Slavers 1851,” by Averil Mackenzie-Grieve. Illustrated were two black-and-white images of the Piratenim’s figurehead, detailing its history and survival (Fig. 5).

H.M.S. Sharpshooter, written and privately published by Lieutenant John Crawshay Bailey, is a narrative of Bailey’s early naval career and the exploits of his vessel, the Sharpshooter, while stationed off the east coast of South America with a mandate to stop the slave trade.1 The United Kingdom had outlawed slaving some forty years previously, but it was still endemic. The sheer number of slaves transported to Brazil was a moral and financial concern for England. Pressure from religious reformers against the continuing trade in Brazil was coupled with the negative effects the large number of slaves working in the Brazilian sugar industry were having on England’s sugar profits in the West Indies. Together with three other ships, the Cormorant, Plumper, and Locust, Bailey’s ship was authorised to seize any slave ships, free the slaves, apprehend the crew, and send the vessel to the nearest British port or destroy it.

Within a week of joining the squadron, the Sharpshooter had seized two slave ships, the Malteza and the Conceicao, and by September 1850, she had captured her fifth prize, a small cutter called the Amelia carrying seventy-four slaves. By the end of the year, the Sharpshooter had made nine captures and freed many hundreds of slaves. It’s safe to assume that each of these captured ships carried on its bow some kind of figurehead, a talisman of sorts offering security to its passengers and providing identification to other ships.

Toward the end of June 1851 after some time in port, Bailey and the Sharpshooter took up station off the coast of Brazil. It was here Bailey captured the Piratenim. Bailey describes in great detail the capture of the vessel and noted the figurehead was missing; he initially surmised it had been torn away at sea. Once on board, the crew, passengers, and slaves were sorted out and a full inspection of the vessel took place, with surprising results. Bailey recorded the following:

The brig was taken possession of, and in the course of her examination the missing figurehead was found stowed away in the hold. It was a peculiar one, and for that reason had been unshipped, lest it might lead to the vessel’s identification. It represents a Gaucho, or Bolero who catch the wild cattle and horses of the Pampas by hurling a ball, attached to a long line [boleadoras], round the animal’s horns or forelegs. Whereon the huntsman’s horse, to whose saddle the other end of the line is secured, stops dead short, and so throws the pursued animal to the ground. This figurehead, together with some slave whips and drinking tubes found on board the Piratenim, are now in the possession of Sir Joseph Bailey.

Bailey’s description of the boleadoras as carved into the figurehead is of note. It seems quite plausible that the roping tool represented cattle ranching, one of the several activities for which the large numbers of slaves brought to Brazil were used, along with sugar and coffee production and mining. The carved boleadoras further reinforce the nature of the symbolic identification of the Piratenim as a slave ship, and provides a reason for the captain and crew’s interest in hiding the figurehead when entering waters they knew were patrolled by the English. Bailey’s actions in seizing the ship and human cargo, however, were later challenged in court, as reported in the article “English Measures for Suppressing the Slave Trade” (Daily News, September 12th, 1851):

Our Rio correspondent writes as follows—Rio De Janeiro Aug 13: “The first case which I have to report is the capture and destruction of the brig Piratinim, and the facts of the case I will state in as few words as possible, leaving you to form your own opinion as to the legality of the capture. The Piratinim dailed from Bahia with a cargo of 4,000 alqueires of salt, 37 packages of earthenware and china, and a few barrels of sherry and Madeira wines, Her passengers were the Senhor Leitao, the owner of a large sugar estate near Cawpos, and 97 slaves belonging to the same gentleman, it is necessary here to remark, that about one-third of the number were mulattos, and that all the others were creoles, and speaking the Portuguese language. Each slave was provided with a passport from the police authorities of Bahia, had been duly despatched from that port, and had embarked publicly, and during the day time; in short, the cargo of the Piratinim was in all respects a legal one, and she pursued her voyage with all the confidence and fancies security of an honest trader.

- Fig 4: This book, written and published by Lieutenant John Crawshay Bailey, was personally inscribed to his mother, Lady Mary Ann Bailey. Image courtesy of Alan Granby and Janice Hyland.

The fact that the figurehead of the Piratenim had been removed from the bow and hidden is pivotal to its survival. Without this intentional action, like countless thousands of other figureheads, this historically significant object would have undoubtedly been destroyed with its host vessel or rotted away at the bottom of the ocean. The ability to link it to a specific vessel and know its associated provenance makes this figurehead an extraordinarily rare artifact of history.

John Bailey’s reason for seizing the figurehead was likely as a souvenir of his conquest, though he may also have appreciated the aesthetic and possible historic significance of this particular carving. Returning to the United Kingdom, he placed it in the care of his father, Sir Joseph Bailey, first Baron Glanusk, of Glanusk Park, Breconshire, Wales. For almost one hundred years it was kept safe at Glanusk Park. When Glanusk Park was requisition by the army during World War II, it can be assumed that its contents were sold to local dealers in Worcestershire, with the figurehead winding up in the city of Worcester, just fifty-eight miles north of the Park; the mansion house was demolished in 1952. After Vivian Collett bought the figurehead, it remained with his own family for seventy years, until Alan Granby and Janice Hyland became the most recent owners and custodians of this truly remarkable survivor from the history of slavery.

This Important Figurehead is now on sale. To inquire about this piece, please visit Hyland Granby's InCollect page by CLICKING HERE.

Richard Hunter is a figurehead historian working in the United Kingdom and is owner of The Hunter Figurehead Archives, the world’s largest private figurehead related archives (www.figureheads.co.uk).

This article was originally published in the Summer 2015 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available on afamag.com. Antiques & Fine Art, AFAmag, AFAnews, and AFA Publishing are affiliated with InCollect.com.