Pueblo Dynasties: Master Potters from Matriarchs to Contemporaries

|

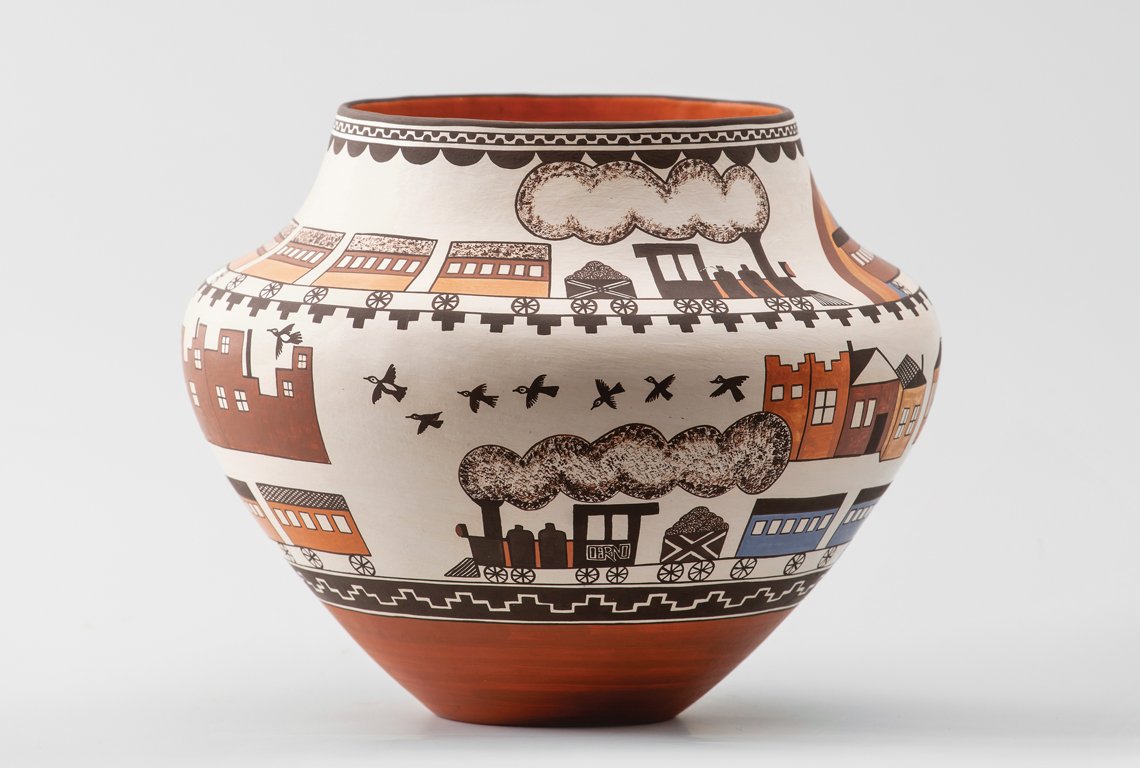

Fig. 1: Barbara Cerno (Hopi/Acoma, born 1951) and Joseph Cerno Sr. (Acoma, born 1947), Pictorial Train Olla, 2011. Earthenware, 8⅜ x 10 (diam.) in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2011.63.1). |

| |

Fig. 2: Attributed to Nampeyo of Hano (Hopi-Tewa, ca. 1856–1942), Bowl with Mission Design, ca. 1905. Earthenware, 3 x 10 (diam.) in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2015.21.1). |

American Indians of the Southwest began to make pottery at least two thousand years ago, passing their skills from generation to generation, a tradition that continues to this day. Geographic variations in clay, along with local preferences for certain designs and shapes, meant that recognizable styles became associated with certain villages, which the Spanish called pueblos. When the railroad began to bring visitors to the Southwest in the late nineteenth century, it spurred a market for pottery as art. Makers started to sign their work, and individual potters became known and their pieces collected. These artists drew inspiration from their ancestors and built upon established traditions. In September, the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento opened an exhibition of more than two hundred ceramic vessels and sculptures by premier pueblo potters of New Mexico and Arizona. Pueblo Dynasties: Master Potters from Matriarchs to Contemporaries focuses on the legendary matriarchs and their artistically adventuresome descendants, whose works have become increasingly elaborate, detailed, personal, and even political, over time.

| |

Fig. 3: Dextra Quotskuyva Nampeyo (Hopi-Tewa, 1928–2019), Sherd Pot, n.d. Earthenware, 3½ x 12 (diam.) in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2017.110.18). |

The Crocker’s overall ceramics collection is one of the largest public collections in the United States and includes more than 5,000 examples from the Americas, Europe, and Asia. The institution’s American Indian pottery collection expanded dramatically in recent years through the generosity of the late Dr. Loren G. Lipson, who sponsored the acquisition of signature works by many of the most important American Indian potters, both historic and contemporary. The collection started in 2011 with a train vessel by Acoma potter Joseph Cerno (born 1947), who in this piece and others collaborated with his wife, Barbara (born 1951) (Fig. 1). The train motif was an especially appropriate place to begin, as the museum’s founder, E. B. Crocker, was instrumental in building the Transcontinental Railroad. The Cernos, along with their son Joseph Jr. (born 1972), are also known for producing large parrot pots and seed jars, the latter rendered with complex historical and natural motifs.

Though the names of early potters have been lost to history, three of today’s best-known ceramic families of the Southwest—Nampeyo, who are Hopi-Tewa; Martinez, of San Ildefonso; and Tafoya, from Santa Clara—are represented by up to six generations of ceramists. The most illustrious line of Hopi-Tewa potters began with a woman named Nampeyo (ca. 1856–1942), who was born on First Mesa in Hano, or Tewa Village, located in the eastern part of the Hopi reservation in northeastern Arizona. Tewa-speaking people of northern New Mexico relocated there to escape the Spanish after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Nampeyo learned the fundamentals of pottery-making from her paternal Hopi grandmother and her Tewa mother. After seeing prehistoric pieces excavated from the village of Sikyátki by anthropologist Jesse Fewkes in 1895, she began to adapt old designs and, in so doing, garnered a reputation (Fig. 2). By selling these pieces to traders, who distributed them widely, and by teaching others in her village her techniques, she started the Sikyátki Revival, which continues to this day. Nampeyo, like other potters to date, did not sign her pieces, as the practice was traditionally viewed as according too much attention to an individual rather than the community, although her daughters and descendants did.

|

Fig. 4: Rondina Huma (Hopi-Tewa, born 1947), Jar with Sherd Design, n.d. Earthenware, 4¼ x 8¼ (diam.) in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2015.21.8). |

.jpg) |

Fig. 5: Maria Martinez (San Ildefonso, 1887–1980) and Julian Martinez (San Ildefonso, ca. 1885–1943), Bowl with Checkerboard and Kiva Step Designs, before 1930. Earthenware, 5⅝ x 12⅛ (diam.) in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2015.71.58). |

When Nampeyo began to lose her sight in 1920, she continued to make coiled pots but relied on her three daughters—Annie Healing Nampeyo (1884–1968), Nellie Douma Nampeyo (1896–1978), and Fannie Polacca Nampeyo (1900–1987)—to decorate and fire them. They, in turn, passed their skills to their children. Pueblo Dynasties includes numerous examples by the senior Nampeyo and her descendants, who are collectively renowned for their finely wrought polychrome designs founded in tradition and individually interpreted by each potter. The collection is especially strong in work by descendants of Annie Healing, who taught her daughter Rachel Namingha Nampeyo (1903–1985), who in turn shared her skills with Dextra Quotskuyva Nampeyo (1928–2019). Dextra, an important mentor to other potters and artists, is represented by a large and elaborate vessel ornamented with depictions of pottery sherds (Fig. 3). Dextra’s daughter, Hisi Quotskuyva Nampeyo (born 1964), is also a potter, and Dextra’s son, Dan Namingha (born 1950), is a painter and sculptor. Several of their first cousins are talented ceramists, two of the most significant being Steve Lucas (born 1955) and Les Namingha (born 1967), both of whom learned from Dextra.

| .jpg) | |

Left: Fig. 6: Barbara Gonzales (San Ildefonso, born 1947), Seed Jar, n.d. Earthenware, with inset turquoise and coral, 7¼ x 13½ (diam.) in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. Right: Fig. 7: Cavan Gonzales (San Ildefonso, born 1970), Jar, n.d. Earthenware, 12¾ x 12¾ (diam.) in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2017.110.8). | ||

| |

Fig. 8: Dora Tse-Pe (San Ildefonso/Zia, born 1939), Jar with Avanyu, 1992. Earthenware, 8½ x 9¼ (diam.) in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2017.79). |

Other Hopi-Tewa potters include Paqua Naha, called Frog Woman (ca. 1890–1955), who near the end of her life developed a white-ware style that her daughter, Joy Navasie, second Frog Woman (1919–2012), popularized. Grace Chapella (1874–1980) learned her skills from her mother and, significantly, her neighbor, Nampeyo. As with Nampeyo, she derived motifs from historic sherds, and is most recognized for her butterfly or moth designs, which became inextricably identified with the Chapella family. Rondina Huma (born 1947), who grew up in the Hopi village of Polacca, is one of the most famous contemporary potters to appropriate Sikyátki sherd designs, turning them into geometric patterns of extraordinary complexity (Fig. 4).

From a pueblo north of Santa Fe, San Ildefonso potters are celebrated for their elegant black-on-black pottery. Maria Montoya Martinez (1887–1980) popularized the black-ware style (Fig. 5) but her earliest pieces were polychromes, as were those made by her uncle and aunt, Florentino Montoya (1858–1918) and Martina Vigil (1856–1916), who taught her. Martinez was the first potter to consistently sign her pieces, beginning in 1923. She collaborated with her husband Julian (ca. 1885–1943), son Popovi Da (1922–1971), and daughter-in-law Santana Roybal (1909–2002). She also fostered the talent of grandson Tony Da (1940–2008), acclaimed for his innovative designs and meticulous technique.

The family line continues through multiple direct and indirect descendants. Great-granddaughter Barbara Gonzales (born 1947), for instance, combines black-on-black decoration with sgraffito (incising) and inset stones, often incorporating spiders, a symbol of good luck (Fig. 6). Gonzales’s sons also make pottery, including Cavan Gonzales (born 1970), who returned to making boldly decorated polychromes (Fig. 7).

|

Fig. 9: Linda Cain (Santa Clara, born 1949), Jar, 1992. Earthenware, 8 x 5 (diam.) inches. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2016.79); Autumn Borts-Medlock (Santa Clara, born 1967), Dragonfly Pot, n.d. Earthenware, 13 x 13 inches. Crocker Art Museum purchase, with funds provided by Loren G. Lipson, M.D., and the Martha G. and Robert G. West Fund (2018.62); Tammy Garcia (Santa Clara, born 1969), Northwest Native Bear, 1999. Earthenware, 12 x 10 (diam.) inches. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2017.64); Christina Naranjo (Santa Clara, 1891–1980) and Mary Cain (Santa Clara, 1915–2010), Vessel with Avanyu, n.d. Earthenware, 13½ x 9 (diam.) inches. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2014.1.22). |

.jpg) | .jpg) | |

| Left: Fig. 10: Nathan Youngblood (Santa Clara, born 1954), Carved Black Egg, 1998. Earthenware, 5½ x 7½ in. Crocker Art Museum purchase, with funds provided by the Martha G. and Robert G. West Fund; Aj Watson; Janet Mohle-Boetani, M.D., and Mark Manasse; and the F. M. Rowles Fund (2016.105). Right: Fig. 11: Nancy Youngblood (Santa Clara, born 1955), Vessel with Avanyu, n.d. Earthenware, 6 x 14 (diam.) in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2017.29). | ||

Dora Tse-Pe (born 1939) uses subtle black and brown effects and inset turquoise or coral to decorate her pots (Fig. 8). Born at Zia Pueblo, she learned pottery first from her mother, Candelaria Gachupin (1908–1997), and then broadened her skills under the tutelage of Rose Gonzales (1900–1989) of San Ildefonso, after she married Gonzales’s son, potter Johnny “Tse-Pe” Gonzales (1940–2000). Rose Gonzales was the innovator of carved pottery at San Ildefonso, having discovered the tradition on an ancient sherd. She passed her knowledge to Dora and Tse-Pe.

.jpg) | |

Fig. 12: Jody Naranjo (Santa Clara, born 1969), Large Square Jar with 194 Figures, 2003. Earthenware, 15½ x 10 in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2016.97). |

Deeply carved pottery is today primarily associated with Santa Clara Pueblo potters, based northwest of Santa Fe (Fig. 9). There, Sara Fina Tafoya (ca. 1863–1949) started a family line that includes many of today’s most respected makers. Tafoya is known for large, elegant storage jars, most of which are undecorated, though some of her pieces include scalloped rims and impressed or carved designs. Her talents continued through three of her children: Christina Naranjo (1891–1980), Camilio Tafoya (1902–1995), and Margaret Tafoya (1904–2001), all of whom practiced a style of deep carving that established the family’s recognizable aesthetic.

There are now dozens of Tafoya family descendants. Christina Naranjo’s daughter Mary Cain (1915–2010) and granddaughter Linda Cain (born 1949) followed in her footsteps, just two among many of her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren to work in clay (see figure 9). Linda Cain’s daughters are the esteemed sisters Autumn Borts-Medlock (born 1967) and Tammy Garcia (born 1969), the latter represented by an unusual piece featuring a Pacific Northwest design. Camilio Tafoya’s children include potters Joseph Lonewolf (1932–2014) and Grace Medicine Flower (born 1938), both known for their elaborate sgraffito decorations, Medicine Flower often combining hers with deeply carved forms. Margaret Tafoya had eight children, all potters, including Mela Youngblood (1931–1991), whose own children, Nathan Youngblood (born 1954) (Fig. 10) and Nancy Youngblood (born 1955) (Fig. 11), are celebrated for their extraordinary forms and carving. A cousin, Linda Tafoya-Sanchez (born 1962), daughter of potter Lee Tafoya (1926–1996), frequently combines high polish with sparkling micaceous clay. Only recently recognized for its beauty, micaceous clay was long used to make cooking pots, the minerals helping to distribute heat and add durability.

.jpg) |

Fig. 13: Roxanne Swentzell (Santa Clara, born 1962), Looking for Root Rot, 2004. Earthenware, 12 x 12¾ x 16¼ in. Crocker Art Museum; Gift of Loren G. Lipson, M.D. (2015.71.59). |

Known for vessels with stylized animal motifs and, sometimes, political commentary, Santa Clara Pueblo potter Jody Folwell (born 1942) pushes aesthetic and thematic boundaries, as does her daughter Susan Folwell (born 1970) and nieces Roxanne Swentzell (born 1962) and Jody Naranjo (born 1969), all of whom extend and challenge traditions. Naranjo’s pots are made using traditional methods—digging clay, processing it, using coils to build forms, and pit firing—while her painted and carved decorations are decidedly contemporary. She is best known for her stylized “pueblo girls,” one ambitious vessel featuring one hundred and ninety-four of them, each holding a pot (Fig. 12). Swentzell, in turn, uses clay to make figurative sculpture, most often of women, the pieces ranging from humorous to poignantly introspective. The coarse clay used in Looking for Root Rot indicates that the piece was made while the artist was living in Hawaii. The figure’s expression suggests longing, and the title conveys the artist’s fear of losing her identity in a place so far from home (Fig. 13).

Subsequent generations of Southwest potters will, no doubt, be equally innovative, contributing to and expanding upon the accomplishments of their families and, in some cases, establishing new dynasties of their own.

|

Pueblo Dynasties: Master Potters from Matriarchs to Contemporaries runs through January 5, 2020. For information, call 916.808.7000 or visit www.crockerart.org.

Scott A. Shields, Ph.D. is associate director and chief curator at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, California. He is curator of Pueblo Dynasties.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2019 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.