A Selection of Discoveries Come to Light

Rediscovering the Muhlenberg Family

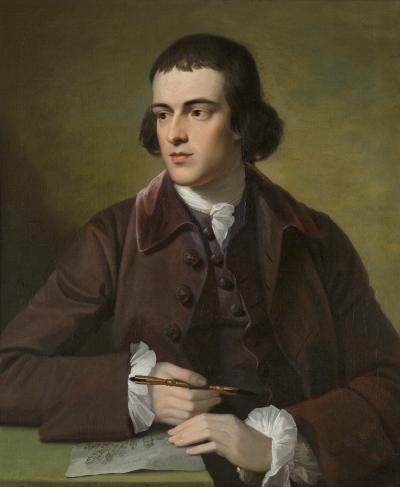

Several major discoveries have recently come to light that offer important new insights on the Muhlenbergs—one of the most influential German-American families in U.S. history. Patriarch Henry Melchior Muhlenberg (1711–1787) immigrated in 1742 and settled in Trappe, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, where he devoted the rest of his life to establishing the Lutheran Church in America. His oldest son, Peter, served as a general in the American Revolution, while the second son, Frederick, was the first Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives and first Signer of the Bill of Rights. The youngest son, Henry Jr., was a renowned botanist nicknamed the “American Linnaeus” and a life-long Lutheran minister.

|  | |

| Fig. 1:Portrait of Catharine Muhlenberg (1750–1835), attributed to Joseph Wright (1756–1793), New York, ca. 1790. Oil on canvas. H. 49, W. 37¾ inches. Collection of the Blake Family. Photo by Gavin Ashworth. | Fig. 3: Sugar bowl owned by Frederick and Catharine Muhlenberg, made by Christian Wiltberger (1766–1851), Philadelphia, ca. 1790. H. 9½ inches. The Speaker’s House. Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

|

| Fig. 2: The Speaker’s House, home of Frederick and Catharine Muhlenberg, Trappe, Pa. Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

In 1910, Muhlenberg descendants published a genealogy, the Muhlenberg Album, illustrated with black-and-white photographs of family heirlooms. Many of these objects remain in the family or are now in museum collections, but some disappeared. Such was the case with a portrait of Catharine Muhlenberg, painted by Joseph Wright about the same time as his 1790 portrait of her husband Frederick Muhlenberg, until persistent detective work finally unearthed it (Fig. 1). Both portraits are identified in the Muhlenberg Album as the property of Mrs. George Brooke I of Birdsboro, Pennsylvania. Born Mary Baldwin Irwin, she died in 1910, and her husband in 1912. The portrait of Frederick descended through their son Edward’s line and in 1974 was donated to the National Portrait Gallery.1 But this line of the family knew nothing of Catharine’s portrait. When Monroe Fabian wrote a catalogue raisonné on Joseph Wright, he noted that the original portrait was probably destroyed in a 1917 house fire. In his research notes, however, he theorized the portrait might be in the possession of a Mrs. Samuel Guiberson of Dallas, Texas.2

More sleuthing identified Ms. Guiberson as Elizabeth Muhlenberg Brooke Blake, the only child of George Brooke II; identification had been hampered by numerous name changes as a result of five marriages over the course of her 100-year life. The portrait did not fit in with her contemporary art collection and, after her death in 2016, it was located in the attic of her Newport summer house. Thanks to the generosity of her sons, Tom and Doug Blake, the portrait has now returned to Trappe. It will ultimately be displayed in the home of Frederick and Catharine Muhlenberg, now known as the Speaker’s House, after the conclusion of restoration work on the house (Fig. 2).3

|

| Fig. 4: Card table, attributed to Daniel Rhein (1778–1868), Reading, Berks County, Pa., ca. 1810. Mahogany, satinwood, and mixed-wood inlay with tulip poplar and white pine. H. 30, W. 36 ½ , D. 17¾ inches. Private collection. Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

|  | |

| Fig. 4a: Detail of inlay on the card table illustrated in figure 4. Photo by Gavin Ashworth. | Fig. 5: Chest-on-chest made for the Muhlenberg family, Philadelphia, Pa., ca. 1760–75. Mahogany, tulip poplar, cedar, brass. H. 93, W. 44¼, D. 23 inches. Wunsch Americana Foundation. Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

The 1910 Muhlenberg Album also includes an image of five camp cups inscribed “PM” for Peter Muhlenberg and a tea set bearing the monogram “FCM” for Frederick and Catharine Muhlenberg, including a large urn-shape sugar bowl with pierced rim, helmet-form silver creamer, and slop bowl; the five cups remain in the family but no trace of the sugar bowl or its companion pieces was found among living descendants. Then along came the Roy and Ruth Nutt sale at Sotheby’s in 2015. Tucked away in this vast collection of American silver was the Muhlenberg sugar bowl, which by then had lost its family history (Fig. 3).4 The sugar bowl was acquired on behalf of The Speaker’s House organization, and is now home again in Trappe.

Stamped on the foot rim is the mark of Christian Wiltberger (1766–1851), a leading Philadelphia silversmith in the late 1700s. Given their shared German heritage, it is likely no coincidence that the Muhlenbergs hired Wiltberger. Sugar was particularly meaningful to Frederick and Catharine Muhlenberg. Her father, David Schaeffer Sr., was a sugar refiner or “baker” in Philadelphia. After his death in 1787, Catharine and her siblings became part owners of the refinery. Frederick Muhlenberg soon bought out his in-laws and went into partnership with Jacob Lawerswyler. Plagued by a string of bad luck including the loss of a ship to pirates—who also kidnapped and ransomed his son-in-law, John M. Irwin, who was on board—Frederick’s sugar venture ultimately failed. Nonetheless, sugar was a valuable commodity mentioned frequently in Muhlenberg family papers and sold in Frederick’s general store, adjacent to his house in Trappe.

|

| Fig. 5a: Detail of shell carving on the chest-on-chest illustrated in figure 5. Photo by Gavin Ashworth. |

Another long-lost object illustrated in the 1910 Muhlenberg Album that has recently come to light is an inlaid card table owned by Maria Salome (Sally) Muhlenberg (1766–1827) and her husband Matthias Richards Jr. (Figs. 4, 4a). After the card table surfaced at auction in 2012, careful study of its distinctive bellflower inlay enabled a firm attribution to the Reading, Pennsylvania, cabinetmaker Daniel Rhein, based on a signed clock case with identical inlay. The youngest daughter of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg and his wife Anna Maria Weiser, Sally married Matthias Richards Jr. in 1782. They lived in New Hanover, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, before moving to Reading. A saddle maker by profession, Richards served in the Revolution, and became a merchant, a Berks County judge, and U.S. Congressman.

By the time of his death in 1830, Richards had accumulated household furnishings worth more than $730, including two card tables worth $10.5 Of particular note is the card table’s curvaceous top—a serpentine with ovolo ends—heretofore identified on only a tiny fraction of American card tables made in only a few areas, namely Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Newburyport, and now Reading, Pennsylvania.6

By far the most impressive piece of Muhlenberg family furniture yet to be uncovered, this mahogany chest-on-chest was consigned to auction in 2015 and subsequently acquired by the Wunsch Americana Foundation (Figs. 5, 5a). It survived in largely original condition—including a spectacular carved shell—but suffered from having replaced brasses, finials, and plinths; poor old repairs to the drawer fronts; and missing appliqué carving in the pediment. Restored by furniture conservator Keith Lackman and woodcarvers Rob McCullough and Fred Hoover, clear witness marks enabled the original brasses to be accurately replaced, while the holes left by later brasses were expertly patched to blend into the figured mahogany drawer fronts. The outline of the original appliqué carving was traced onto mylar and drawings made in keeping with the original shell carving; these became the basis for new appliqués which were then carved and glued onto the tympanum. New finials and plinths were also made; in the process of studying surviving evidence of the central plinth, the tail end of a dovetailed cartouche support was discovered. This feature may be restored in the future, but for now the eight-foot ceilings in the Henry Muhlenberg House, where the chest-on-chest is currently displayed, do not allow for such.

The original owner of the chest-on-chest is uncertain, as the family branch in which it descended derives from both Frederick Muhlenberg and his brother Henry Jr. due to intermarriages between cousins in the 1800s. The most likely scenario is that it was first owned by Frederick, who died prematurely in 1801 while living in Lancaster, Pennsylvania; many of his household goods were sold at auction and some were acquired by Henry Jr., who also lived in Lancaster. The original maker is also unclear, but Leonard Kessler (1737–1804) of Philadelphia is a likely candidate. One of the city’s leading German cabinetmakers, Kessler was a member of St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran Church. He is mentioned frequently in the journals of Henry Muhlenberg and is the only cabinetmaker the Muhlenbergs are known to have patronized while they lived in Philadelphia from 1761 to 1776.7

The chest-on-chest has anomalies, including a lack of quarter columns and the layout of the appliqué carving. Rather than flowing outward from the central shell, the carving instead emanates from the corners and flows toward the shell. Given that the carving is made as two separate units and then applied, it is possible that the cabinetmaker accidentally switched them. Although there is evidence to suggest that Kessler was both a joiner and a carver, making it plausible that he both built and carved the Muhlenberg chest-on-chest, it is possible that he was not accustomed to building major case pieces and may have been limited to working from memory of other examples. Despite its quirks, the chest-on-chest makes a powerful statement about the Muhlenberg family’s success in colonial Pennsylvania.

Lisa Minardi is the executive director of the Speaker’s House and director of collections and exhibitions for the Historical Society of Trappe. She is the author of Pastors & Patriots: The Muhlenberg Family of Pennsylvania.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2018 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized edition of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Henrietta Meier Oakley and John Christopher Schwab, Muhlenberg Album (N.p., 1910). Monroe H. Fabian, Joseph Wright: American Artist, 1756–1793 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1985), 130. With thanks to Ellen Miles and Brandon Brame Fortune of the National Portrait Gallery for locating Fabian’s notes.

3. Betty Blake’s Newport house and collection was the focus of an article by Gayle Hargreaves, “A Passion for Art and Life,” Antiques & Fine Art (Summer/Autumn 2007).

4. The Collection of Roy and Ruth Nutt: Highly Important American Silver, Sotheby’s, New York, January 24, 2015, lot 520.

5. Inventory of Matthias Richards, taken September 24, 1830, Reading, Pennsylvania. Berks County Register of Wills.

6. Benjamin A. Hewitt, Patricia E. Kane, and Gerald W. R. Ward, The Work of Many Hands: Card Tables in Federal America, 1790–1820 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1982), 188.

7. In 1763, Muhlenberg paid Kessler £10.2.6 for a set of chairs; eight are known to survive—all of which are presently on view at the Henry Muhlenberg House. Made of mahogany, the chairs have typical Philadelphia construction details and carving, but with larger volutes and other subtle differences that help distinguish Kessler’s work. See Lisa Minardi, “Philadelphia, Furniture, and the Pennsylvania Germans: A Reevaluation,” American Furniture, ed. Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), 230-41.