Art and Industry in Early America: Rhode Island Furniture, 1650–1830

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Anitques and Fine Art magazine.

The exhibition Art and Industry in Early America: Rhode Island Furniture, 1650–1830 is the culmination of more than a decade of research on the woodworkers and furniture of Rhode Island, resulting in an ongoing database of 3,000 objects available online in Yale University Art Gallery’s Rhode Island Furniture Archive. Art and Industry presents a comprehensive survey of Rhode Island furniture from the colonial and early Federal periods, including case furniture, formal seating furniture, clocks, and Windsor chairs. Drawing together more than 125 exceptional objects from museums, historical societies, and private collections, the show highlights major aesthetic innovations developed in the region. In addition to iconic, stylish pieces from important centers of production like Providence and Newport, the exhibition showcases simpler examples made in smaller towns and for export. The exhibition also addresses the surprisingly broad reach of Rhode Island’s furniture production, from the steady growth of the export trade throughout the eighteenth century to the gradual decline of the handcraft tradition in the nineteenth century. Reflecting on one of New England’s most important artistic traditions, Art and Industry in Early America encourages a deeper understanding of not only the artistry of thefurniture made throughout Rhode Island from the earliest days of the settlement to the late Federal period but also the industry its makers brought to the commercial system in which these objects were produced.

The following entries reflect the subject matter in the exhibition catalogue, written by contributors to the publication.

Early Rhode Island Furniture

by Dennis Carr

First settled by religious dissidents from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Rhode Island became a haven for colonists in the 1630s seeking greater religious freedom, land, and economic opportunity. The sturdy oak furniture made during the first hundred years of European settlement in Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay region mirrors the diversity of the immigrants, primarily English colonists, but also Dutch traders and French Huguenots. Following the destructive war with the Native American populations in southern New England, known as King Philip’s War (1675–1676), after the Wampanoag leader, Metacom, called King Philip by the English settlers, Rhode Island became part of a building boom that spread across eastern Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut.

Most of the surviving early Rhode Island furniture dates to this period, including an important oak wainscot chair that was reportedly owned by Hugh Cole (1628–1699/1700), a soldier in King Philip’s War and an early settler of Swansea, Massachusetts (Fig. 1). Cole’s house burned during the war, and in 1677 he rebuilt on land on the eastern shore of the Narragansett Bay that became incorporated into the town of Warren, Rhode Island, in 1747. Cole had negotiated with Metacom for the purchase of land in Swansea, and family lore has it that none other than the Wampanoag leader sat in this chair. The carved decoration on the back panel of the chair, with an incised diamond motif with stylized tendrils and roundels, relates it to three oak chests also made in the region, including a chest (Rhode Island Historical Society) that has a history in the Cranston family from Warren. Cole was a shipwright and his son, Hugh Cole (1658–1738), was a carpenter in the town.

|

|

Investigation into the historical records of Rhode Island has revealed the names of hundreds of craftsmen engaged in the furniture-making trades, as well as in the allied trades of house carpentry and shipbuilding, in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. It also shows the increasing presence of furniture makers not only in the major towns of Newport and Providence, but also in the smaller towns that ringed the Narragansett Bay, like Warren, Bristol, East Greenwich, Portsmouth, and Kingstown.

A recent discovery of a veneered walnut fall-front desk provides another extraordinary example of furniture from the eastern side of the Narragansett Bay, owned in the Child family of Swansea and later Warren (Fig. 2). The earliest recorded owner of the desk is James Child (1708–1737/8) of Swansea, whose son John married Rosabella Cole (1739–1820), great-granddaughter of Hugh Cole. The desk is an elaborate showcase of cabinetmaking, with thin walnut veneers decorating the outside and forty-six separate wooden compartments in the upper case alone, including an astonishing twenty-five secret drawers. The desk descended in the Child family until being consigned at auction in 2013. This object, like the Cole family chair, points to the development of fine furniture making in other towns around the bay outside of Newport and Providence, which are explored in the exhibition.

Cabinetmaking in Rhode Island, 1740–1830

by Patricia E. Kane

The period from 1740 to 1780 is considered the golden age of Rhode Island furniture making. Newport furniture made during this time has received the most attention, Providence somewhat less. Newport was led by the brothers Job and Christopher Townsend, their descendants, and apprentices. Early in this period, a few Providence and Bristol makers produced furniture ornamented with compass-star inlay and light and dark stringing (thin strips of inlaid wood in contrasting colors), decorative motifs more popular in Massachusetts. Beginning in the 1740s, evidence abounds of Rhode Island furniture makers participating in the export trade, shipping furniture to Canada, New York, the southern colonies, and the Caribbean.

At the outset of this period, case pieces and tables tended toward an austere silhouette, with sleek, serpentine-curved cabriole legs on slipper or pad feet. By the 1750s, however, the claw-and-ball foot, a sphere grasped by a claw, had become an alternative foot style. Sometimes the talons were undercut, a feature in the British colonies of North America unique to Rhode Island. At about the same time the shell, for which Rhode Island cabinetwork is renowned, began to be used. Rhode Island craftsmen carved this classic element of Baroque design out of dense mahogany with a voluptuousness and fluidity rarely matched. In marrying the shell to the block-front form (a façade of alternating convex and concave sections developed in Boston in the late 1730s), Rhode Island makers created some of the great masterpieces of American furniture. The earliest Rhode Island example dated by its maker is a 1764 bureau table by Edmund Townsend (Fig. 3) of Newport. Furniture with block-and-shell decoration was still being made in Rhode Island well after the American Revolution. Most were made in Newport, but the style was brought from Newport to Providence by makers relocating there, and a number of Providence craftsmen produced idiosyncratic interpretations. Cabinetmakers in smaller towns, such as Ichabod Cole in Warren, Rhode Island, also made block-and-shell furniture.

|

|

After the Revolution, Newport, having been occupied by the British during the war, struggled to rebuild itself, while Providence, which hadn’t been occupied, came into its own with expanded trade and manufacturing. Early Federal-period Rhode Island furniture is known for its distinctive pictorial inlay patterns ornamenting the legs of tables and case pieces. A sideboard believed to be from the Providence area sports a complex array of bellflowers, quarter-patera, and geometric inlay (Fig. 4). After 1805, Rhode Island furniture makers moved away from these pictorial inlays, introducing turned, reeded, or fluted legs and contrasting veneers to ornament their objects. The furniture now showed the influence of New York and Boston furniture, which began to be retailed in Rhode Island, and local makers began to import Boston inlay to use on their own work.

Early Seating Furniture

by Jennifer N. Johnson

The attribution of Rhode Island chairs has long presented significant challenges for scholars. Many chairs attributed to the colony on the basis of decorative features such as carved shells have been correctly reassigned to Boston. A focus on that city’s dominance in the chair making and upholstery trades during the first half of the eighteenth century, however, has served to obscure the substantial contributions made by Rhode Island. Through a careful reexamination of both the objects and their histories, Yale’s study has succeeded in clarifying the types of seating furniture produced by early Rhode Island craftsmen. For example, a pair of chairs that descended in the Coddington family of Newport have stylistic elements—crests with beak-like ends and pierced vasiform splats with a diamond-shaped central opening and scrolled shoulders—that confirm their Rhode Island origin. Their turned legs can be used as a touchstone for the identification of other Rhode Island turned chairs, like an earlier example recently given to Yale University Art Gallery with virtually identical turnings (Fig. 5). The Yale chair is a type previously attributed to Massachusetts or New Hampshire, but which can now be reassigned based on its relationship to the Coddington chairs. Turning patterns also play a role in differentiating Rhode Island cabriole-leg chairs from their Boston counterparts. In combination with other stylistic attributes and histories of ownership, they have enabled us to better define the various types of Queen Anne and Chippendale chairs produced in Rhode Island.

|

|

Yale’s study has brought to light several previously unknown Rhode Island upholsterers, at least five of whom were active in Newport prior to 1750. An armchair discovered near the Connecticut–Rhode Island border—with turned front legs, Spanish feet, scrolled handholds, and a yoke-carved crest—is representative of the types of objects on which they collaborated with early Rhode Island chair makers. A remarkable survivor, it retains its original leather upholstery, grass stuffing, and ornamental brass nails. Another recent discovery is an easy chair (Fig. 6) that retains much of its original embroidered show cover. Its embroidery includes an open workbasket and flowering vines, the latter based on the “tree of life” motif found on imported Indian palampores. The needlework design strikingly resembles that of an easy chair given by William Ellery of Newport to his daughter Almy on the occasion of her marriage. It is conceivable that the pattern for the embroidery of these chairs was laid out by the same hand or with related templates, possibly imported from London or copied from London prototypes.

Clockmaking in Colonial & Early Federal Rhode Island

by Gary R. Sullivan

For over one hundred years, beginning in about 1720, cabinetmakers in Rhode Island manufactured the cases for eight-day clocks known today as tall case or grandfather clocks. The movements for these clocks, almost all of which were brass, were made by different groups of skilled craftsmen. The original owners of many early Rhode Island clocks were prominent merchants, political leaders, entrepreneurs, landowners, ship captains, and at least one physician.

William Claggett was one of the most prolific clockmakers in all of colonial America; more than fifty of his clocks are known to survive.1 One of Rhode Island’s earliest clockmakers, he arrived in Newport from Boston by 1716.2 Most of Claggett’s earliest Rhode Island clocks have square dials and are housed in cases with sarcophagus hoods (stepped, molded tops). The earliest of those are ornamented with burl veneer. By the 1740s, Rhode Island cabinetmakers were producing a new style of clock case, with concave blocking capped by a carved shell on the pendulum door (Fig. 7). About a half-dozen such clocks are known. They house movements by William Claggett, his son-in-law James Wady, and the Providence clockmaker Samuel Rockwell.3 They have elaborately scrolled pediments atop an arched frieze, often ornamented with pierced decoration in metal, wood, or paper. The concave blocking and carved shells on the pendulum doors of this group are often richly enhanced by gilding. With these cases, Rhode Islanders were introduced to the idea that a carved shell was a suitable ornament for the top of a pendulum door.

|

|

Beginning around the 1750s, cases with convex block-and-shell pendulum doors succeeded the concave model (Fig. 8). About one hundred of these iconic cases are catalogued in the furniture archive. Most have doors with the blocked section cut from a single piece of wood (some have applied shells). On the others, the door is framed (assembled from rails and stiles), with blocking and shells applied to the front.

The colonial clock hoods invariably consist of an arched pediment ornamented with finials, often with a keystone in the entablature, and fluted colonettes at the corners. Rhode Island clock cases exhibit other regional characteristics. The molding between the waist and the base is usually ogee-shaped as opposed to cove-shaped, universal on other New England clocks. The sidelights on the hoods (if present) are not openings cut into a solid piece of wood but are often framed of four pieces around the glass.

Clock making in Rhode Island reached its peak in the eighteenth century. The tall case clocks from the second half of the eighteenth century with their innovative designs by talented cabinetmakers rivaled the world’s finest. As the nineteenth century approached and Federal-style cases with painted dials and surfaces embellished with veneered and inlayed surfaces came into fashion, Boston, only fifty miles away, emerged as the new center for American clock production. In 1802, Boston clockmakers dealt a blow to Rhode Island clockmaking when Simon Willard developed his patent timepiece, today called the banjo clock. These newly fashionable wall clocks included finely painted eglomisé panels and were more affordable than tall case clocks. Banjo clocks grew in popularity and, by 1810, had almost entirely replaced tall case clocks, not only in Rhode Island but throughout New England.

Although a number of tall case and banjo clocks were made in Rhode Island after 1810, clock making by individual craftsmen was quickly fading; Connecticut factories were producing ever-cheaper clocks, many with wood movements. Nevertheless, Rhode Island clockmakers and the cabinetmakers with whom they worked have left an incomparable body of work—some of the most remarkable and beautiful clocks made in early America.

-----

2. Thanks to Donald L. Fennimore and Frank L. Hohmann III for sharing their research on William Claggett.

3. For the clocks by Wady, see Hohmann et al. 2007, 302–3, no. 94, ill. [RIF227]; Hohmann et al. 2007, 300–301, no. 93, ill. [RIF2299]; and Winterthur Museum, Del., inv. no. 1951.0028 [RIF2303]. For the clocks by Claggett, see Diplomatic Reception Rooms, U.S. Department of State, Washington, D.C., inv. no. 89.6 [RIF668] and Failey 1998, 66–67, no. 74, ill. [RIF1176]. For the Rockwell clock, see RIF2320.

Windsor Chair Making in Rhode Island: An Overview

by Nancy Goyne Evans

- Fig. 9: Sack-back Windsor armchair, probably Providence, ca. 1780–1785. Maple, ash, and oak. H. 37-1/4, W. 28-1/2, D. 15-3/4 in. Probably Norman Herreshoff House, Bristol, R.I. A notable feature of this chair is its overbuilt construction that includes a thick bow mounted low and forward and extensive pinning. This prototype Windsor is one of an original pair. It was owned by a direct descendant of Rhode Island merchant John Brown. Its mate bears the incised inscription “I.BROWN” on the top surface of the proper-left arm terminal and is in the collection of the Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence. (RIF1269).

Although Newport was the first center of Windsor chair making in New England, almost none of its makers branded, labeled, stenciled, or otherwise identified their products, and few left more than scattered written transactions with customers. Unlike other seating, the basic construction unit of the Windsor is the wooden seat plank, contoured for comfort, and drilled with holes, top and bottom, to independently socket the back structure and undercarriage.

The earliest craft evidence for Newport occurs when Jonathan Cahoone billed a customer sometime before May 1763 for two high-back Windsors.4 Cahoone may have also constructed twelve low-back Windsors purchased the following year for the Redwood Library founded by Abraham Redwood.5 The Reverand Ezra Stiles, an early library member, was painted seated in a similar green low-back Windsor. As membership grew, the library acquired a number of high-back Windsors. Both groups are distinctive for their use of cross stretchers, describing the influence of formal seating. Other structural influences flowed from Philadelphia and English Windsor chair making. The chairs were painted verdigris green, derived from early English use of green-painted Windsors on the grounds of country estates. American Windsors, used principally indoors, remained green through the Revolution. Aaron Lopez, a Jewish merchant of Newport, purchased green Windsors with low and high backs in the late 1760s and 1770s for his extensive maritime trade.6

Provenance identifies a variable group of about two dozen Windsors made in Providence in the sack-back pattern in the late colonial period (Fig. 9). The chairs relate in general to the Redwood Library chairs, although they introduce S-curved arm posts, nodular spindles, H-plan stretchers, and distinctive baluster-turned legs.

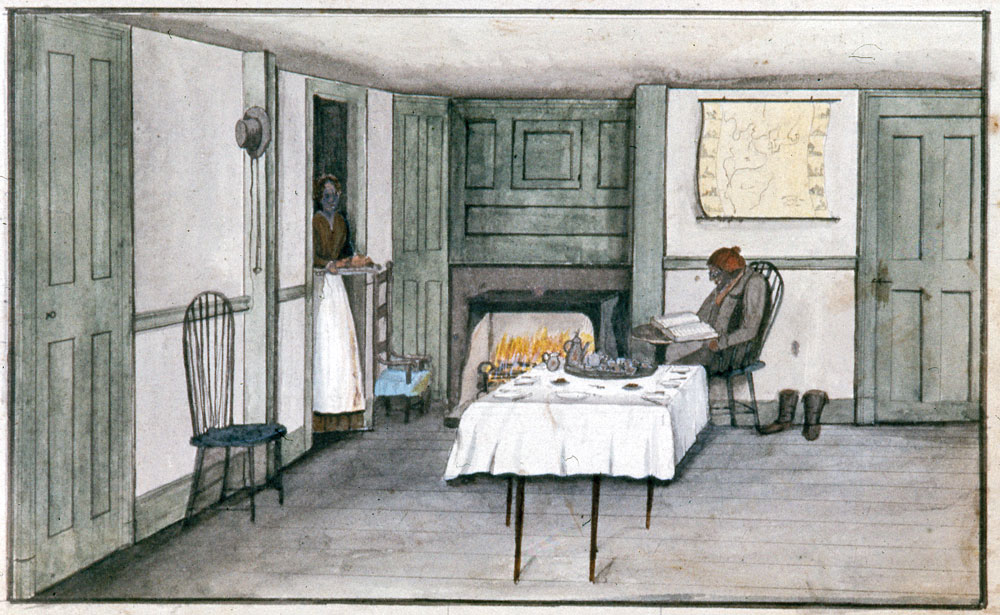

A rare body of records highlights use of Windsor seating in Rhode Island government facilities, from colony houses to statehouses, from the 1760s through the mid-1790s.7 Postwar Windsor production at Providence for domestic use is indicated in the accounts of the Proud brothers and in a circa-1795 portrait of Capt. Samuel Packard seated in a sack-back Windsor (Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence).8 Household accounts for Dr. Isaac Senter of Newport document an active patronage of chair maker Joseph Vickary, while a watercolor drawing illustrating bow-back Windsors depicts the dining room of Dr. Whitridge at Tiverton (Fig. 10).9

Rhode Island, particularly Newport, suffered measurably from British occupation during the Revolutionary War. Recovery was compromised during the 1780s by the circulation of paper money, which depreciated, creating difficult business conditions, and by the reluctance of Rhode Island to join the federal union until 1790. The political turmoil impacted Windsor design and production sufficiently that no recognizable Rhode Island style emerged until the 1790s, when Providence led in commerce. Meanwhile, New York had risen to prominence and developed the stylish continuous-bow Windsor, based on the French bergère chair. These and other Windsors shipped from New York beginning in the 1790s augmented Rhode Island’s waterborne trade.10 Pale yellow became a popular new Windsor color with the introduction of simulated bamboo turnings.

- Fig. 10: Joseph Shoemaker Russell (1795–1860), Dining room of Dr. Whitridge, Tiverton, Rhode Island, ca. 1848–53, depicting a scene of 1814–1815. Watercolor on paper, 7-1⁄16 x 9-1/2 inches. New Bedford Whaling Museum, Mass. The roaring fire in the Franklin stove and the doctor’s attire indicate the season is winter. The family is about to enjoy a delicious breakfast of “Pot-Apple-pie.”

New directions in merchandising emerged in the nineteenth century, as manufacturing blossomed and a rising middle class demanded cheaper goods in the marketplace. The answer was the furniture wareroom, where household goods could be displayed and quickly restocked locally or from out-of-state production centers. Christian M. Nestell, a participant in this trade, is the rare Windsor craftsman identified with known nineteenth-century Rhode Island Windsors.11

-----

5. “Record Book of the Proceedings of the Annual and Special Meetings of the Redwood Library Company,” Newport, 1747 and later, Redwood Library and Athenaeum, Newport.

6. Aaron Lopez outward bound invoice book, Newport, 1763–1768, Newport Historical Society.

7. All recorded in Rhode Island treasurer’s receipts, Rhode Island State Archives, Providence.

8. William Proud, later Daniel and Samuel Proud ledger, Providence, 1770–ca.1825, and Daniel and Samuel Proud daybook and ledger, Providence, 1810–1834, Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence.

9. Accounts for the household of Dr. Isaac Senter and family, Newport, 1786–1800, are cited in Joseph K. Ott, “Recent Discoveries Among Rhode Island Cabinetmakers and Their Work,” Rhode Island History, vol. 28, no. 1 (Feb. 1969): 8–9.

10. Newport inward and outward entries, 1790–1800, U.S. Custom House Records, Federal Archives and Records Center, Waltham, Mass.

11. See Nancy Goyne Evans, “The Christian M. Nestell Drawing Book: A Focus on the Ornamental Painter and His Craft in Early Nineteenth-Century America,” in American Furniture 1998, ed. Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1998): 99–163.

Art and Industry in Early America: Rhode Island Furniture, 1650–1830 opens at Yale University Art Gallery on August 19, 2016 and runs through January 8, 2017. The exhibition is organized by Patricia Kane; a catalogue with contributions from this article’s authors is available through Yale University Press. For more information visit artgallery.yale.edu. The Rhode Island Furniture Archive is available at www.rifa.art.yale.edu.

-----

Patricia E. Kane is the Friends of American Arts Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, and director of the Rhode Island Furniture Archive; Dennis Carr is the Carolyn and Peter Lynch Curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture in Art of the Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Jennifer N. Johnson is Rhode Island Furniture Research Associate, American Decorative Arts, Yale University Art Gallery; Gary R. Sullivan is a nationally recognized American art and antiques dealer, author, and independent researcher; Nancy Goyne Evans is an independent furniture historian.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2016 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.