Risky Business: The Perils and Rewards of Hunting in American Art

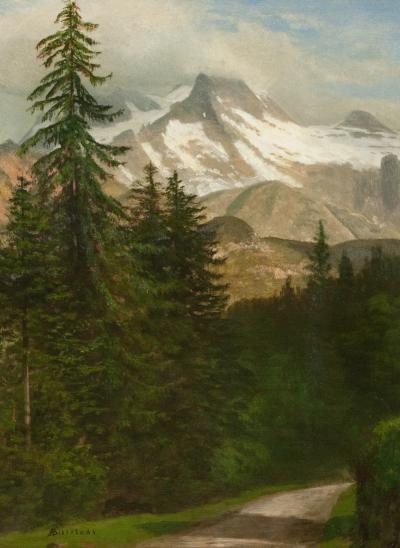

Suspense-filled depictions of close calls, tight spots, and struggles to the death enjoyed great popularity in American art during the second half of the nineteenth century. As the country moved full steam ahead toward modernity, many Americans romanticized a past that held preindustrial activities in high esteem, including rugged and risky excursions in the wild. The visual culture that emerged around hunting reflected the social and economic anxieties and successes of rapidly changing times by illustrating the harsh environments and dramatic confrontations endured in pursuit of quarry, whether for commerce, diversion, or sustenance.

The English-born artist Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819–1905) found inspiration in the hard-scrabble life and craggy terrain of New York’s Adirondack Mountains. His paintings perpetuated the archetype of the brave hunter who, through courageous acts, conquered and tamed America’s wilderness. The symbolic implications of such works reflected social anxieties of the time while reinforcing the power of individuals and, in turn, the nation. His painting The Hunter’s Dilemma (Fig. 1), reflects a common storyline in American paintings of the second half of the nineteenth century—the mortal predicament. This theme reflected cultural stresses caused by rapid industrialization—as well as the promises and perils of westward expansion—where the potential rewards were worth the risk of hardship, harm, and possible failure. Potentially sacrificing life and limb to retrieve his kill, the hunter in Tait’s painting has climbed down onto a ledge set halfway up the face of a sheer cliff. Dressed in buckskin, a traditional garb that appears throughout popular culture as the costume associated with such heroic figures as Daniel Boone, the young man confronts—and pursues the challenge of—the seemingly insurmountable obstacle of hoisting his dead quarry to higher ground.

Whereas Tait depicted hunters as heroic figures who conquer nature in the face of seemingly extreme difficulties, Charles Deas’ The Death Struggle (Fig. 2) portrays the hunter as an interloper and scoundrel who plunders nature’s bounty for personal gain with complete disregard for trespassing. Painted by Deas at the beginning of a debilitating psychological breakdown, this nightmarish scene depicts a fur trapper and a Native American warrior embracing each other as their horses careen over the edge of a cliff.1 Considered one of Deas’ most emotionally expressive and artistically important works, it reflects the mental anguish the artist was experiencing at the time, and captures the violent tension that existed between diverging commercial and cultural interests on America’s Western Frontier. The uncertainty of the fates of both the warrior and trapper also mirrors a broader anxiety caused by the violent conflicts between the two cultures and its impact on the future of the West.

The earliest European narratives of the New World painted a forested land teeming with catamounts, wolves, and especially bears. With industrialization in the nineteenth century, images of men who came face-to-face with bears, the most powerful predator on the North American continent, took on a larger meaning for factory workers in burgeoning urban centers who would have recognized and identified with the dangers bears posed because they too faced risks. Instead of the jagged teeth in a bear’s maw, laborers confronted the regularly spaced teeth of sprockets and cogs that could devour human limbs with the same ferocity. In A Tight Fix—Bear Hunting, Earl Winter (The Life of a Hunter: A Tight Fix) (Fig. 3), painted in 1856, the only thing standing between the hunter and being mauled to death is his companion in the background, taking aim at the bear with his rifle, suggesting hope in an uncertain world.

For the brave, the potential for reward outweighed the many life-threatening risks associated with hunting and fishing. Commercial hunters, as depicted in Winslow Homer’s Huntsman and Dogs (Fig. 4), and N. C. Wyeth’s fisherman in Deep Cove Lobsterman (Fig. 5), saw the outdoor life as offering a livelihood. For the sportsman, a trophy provided an impressive symbol of masculinity and mortality, and nostalgia by memorializing the thrill of the hunt. A growing number of sportsmen recorded the success of their hunt with a trophy painting. Artists responded by creating trompe l’oeil still lifes, painted so realistically as to present the depicted objects in three dimensions. These portrayals of lifeless animals visually transformed elegantly appointed Victorian parlors into trophy rooms, and ornately decorated dining rooms into showcases where the well-to-do dined amid a smorgasbord of nature’s bounty of deer, fish, rabbits, and wildfowl, forever immortalized in paint and on elaborate sideboards carved with images of game. While dining in the presence of carved carcasses and painted corpses might seem distasteful to modern sensibilities, Victorians viewed these images as affirmations of man’s biblically sanctioned dominion over animals.2

During the last quarter of the 1800s, Irish-born William Michael Harnett became one of the leading trompe l’oeil artists working in the United States, inspiring a legion of painters, including John F. Peto and John Haberle. During his lifetime, Harnett painted several different versions of After the Hunt (Fig.6), featuring realistically rendered dead game suspended alongside the instruments of their demise, and set against the backdrop of painted doors with elaborate iron hinges. Critics often praised his skills for testing the limits of their perceptions with his convincingly realistic paintings. Newspaper articles often reported incidents where incredulous viewers reached out to touch the objects he had depicted.3

Painters like Astley D. M. Cooper used trompe l’oeil to immortalize a passing way of life. The Buffalo Head (Relics of the Past) (Fig. 7) was originally owned by William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who proudly displayed it in the lobby of his Irma Hotel in Wyoming. The largest in Astley’s series of trompe l’oeil paintings on the subject, it paid tribute to the legendary life of Buffalo Bill and the vanishing Wild West. The taxidermied buffalo head in the center of the painting was intended to remind viewers of the dwindling population of bison that once roamed the Western Plains in herds of millions, as well as one of their most celebrated hunters. Buffalo Bill earned his nickname after purportedly shooting more than four thousand bison while supplying meat for the Kansas Pacific Railroad workers.

Wild Spaces, Open Seasons: Hunting and Fishing in American Art, a traveling exhibition organized by Shelburne Museum, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, the Joslyn Art Museum, and the Dixon Gallery and Gardens, is on view at Shelburne Museum from June 3 until August 27, 2017. It is the first major exhibition to explore American artists’ fascination with hunting and fishing from the nineteenth century through the end of World War II. This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on The Arts and the Humanities. For information call 802.985.3346 or visit www.shelburnemuseum.org.

Kory Rogers is head curator at the Shelburne Museum, Shelburne, Vermont.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

2. Kenneth L. Ames, Death in the Dining Room & Other Tales of Victorian Culture (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1992).

3. Michael Leja, Looking Askance: Skepticism and American Art from Eakins to Duchamp (Berkley, LA and London: University of California Press).