Robert McGuffin

Journeyman Extraordinaire for Henry Connelly, Part I

In the early nineteenth century, the newly minted American republic was a prosperous and dynamic place. Its urban centers were developing rapidly, with a newly affluent population hungry to furnish their homes in the latest styles emanating from Britain and Europe. Having been the seat of government for a decade, cosmopolitan Philadelphia supported a cabinetmaking trade that produced furniture in the most fashionable neoclassical taste. For over a hundred years, collectors, scholars, and curators have tried to piece together a deeper understanding of these beautiful objects and the talented people who made them.

Unfortunately, many of the early attributions attached to Philadelphia work in this period—names like Ephraim Haines, Henry Connelly, and Joseph Barry—were not based on careful visual and structural analysis of the few documented or labeled pieces extant. Not only do these loose labels tend to misidentify the unique work of specific cabinetmakers and shops, but they also oversimplify the complex structure of the cabinetmaking industry in urban centers at the time. The product of a shop was rarely the work of a single craftsman. In Federal Philadelphia it was more likely the combined effort of master, foreman, journeymen, apprentices, and outside specialists to whom specific skilled tasks were frequently outsourced.

- Fig. 2: Robert McGuffin (1779/1780–after 1863). Photograph from a glass plate negative in the collection of the Lawrence County Historical Society, New Castle, Pennsylvania. The photograph was published in the “Fifth Annual Old Timers Picnic Pamphlet” dated August 10, 1911. Sankey Glass Slide Collection, Lawrence County Historical Society.

Illustrating the point, recent scholarship has uncovered the name of George G. Wright, a journeyman and then foreman in Joseph Barry’s shop who spearheaded the manufacture of many iconic pieces while his master was off developing business contacts and traveling to Europe to bring back the latest styles and goods.1 Now scholarship has added another signed table to the known work of Robert McGuffin, who was a journeyman in Henry Connelly’s (1770–1826) shop before setting up an independent business of his own.2 This discovery allows the attribution of more pieces produced in that important shop. McGuffin’s life and work link him to some of the most striking examples of neoclassical design in America and illustrate some of the challenges faced by the cabinetmaking trade as it underwent organizational changes in the early nineteenth century.

McGuffin was known to be working in Connelly’s shop when he made an elaborately inlaid satinwood card table inscribed in florid graphite script underneath the stationary leaf: “McGuffin 1807” (Fig. 1).3 The extravagant use of satinwood and virtuoso veneer work places the Connelly shop at the top of the market and shows that McGuffin played a pivotal role there. It also confirms Robert McGuffin as one of the most skilled cabinetmakers in Federal Philadelphia during a brief period of intense creativity before changes in the trade and the War of 1812 forced him to move on.

Robert McGuffin (1779/1780–after 1863) was born in Newton Township in Cumberland County, Pennsylvania (Fig. 2). The identity of his parents is uncertain because several Robert McGuffin’s were born there in the same period. What is certain is that the extended McGuffin family of Cumberland County emigrated from the Irish town of Knockgorm in County Down before 1753. As a boy, Robert probably watched as the town of Newville sprang up on land owned by the Big Spring Presbyterian Church. Founded in 1790 on the road between Carlisle to the east and Shippensburg to the southwest, by 1798 Newville encompassed forty-one houses and boasted a population of about 300.

- Fig. 3: Sideboard made by Robert McGuffin, for Henry Hollingsworth, and labeled by Henry Connelly, Philadelphia, 1806. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, yellow poplar, white pine, dark wood stringing and silvered brass handles, escutcheons and hinges. H. 41, W. 72, D. 25⅞ in. Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photography by Gavin Ashworth.

Remarkably, there were six cabinetmakers working in this rapidly developing town in the 1790s: Henry Connelly, John Peebles, John Bratton, John Fox, James Caldwell, and Archibald Cambridge. Just what drew so many cabinetmakers to the town is unclear, but partnerships among the Newville cabinetmakers were readily formed, dissolved, and re-formed. In the early 1790s, Henry Connelly and John Peebles went into business together, and dissolved their partnership in 1796. When Peebles returned to his home town of Shippensburg, Connelly immediately joined forces with Newville cabinetmaker John Bratton. That partnership was short lived, as Connelly had left Newville by 1799.

Though there is no proof that McGuffin performed his indenture in Newville, it is a logical assumption given so many active cabinetmakers in the vicinity. McGuffin had a connection with at least two of the cabinetmakers in Newville. In 1799 he witnessed a deed there for cabinetmaker John Fox, and sometime before 1806 he joined Henry Connelly’s shop after Connelly moved to Philadelphia.4

Given these connections, it is likely that McGuffin apprenticed in one of these two men’s shops in Newville. If he began his apprenticeship with Connelly at the customary age of fourteen, he would have completed four or five years of service just about the time that Connelly disappears from the written record in Newville in 1799. Given McGuffin’s skills showcased in his later signed pieces, Connelly would have been anxious to hire him as a journeyman after establishing a shop in Philadelphia. If McGuffin learned his trade from John Fox, he may have witnessed the deed for Fox at the end of his apprenticeship or as a newly minted journeyman working for him.

Three pieces of Robert McGuffin’s signed and dated Philadelphia work reveal the role that he and Henry Connelly played during this period of great prosperity. Having been the seat of the Federal government in the last decade of the eighteenth century, Philadelphia became the financial, commercial, and maritime capital of the nation in the boom years just prior to the War of 1812. The group includes the inlaid satinwood card table in figure 1, a mahogany sideboard labeled by Henry Connelly and inscribed “Robt McGuffin/ maker (?)/1806” (Fig. 3) and an inlaid satinwood sewing table inscribed “Made by/Robert McGuffin/1808/72 4th Street/Philad” (Fig. 4). Through careful analysis of the methods of construction and handling of materials in this documented group, other unmarked furniture can now be attributed to McGuffin’s hand during this important decade.

In the 1950s, veteran collector Walter Morrison Jeffords Jr. (1915–1990) encouraged the Philadelphia Museum of Art to acquire a neoclassical kidney-shaped sideboard owned by the descendants of the prominent banker Henry Hollingsworth (1781–1854). The sideboard bears the printed card label of Henry Connelly nailed to the back of the proper left door, covering the posts and nuts that secure the silvered hardware on the façade (Fig. 5). Well after the sideboard was accessioned by the museum, McGuffin’s inscription was discovered in red chalk on the underside of the dust board beneath the central drawer.5

Henry Hollingsworth ordered the sideboard from Connelly in 1806, probably in preparation for his marriage that same year. It is also possible that it was ordered by his father, Levi Hollingsworth (1739-1824), as a wedding present for Henry and his new bride. At first glance, the sideboard looks fairly simple with no contrasting inlay or complex veneering features, but the form is intentionally conservative and the materials are rich. The carefully selected branch mahogany veneer on the doors and drawers are from the same flitch, applied in opposing directions on each side. All the horizontal elements are crossbanded with straight-grain striped mahogany. The false and working drawers and doors are edged with ebony stringing, as is the band applied around the lower edge of the case. The silver-plated hardware, including oval handles, door hinges and diamond-shaped escutcheon plates, would have been quite costly in 1806.6 The smooth bulbs above the finely reeded legs eschew the ubiquitous leaf carving in order to accentuate the materials and sculptural serpentine front and kidney-shaped ends.

- Fig. 6: Detail of the rayed top on the card table illustrated in fig. 1. Note how McGuffin used dark stringing to separate each ray, and placed a dark arc at the wide end of each ray. He also used the same rosewood crossbanding around the edge of the top of the sewing table seen in fig. 4. Photography by Gavin Ashworth.

There is a gap in the written record for McGuffin after 1799. However, the inscription on the 1806 Connelly sideboard, along with the tax assessment ledgers for 1808 and 1809 put him back into the historical record, where we can track him into his mid-eighties in New Castle, Pennsylvania.7 What he did in the unrecorded years is uncertain, but he probably had proven himself as a skilled and valued journeyman in Connelly’s shop well before being given the task of executing a commission from one of the firm’s most important clients.

The second known signed example is a highly inlaid satinwood card table dated 1807 (fig. 1). One of a pair, these tables probably represent the high-water mark of his career as a cabinetmaker.8 Costly in every respect, they were undoubtedly commissioned by a prominent (but not yet identified) client. That McGuffin was given the job of executing these extravagant tables shows that he was someone Connelly could depend on for the very best work produced in the shop.

The kidney shape of the tables echoes the shape of the sideboard, though the centers are hollow as opposed to serpentine. The Journeymen Cabinet and Chairmakers’ Pennsylvania Book of Prices, 1811, lists the base price paid to journeymen for making a “Kidney End Card Table with Serpentine Middle” as $4.68 (the hollow center was an extra option), the most expensive form listed in the card table section. The materials are some of the richest seen in any product of an American cabinetmaking shop during the neoclassical period. Imported from Sri Lanka or South America, the intensely curled satinwood veneers used for the rayed top and aprons and the solid satinwood for the four legs were very rare and must have cost the client dearly. The rosewood crossbanding, ebony stringing, and fractional circles, branch mahogany for ellipses and semicircles, and the patterned inlay for the apron added even more expense to the materials. In addition, many extra hours of McGuffin’s virtuoso veneering skills were required to execute such an ambitious design so masterfully.

McGuffin employed a dynamic play of geometric shapes in his visual vocabulary for the tables. Emanating from the rear of the top, he fashioned a semicircle of scalene triangles that radiate out to terminals made of fractional circles. This sunburst was captured in a frame of rosewood crossbanding surrounded with ebony stringing.9 The apron is inlaid with four crossbanded rectangles with a larger one in the center framing a pointed ellipse on a field of mitred satinwood. The stiles of the legs are inlaid with smaller pointed ellipses captured within dark rectangles with ovolo corners.

A close look at McGuffin’s veneering and inlay work reveals a sophisticated system of visual composition. He carefully sets the parallel grain patterns of the curly veneers in opposing directions to emphasize the symmetry of the design and to create a subtle tension in the broad expanses of satinwood in the top. He also added ebony stringing between each ray and ebony fractional circles at the ends of each ray to create a sense of depth and perspective (Fig. 6). Unlike most American Federal card tables, the band of patterned inlay at the bottom of the apron is interrupted by the central rectangle, manipulating the eye to the ellipse at the center of the composition. In addition, the pattern is formed by repeating arrows that literally point the eye to the center of the concave apron. The rosewood banding used to frame the top and for the apron rectangles are all flanked by light and dark stringing, masterfully accentuating the eye-popping impact of the contrasting woods.

The third signed example is a satinwood sewing table (fig. 4). In 1936, Joe Kindig bought the table from an old Germantown family and offered it simultaneously to Henry Francis du Pont and Francis Garvan. The latter bought it and it later became part of the collections at the Yale University Art Gallery. Almost fifty years after the 1936 purchase, Robert McGuffin’s inscription and the date 1808 were discovered on the underside of the proper right interior well, partly covered by an applied drawer guide. The table was ordered by the wealthy merchant Henry Pratt (1761–1838), who probably gave it to his daughter Susan Theresa Pratt on the occasion of her wedding to Charles Frederick Mayer of Baltimore in 1819.10

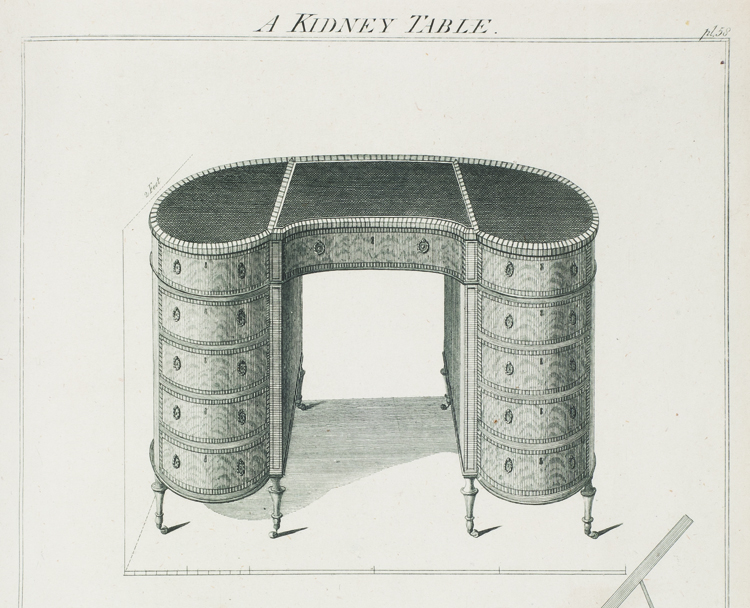

Like the signed examples discussed above, the 1808 sewing table is a variation on the kidney shape popularized by Thomas Sheraton and much favored in Philadelphia. Connelly and McGuffin lifted the shape quite literally from Plate 58 in the 1793 edition of Sheraton’s Drawing Book (Fig. 7). Sheraton’s table could be used as a lady’s dressing or reading table but the Philadelphia cabinetmakers adapted the idea for a sewing table, perhaps combining it with a “Ladies Work Table,” Plate 26, in the Appendix to the Drawing Book of the same year (Fig. 8).

These three pieces of signed furniture give us a window into Robert McGuffin’s talents and expand the oeuvre of known work from Henry Connelly’s shop. They also provide a foundation from which more pieces from McGuffin’s distinctive hand can be attributed. This discussion will appear in a later article.

Clark Pearce is an independent scholar and consultant to museums and collectors in American arts and is based in Essex, Massachusetts. Merri Lou Schaumann is an independent historian and author based in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Catherine Ebert is a collector and independent scholar based in Florida.

2. See tax records showing Robert McGuffin working in Henry Connelly’s shop, “Philadelphia Furniture Makers, 1800–1815,” Deborah Ducoff-Barone, Antiques (May 1991): 988, 981.

3. Wendy Cooper of Winterthur Museum and Tara Chicirda of Colonial Williamsburg discovered and identified the inscription in 2006.

4. See “Henry Connelly, Cabinet and Chairmaker,” Merri Lou Scribner Schaumann, Cumberland County History, 13, no. 2 (Winter 1996): 91–98.

5. See “Henry Connelly, Cabinet and Chairmaker,” International Studio, 93, no. 384 (May 1929): 42–46, figs. 2, 3. Philadelphia Museum of Art museum files, courtesy Alexandra Kirtley.

6. Silver plated hardware was available in Philadelphia in the early nineteenth century. George Armitage offered in the Aurora General Advertiser (January 3, 1809) “…silver plated knobs for cabinet ware of the newest fashion…”

7. Ducoff-Barone, Antiques (May 1991): 988, 991.

8. The mate to the inscribed table sold at Sotheby’s New York, Important Americana, lot 836, January 17, 1999.

9. See George Hepplewhite, The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide, third edition, 1794, Plate 63 for tabletop designs with rayed veneers.

10. See David Barquist, American Looking Glasses and Tables (Yale University, 1992), 290–293, for a thorough discussion of the sewing table.