Rockwell Kent's Egypt

Shadow and Light in Vermont

“Egypt,” an idyllic hill farm situated in an isolated hollow high on the slopes of Red Mountain in Arlington, Vermont, served as home base for the artist Rockwell Kent (1882–1971) and his growing family from the summer of 1919 to the summer of 1925. Arriving in Vermont on the heels of a sojourn to Alaska and buoyed by the critical and financial success of the work he had commenced there, including his travel memoir, Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska, Kent quickly rose to become one of the most renowned artistic figures in America. Despite the fact that this period proved to be pivotal in the arc of Kent’s career, the artist’s seminal years in Arlington have been largely overlooked.

Local lore claims that long before Kent arrived in Arlington the farm he purchased was miraculously spared from an early frost that destroyed crops in the surrounding region. Subsequently, the harvest from this area was shared with others in the community, sparing them from famine. This story echoes the biblical tale of Joseph, as told in the book of Genesis, who saved his brothers and extended family from starvation and drought, and was the inspiration for the name Kent gave the farm.

Shortly after he had purchased the farm, Kent clarified his artistic vision: “I don’t want petty self-expression; I want the elemental, infinite thing; I want to paint the rhythm of eternity.” 1 A spiritual descendant of William Blake, Walt Whitman, and Friedrich Nietzsche, the artist found much inspiration in both the awe-inspiring physical landscape that surrounded him and in his own internal musings on life, death, and man’s place in the world. A focused examination of the artist’s time in Vermont reveals a complex, psychologically probing body of work. Looking at the paintings, drawings, and prints that Kent created during this period reveals, often simultaneously, both the shadowy recesses and light-filled aspects of humanity. In “Egypt” Kent was able to harvest a body of work that conveys the full spectrum of human emotion, from anguish to ecstasy.

Between August 1918 and March 1919, as an immediate prelude to his time in Arlington, Kent and his nine-year-old son Rockwell III (known as “Rocky”) went on a Robinson Crusoe-like adventure, living in a converted goat shack on Fox Island, a seventeen-mile boat ride off the coast of Seward, Alaska. With the freedom of solitude, Kent commenced work on over a dozen large-scale paintings and executed dozens of smaller plein air oil sketches that he referred to as “impressions.” The artist’s first ten months in Vermont were devoted almost exclusively to finishing the work he had begun in the far Northwest.

While most of Kent’s smaller-scale Alaskan “impressions” were painted quickly and finished in one session, this one is dated 1920, indicating that it was likely completed in Arlington. The “impressions,” were not “studies” in the traditional sense. Kent considered his “impressions” to be fully realized works of art and exhibited them as such.2 The compositions are typically divided into three basic bands of color—foreground, sea; middle ground, mountains; and sky. This compositional simplicity is in keeping with Kent’s spare modern aesthetic, where the objective was to lay down an effective overall design rather than dwell in specifics. In their similarities to Vermont Study, undoubtedly the first oil on canvas the artist conceived in Vermont, the “impressions” provide insight into Kent’s artistic transition from Alaska to Vermont.

Vermont Study is undoubtedly the earliest oil painting that Kent conceived in Vermont and closely relates to the artist’s “impressions” from Alaska, in terms of its physical characteristics, style, technique, and compositional strategies. Mt. Equinox loomed over Kent’s Arlington studio like a sentinel. At 3,850 feet, it is the highest peak in the Taconic Range and the second highest in southern Vermont. It was within the inspiring environment of this deeply moving, one might say sacred, landscape that Kent’s creative energies were able to flourish during his Vermont years. In this first attempt at recording the prominent landmark, the artist exaggerated some of the mountain’s topographical details. Despite these alterations, Vermont Study offers evidence of a powerfully observant eye, capturing the distinctive character of the landscape surrounding “Egypt,” with its open pastures bounded by tree-lined perimeters and forest.

During the summer of 1920, with his Alaskan project behind him, Kent worked on a group of tightly executed, delicately rendered graphite portraits of close family members and friends. Returning to the basics, a practice he learned during his school years under Robert Henri, the artist prepared to embark on a new body of work based on his surroundings. In a letter dated August 24, Kent noted, “Lately I have been making very careful portrait drawings, the most ‘old fashioned’ detailed studies. Out of this study I hope to evolve a form of simple characterization. It goes against my nature to work without possessing a thorough and exact knowledge of it. Out of this one can then evolve, if he pleases, that simple statement which is his art.” 3 This drawing of Kent’s wife, Kathleen Whiting, is the result of that exercise. Kent’s soft, monochromatic shading lends the portrait an air of timelessness. The drawing is classically rendered, reminiscent of Roman marble bust portraits, while depicting a decidedly modern sitter, with her thin ribbon hair-tie and bobbed hairdo.

Looking due south from Kent’s studio, a couple relax on the ground with their heads bowed in reverie, seemingly unaware of the transcendent view behind them. The painting’s palette, with its tawny foreground and mauve tinged mid-ground melting into an azure sky, suggests the subtlety of transition, the time of year being late autumn or early spring. An unusually regular pattern of peaceful cotton-ball cumulus clouds float in the sky, forming a slight arc in the foreground. The arc is a motif that Kent used on multiple occasions to suggest a symbolic threshold, or transition from the earthly realm to the spiritual realm.

Nirvana is a visual summation of Kent’s understanding of the quintessential Buddhist belief in an eternal bliss achieved through detachment from earthly connections. The artist learned much about Eastern religious philosophy from his reading of Ananda Coomaraswamy’s (1877−1947) The Dance of Śiva: Fourteen Indian Essays (1918), which enlightened Kent during his sojourn in Alaska. This book by Coomaraswamy, a Ceylonese-American philosopher, metaphysician, art historian and curator of Indian Art at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, serves as a concise and accessible guide to Indian religious practice, particularly as it relates to the arts.

Nearly all of the paintings Kent executed in Vermont depict views of the mountainous landscape immediately visible from his Arlington studio. Situated adjacent to a bluff high on the slopes of Red Mountain the studio overlooked the Valley of Vermont to the south and Mt. Equinox to the north. However, in many of these paintings the landscape simply serves as a dramatic background for fictional narratives that cover a wide range of thematic content, enabling the artist to convey the full spectrum of human emotion without traveling more than a short hike from his studio.

Based upon a view looking southwest from Kent’s studio, the setting of The Trapper—with a haunting moon floating in the sky, the raking shadows of dusk, tree stumps smothered under a thick blanket of snow, and a bone-chillingly cool palette—creates a brooding atmosphere. A master at evoking mood via the landscape, Kent was equally adept at creating fictional narratives in his paintings that clarified his emotive intent, employing figures with which the viewer could identify. A trapper trudges through deep snow, carrying his trap and its bloody catch at his side, while his dog forges ahead. The artist would have had the opportunity to witness or hear about similar scenes of hunting and trapping in the wilderness surrounding Arlington. Yet, the seemingly minor hill depicted behind the trapper and his dog is in reality a precipitous drop, making the scene nearly impossible in the real world. Kent’s desire to convey a message of struggle and death is made all the more clear when one realizes that the narrative depicted in The Trapper is almost certainly a carefully wrought fiction.

Kent left Arlington after his divorce from Kathleen in 1925, but not without regret. This painting of Mt. Equinox can be understood as a nostalgic reminiscence by an artist looking back and fondly remembering his time spent in the Edenic setting of “Egypt.” Though begun in Vermont, Kent significantly altered Mt. Equinox, Summer at a later date, a habit the artist practiced with some regularity throughout his career. Close comparison with a black and white photograph found in the Kent archives at the Plattsburgh State Art Museum indicates that the artist started the painting in Vermont but subsequently repainted the foreground and mid-ground. The outline of the mountain in the photograph is identical to Mt. Equinox, Summer and passages of the earlier composition can still be seen in raking light, leaving no doubt that they are one and the same canvas. In reworking the canvas Kent substituted nude figures on horseback with a quintessentially Vermont scene: a deer stands alert before a scrim of white-barked birches with a cluster of white clad buildings, including a farmhouse and a church, tucked in the mid-ground at the base of Mt. Equinox.

Puritan Church is the only painting Kent executed in Vermont that depicts a scene not immediately visible from his studio. The Union Church is located in Sunderland, Vermont, in the valley a few miles east of Kent’s farm. Retitled Mother and Chicks before 1927, the painting’s two titles provide insight into Kent’s mindset and creative practice during his Vermont years. The painting’s original title, Puritan Church, brings to mind the Puritans’ strict beliefs relating to death and the afterlife—namely that only the “elect” will make it to Heaven. This association emphasizes the image’s dark, brooding atmosphere. Seen within this context, the gravestones that surround the church remind the viewer of man’s inevitable demise. The later title, Mother and Chicks, refers to the stately white-steepled church, the “Mother,” which looms protectively over the gaggle of gravestones, the “Chicks,” that are scattered around it. This humorous title not only lightens the overall mood of the picture but completely alters one’s understanding of the symbolism behind the painting’s subject matter. In this context the spirit-filled light that rains down on the scene conveys a feeling that death is not an end to be dreaded, but a transition to something greater. Taking both titles into consideration, Kent has taken a quintessential symbol of quaint rural New England life and turned it into an image that conveys the full range of human experience and emotions, from the tenderness of motherly love and the dark inevitability of death, to the ineffable spirituality of the deific, life-giving light that rains down on the scene from the heavens above.

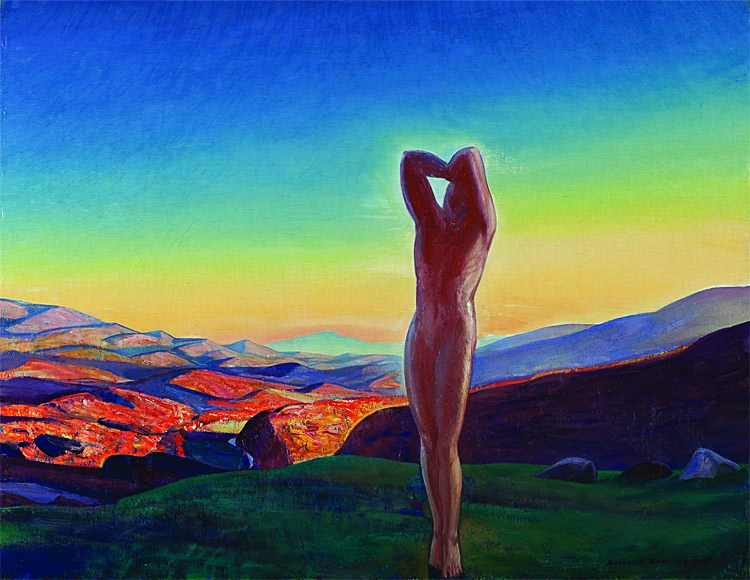

Autumn is an enigmatic, powerfully emotive painting. A solitary spectral nude—possibly a veiled self-portrait or a Nietszchean superman, but androgynous and ambiguous enough to be everyman or every woman—stands isolated in the shadowed foreground. Behind the figure a light-filled landscape of undulating mountains sings forth in an intense chromatic symphony. The sky graduates from a pink horizon surrounding a periwinkle Mt. Anthony (located twenty miles south of the artist’s Arlington studio, in Bennington, Vermont), through shades of golden yellow and cerulean blue to a canopy of intense navy blue. The autumnal foliage of the trees behind the figure seems to be exploding into flame, painted with thick, roughly textured brushstrokes in rich shades of red, orange and yellow, offset by deep purple shadows amongst the rolling hills. The scene is clearly based on the sublime southerly view from Kent’s studio, which the artist uses as a dramatic stage for a figure that conveys intensely felt emotions. It is impossible to tell if the specter is wailing in agony or basking in a state of spiritual ecstasy. This ambiguity, echoed by the painting’s liminal seasonal setting, is characteristic of Kent’s work from Vermont, as the artist attempts to convey the variety and complexity of the human condition. Begun during a period when Kent and his wife, Kathleen, were contemplating divorce and completed after they were no longer married, the painting may be expressive of both the artist’s anguish of loss and his sense of release at the attendant change this would engender in his life.

In 1934, Kent’s daughter Barbara married Alan Carter, the founding director of the Vermont Symphony Orchestra. Around the time of the Kent/Carter marriage, Kathleen Whiting Kent purchased a farm just outs ide of Woodstock, Vermont, in the small hamlet of Barnard. The early concerts of the fledgling Vermont Symphony Orchestra, featuring performances by Carter’s Cremona Quartet, were conducted in a barn on Kathleen Kent’s Barnard property. Rockwell Kent created an emblem, with an angel-like figure hovering in the sky playing the violin, for his son-in-law’s recently founded orchestra. Versions of the image appeared on programs for the symphony’s concerts and on the slip jacket for a record, Music in Vermont, released in 1967. This oil on panel version of the emblem depicts the figure hovering above a landscape featuring the south face of Mt. Equinox, based on the view from Kent’s former studio in Arlington.

During his last year in Vermont, Kent collaborated with his friend, the avant-garde composer Carl Ruggles, who had moved to Arlington the year before, to create a presentation copy of the first seven measures of Ruggles’ composition Portals. Dedicated to his patron, friend, and fellow artist, Harriette Bingham, Ruggles executed the dedicatory inscription at the top of the page in his passionate, slightly wavering penmanship. Kent was responsible for the penmanship of the title of the composition, “PORTALS,” executed in precise, chiseled Roman capitals, followed by an epigraph taken from a poem of the same title in Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

The concept of freedom was integral to the work of both Ruggles and Kent. Portals addresses a type of freedom advocated by Whitman—not simply freedom from worldly constraints, such as tradition or law, but an ultimate freedom from all physical bonds, a freedom that can only be attained through death. Portals conveys a feeling that death isn’t an end to be dreaded, but a transition to something greater. The birds in the drawing aren’t merely songbirds escaped from their cage. Kent employs them as a universal symbol of the human soul. In Portals death represents the ultimate freedom from this material world, wherein one’s soul can fly freely.

This article was associated with an exhibition at the Bennington Museum in the summer of 2012, Rockwell Kent's "Egypt" Shadow and Light in Vermont.

Jamie Franklin has served as curator for the Bennington Museum since 2005.

This article was originally published in the Summer 2012 issue of Antiques & Fine Art, a digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA magazine is affiliated with Incollect.com.

2. Alaska Paintings of Rockwell Kent (New York: M. Knoedler & Company, 1920).

3. Rockwell Kent to Ferdinand Howald, 24 August 1920, Ferdinand Howald Papers, Archives of American Art, Washington, DC, reel 955.