Seeing Takes Time: American Modernism at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

The first half of the twentieth century was filled with unprecedented social, technological, and cultural upheaval. Against this backdrop of change, traditional forms of artistic representation seemed inadequate. Many artists here and abroad pushed their work in new directions, embracing the revolutionary visual language of abstraction, while continuing to refer to the world around them. Bound to the past while heading into the future, they created what now is called Modernism.

In the early 1900s, Modernism was more than a movement or a style. It was a feeling, an outlook and, for some, a way of life influencing everything from fashion to politics. The exhibition Modern Times: American Art 1910–1950 focuses on work from the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art by artists who grappled during this period with what it meant to be Modern and what it was to be American. Some of these artists were born in the United States. Others were immigrants who became citizens. As a group, they made work in styles and of subjects as varied as they were. This pluralism was one of the hallmarks of Modernism in America. Because aesthetic strategies varied across the movement, the exhibition unfolds thematically in order to allow for aesthetic resonances and comparisons.

| Arthur Garfield Dove (1880–1946) Chinese Music, 1923 Oil and metallic paint on panel, 2111⁄16 x 18⅛ inches Philadelphia Museum of Art; The Alfred Stieglitz Collection (1949-18-2) “How hazardous it is to jump to the conclusion that what we don’t understand has no meaning.” Critic Arthur Jerome Eddy wrote this sentiment in a 1914 essay comparing the shock of some modern art to the unfamiliar sounds of Chinese music, which may have inspired this painting’s title. Dove appears to have taken this public defense of abstract art as the point of departure for a dynamic composition. The subjective association of sound and color, known as synesthesia, was popular within the Stieglitz circle. Although parts of the composition look like industrial buildings and circular saw blades, Dove intended these shapes to convey intangible rhythms and forces from the world around him; this painting used a pictorial vocabulary of abstract form that would sustain the artist over the next two decades. The picture was one of only three works by Dove that Stieglitz chose to be included in the Société Anonyme’s landmark International Exhibition of Modern Art, held at the Brooklyn Museum in 1926. |  |

| Florine Stettheimer (1871–1944) Spring Sale at Bendel’s, 1921 Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 inches Philadelphia Museum of Art; Gift of Miss Ettie Stettheimer (1951-27-1) The boisterous vitality of American leisure activities fascinated Florine Stettheimer, who portrayed them with an evident sense of humor. Here, Stettheimer offers a glimpse into the lively world of high fashion at discounted prices. Imagine elegantly dressed women twisting, preening, and diving for bargains in a posh department store, as we see in the painting, which features her typical jewel-like palette of bright reds, oranges, yellows, greens, and pinks. Henri Bendel opened his luxurious New York store on Fifth Avenue in 1913. Stettheimer was among the upper class that may have shopped there. Along with her sisters and her mother, Stettheimer hosted an elite salon that attracted many of the leading talents of her day, such as Charles Demuth, Marcel Duchamp, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Alfred Stieglitz, whose work is included in the exhibition. |

| Georgia O’Keeffe (1887 – 1986) Red and Orange Streak, 1919 Oil on canvas, 27 x 23 inches Philadelphia Museum of Art; Bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe for the Alfred Stieglitz Collection (1987-70-3) Georgia O’Keeffe blurred distinctions between depictions of the observable natural world and interpretations of its intangible qualities. Here, a vibrant arc of colors cuts across a dark background, intersecting a glowing red horizon. This horizontal band, the symbol of a traditional landscape, recedes behind O’Keeffe’s vivid artistic gesture. She made Red and Orange Streak in New York, months after she left the sweeping landscapes of Texas that inspired the painting. O’Keeffe was mesmerized by the wide-open plains of Texas, especially at night when she would take long walks alone. Enveloped in darkness, the disembodied sounds of train whistles and lowing cattle suggested shapes and colors to the artist. She was also fascinated by the storms that made their way across the flat Texas landscape, sending streaks of lightning down to the earth. Red and Orange Streak conveys her memories and feelings about the place—a mood rather than a factual description. She transformed the remembered landscape into something uniquely her own. |  |

“Nobody sees a flower—really—it is so small— we haven’t time—and to see takes time.” |

— Georgia O’Keeffe 1 |

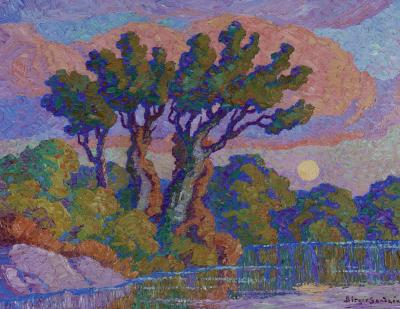

| Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) From the Lake No. 3, 1924 Oil on canvas, 36 x 30 inches Philadelphia Museum of Art; Bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe for the Alfred Stieglitz Collection (1987-70-2) After moving to New York in 1918, Georgia O’Keeffe began spending summers at Alfred Stieglitz’s family home on Lake George in upstate New York. From the Lake No. 3 is one of her most abstract paintings inspired by those surroundings. Abandoning traditional landscape elements such as the flat surface of the lake or a clear horizon, she embraced the colors in the earth, water, trees, and sky, evoking a sense of the place without depicting its literal qualities. |

|

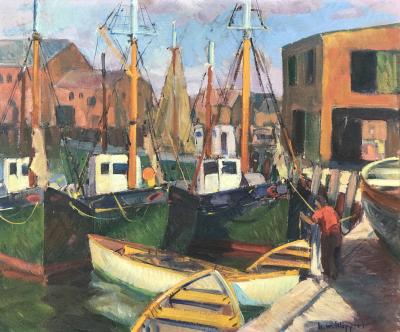

| Charles Sheeler (1883–1965) Pertaining to Yachts and Yachting, 1922 Oil on canvas, 20 x 24 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art; Bequest of Margaretta S. Hinchman (1955-96-9) |

| Charles Sheeler made several works on the subject of sailing, interpreting the tradition of nautical painting through his own Modern style. A proponent of Precisionism, Sheeler reduced his compositions to streamlined geometric elements, hinting at his subject matter through shapes, lines, and color. Here, he creates the visual essence of a yachting scene, whether for pleasure or competition is unknown. The imagery is emphasized in the vessels’ billowing sails, which cut crisp arcs across the composition. The sails create a repeating pattern, as though they were filled with air. They also appear to merge with the sky, making a connection to the winds that propel the boats through the waves. |

| Alice Neel (American, 1900 – 1984) Portrait of John with Hat, 1935 Oil on canvas, 23½ x 21½ inches Philadelphia Museum of Art; Gift of the estate of Arthur M. Bullowa (1993-119-2) Alice Neel met John Rothschild (1900–1975) in 1932. She stayed with him in 1934 after her lover Kenneth Doolittle slashed and burned many of her paintings and drawings at the apartment that they shared. Rothschild helped Neel acquire a small cottage in Spring Lake, New Jersey, a seaside town where she spent time each summer for the rest of her life. This portrait shows her friend’s strong jaw and distinctive profile clearly outlined against the ocean behind him. |  |

.jpg) | Charles Demuth (1883 – 1935) Lancaster (In the Province No. 2), 1920 Oil on canvas, 30 x 16 inches Philadelphia Museum of Art; The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection (1950-134-45) Over the course of his career, Charles Demuth lived and worked in New York, Philadelphia, Provincetown, and Paris, but his real home was in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, which he referred to as “the province.” The city provided the subject for many of his architectural compositions such as this water tower and cupola of an industrial building from the 1800s not far from his family’s house. Demuth used sharp lines and clearly defined patches of color to divide the structures, and even the sky, into precise geometric shapes in a style that came to be described as Precisionism. |

|

| Horace Pippin (1888 – 1946) The Getaway, 1939 Oil on canvas, 24⅝ x 36 inches Philadelphia Museum of Art; Bequest of Daniel W. Dietrich II (2016-3-3) |

| While serving in World War I, Horace Pippin sustained a serious injury to his right arm. Several years later, despite his disability, he taught himself to paint. He went on to become one of the most successful and respected African American artists of his day. In The Getaway, Pippin painted a solitary red fox running with a bird in its mouth. A golden moon hovers on the horizon. Its yellow light reflects onto the clouds, illuminating them against the dark, night sky. Looking at the back of the painting reveals that Pippin began the composition as a daytime scene with blue skies, red barns, and fox standing still in the snow. Art historian Anne Monahan suggests that Pippin may have seen Winslow Homer’s Fox Hunt at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, after which Pippin perhaps altered his own composition, inspired by Homer’s scene. However, there are key differences between the two. In Homer’s painting, the fox is under attack by crows and faring badly; in Pippin’s composition, the predator wins the day. |

While the museum has hosted many exhibitions that have included modern American art, this is the first major display to focus on this aspect of its own collection. At the heart of the project are paintings from the estate of the famous gallerist and photographer Alfred Stieglitz given to the Museum of Georgia O’Keeffe in 1949. The conversation is broadened with work by African American artists, women in addition to O’Keeffe, artists from Philadelphia, and modernists working in a variety of media that help show the breadth of the collection, the diversity of the movement, and the beautiful chaos of innovation that made this period so dynamic and influential. This framing provides an opportunity to see the collection from the perspective of the twenty-first century, because seeing takes time.

Modern Times: American Art 1910–1950 is on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from April 12–September 3, 2018. For information, call 215.235.0050 or visit www.philamuseum.org.

Jessica Smith is curator of American Art and Manager for the Center of American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art. She is curator for Modern Times: American Art 1910–1950.

This article was originally published in our Summer 2018 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.