|

The seemingly effortless combination of modern sculpture and design with folk and decorative arts is the result of decades of researching, locating, and acquiring material that speaks to the aesthetic similarities of work separated only by time.

Folk portraits hang on the fireplace wall. Seen in the dining room in the distance is a set of Ward Bennett chairs around a George Tanier table from the 1950s–1960s, behind which is a rare full-length pastel of a girl in a yellow dress. A pair of 1960s leather chairs by Kurt Thut center a chrome table, probably Knoll, of the same vintage. Behind them is a grisaille interior painting of a staircase by Lowell Blair Nesbitt (1933–1993), which the couple purchased in 1968. “We met Nesbitt at a party hosted on his behalf by collectors. We were not previously familiar with his work,” says Vera. She adds, “The next day we purchased this painting, even though we didn’t have room to hang it. It remained on the floor for another six months, when we moved to a larger apartment.” Jokes Pepi, “That shows the suspect sanity mindset of true collectors. If you love it, buy it, and figure things out later.”

The marble head is from David Wheatcroft’s private collection; though it’s by an unknown artist, it reminds Vera of work by William Zorach. Embrace, on the other side, is signed “TB” or “BT,” and is from Jackie Sideli. It reminds Vera of a Brâncuși.

|

"S

he’s what folk art is all about,” says Pepi Jelinek. He’s referring to a portrait that hangs in his home.1 Depicted with a form more abstract than clearly delineated, leaning slightly to one side, with hands unnaturally oversized, the female sitter was evidently painted by an artist who had not received professional training. Not only is the naïve manner in which she is portrayed appealing, but her simply painted features are entrancing, her gaze conveying intelligence and strength of character. It’s as if she’s pondering a question, or considering whether the viewer is worthy of an answer. While the stylistic elements of the painting are emblematic of folk art, and the portrait is clearly from the nineteenth century, her visage and form share a connection with modern art; her portrait seems just slightly removed from the work of Modigliani.

The natural association between folk and modern art has been at the heart of an upswing in scholarship and museum exhibitions focusing on the influence of folk art on artists working in America in the early- to mid-decades of the twentieth century. Some of the early modernist artists and sculptors who collected folk art, such as Elie and Viola Nadelman, Robert Laurent, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and William and Marguerite Zorach, appreciated the pure, abstract forms that related to their own artistic expression. New York City modern art dealer Edith Gregor Halpert was also instrumental in bringing awareness to folk art as an art form, offering it for sale in her Downtown Gallery to influential collectors such as Abby Aldrich Rockefeller.

|

This couple, painted by Ammi Phillips (1788–1865), circa 1815, date from the artist’s early period (the Border period); their names are not known. Pepi and Vera have not always been successful in acquiring pairs of portraits at the same time. Initially, only the portrait of the woman was available. They wanted a pair, however, and three years later they were pleased to find a husband and wife from Phillips’ later period (to the left of the mantel), which they acquired. But, as luck would have it, the same week the mate to their single portrait came on the market. Knowing this might be their only chance, they hastily sold a number of paintings, samplers, weathervanes, a Belknap, and another Phillips in order to make the purchase. Placed beneath the pair is a Zuni pot, circa 1910, and mid-century wooden sculptures that were likely used in a storefront.

|

|

Pepi and Vera acquired this circa-1830 pair of portraits by Ammi Phillips at auction the same week the portrait of the husband, now on the opposite side of the mantel, became available. The deer weathervane was recently purchased from Olde Hope Antiques, in front of which is a contemporary turned bowl. The carving of a soldier is from Judith and James Milne.

|

|  |

| “We purchased this portrait on the phone while in a taxi on our way to the airport,” recalls Pepi. “We weren’t sure at the time if she was even American, but we didn’t want to lose her, so upped our bid, which we don’t often do.” After researching the portrait, they learned it was indeed American and had been deaccessioned from the Art Institute of Chicago, possibly because the artist was unknown. It has been illustrated in books by James Thomas Flexner and Alice Ford. To the right, is a statue by Archipenko (1887–1964), dated 1914, and a Picasso vase; to the left, is a bronze head by Elie Nadelman (1882–1846).

|

The visual associations evident in this collection between folk and modern art flow seamlessly through and within each room. For the past fifty-plus years, Pepi and his wife, Vera, have combined “old” and “new,” not as a decorative statement, but organically and naturally. As longtime friend and folk art expert Nancy Druckman has said of the couple and their collection, “They were prescient in mixing the old with modern art, lovingly and thoughtfully acquired.”

The couple’s aesthetic connection with a number of twentieth-century folk art collectors extends to their shared European roots. Some of the earliest collectors and curators of the material, including Halpert, the Nadelmans, Holger Cahill, and Maxim Karolik, were European émigrés. Both Pepi and Vera were born in Czechoslovakia; he left for England in 1939 as a child with his family, before moving to America twenty years later, and she, less fortunate, only arrived in the United States shortly after WWII. As a married couple in the early 1960s, they would return overseas for travel and study, a tradition they continue to this day.

Art was already a shared interest when they married, and it was in Europe that the couple began collecting. The first work they acquired was an impressionist painting while in Yugoslavia. Both abroad and in the States, they visited museums, shows, and auctions that were featuring primarily European material. Though initially drawn to landscapes, their interests migrated to portraits, particularly early Flemish portraits and early twentieth-century masters. Such art was, however, beyond their financial means. It was on a trip to Switzerland in the late 1960s, with toddlers in tow, that they attended an international exhibition of naïve art. They were attracted specifically to the flat, abstract quality of the material, which reminded them of the modern art they adored. It was at that point they knew their focus would be on collecting folk art.

|

In 1973, the couple made a failed bid on a portrait by the artist who painted the group of three hanging on the wall. A couple of years later, the portraits of the husband and wife, shown here, were offered at Weschler’s Auctioneers in Washington, D.C. Pepi and Vera recognized the artist and acquired the portraits. Vera later found the portrait of the child at Sotheby’s; the child became the pair’s “adopted” daughter (given the child’s similarity to the couple, she may well have been their actual daughter). Pepi was so enthralled with work by this artist that he undertook research to identify him. He and Vera know of more than fifty portraits by the hand of the artist, Ralph D. Curtis (1808–1885). The portraits complement the modern furniture in the room. A pastel by Ruth Bascom (1772–1848) that hangs beside a rooster weathervane, from James Kilvington, and the “Rochester” horse is from Judith and James Milne. Together they center Native American baskets.

|

|

|  |

The Ashahel Powers (1813–1843) painting of an unknown woman in an easy chair was from the Bert and Nina Fletcher Little collection. The artist used a similar curtain treatment for his portrait of Eliza Ann Farrar at the Springfield Art and Historical Society, Massachusetts. The painted apothecary box was purchased in Italy. Says Pepi, “When Vera bought this for me, she asked the shopkeeper if it was antique. She was promptly told, ‘Of course not, it’s only two hundred years old.’” Laughs Pepi, “Antique in Italy, of course, refers to Roman times.” The box sits on a decorated chest that has the initials “J” and “S,” and is probably from the Midwest.

|

| A painting of a child by Zedekiah Belknap (1781–1858) is placed above an elaborate paint-decorated lift-top chest that the couple purchased at the Winter Antiques Show. The carved figure is from Harvey Kahn’s collection, and was probably a storefront mannequin.

|

|

Pepi has long been drawn to frakturs, noting “Frakturs were the last example of illuminated manuscript writing as expressed by a particular ethnic group; this is real folk art.” He adds, “What excites me is the exuberance of the artwork, often in stark contrast to what’s written, which is usually more somber.” The couple’s first fraktur was the flying angel (top row, second from left). Their favorite is by Spannenberg, the Easton Bible Artist, (third from the left in the middle row).

|

|

|  |

A carved trade sign of a pocket watch hangs above a Samuel Benz fraktur, below which is a recent acquisition of an imagined cityscape by Abraham Heebner (1797–1868). In addition, there are other frakturs, including one by Henry Young, and a depiction of Swiss soldiers by Dors Rudy.

|

| A watercolor of a husband and wife by Joseph Davis (1811–1865) hangs above a watercolor, also of a husband and wife, by “Dupue,” an artist possibly from North Carolina. The oil portrait of an unknown sitter is attributed to William Kennedy (1818–after 1880), a member of the Prior-Hamblen group.

|

|

|  |

Vera was helping with preview bags at The American Antiques Show (TAAS) a number of years ago when she noticed this circa-1840 pair advertised in the catalogue. Once the show opened she rushed into Ricco Maresca’s booth and purchased the pair without knowing anything about them. They have many features associated with modern artists; the wife’s portrait, in particular, shares characteristics with work by Modigliani. The portrait of the wife is referenced in the opening paragraph.

|

|

|

This portrait is one of a group of five, consisting of a couple, two children, and this portrait of “Mrs. Fish,” which was separated from the others prior to its entering the couple’s collection. Pepi describes Mrs. Fish’s expression as “almost religious in character.” Pepi is currently researching the artist, based on a signed example in the collection of a friend.

|

|

When they returned from their trip, they couldn’t wait to begin acquiring art and started with two twentieth-century naïve paintings (which they’ve since upgraded). Other purchases followed, and, when in 1970 they acquired a country house, they began attending local auctions and noticing the Americana they would soon start to collect. Though they shared a European heritage, they were drawn to the modernist qualities of nineteenth-century American folk art. Shortly thereafter, in 1973, Pepi and Vera attended an auction that took them to a new level of collecting; every major dealer was there to bid on the material. The two dove in and purchased a bread bowl and a pencil-and-ink farm scene by Fritz Vogt (1842–1900). They proved to have an excellent sense for quality even at this early stage of collecting; years later the Vogt was shown at the Fenimore Art Museum in an exhibition of the artist’s work and was chosen for the exhibition poster (its mate is at the Albany Historical Society). They were also interested in a portrait of a woman seated in a high-back chair. “We planned to spend $1,100,” says Vera, “which was a stretch for us.” It sold for $9,000, to a dealer. They would eventually acquire several portraits by the same artist, and Pepi would write an article identifying him as Ralph D. Curtis.2

The couple began collecting in earnest later that year at the Sotheby’s sale of Edith Halpert’s collection of folk art. The catalogue had come out while Vera was in Italy studying for her Ph.D. “When I returned through JFK Airport,” she says, “I was greeted with Pepi waving the catalogue in the air!” Says Pepi, “The estimates were so high we didn’t even examine many of the items carefully.” On the day of the auction, however, they realized that the selling prices were lower than the estimates. They purchased their first mourning picture, a theorem painting, and a fraktur. “We were shaking in our boots because we hadn’t examined them,” says Vera. They were relieved when the person sitting in front of them, collector Joan Johnson, turned around and told them they’d done well. “We still have these works,” Vera confirms.

|

The owners have acquired a number of quilts through the years, many of which are stored in painted chests. On the bed is a Baltimore Album quilt, which the couple hopes to research; in the center of the quilt is the name “Herbert B. T. Harris” and other initials are scattered throughout. A Jens Risom chair provides support for another quilt. On the wall are two theorem paintings; the one on the left is from the Lititz Moravian Girls’ School, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. The oil portrait of a young lady is signed by William Matthew Prior (1806–1873). The Thomas Chambers’ landscape is one of only three similar scenes known. On the far wall is a portrait by Samuel and Ruth Shute; it was from the Garbish sale. Below the Shute are milliners’ heads.

|

|

|  |

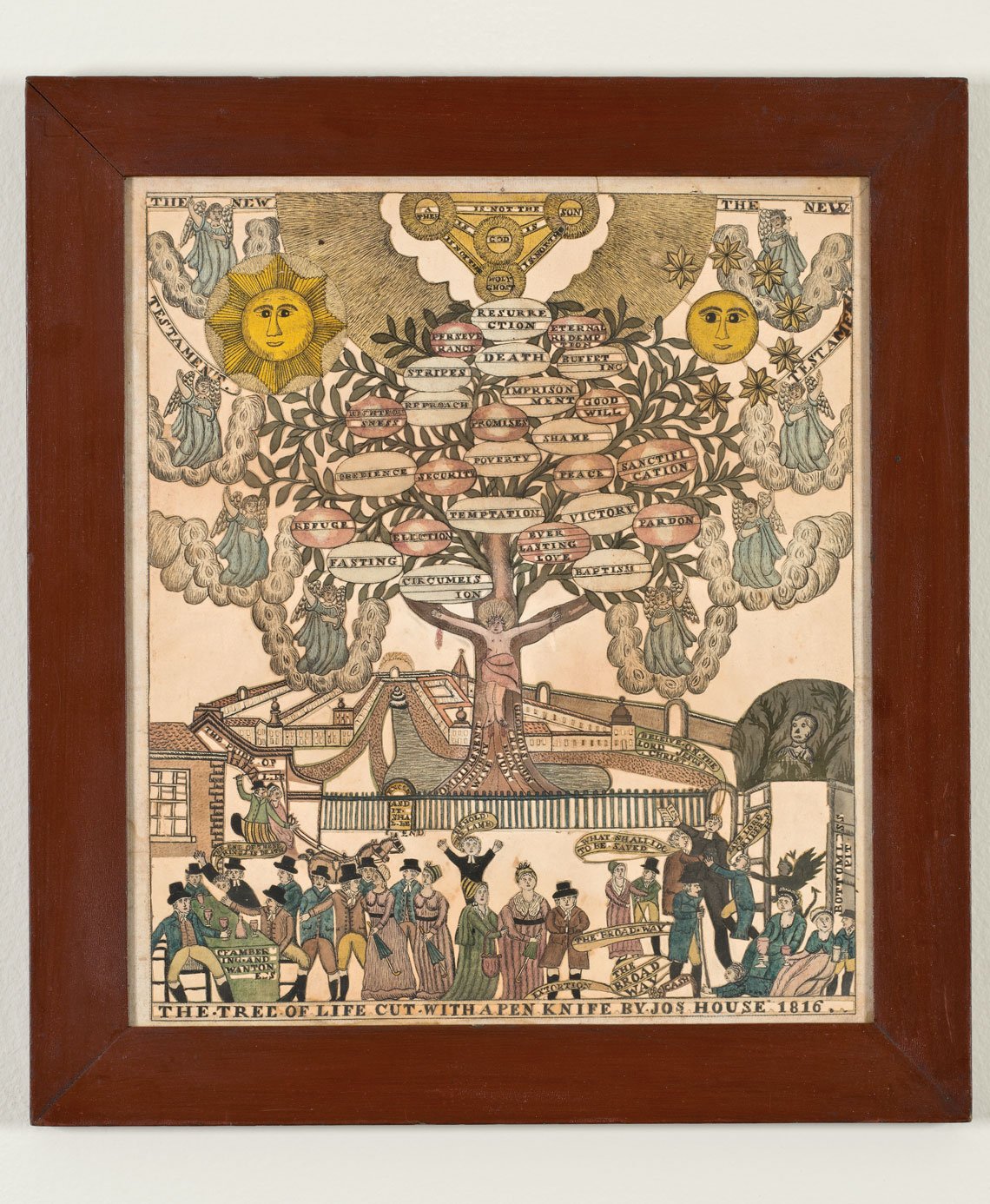

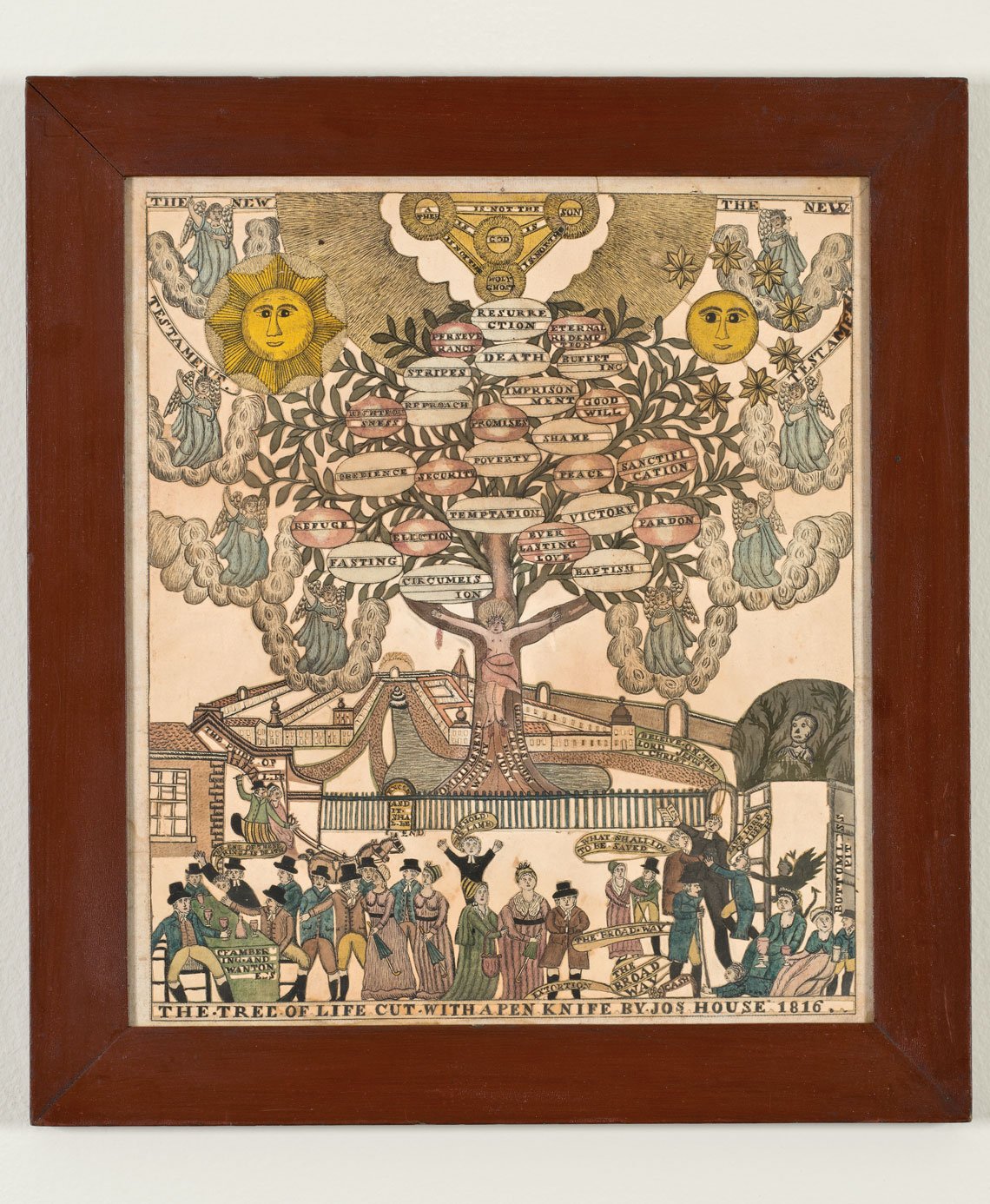

This charming pen-and-ink drawing, embellished with watercolor is from Hartford, Connecticut. The maker identified the scene and his name along the bottom: “Tree of Life cut with a penknife by Joseph House, 1816.”

|

| This portrait of Anna Jocelin, 1823-1824, is by Micah Williams, one of Pepi’s favorite painters. He thinks of Williams as the “pastelist Ammi Phillips.”

|

|  |

| Theorem on velvet by Susan Shaw. Part of the Halpert sale, 1973. One of the rare signed theorems.

|

As she reflects on their collecting through the years, Vera notes, “In the beginning we were mostly interested in two-dimensional things, such as portraits, theorems, mourning pictures, and fraktur. Though I didn’t favor them at first, I’ve come to love sculpture and weathervanes.” She adds, “We grew into them.” Vera believes that a collection doesn’t need to contain works by big name artists as long as the forms are appealing. For instance, a sculpture titled Embrace, by an unknown carver, looks like a Brâncuşi, and a carved marble head in the same room reminds her of work by William Zorach.

In the purchase of paintings, the couple has always been in agreement. Pepi or Vera may have slight individual preferences, but they have very similar tastes, which, they say, is very useful. Next on their list? “We would aspire to have some more paintings,” they say. “Specifically a Brewster, a Peck, and a young sitter by Shute that’s as good, or better, than what we currently have.” As with many seasoned collectors, Pepi and Vera comment on the importance of relationships with fellow collectors, dealers, and auctioneers. As to shared interests with other collectors? The French avant-gardist and collector Jean Cocteau, was once asked the question all collectors are asked: “If there was a fire and you could only take one thing, what would it be?” He replied, “I would take the fire.” Pepi concurs.

|

|  |

This portrait of a woman with a proud bearing , attributed to Susanna Paine, was offered at Antiques in Manchester (New Hampshire) a few years ago. “Though we had plenty of portraits at the time,” says Vera, “I couldn’t get her out of my head. I called the dealer a year later and she still had the portrait so we bought it.” She adds, “I love her.” The painted chest was one of the first pieces of furniture the couple purchased; it is from Lebanon, Pennsylvania.

|

| This striking portrait was owned by Peter Tillou, and exhibited in a show of his collection, Nineteenth-Century Folk Painting: Our Spirited National Heritage, in Cooperstown (1973). Says Vera, “When we saw her for the first time, we flipped because she looked so contemporary. When Peter sold the collection in the 1980s, she came up for auction, and we purchased her. She was supposedly owned by Elie Nadelman.”

|

Pepi and Vera have assembled a remarkable, harmonious collection. As Nancy Druckman recently noted, “They are true collectors and have spent a lifetime studying and loving the material.” As evidenced when the couple are focused on an object or artwork, their faces are lit with an intelligent delight that conveys their genuine passion and appreciation for what is before them.

This article was originally published in the Autumn 2017 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.

Additional Images

|

|  |

The couple has recently started to collect portrait miniatures. Middle upper and center: Mrs. Moses Russell; bottom by J. H. Gillespie; others by anonymous artists.

|

| Fraktur by William Murray. Gates family, New York, 1820 watercolor.

|

|

|  |

Portrait of a woman attributed to J. A. Davis, 1830-40. Collection of Jean Lipman.

|

| This watercolor of a woman is by Emily Eastman (b. 1804). The stylized hair and lace is modern in appearance, though the work dates to the mid to late nineteenth century.

|

|

The Doctor’s House, Searsport, Maine, circa 1835. Acquired from Peter Baker. Pepi says he was drawn to the outlandish perspective.

|

|

This watercolor, identified as Prospect of the U.S. Garrison at Lawrenceville near Pittsburgh, is by an unknown hand.

|

|

|  |

One of two watercolors by Jacob Maentel (1763–1863). In its depiction of tiny feet and oversized attire, this work is typical of the artist.

|

| This portrait of Henry Allen Pease, by Erastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900), was in the Stuart Gregory auction in 1979. Pepi and Vera were unable to acquire it at the time. Field’s portrait of Deacon Harlow Pease, the father of Henry Allen, is in a private collection. Field also painted the decorative frame.

|

|

|  |

This watercolor mourning picture, from Philadelphia collector Dick Cantor’s collection, is exceedingly detailed, with strong colors that have not faded.

|

| This 1818 mourning picture from Rhode Island memorializes three people. It is unusual in that the spirit of one of the deceased (Lydia Wilkinson) is making a getaway—even startling the church, which leans to one side. From Barbara Pollack.

|

|

|  |

Residence of David Lambert of Brookman’s Corners, NY, Oct. 23, 1895, Fritz Vogt. Pencil and crayon. One of three Vogt’s in collection.

|

| The delicacy with which this still life is painted is extraordinary. It is related to the style of Emma Cady and signed, “Adeleta Enretty [?], Professor of Painting.”

|

1. Shown on page 82, upper right.

2. J. E. Jelinek, “Ralph D. Curtis: A Nineteenth-Century Folk Artist Identified,” in The Magazine Antiques 176, no. 5 (November 2009).